Today (April 18, 2024), the Australian Bureau of Statistics released the latest - Labour Force,…

Australian labour market data – mostly discouraging

Today the ABS released the Labour Force data for May 2010 which show that the unemployment rate has fallen by 0.2 percentage points ostensibly, if you believe the press reports and the comments from the bank economists, on the back of continued strong growth in full-time employment. The truth is different. While full-time employment growth was positive it is not accelerating and overall employment growth slowed in May 2010. More importantly, all the fall in unemployment was due to a further drop in the labour force participation rate. So employment growth remains sluggish and is barely keeping pace with the growth in the population. The good news is that aggregate hours worked continued to increase which is reducing underemployment a little. While the bank economists have hailed today’s figures as indicative of an economy “near full capacity”, the reality is that the data is consistent with a broad array of statistics showing the Australian economy is slowing as the effects of the fiscal stimulus dissipate and and private spending remains subdued. It is amazing how a few headlines can distort what is actually going on.

The summary ABS Labour Force results for May 2010 are (seasonally adjusted):

- Employment increased 26,900 (+0.2 per cent) with full-time employment increasing by 36,400 and being partially offset by a reduction of 9,400 in part-time employment.

- Unemployment decreased 25,400 (-4.1 per cent) to 600,900.

- The official unemployment rate fell 0.2 percentage points to 5.2 per cent.

- The participation rate fell by 0.2 percentage points remained at 65.1 per cent which helped bring the unemployment rate down. Participation is still well down from its most recent peak (April 2008) of 65.6 per cent. So the approximate number of workers that have dropped out of the labour force because of diminishing job prospects (that is, the rise in hidden unemployed) is 96 thousand persons.

- Aggregate monthly hours worked increased 43.9 million hours(+2.9 per cent) and have now exceeded the July 2008 peak from the last cycle.

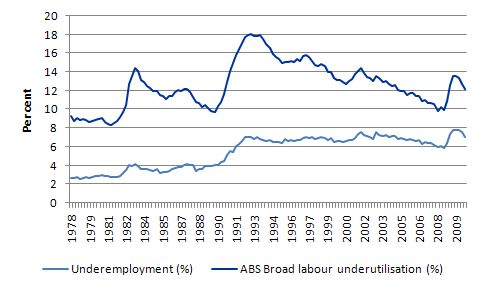

- Total labour underutilisation (the sum of underemployment and unemployment) is down to 12.2 per cent from the February quarter value of 12.8 per cent. The drop is made largely due to a fall in underemployment (from 7.5 per cent to 7.0 per cent) which isn’t surprising given the recovery in working hours. The reality is that when you combine the participation rate effects (hidden unemployment) with the ABS broad labour underutilisation you still have around 13.2 per cent of workers without enough work. That is significant evidence of labour market slack despite the rhetoric that we are approaching full capacity.

This is how today’s data was reported on the ABC news – Full-time work leads unemployment fall. That sounds good. The report said:

Hiring not firing: Unemployment fell to 5.2 per cent in May … Australia’s labour market has surprised analysts again, with unemployment falling to 5.2 per cent in May.

A small fall in the proportion of people looking for work from 65.2 to 65.1 per cent combined with the increase in jobs to lead unemployment down from 5.4 per cent in April to 5.2 per cent in May.

As the analysis that follows will show the actual fact is that the growth in employment barely kept paced with population growth and the drop in unemployment (and its rate) was all down to the fall in the participation rate. Further, employment growth actually slowed this month.

When you combine those facts you will see how misleading the news headline (above) is.

ABS News also recorded the comments from the bank economists. So:

It’s a very strong report with that rise in employment solely driven by full-time employment … “We saw a big rise in the number of hours worked and a significant drop in the unemployment rate so all round a pretty positive report.

[AND]

Not only are employees holding onto and finding new jobs, but existing workers have got back the bulk of the hours they lost in the GFC

[AND]

We do think the RBA will sit on the sidelines for the time being, that said we are expecting another two rate hikes by year end.

So the bank economists are predicting further interest rate rises on the back of a weakening labour market! That about says it all.

The Sydney Morning Herald story on the data release carried the headlines Jobless rate falls , which again presents a positive take on things.

They quoted the Prime Minister who said “We now have about half the unemployment level of the United States, half the unemployment rate of many countries in Europe”, which is a fairly inaccurate statement. Not only does this assessment fail to take into account the participation effects I will discuss presently but the broad labour underutilisation rate (unemployment and underemployment) in Australia was reported today to be 12.2 per cent and if you add about 1 per cent for hidden unemployment you get 13.2 per cent. The comparable US figure is around 16.8 per cent. That more correct comparison puts things in different light.

Employment growth slowing but positive

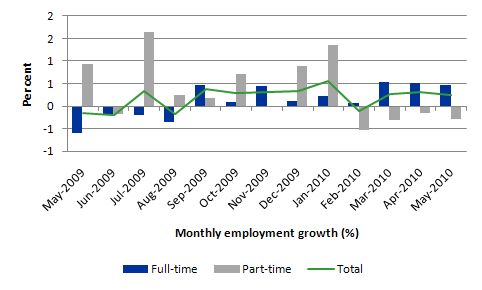

The following graph shows the month by month growth in full-time (blue columns), part-time (grey columns) and total employment (green line) over the last 12 months to May 2010 ysing seasonally adjusted data The overall picture is mildly positive. The sample period covers the latter parts of the downturn (May 2009 to August 2009) as full time employment growth was negative and part-time growth was mostly positive, which kept a lid on the overall employment losses although the slack showed up in lost hours of work, which was a notable feature of the downturn.

By September 2009, the effects of the fiscal stimulus package introduced in February 2009 were now evident and employment growth started to pick up quickly with growth in full-time employment signalling renewed optimism. In the more recent period, full-time employment growth continues to be positive but is slowing as part-time employment continues to fall.

While employment growth remains positive it has slowed in the last month. It is clear that the impacts of the fiscal stimulus, which drove GDP growth in the March quarter (see Australia GDP growth flat-lining) are now dissipating and private spending is not yet strong enough to really push the labour market to the next level of recovery.

So the picture is far from rosy although the additional full-time work is pushing total working hours up.

Unemployment trends

The official data shows that unemployment fell by 25,400 (-4.1 per cent) to 600,900 and the official unemployment rate fell 0.2 percentage points to 5.2 per cent. This is being hailed as a wonderful result and indicative of the underlying strength of the Australian economy. Standby for politicians to start saying we are close to full employment as a result of this month’s data.

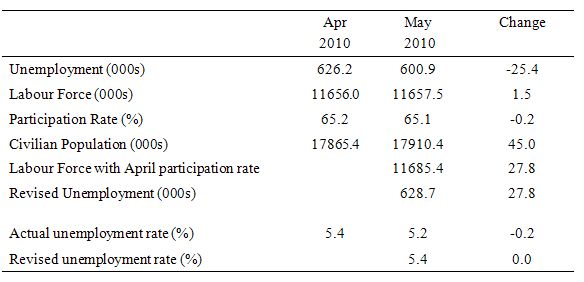

Well nothing could be further from the truth. The following Table shows you what is really going on. It calculates the impact on the labour force and unemployment of the drop in the participation rate (down 0.2 percentage points). First, I computed the civilian population (by dividing the labour force by the participation rate).

Second, I computed the Labour Force with April participation rate by multiplying the Civilian Population estimate in May 2010 by the higher April participation rate. So given growth in the underlying population, if the participation rate had not dropped the labour force would have been 27.8 thousand workers larger in May 2010 than the official estimate. Most of those extra workers entered the ranks of the hidden unemployed.

Third, I revised the unemployment rate estimate by adding the 27.8 thousand workers to the May pool of official unemployment (600.9 thousand) and expressed the new higher estimated pool as a percentage of the upwardly revised Labour Force. The revised estimate of the unemployment rate is now 5.4 per cent for May 2010 which is unchanged from the official April 2010 estimate.

Conclusion: Almost all the fall in official unemployment and the unemployment rate was due to the participation rate contraction. This is not an improvement at all. It is just shifting the unemployed from the official side of the line (in the Labour Force) to the unofficial (hidden) side of the line (Not in the Labour Force).

You just cannot conclude that the economy is robust when you simultaneously have slowing employment growth and declining participation.

So how much difference has these participation effects made over the course of the downturn? The peak participation rate in the recent period has been in April 2008 (65.6 per cent). The participation rate is currently at 65.1 per cent. I simulated what the unemployment rate would have been if the participation rate since April 2008 was constant at that peak value.

The following graph shows the results. The blue line is the participation rate-adjusted unemployment rate (%) and the green line is the official unemployment rate. The difference between the lines is the participation rate effect on the labour force (and hence unemployment) as the participation rate fell below its peak. It indicates the hidden unemployment rate since April 2008.

While the official unemployment rate is estimated to be 5.2 per cent in May 2010 and everyone is crowing happily about that, the participation rate-adjusted unemployment rate would be 5.9 per cent. Quite a different story indeed.

Broader labour underutilisation

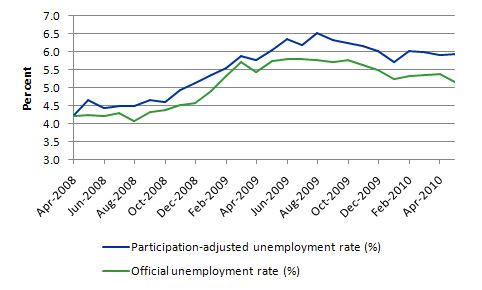

The following graph shows the movement since February 1978 to May 2010 (quarterly data) in the ABS Broad Labour Underutilisation rate (dark blue line) and their measure of underemployment (light blue line). The difference between the lines is the unemployment rate.

First, you can see the steady rise in underemployment as the economy grew after the 1991 recession. The economy was increasingly reducing unemployment by the creation of part-time work which still rationed the hours available relative to the preferences of the workers (who wanted more). The fact that total underutilisation didn’t scale the heights reached at the peak of the 1991 recession is due to the relatively small rise in the unemployment rate this time.

As you can see underemployment rose more sharply in the current downturn than it did in the 1982 and 1991 recessions. Almost all the labour slack in the 1982 recession was associated with rising unemployment. Underemployment didn’t really become a major issue until the 1991 recession.

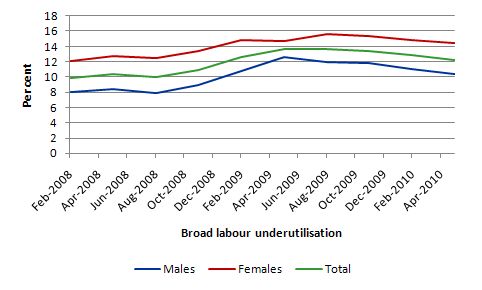

The following graph shows the movements in the ABS Broad Labour Underutilisation rate measure since the beginning of the downturn (February quarter 2008) for males (blue line), females (green line), and total (red line). Typically, females have been the victims of the hours rationing due to their over-representation in the service sector. A notable feature of the current downturn is that underemployment has broadened its impact to embrace males. You

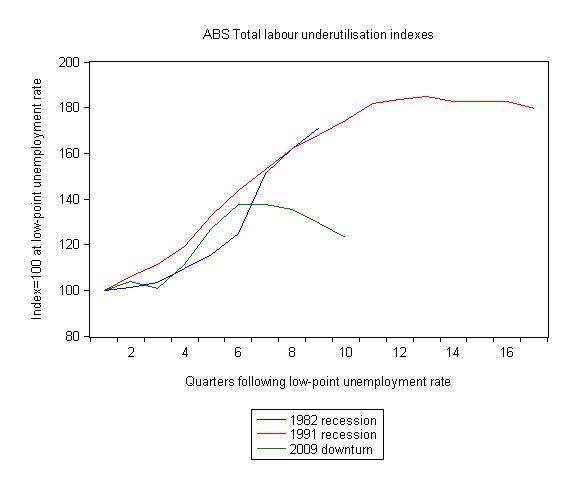

The following graph my 3-recessions graph for broad labour underutilisation (as measured by the ABS). It compares how quickly the broad labour underutilisation rose in Australia in the 1991 recession and the current episode. The broad labour underutilisation was indexed at 100 at its lowest rate before the recession in each case (June 1981; November 1989; February 2008, respectively) and then indexed to that base for each of the quarters until it peaked. It provides a graphical depiction of the speed at which the recession unfolded (which tells you something about each episode) and the length of time that the labour market deteriorated (expressed in terms of the unemployment rate).

The different behaviour in the current downturn is now starkly contrasted to the way the last two major recessions unfolded. You can clearly appreciate how harsh the protracted meltdown in 1991 actually was.

Hours worked – the good news

While total hours worked in April fell by 8.3 million hours (-0.5 per cent) which was on top of a fall in March of 10 million hours (-0.6 per cent), there was a sharp rebound in May – Aggregate monthly hours worked increased 43.9 million hours(+2.9 per cent).If the May figure was weak I was prepared to conclude that the trend would be weakening but the positive trend is now well-defined which is good news.

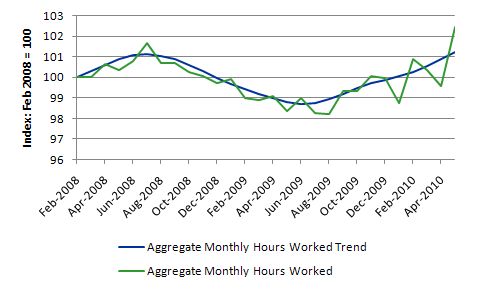

The following graph is taken from the the ABS data and shows the trend and seasonally adjusted aggregate hours worked indexed to 100 at the peak in February 2008 (which was the low-point unemployment rate in the previous cycle).

You can see a very flat V-shaped recovery with a positive trend – the national economy overall has now gone past the peak of July 2008 which is good news and will drive down underemployment.

State by State

Last month I considered the claim that had started to appear in the media as to whether the recovery phase was defining a two-speed economy where the “mining” regions (Western Australia, Queensland and Northern Territory) were driving growth and the old manufacturing areas (NSW and Victoria) were stagnating.

This is also relevant in light of the current political fiasco where the mining companies are resisting the introduction of a modest resource rent tax (stupidly terms a super profits tax by the Government) and spending millions on misleading advertising. The mining lobby has somehow managed to convince people that the industry is huge (it is not), that is saved us from the global financial crisis (it did not at all – it contracted more than most industries) and the tax will turn us into a communist state [if only! (-:]

Anyway, in the analysis last month there was no evidence to support two-speed hypothesis. The states with significant exposure to mining were not recording as strong employment growth.

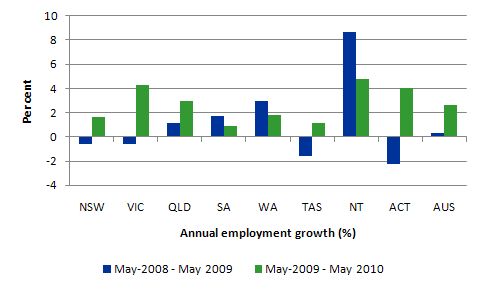

I am just monitoring these trends at the moment. The following graph shows the percentage employment growth for the states and territories for each of the last two years (to May). There is nothing special about the periods chosen – just to correspond with the latest observation. The choice doesn’t really change the message.

You can see that the strongest employment growth is in the Northern Territory (although it is a tiny labour market). The old manufacturing stronghold of Victoria (VIC) and the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) are next.

The strong employment growth in the ACT, given it is a public sector economy (seat of government and main government departments are there) reflects the benefits of the fiscal stimulus and the modest expansion of government. Remember not to get tricked by scale. The ACT is a much smaller labour market in absolute terms than NSW and Victoria.

In the most populous states (NSW, VIC and QLD). NSW and Victoria are the manufacturing strongholds and have very little exposure to the mining industry. Queensland has some exposure to the mining industry clearly but also is probably benefiting from domestic-sourced tourism as our exchange rate appreciation makes holidaying abroad more expensive.

Importantly, states with significant exposure to mining like Western Australia are not recording strong employment growth,

So overall, while this analysis is crude, the data does not indicate a two-speed economy is emerging and doesn’t suggest any primacy in employment growth in the mining states. More detailed industry analysis will be available next week when the ABS publishes the detailed labour force data for May 2010.

Conclusion

While the business economists are claiming that the labour market is strong the facts are somewhat different. There is some growth especially in full-time employment and that is a good sign because it is contributing to the sharp increase in aggregate hours worked. This impact, in turn, is helping bring down underemployment.

But employment growth slowed overall and is barely keeping pace with population growth. Further, the usual signs of a strong recovery (rising participation) are absent. In fact, in the last month, the participation rate fell.

The combination of a slowing employment growth and falling participation do not usually augur a dynamic and fast growing economy. Taken together with the other data we are seeing on housing etc, the tentative conclusion is that growth overall is very weak. The National Accounts data for the March quarter clearly showed that without the fiscal stimulus we would have been in recession. That stimulus is being progressively withdrawn now and there is no sign that private spending is really ready to step up to the plate.

The other thing to note is that the fall in the unemployment rate (and unemployment) was almost all due to the falling participation rate. So we have substituted hidden unemployment for official unemployment. Given both cohorts would accept a job if one was offered to them, the overall wastage of productive labour remains the same.

You cannot escape the conclusion that the boost provided by the fiscal stimulus is waning.

Given today’s data and related data releases over the last few weeks, I am still of the view that a further fiscal expansion is required – and should be directly targeted at public sector job creation and the provision of skills development within a paid-work context. That would be a great boost to low inflation growth.

That is enough for today!

I can’t wait for the old conservatives that govern the economy/labour market to retire and then us young people can rule the place. That’s what I always say to my boss at work, which could soon mean a further increase the unemployment rate.

cheers

Dear Bill,

I’ve just started reading your blog having recently got into monetary economics after encountering ‘the Ecology of Money’ by Richard Douthwaite, ‘the Grip of Death’ by Michael Rowbotham, and ‘New Paradigm in Macroeconomics’ by Richard Werner. Some of your own books are on order. I was heartened that you also take an interest in climate change and permaculture, topics that really motivate (and concern) me. I was wondering how you square the following circle. Judging by the blog, your basic normative economic perspective is growth oriented, to maintain full employment. But economic growth, particularly within the developed world, is the main driver of climate change. What would the implications be for MMT of non-growth economics and can this be squared with full employment? Or do we need to abandon full employment, if we think (as I’m inclined to) that saving the planet is more important? I would love to hear your views on these issues, which to me are where the real frontier social and economic issues are currently at.

Best Wishes,

Nick

NickB, good questions. They are questions I encounter regarding MMT also, which some progressives see as just another way of continuing business as usual.

MMT just describes the modern (post ’71) monetary system and explains how it works. This suggests principles of monetary and fiscal policy along the ones of Abba Lerner’s functional finance. It also provides a version of macro based on sectoral balances, as developed by Wynne Godley.

This view then has to be applied to specific data and particular circumstances to be useful. One on hand, it provides an understanding of current conditions, and on the other, shows what the different policy options are. Choice among options is a political matter, hopefully to be decided democratically after informed debate and due deliberation.

MMT just deals with what is possible given the data. Why is this such an advance over the present mainstream approach. The present approach is theoretical, based on assumptions that are not empirically grounded and often just implausible if not already disconfirmed. MMT is non-ideological, and it can be applied in a variety of ways, across the political spectrum.

Moreover, in approaching problem-solving at the global, international, and national levels, everything relevant has to be taken into account, not just economic “efficiency” in producing unlimited growth. It is obvious that unlimited growth is unsustainable with limited resources. The challenge facing humanity is to optimize resource use for general welfare and prosperity. This is going to involve conservation, technological innovation, and what R. Buckminster Fuller called “design science,” as doing more with less, e.g., by removing dead weight. This is as much an engineering problem as an economic one.

Moreover, moral and ethical issues are involved, so it is at bottom not just facts but also norms that are at issue. Without acknowledging the genuine philosophical issues, the debate revolves around arguments over subsidiary issues like efficiency. Political differences are philosophical ones, although they are often disguised as economic ones. In general, MMT’ers generally take the philosophical position that government is about providing for public purpose, rather than merely providing personal security and protecting property rights. This does not imply that MMT’ers are “socialists,” however.

Many MMT’ers are libertarians of the left without being social anarchists. They agree that while democracy may be flawed in many ways as it is practiced, it is the best system yet devised. They also agree that markets are the optimal means for price discovery. So MMT should not viewed as any kind of proposal for government takeover. They are aware that democratic government is susceptible to capture from the right and left, and many see present governments as being largely captured intellectually by the right at present. Since this is generally the direction “pro-growth” comes from, I would say that most MMT’ers are opposed to that in its present form, which clearly is not working.

MMT provides a solid financial and economic understanding for approaching this challenge based on how the system presently works, how it might be changed to improve it, and what the options are for dealing with present challenges. One of the greatest “obstacles” is thought to be insufficient funds. MMT shows that this is not the real problem. Economics always comes down to real resources and their distribution. Money just facilitates transactions as a medium of exchange, provides pricing or resources and accounting records (unit of account), and stores value, allowing for saving as deferred consumption, as well as debt financing that draws demand forward. Money just “greases the wheels” of commerce, and the issuer must ensure that just right amount of grease is provided to reduce friction to prevent seizing up (deflation) without gumming up the works (inflation).

So MMT per se says nothing a priori about conditions, e.g. through assumptions. It provides a lens for viewing data a posteriori, and a matrix (sectoral balances) for organizing it and extrapolating from it. This suggests possible options for fiscal and monetary policy, as well as dealing with money creation by banking as a public/private partnership, e.g., in light of Hyman Minsky’s financial instability hypothesis and Irving Fisher’s debt deflation theory of depressions.

It is quite clear at this point in time that present conditions require a sustainable approach. MMT offers a reality-based framework for approaching that challenge in contrast to an ideological one that is based on myths.

“This does not imply that MMT’ers are “socialists,” however.”

– so what do you call the objective of minimizing rentier incomes?

“So MMT should not viewed as any kind of proposal for government takeover.”

– thats exactly what “no bonds” is

Socialism is amorphous, but generally refers to government ownership of heavy industry and social guarantees. Setting interbank rates to zero will not accomplish this, neither will it reduce rentier income, even though the latter is also poorly defined.

“neither will it reduce rentier income”

what are you talking about?

of course it will

no bonds forces the banks to hold all government liabilities, except circulating currency

that’s socialism

and MMT’ers themselves admit that the objective is to minimize rentier income

Well, Banks are free to lend and hold those loans as assets. That is what they are supposed to do anyways. And not too many of them will complain at having low funding costs.

Moreover, there is no correlation between call money rates and capital’s share of income. The latter has been roughly constant. If anything, capital markets cheer when there is a rate cut, as the real rentier income is driven by borrowing — really dissaving. It is the flow of dissaving that generates rentier incomes, not how that dissaving is financed.

I guess all of this depends on your definitions. If you define rentier income solely as income received from holding government bonds, then by definition not selling those bonds will reduce that income. But that is a meaningless definition in terms of social welfare.

If you define rentier income as income received from non-wage sources — i.e. from ownership of the means of production — then capital’s share of income will remain at 35% whether the government sells bonds or not. It may shift from short term to long term bonds, or from bonds to equity, but someone holding a broad portfolio of assets wont notice the difference.

Anon: You need to define what you call socialism. Reducing rentiers’ income isn’t it. Paying taxes reduces rentiers’ income, so that doesn’t do it unless you think taxes are the same as socialism. Similarly, I don’t understand why you say forcing banks to hold excess reserves at a low or zero interest rate is ”a government takeover”. It’ll reduce bank profits somewhat but again so will taxes. Granted it reduces the portfolio choice for bonds of rentiers, but I don’t see how that’s a government takeover or socialism. I think ownership and control of capital and issues of distribution should figure in a definition.

RSJ: Could you please explain the last sentence in your 6:39 post. Thanks.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Socialism

http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/socialism

Keith,

As I said before, this really depends on your definitions. Economists define rents as income greater than the marginal product. In that case, with monopolistic competition, there are always rents, but that definition is heavily dependent on whatever aggregation shortcuts you take.

I would prefer do define a rentier as someone receiving income from ownership of financial claims. They may or may not also work. They may or not be wealthy. But this is a measurable definition that is independent of theory and addresses the issues that MMTers *mean* when they talk of rentier income — e.g. a decline in capital income that would result in an increase in the labor share of income.

Now let’s look at households. During a given period, each household receives some income from financial assets and pays income from financial obligations. So each household has a net-income from the financial markets, which may be negative. Call this financial income. Those households with financial positive incomes are rentiers, and the sum total of this income is rentier income.

Likewise, each household has a net income from the goods market (which includes proceeds of selling your labor) — and this may also be negative. Call this “goods income”.

In all cases, we have, during a given period:

The sum is taken over all households. “external” refers to the the business, government and foreign sectors (all other sectors).

Now collect all the household financial income terms that have a positive sign in them on one side of the equation, and move everything else to the other side:

total rentier income = (total household net borrowing – sum of external financial income) – (sum of goods income + sum of external goods income)

The first term here is total net dissaving of households plus the net dissaving of the foreign, business, and government sectors. We can call this “total dissaving”.

The last term is just net exports, as all other terms cancel out. E.g. the labor income received by households cancels with the wages paid by firms, etc.

So we have

Therefore rentier income is determined by the sum total of net dissaving by each actor — other households, firms, and government, not by the specific instrument issued, or how that dissaving is financed.

This is why the capital markets love rate cuts, and generally love low interest rates. To the degree that reduced borrowing costs encourage more borrowing, this increases rentier incomes. To the degree that high borrowing costs discourage borrowing (and they do, if they are high enough), this decreases rentier incomes.

This is the exact opposite of the fallacious belief that high borrowing costs increase rentier incomes.

The reason why the “micro” view is wrong at the macro-level is that the interest payments made subtract from spending elsewhere, and this lowers business revenue, which lowers dividend and interest income. That reduction in revenue is offset by an increase in revenue to the banks. So a hike in interest rates, holding the quantity borrowed fixed — merely shifts the income of rentiers so that they receive a little less from their ExxonMobil holdings and a little more from their MorganStanley holdings — the sources of incomes are shifted around a bit, but total rentier income is unchanged.

All that really matters is the amount borrowed by others, not the terms of repayment. And this is why rentiers love rate cuts.

And it is puzzling why a group of people that supposedly adhere to accounting identities continue to repeat this utter nonsense and about high interest rates promoting rentier incomes and low interest rates reducing rentier incomes. This is a classic fallacy of composition error, and all the big names on this board — you know who you are — should know better.

Trends In The Rentier Income Share In OECD Countries, 1960-2000

“And it is puzzling why a group of people that supposedly adhere to accounting identities continue to repeat this utter nonsense”

It is impossible to even begin to describe how confused you are on this. You are lost in “net financial asset land”.

The relationship between the level of interest rates and the share of interest income in national income is very evident from the structure of the national accounts.

Anon, there was absolutely nothing coherent in your post *except* the easily refuted statement about national accounts. It is not just interest payments, but all returns to capital that you need to measure — that includes dividends as well as proprietor income. The national income identities refute your claim, as does tax data. Saez has done good work on this as well. The rest of your comment about NFA was just babbling — I wasn’t talking about NFA at all, but about rentier income.

Oops — wrong link. I gave the link to rentier income as measured by the CBO from tax data. this is the link for dividend + interest income + proprietor income from the national accounts. It remains constant even though rates have changed greatly over the same period.

That’s an interesting study, Tom. It seems that they define rentiers as only bondholders plus all corporate profits in the financial sector, which is why their curves deviate from the capital’s share of income curves. But even then, the curves are not correlated with interest rates, but tend to rise even as rates fell. In all of these discussions, you need to define what you mean by rentier up front, otherwise there wont be any progress made. For some reason, holders of equity are ignored on this board, even though in reality everyone receives capital income from a blend of equity and bonds, and equity income is roughly double bond income. And then you have convertibles, preferred shares, and other more exotic instruments.

Anon,

“so what do you call the objective of minimizing rentier incomes?”

Georgism. Rents are not “profits” nor “wages”, in the classical sense of the term. On this view, MMT has much in common with Ricardo, JS Mill, Adam Smith etc. (whoa, all those socialist right there!), You will notice “rentier” incomes (particularly, in real estate markets) precede all major downturns – panic of 1819, 37, 57, 73, 93, 1907, 29, 55, 75, 90, 2007 – as resources for output and investment (i.e. production) are allocated to rent-seeking activities.

Reducing rentier incomes? You say that as if its a bad thing.

“thats exactly what no bonds is”

MMT teaches us that tax revenues are obselete (so perhaps it has a libertarian streak to it, as Ruml realised?); anyways, it also teaches us (1) the private sector loves a safe asset (so the “market” is really irrelevant when it comes to bonds in a fiat currency system – the private sector loves bonds as an asset – just ask Japan) and (2) with bonds government merely recoups what it has already spent prior to issuing the bonds. That is how our monetary system works.

And just using ad hominem words like “socialism”, “government takeover” etc is no substitute to reasoned, empirically-informed discussion.

Your two premises are dismissed.

From your own source:

“The United States displays a dramatic increase in the years prior to 1989, a peak in 1989, and an equally

dramatic decline after the peak year. By the late 1990’s, rentier income share in the United States had

declined to the level it had been in the mid-1970’s. Other countries that display this trend are Australia

(peak = 1989), Norway (1990), Finland (1992), Canada (1990), Portugal (1991), Spain (1993), and

Greece (1991). The increases and declines of rentier income share in these countries are dramatic.”

Could the relationship with interest rates be any more obvious?

“No bonds” assumes zero interest rates – there’s no point in no bonds otherwise.

A permanently zero risk free rate means all returns to capital are minimized. That’s socialism.

“Therefore rentier income is determined by the sum total of net dissaving by each actor – other households, firms, and government, not by the specific instrument issued, or how that dissaving is financed.”

This is drivel.

Net income on financial assets is easily derived from the national accounts.

Anon: A permanently zero risk free rate means all returns to capital are minimized. That’s socialism.

That’s your own definition of socialism. See standard defs above.

If we aren’t going to use words in their accepted meaning, I’m not sure how an objective debate can be conducted. If you want to call in something like “Anon’s concept of socialism,” I’m OK with that. After all Glen Beck and Sarah Palin have their own concepts of socialism,” etc., and I guess they are entitled to their own views as long as they make their definitions clear and distinguish them from what the accepted definition is.

The government taxing people, not issuing bonds, etc. is NOT the accepted meaning of “socialism,” no matter what Libertarians believe the English language means. (I am not saying you are a Libertarian). I’m pointing out that there is no communication across the an existing divide because the parties are not speaking the same language.

“If we aren’t going to use words in their accepted meaning”

It’s not my definition; nor is it my concept.

It’s descriptive of a policy that has a socialist orientation.

If you disagree, how else would you characterize a policy that is consistent with:

“A permanently zero risk free rate means all returns to capital are minimized.”

The replacement tax effect is unknown. But the interest rate policy crushes existing returns to those who save in the form of financial assets – not only existing returns on government bonds, but the risk free component of non government returns (before the addition of the risk premium), as well as the risk free component of equity returns (before the addition of the risk premium).

It’s a fundamental reduction in the return to capital.

How else would you characterize it?

I think the question should be phrased as: “Since the yield curve is exogenous or can be made exogenous, what should the central bank do ? ”

The Taylor rule that it follows is based on the NAIRU myth.

This paper by Louis-Philippe Rochon looks interesting to me Interest rates, income distribution, and monetary policy dominance: Post Keynesians and the “fair rate” of interest. I have a copy, though I wish copyrights would allow me to share it.

I liked RSJ’s point that the phrase “rentier” is not well defined. I wish I knew more about the phrase to participate in this interesting discussion.

I like the rule of setting the overnight rates to zero, though I want to get involved in a debate/discussion about it. RSJ has some points about equity price bubbles and I also may have some thoughts like that but with a different view. I also would like to discuss the implementation of the rule because I think the issue of collateral is important.

The banks’ balance sheet in the Kansas CoFFEE rule is simplified to

Assets – Reserves, Loans, Real Assets

Liabilities – Deposits, Funds owed to the central bank.

There is no securitization, and no government bonds, and no collateral for central bank advances.

‘rentier’ is a dumb, old fashioned word that economists like to use

what we’re talking about basically is return on financial assets

that’s consistent with Keynes and Kalecki

the existing system has dual monetary and fiscal policy

MMT wants to eliminate existing monetary policy from the mix

it does that by eliminating discretionary interest rate targeting

it sets rates at zero and leaves the rest up to taxes

and it eliminates bonds

the effect of eliminating bonds is to eliminate market pricing for expected monetary policy

since there is no risk under expected monetary policy under MMT, this is a justification for eliminating bonds

the entire proposal strips out a positive risk free rate and a term structure for the risk free rate from the pricing of all risk assets (risk free return plus risk premium = 0 + risk premium)

the full effect is to compress returns on capital as much as possible – that hurts people who save in the form of financial assets, and MMT doesn’t give a damn about it – in fact it embraces that objective

the idea is to squeeze returns to capital and transfer the difference over to labour

“the idea is to squeeze returns to capital and transfer the difference over to labour”

Maybe.

It seems you have a problem with actually paying people who work instead of letting people who think the world cant run without “their” money call all the shots.

“It seems you have a problem …”

I have a problem with the policy objective of stripping income from people who’ve saved.

Anon,

“I have a problem with the policy objective of stripping income from people who’ve saved.”

The reply would be: people are free to invest in other securities such as corporate debt and equities. Now one can argue that if overnight rates are brought down to zero other interest rates will also be less. The counter argument may be that low interest rates are good for employment. Of course the no bonds proposal goes along with the JG program proposal as well, but there is a hierarchy in the society and not everyone would be willing to work at the wage level set and hence the government needs to be good to people who are not in the low end in the wage spectrum.

Just some thoughts. Not arguing one way or the other.

Anon,

Further the argument you may be confronted with is – the savers don’t really fund anything, its investment which leads to saving etc. So its not that the savers are really helping the production process. Etc.

the idea is to squeeze returns to capital and transfer the difference over to labour

Brilliant deduction, but not stated quite correctly, I would argue.

The term “capital” has several meanings:

Investopedia

The first meaning is the economically precise meaning, e.g., as in Y=C+I+(X-M). “Investment” means expenditure on capital goods.

Return on capital is “a measure of how effectively a company uses the money (borrowed or owned) invested in its operations. Return on Invested Capital is equal to the following: net operating income after taxes / [total assets minus cash and investments (except in strategic alliances) minus non-interest-bearing liabilities]. If the Return on Invested Capital of a company exceeds its WACC, then the company created value. If the Return on Invested Capital is less than the WACC (weighted average cost of capital), then the company destroyed value.” (Investopedia).

Return on capital is profit resulting from production, just as wages are the fruit of productive labor.

The trading of finance assets is properly called speculation rather than investment, since it is not directly related to production. Therefore, this is “unproductive” and if excessive becomes parasitical by diverting funds from productive investment and compensation for production into non-productive channels.

So this is not “socialism” either, because it leaves the means of production in the hands of capitalists, i.e., those who take real risk through investment in production, rather than financial risk through speculation. This, as I understand it, is more or less what Keynes meant (although I may not have stated it well).

Regarding no bonds and interest rates. I have two reasons for wishing to see the US government cease debt issuance. First, under a fiat system it is unnecessary and Ockham’s razor should therefore be applied for efficiency. Secondly, the use of bonds in a fiat system is for convenience of the CB in setting monetary policy, which boils down to managing in interests rates. Investing a small unelected and unaccountable group of technocrats control over setting the price of money for an entire society is anti-democratic and anti-capitalist. I offer Hayek’s eloquent, The Use of Knowledge in Society, in defense of this assertion. Moreover, the Fed in non-compliance with its dual mandate to maximize price stability and employment by using interest rates in setting to target inflation, with unemployment as a trade-off.

It can also be argued that fund parked in risk-free government provided securities with the reward of interest not based on risk diverts funds from other uses, in particular productive investment. As a result, it results in a subsidy, which is a dead weight.

At least, that’s the way it appears to me.

There is a rule called Fair Rate Rule according to which the real rate of interest should be equal to the trend rate of growth of labor productivity. With such a rule, if I save an amount equal to one hour of work, I can obtain a purchasing power equal to one hour of work in the future. So in some sense “fair” for the savers.

“Further the argument you may be confronted with is – the savers don’t really fund anything, its investment which leads to saving etc. So its not that the savers are really helping the production process. Etc.”

That’s a very dangerous and erroneous argument.

Saving is forced at the macro level but elective at the micro level. To the extent there is product of some sort on the shelves, nobody at the micro level is forced to save.

Those who have elected to save have their own claim on macro saving, macro financial assets, and macro investment.

You might call the argument in question the fallacy of decomposition.

anon: There is a big difference between the ability to save from income, which implies an adequate income to do so, and the ability to save from savings. The easier the prior is, the less need there is for the latter. What is it you don’t like about that? I agree that there should be a possibility for individuals (not corporations) to hold risk free assets to a certain extent and earn income on them in line with overall growth (which they after all helped support with work). And most MMTers would support a guaranteed claim on real real services for the aged and ill in exchange for portion of income, depending on the state of the economy. That is also akin to saving, and has the benefit that it leaves no room for corporations to ‘invest’ those savings in claims on the very produce the people are producing. I think the big issue is the illusion that capitalism as we know it constitutes some sort of meritocracy. Arguing that if one manages to play the system one will be awarded by it, is tautological. Tell me who deserves how much of what we make and why.

“There is a big difference between the ability to save from income, which implies an adequate income to do so, and the ability to save from savings.”

I can’t address the rest because I don’t understand that.

It sounds like you’re opposed to compound interest.

“The term “capital” has several meanings”

I was using the term loosely in the sense of financial assets. I recognize it departs from normal use in economics, but it is common to use it that way in financial markets.

You have to be quite careful with that WACC reference/application. What it really means is that ROC WACC. That has to do with the stability of the market value capitalization of book value. In fact, ROC<WACC is still quite consistent with increasing book value, which reflects normal value creation through income.

“The trading of finance assets is properly called speculation rather than investment, since it is not directly related to production. Therefore, this is “unproductive” and if excessive becomes parasitical by diverting funds from productive investment and compensation for production into non-productive channels.”

Without questioning the blanket of “speculation”, I do question the funds “diversion” meme. Economists should be more circumspect about this. Trading existing financial assets is a zero sum game. It’s pervasive and has to do with personal freedom to manage one’s financial asset portfolio.

Productive investment usually requires new financial asset creation. It’s not clear to me that the acceleration in trading of existing assets has prevented investment and new financial asset creation. To some extent, its comparing apples and oranges.

Look, this is simple. I am defining rentier income to be capital income. Capital income — according to NIPA as well as tax records — has stayed roughly constant in the U.S. In other nations, it has risen somewhat. All this time, rates have been first rising until 1980 and then falling to zero. Therefore you cannot argue that capital income will decline (and therefore labor shares will increase) if the call money rate is set to zero.

Regarding the study Tom cited, they show capital income rising from 1980 to 1989, when rates were falling. Over that period, a negative correlation. Over the longer period, a positive correlation. Why? Because the authors define rentier income to be only bond income, but not dividends — except for the financial sector. All financial sector profits are rentier incomes to the authors. In that case, the global housing crisis/bank crisis in the late 80s/early 90s led their definition of rentier income to decline.

Regardless of whether the government sells bonds or not, the private sector will sell both bonds and equity, and having low overnight interbank rates is not going to drive the risk-adjusted returns to zero. Bank lending is marginal to these markets. What is important is the cost of equity. A business has the option of raising funds from bonds or from equity — either selling more equity or paying fewer dividends. The bulk of investment is from equity, not bonds, and the bulk of capital income arises from ownership claims rather than rental claims. When talking about rentiers, Kalecki was referring to both — both the receivers of business profits ex-interest as well as the receivers of interest payments.

In reality, it is the same group of people. The discount rate is determined from the equity costs, because that is the trade-off that the borrower — the owner — faces. The business is not able to obtain funds from a bank, as bank loans cannot replace credit market instruments.

And we can see this at work historically.

During the post-war period, bond yields were low across the board — there was an enormous fear of risk — and as a result, businesses were able to lever up, obtaining funding that was (ex-post) too cheap from debt and therefore supplying (ex-post) excessive dividends. The result was a historic equity boom that burst in 1966. Funds were transferred from rentier interest income into their dividend income. But the total rentier income did not decrease.

During the 80s, bond yields were (ex-post) too high and as a result dividend income was suppressed and interest income rose. Note that I am talking about the income flows here, not the yields. In both cases, total rentier income remained constant.

In all cases, having low overnight rates may or may not encourage excess real estate borrowing, which may or may not boost capital income. It will certainly not decrease capital income, neither will the lack of bonds suddenly allow capital returns to fall to zero. Capital returns will remain set by opportunity cost, and over long run time periods, they will be equal to the growth rate of the economy — assuming that the growth rate of the capital stock increases with the same rate as the economy as a whole.

“First, under a fiat system it is unnecessary and Ockham’s razor should therefore be applied for efficiency. Secondly, the use of bonds in a fiat system is for convenience of the CB in setting monetary policy, which boils down to managing in interests rates.”

The first depends on whether you eliminate monetary policy with zero rates. If you do that, then agreed you may as well do away with bonds for efficiency. But you don’t do the first without the second.

the risk free rate is an embedded component of both bond and stock returns

you can’t argue that one offsets the other when the risk free rate is being stripped (set to zero) for both

Ramanan

Unfortunately interest rates are not set by a sense of fairness — which is great, because judging fairness is subjective — but because of arbitrage. A business can either borrow from the bond markets or it can retain earnings (borrowing from equity). When yields fall (and capital gets too expensive) — we can make more! There is not a fixed supply. So the cost of capital (which is the return on capital) is not set by the financial system, but by the real economy. How much of that return is captured by the financial sector, as opposed to other sectors is set by regulation. Lowering funding costs for the financial sector is not going to drive capital returns down, but it may drive the financial sector’s capture rate up. Whether it does or not depends on the associated bank regulation. The proposals here are to forbid banks from holding any asset other than bank loans that they hold to term. In that case, the remaining risk is one of real estate bubbles, since that is what banks lend against. If, in addition to that you prevent banks from enabling real estate bubbles, then the remaining risk is that they will earn excess returns. If in addition you tax them heavily to ensure that their profits are in line with the non-financial sector (and you need to prevent them from earning labor rents as well), then the zero interbank rates wont affect the economy at all. Everything will go on as usual, except that the short term rates will be a little lower and long term rates will be a little higher — the yield curve will be steeper, but again you will be taxing the hell out of banks to prevent them from earning an excess profit from this.

The first depends on whether you eliminate monetary policy with zero rates. If you do that, then agreed you may as well do away with bonds for efficiency. But you don’t do the first without the second.

Yes, that is what I am proposing. As I see it, they go hand in hand.

I would also separate retail banking from finance other than homeowner mortgages. I think that government should be involved in retail banking to the extent necessary, but it should stay out of finance other than as referee to ensure no cheating and no usury.

It has also become clear that government has to be involved in reducing/eliminating systemic risk. This should be done insofar as possible by changing incentives but regulation, including anti-trust legislation, will likely be required, too. Too big to fail creates an implicit subsidy/dead weight that distorts the mechanism of risk, which is at the heart of free market capitalism.

To “strip” credit risk, you look at returns ex-post. Ex-post, or risk-adjusted returns, average out to the risk-free returns. Having no risk-free bonds does not mean that the risk-adjusted return goes to zero. Just because you are getting rid of a tool to measure the risk-adjusted returns does not mean that the risk-adjusted returns go away.

Just because the yields from equity and bonds can be measured as a credit-risk premium over long term government bond yields does not mean that if that measurement tool is removed, that there will be zero risk-adjusted return. That is a massive confabulation. The risk-adjusted return, or the ex-post return will continue to average out to be the growth rate of the economy.

sorry, i’m neither a native speaker nor an economist. i’ll try to keep it simpler in future. one more attempt to clarify: first, there is no way to asses a ‘just’ distribution between wages and returns on capital. every system will produce its own outcome and inequalities (moral ineptitudes), which over time will compound and thus be exacerbated. any attempts to counter these inherent systemic failures without introducing a new system will incorporate redistribution of some sort, but that doesn’t make it socialism.

about bonds: it seems to me that they are claims on labour output with a guaranteed return on investment but with nothing to back them to merit the term investment. so while i find those who have contributed to output may be given a limited privilege of profiting from such an asset as a distributive gesture (from who to whom, i wonder?), there is nothing in my mind that would merit such an opportunity for all.

Oliver, there is absolutely nothing *guaranteed* about bonds. Only government bonds are guaranteed, and what is confusing the hell out of everyone on this board is the fact that in a growing economy, there will always be a positive risk-adjusted return.

If there were no government bonds sold, any investor could still purchase a broad basket of bonds (and stocks), and those assets would only simultaneously default if the entire economy collapsed to zero, in which case his government bond holdings would not help him.

The purchaser of the broad basket of risky instruments gets the same return as the purchaser of risk-free instruments, at least over long time periods. And it just bothers people to no end that there is a positive risk-free return — they are absolutely convinced that someone is getting something for nothing. But the “cost” of that return is just the opportunity cost of investing in a growing economy. Wages will grow, capital will grow, productivity will grow — everything is growing! And so the assets will also grow, and the growth rate of the assets is equal to the yield.

4:55

why don’t you read the earlier comments instead of making it up

Anon, you argue that just because no government bonds are sold, that suddenly the risk-free rate must be zero.

I am arguing that the risk-free rate is just a proxy for the risk-adjusted rate. Due to arbitrage. The risk-free bond yields tell us what the expected risk-adjusted yields are, modulo all the government interventions that add noise to this data.

But you are confusing a way of measuring perceptions of the the ex-post return with a way of controlling the ex-post returns. The ex-post returns — which are the returns after risk is removed — will continue to be positive, and they will continue to be the growth rate of the economy.

“Anon, you argue that just because no government bonds are sold, that suddenly the risk-free rate must be zero.”

No I did not.

Read the comments.

RSJ @ 4:47,

I was actually talking of a rule to set the interest rates not about the behavior at present. There are so many interest rates and the question is “which interest rate”. I haven’t gone through seen this part in the PKE literature, though in general I find their work very satisfying. I do not know the answer at present but I believe one can achieve something like that. It could involve some payment from the government to household accounts by directly crediting their bank deposit accounts. (just guessing). The other interest rates or yields can do whatever they want because households volitionally bought those securities.

The important question to debate is what should be the monetary policy? The present central bank reaction function is something which is based on incorrect economic reasoning.

For each maturity, there can only be one risk-adjusted rate, which is also the risk-free rate. There cannot be two. Otherwise, what lender would lend at the lower rate instead of the higher rate?

rsj. thanks for clarifying. i think i see what you’re getting at (slowly, very slowly). btw. i was always talking about government, not corporate bonds. re rate of return: maybe a question for to help me understand: why aren’t wages paid in something equal to government bonds that guarantee the same return? why the two-tiered system?

If you’re still trying to figure it out, I said the elimination of monetary policy (zero rates) was the justification for the elimination of bonds. Bonds yields are the market’s view on expected monetary policy and the risk around expected monetary policy. When the risk of monetary policy is removed (rates permanently fixed at zero), there is no reason to have bonds. That doesn’t mean you can’t eliminate bonds while maintaining non-zero rates. But that’s a weaker case for MMT. The preferred MMT proposal is eliminating both.

But this is complete nonsense:

“I am arguing that the risk-free rate is just a proxy for the risk-adjusted rate. Due to arbitrage. The risk-free bond yields tell us what the expected risk-adjusted yields are, modulo all the government interventions that add noise to this data.”

I can’t imagine what you’re trying to say here.

Anon @3:58

agreed!

Anon, the government will only stop selling government bonds. The private sector will continue to sell bonds, which have a positive risk-adjusted return. For a specific bond, you will still decompose the interest rate into a credit-risk term and a risk-free term, and the risk-free term will remain non-zero, even though there are no government bonds. It will just make the pricing of the private sector bond a little more difficult.

If you don’t understand why the risk-free rates are the same (on average) as the any other ex-post return, then I can’t help you.

anon@ 2:01

“the entire proposal strips out a positive risk free rate and a term structure for the risk free rate from the pricing of all risk assets (risk free return plus risk premium = 0 + risk premium)”

Here, you are arguing that the government is able to set the risk-free return to zero. I am arguing that the risk-free return is nothing more than the risk-adjusted return, on average, and that this will not be zero. This seems to confuse you. I can’t help you with that. The term structure will remain there, and it will remain positive. It will be more difficult to measure because you can’t determine it from looking up government bond yields, but nevertheless for all bonds

rate charged = risk-free rate + risk-premium = anticipated risk-adjusted return + risk-premium, and both terms will remain non-zero regardless of what the government does with fedfunds or bond sales — at least for the longer end of the curve.

Anon,

I guess what RSJ is trying to say is that if we don’t have government bonds, the yield for one particular maturity does not imply the default rate. For example if the one year rate on a corporate paper is 2%, (in the absence of T-bills), it doesn’t necessarily translate into a 2% probability of default. At a more technical level, the instantaneous forward curve is not the hazard rate curve if government yields is zero.

“Anon, the government will only stop selling government bonds. The private sector will continue to sell bonds, ”

Good grief!

I know that.

“This seems to confuse you.”

It is you who are confused, and not for the first time.

In the scenario, the government sets the risk free rate at zero, by policy.

If the policy rate is set at zero permanently, and if the market believes the commitment of the policy, then the forward rates for the risk free rate are zero, and the implied risk free yield curve embedded in risky bonds is zero. Risky bond yields consist of the risk premium only, unlike today, where they = non-0 risk free rate + risk premium.

you are completely confusing risk adjusted return with risk free rate

Oliver,

Wages are income, and all income is paid in cash, whether that be dividend income or wages. What you do with that income is a separate question.

In arbitrage-free markets, the two are the same. Really I don’t have time to teach you these things, and you shouldn’t be commenting on here if you don’t know the basics.

Of course in the “real” world, the returns are not known, but there is no reason to believe that one is always higher than the other. On average, these errors will cancel out.

Given your persistent bluffing and BS about basic finance matters, your own comments here are a public disservice.

Risk adjusted return and risk free rate are completely independent – but very consistent with my earlier comments about MMT risk free stripping:

————————————————————————————————————————–

To calculate risk-adjusted return, subtract the risk-free rate from the investment’s return, then divide the resulting number by the standard deviation of the investment’s return. The value of a risk-adjusted return lies in its ability to reveal whether an investment’s returns are attributable to smart investing or excessive risk-taking. Risk-adjusted return is a useful tool for factoring volatility into investment decisions.

I’ll bet Bill Mitchell knows the (fundamental) difference between the risk free rate and risk adjusted return.

Anon, you are defining the Sharpe ratio, which is the financial industry benchmark for measuring alpha.

But in an arbitrage-free market, alpha is going to be zero, which means that the mean return (or the expected return) is going to be equal to the risk-free rate. I.e. the return ex-post will be equal to the risk-free return.

Therefore the problem with using the sharpe ratio is that it assumes that investors are risk-averse and therefore they will always pay a premium for the risk-free asset, allowing for a positive alpha. But in actual markets you have risk-neutral arbitrageurs that negate the preferences of households, and drive alpha to zero.

This is in general a problem with theories of asset demand — they are not arbitrage-free theories if you reject loanable funds and simultaneously allow for risk-neutral investors. If you reject loanable funds, as I do, then the sharpe ratio (and other measures of alpha) will be zero, and as a result, the only way of measuring risk-adjusted return to take the expected return, or the return ex-post. This will be the risk-free rate. And this fits well with historical data over long time periods.

oh, so now its mean return, or expected return, to finesse the explanation

bluff and switch

bluff and switch

you never stop

here and on the other blogs

And in terms of what Bill believes, you check — he recently did a blog post about Australian super-annuation funds, outlining how their return was not in excess of the risk-free return. The australian economy, as with any other modern economy, grows at roughly the long term risk-free rate, and this is also the ex-post return that you can expect to get, CAPM scams notwithstanding.

Oh, I don’t know, Anon:

First, it was that capital returns are positively correlated with the interest rate — according to NIPA. I disproved that — using NIPA — and was met with silence. Next, you argued that not selling bonds would strip out the risk-free rates, and I called you on it. You said you said no such thing, and I provided the quote. More silence. I’ll let the readers decide about bluff and bluster.

The fact is, returns to capital — which is the Kaleckian definition of rentier’s income, and the definition that I was up-front about using — do not depend on the interest rate. There is overwhelming evidence for this. Next, although the government can certainly supply arbitrage profits to the financial sector by steepening the yield curve, such an action is not going to drive the risk-free rates to zero, nor will it alter long run yields. I think I provided a pretty good case for this, but all you provided was ridicule, and frankly — a lack of understanding. Bluff and bluster indeed.

anon, I’ll bet you have no clue (fundamental or otherwise) about socialism. So you are not qualified to make a judgement about existence or not of rentier income under socialism. Therefore your initial argument (whatever it was) is wrong.

And please stop making an elephant out of a fly once again. It is unconstructive and getting annoying.

Dear anon, Sergei, RSJ and all

Remember on this blog, we aim to argue and debate vigorously but also to keep it amicable. That requires calm tempers and a due regard and respect for each other!

I am thinking about all the comments and when I get some time I will give some views.

best wishes

bill

one final note:

you can search the finance literature until the cows come home and you won’t find an equivalence between the risk free rate and risk adjusted return

that’s because risk adjusted return always nets out the risk free rate, whatever definition you use

I responded sufficiently to your other claims, given their fragile quality

Sergei – i never claimed to define socialism; i said that minimization of returns to capital was socialism (i.e. symptomatic thereof)

Bill – nicely moderated

“he recently did a blog post about Australian super-annuation funds, outlining how their return was not in excess of the risk-free return’

so what?

that doesn’t mean the risk adjusted return = the risk free rate

it means the ex post risk adjusted return is zero

… and now for the switch

anon, capital does not formally exist in socialism as socialism by definition means socialized capital. So what is it exactly you are talking about when you say “minimization of returns to capital”?

Seriously. People can and do save in socialism as well. Whether you call it government bonds or bank deposits is not a big difference because in socialism _all_ bank deposits are socialized in terms of risk. Elimination of government bonds still retains private yield curve due to time value of money/consumption even if in socialism this yield curve is controlled by the government. So banks will pay interest on essentially risk free (term) deposits which are substitutes for government bonds which would be no longer sold due to absence of monetary/interest rate policy.

Next, though loans generate deposits banks still have to fund themselves one way or the other because of interbank settlement needs. These needs do not depend on political system, be it socialism or capitalism. The fact that this link (loan->deposit->settlement->funding) is often realized post factum does not change the conclusion that depositors participate in capital formation. In socialism this participation is credit risk free but it still pays income. This depositor income is indirect (in the sense that there is no direct financial transaction) rentier income and is part of interest rate that bank charges to _government_ owned / socialized enterprises.

So there is rentier income in socialism even if it is socialism and it abandons monetary and interest rate policy.

Yes, Bill, I’ll for my part I’ll tone down the snark.

For those wanting data, Saez has done good work tracking capital income in the U.S. Saez shows that factor shares in the corporate sector have been constant from 1929 until 2002 (figure VI of reference). In the personal sector, capital income has been rapidly rising from 10 to 20%, from 1944 to 2002 (also figure IV, referenced). As an aside, in the U.S. the real issue the distribution of the wage share (figure VIII, and also figure XI), rather than the total labor share of income.

The earlier Congressional Budget Data I cited is can be found here. Again, you can compare capital income with historical interest rates to determine whether or not there is a correlation. The story remains the same — increases in interest income are weakly correlated with rising rates, but this correlation is more than offset by dividends and other forms of capital income, so that in aggregate labor’s share does not increase when the interest rate falls.

As to whether the no bonds proposal is socialism or “strips out a positive risk free rate and a term structure for the risk free rate from the pricing of all risk assets (risk free return plus risk premium = 0 + risk premium)”, this really gets to the question of whether, in a growing economy, the interest rates charged purely reflect credit-risk or whether there is an expectation of return even after taking account of credit-risk. And more importantly, whether government can control this return expectation. And if it can control this return, will doing so just shift income into equity and away from bonds or will it really increase labor’s share of income? I think this is what is important in this discussion.

Anon is right — I should not have said “risk-adjusted rate”, but “expected return”, or “ex-post return”. Mea culpa.

The argument I was making is that although the risk-free rate currently serves as a convenient way to price risky assets, that even were the government to stop selling bonds or otherwise use monetary policy to set the interbank rates to zero, that bonds would not be priced according to “0 + credit risk”, but rather “expected return + default risk”. This is a tautology (e.g. credit risk = default risk, and the latter disappears in the expectation) — so it’s difficult to argue with this point. What Anon may dispute — I’m not sure — is whether expected return = risk-free rate. Those who believe that in an arbitrage-free market, alpha is driven to zero, will agree. Those who believe that with prudent portfolio management, alpha can be positive will disagree. It is my contention that alpha is zero over long time periods, and that the expected return over long time periods is determined by the economy, by things like technological change, and is not open to government control.

Government, when it shortens the short end of the curve, is allowing for arbitrage — on the part of banks, and those arbitrage profits are channeled to bank shareholders and creditors — again rentier income is not reduced, and if anything is increased. Any attempts to give banks access to zero overnight rates should be combined with heavy taxation of bank profits to prevent them from earning returns in excess of the non-financial sector.

The longer end of the curve is much more difficult to for the government to control, but again, any success in pushing those yields down will only result in re-routing income from one set of instruments to another — from bonds to equity or private equity.

In the end, the labor share of income will not benefit from this.

I think (in the U.S.) labor share of income is fine where it is now, and tax policy along with industrial relations policy is how you can improve the distribution of wage income. You can also use capital gains taxes to reduce capital’s share of income. This approach is better than a (futile) attempt to squeeze capital income by giving banks low funding costs. Higher funding costs would be better, as it would push down real estate prices and limit debt growth. In principle, none of this requires that the government does or does not sell bonds — lack of bond sales can be offset by additional asset fees placed on banks.

Hopefully future conversations will have less animosity.

“Anon is right – I should not have said “risk-adjusted rate”, but “expected return”, or “ex-post return”. Mea culpa.”

you see, the problem with this is that it completely changes the meaning of everything else written around it – that is, the coherence or incoherence of it according to the attentive and knowledgeable reader

and once such a fundamental and incredibly obvious error has been made – one that is absolutely pivotal to the discussion – and one that is defended with utmost resistance – well, it calls into question everything else around it

and the risk/return in even reading it

and this isn’t the first time

“Hopefully future conversations will have less animosity”

if you had started by apologizing directly, rather than whimpering to Bill, it might have assisted with this objective

but I’ve seen your style too often now, so I know better

Bill,

if you do take the time to review some of the thoughts in this particular blog conversation

kindly take note that I’ve used the word “socialism” only a very small number of times

on purpose

Anon,

just to clarify,

Are you still claiming that not selling bonds and setting the overnight rate to zero will result in “It’s a fundamental reduction in the return to capital.”?

And that it is obvious, from the national accounts, that there is a positive correlation between rentier income as defined by you (“what we’re talking about basically is return on financial assets”) and FF?

And that “If the policy rate is set at zero permanently, and if the market believes the commitment of the policy, then the forward rates for the risk free rate are zero, and the implied risk free yield curve embedded in risky bonds is zero. Risky bond yields consist of the risk premium only, unlike today, where they = non-0 risk free rate + risk premium.”

To me — those are pretty glaring errors. And what’s more important, they have serious implications for what the best policy should be.

People living outside the US and unfamiliar with what passes for “the news” may not be familiar with what this kerfuffle over “socialism” is about. Currently, the GOP doing its best to paint Democrats as “socialists” and the president’s policies as promoting “socialism.” There is not even a hint of socialism in the US in the sense of state ownership of the means of production. Most Americans don’t have a clear ideal about what “socialism” means economically and politically, only that it was the basis for both Communism and Naziism (National Socialism). Therefore, “socialism” is a politically poisonous label in the US. Conservatives unabashedly make this connection, and the media just echos it.

Conservatives connect socialism with statism. They draw a false either/or distinction between free market capitalism/democracy and socialism/statism, even though the US has a mixed economy. Conservatives in general believe that the New Deal brought socialism to the US, and they have been trying to escape it ever since. Thus, the movement to end all social welfare programs, even very popular ones like Social Security and Medicare (public social insurance programs that workers must buy into).

Therefore, it seems important to distinguish between “socialism” and “socialization.” The US has virtually no public ownership of the means of production, temporary public ownership as collateral for bailouts notwithstanding. However, every government “socializes” resources for public purpose, if only to meet its overhead.

Libertarians correctly recognize that government expenditure transfers real goods and services to public use. This involves socialization of those resources. Taxation also withdraws funds from non-government, and that can be seen as a form of socialization also. Arch-conservatives and Libertarians call for ending taxation. They make exceptions only for protection of persons and property, e.g., the military and other security forces, judicial system, prisons, and so forth.

When one labels any socialization of resources “socialism,” then “socialism” loses its fundamental meaning and is divorced from all connection with socialist systems. To conflate these connotations is just a confusion, or else a disingenuous rhetorical device. This rhetoric, picked up by the media echo chamber, is a “hot potato” for the Democrats in the US right now, due to the intense barrage from the right. It is also being used to purge GOP officeholder and candidates of anyone who is not an arch-conservative or libertarian.

The political basis for deficit terrorism is this distinction between free market capitalism/democracy/freedom and socialism/statism/”serfdom.” The size of the deficit and debt are viewed as indicators of the encroachment of socialism/statism, and therefore, the approach of serfdom. It is important to understand that this is not only an economic issue in the US. It is fundamentally an argument about political systems. So getting these terms right is important.

“I have a problem with the policy objective of stripping income from people who’ve saved.”

Why is saving a good thing at all?

I have a problem with people getting something for nothing. Savers get their income from productive capital. The return they get should be a very small slice of the pie, since they take absolutely no risk whatsoever.

For a Chicagoish view on the interest rates see The case for and against ultra-low rates – Raghuram Rajan is blogging as well.