Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

Saturday Quiz – June 19, 2010 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for yesterday’s quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of modern monetary theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

The only way that you can have unbalanced external accounts across nations (some countries with surpluses and other deficits) is because the surplus countries desire to hold financial assets denominated in the currency of the deficit countries.

The answer is True.

I note our anonymous friend has already declared that there is “No way it’s true”. Okay, I am not God. But in this case I don’t really need to draw on any divine powers anyway to defend the conclusion that it is true.

Many economists do not fully understand how to interpret the balance of payments in a fiat monetary system. For example, most will associate the rise in the current account deficit (exports less than imports plus net invisibles) with an outflow of capital. They then argue that the only way Australia (if we use it as an example) can counter this is if Australian financial institutions borrow from abroad.

They then assume that this is a problem because it means, allegedly, that Australia is “living beyond its means”. It it true that the higher the level of Australian foreign debt, the more its economy becomes linked to changing conditions in international credit markets. But the way this situation is usually constructed is dubious.

First, exports are a cost – a nation has to give something real to foreigners that it we could use domestically – so there is an opportunity cost involved in exports.

Second, imports are a benefit – they represent foreigners giving a nation something real that they could use themselves but which the local economy will benefit from having. The opportunity cost is all theirs!

So, on balance, if a nation can persuade foreigners to send more ships filled with things than it has to send in return (net export deficit) then that is a net benefit to the local economy. I am abstracting from all the arguments (valid mostly!) that says we cannot measure welfare in a material way. I know all the arguments that support that position and largely agree with them.

So how can we have a situation where foreigners are giving up more real things than they get from the local economy (in a macroeconomic sense)? The answer lies in the fact that the local nation’s current account deficit “finances” the desire of foreigners to accumulate net financial claims denominated in $AUDs. Think about that carefully. The standard conception is exactly the opposite – that the foreigners finance the local economy’s profligate spending patterns.

In fact, the local trade deficit allows the foreigners to accumulate these financial assets (claims on the local economy). The local economy gains in real terms – more ships full coming in than leave! – and foreigners achieve their desired financial portfolio. So in general that seems like a good outcome for all.

The problem is that if the foreigners change their desire to accumulate financial assets in the local currency then they will become unwilling to allow the “real terms of trade” (ships going and coming with real things) to remain in the local nation’s favour. Then the local econmy has to adjust its export and import behaviour accordingly. If this transition is sudden then some disruptions can occur. In general, these adjustments are not sudden.

This bi-lateral example extends to multi-lateral situations which become more complicated in terms of who is holding what but the underlying principle is the same.

A net exporting must be desiring to accumulate financial assets denominated in the currencies of the nations it runs surpluses with. It may then trade these assets for other claims (not necessarily in the original currency) but that doesn’t alter the basic motivation.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Modern monetary theory in an open economy

- Debt is not debt!

- The piper will call if surpluses are pursued …

Question 2:

Like anything in abundance, it is true that when there is more “money” in the economy its value declines.

The answer is Maybe.

The question is mostly false but there are situations (rare) where it could be true – so maybe.

The question requires you to: (a) understand the difference between bank reserves and the money supply; and (b) understand the Quantity Theory of Money.

The mainstream macroeconomics text book argument that increasing the money supply will cause inflation is based on the Quatity Theory of Money. First, expanding bank reserves will put more base money into the economy but not increase the aggregates that drive the alleged causality in the Quantity Theory of Money – that is, the various estimates of the “money supply”.

Second, even if the money supply is increasing, the economy may still adjust to that via output and income increases up to full capacity. Over time, as investment expands the productive capacity of the economy, aggregate demand growth can support the utilisation of that increased capacity without there being inflation.

In this situation, an increasing money supply (which is really not a very useful aggregate at all) which signals expanding credit will not be inflationary.

So the Maybe relates to the situation that might arise if nominal demand kept increasing beyond the capacity of the real economy to absorb it via increased production. Then you would get inflation and the “value” of the dollar would start to decline.

The Quantity Theory of Money which in symbols is MV = PQ but means that the money stock times the turnover per period (V) is equal to the price level (P) times real output (Q). The mainstream assume that V is fixed (despite empirically it moving all over the place) and Q is always at full employment as a result of market adjustments.

In applying this theory the mainstream deny the existence of unemployment. The more reasonable mainstream economists admit that short-run deviations in the predictions of the Quantity Theory of Money can occur but in the long-run all the frictions causing unemployment will disappear and the theory will apply.

In general, the Monetarists (the most recent group to revive the Quantity Theory of Money) claim that with V and Q fixed, then changes in M cause changes in P – which is the basic Monetarist claim that expanding the money supply is inflationary. They say that excess monetary growth creates a situation where too much money is chasing too few goods and the only adjustment that is possible is nominal (that is, inflation).

One of the contributions of Keynes was to show the Quantity Theory of Money could not be correct. He observed price level changes independent of monetary supply movements (and vice versa) which changed his own perception of the way the monetary system operated.

Further, with high rates of capacity and labour underutilisation at various times (including now) one can hardly seriously maintain the view that Q is fixed. There is always scope for real adjustments (that is, increasing output) to match nominal growth in aggregate demand. So if increased credit became available and borrowers used the deposits that were created by the loans to purchase goods and services, it is likely that firms with excess capacity will react to the increased nominal demand by increasing output.

The mainstream have related the current non-standard monetary policy efforts – the so-called quantitative easing – to the Quantity Theory of Money and predicted hyperinflation will arise.

So it is the modern belief in the Quantity Theory of Money is behind the hysteria about the level of bank reserves at present – it has to be inflationary they say because there is all this money lying around and it will flood the economy.

Textbook like that of Mankiw mislead their students into thinking that there is a direct relationship between the monetary base and the money supply. They claim that the central bank “controls the money supply by buying and selling government bonds in open-market operations” and that the private banks then create multiples of the base via credit-creation.

Students are familiar with the pages of textbook space wasted on explaining the erroneous concept of the money multiplier where a banks are alleged to “loan out some of its reserves and create money”. As I have indicated several times the depiction of the fractional reserve-money multiplier process in textbooks like Mankiw exemplifies the mainstream misunderstanding of banking operations. Please read my blog – Money multiplier and other myths – for more discussion on this point.

The idea that the monetary base (the sum of bank reserves and currency) leads to a change in the money supply via some multiple is not a valid representation of the way the monetary system operates even though it appears in all mainstream macroeconomics textbooks and is relentlessly rammed down the throats of unsuspecting economic students.

The money multiplier myth leads students to think that as the central bank can control the monetary base then it can control the money supply. Further, given that inflation is allegedly the result of the money supply growing too fast then the blame is sheeted home to the “government” (the central bank in this case).

The reality is that the central bank does not have the capacity to control the money supply. We have regularly traversed this point. In the world we live in, bank loans create deposits and are made without reference to the reserve positions of the banks. The bank then ensures its reserve positions are legally compliant as a separate process knowing that it can always get the reserves from the central bank.

The only way that the central bank can influence credit creation in this setting is via the price of the reserves it provides on demand to the commercial banks.

So when we talk about quantitative easing, we must first understand that it requires the short-term interest rate to be at zero or close to it. Otherwise, the central bank would not be able to maintain control of a positive interest rate target because the excess reserves would invoke a competitive process in the interbank market which would effectively drive the interest rate down.

Quantitative easing then involves the central bank buying assets from the private sector – government bonds and high quality corporate debt. So what the central bank is doing is swapping financial assets with the banks – they sell their financial assets and receive back in return extra reserves. So the central bank is buying one type of financial asset (private holdings of bonds, company paper) and exchanging it for another (reserve balances at the central bank). The net financial assets in the private sector are in fact unchanged although the portfolio composition of those assets is altered (maturity substitution) which changes yields and returns.

In terms of changing portfolio compositions, quantitative easing increases central bank demand for “long maturity” assets held in the private sector which reduces interest rates at the longer end of the yield curve. These are traditionally thought of as the investment rates. This might increase aggregate demand given the cost of investment funds is likely to drop. But on the other hand, the lower rates reduce the interest-income of savers who will reduce consumption (demand) accordingly.

How these opposing effects balance out is unclear but the evidence suggests there is not very much impact at all.

For the monetary aggregates (outside of base money) to increase, the banks would then have to increase their lending and create deposits. This is at the heart of the mainstream belief is that quantitative easing will stimulate the economy sufficiently to put a brake on the downward spiral of lost production and the increasing unemployment. The recent experience (and that of Japan in 2001) showed that quantitative easing does not succeed in doing this.

This should come as no surprise at all if you understand Modern Monetary Theory (MMT).

The mainstream view is based on the erroneous belief that the banks need reserves before they can lend and that quantitative easing provides those reserves. That is a major misrepresentation of the way the banking system actually operates. But the mainstream position asserts (wrongly) that banks only lend if they have prior reserves.

The illusion is that a bank is an institution that accepts deposits to build up reserves and then on-lends them at a margin to make money. The conceptualisation suggests that if it doesn’t have adequate reserves then it cannot lend. So the presupposition is that by adding to bank reserves, quantitative easing will help lending.

But banks do not operate like this. Bank lending is not “reserve constrained”. Banks lend to any credit worthy customer they can find and then worry about their reserve positions afterwards. If they are short of reserves (their reserve accounts have to be in positive balance each day and in some countries central banks require certain ratios to be maintained) then they borrow from each other in the interbank market or, ultimately, they will borrow from the central bank through the so-called discount window. They are reluctant to use the latter facility because it carries a penalty (higher interest cost).

The point is that building bank reserves will not increase the bank’s capacity to lend. Loans create deposits which generate reserves.

The reason that the commercial banks are currently not lending much is because they are not convinced there are credit worthy customers on their doorstep. In the current climate the assessment of what is credit worthy has become very strict compared to the lax days as the top of the boom approached.

Those that claim that quantitative easing will expose the economy to uncontrollable inflation are just harking back to the old and flawed Quantity Theory of Money. This theory has no application in a modern monetary economy and proponents of it have to explain why economies with huge excess capacity to produce (idle capital and high proportions of unused labour) cannot expand production when the orders for goods and services increase. Should quantitative easing actually stimulate spending then the depressed economies will likely respond by increasing output not prices.

So the fact that large scale quantitative easing conducted by central banks in Japan in 2001 and now in the UK and the USA has not caused inflation does not provide a strong refutation of the mainstream Quantity Theory of Money because it has not impacted on the monetary aggregates.

The fact that is hasn’t is not surprising if you understand how the monetary system operates but it has certainly bedazzled the (easily dazzled) mainstream economists.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Money multiplier and other myths

- Islands in the sun

- Operation twist – then and now

- Quantitative easing 101

- Building bank reserves will not expand credit

- Building bank reserves is not inflationary

Question 3:

If a national government builds a road and then tears it up again only to rebuild it again later, there is no net gain in employment and national income the second time round.

The answer is False.

This question allows us to go back into J.M. Keynes’ The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money. Many Flat Earth Theorists characterise the Keynesian position as advocating useless work – digging holes and filling them up again. The critics focus on the seeming futility of that work to denigrate it and rarely examine the flow of funds and impacts on aggregate demand. They know that people will instinctively recoil from the idea if the nonsensical nature of the work is emphasised.

Living in Australia (one of the World’s largest primary commodity exporters) I am always bemused by the notion that digging holes and filling them up again is futile work. It seems to characterise our mining sector very well.

But that aside, the critics actually fail in their stylisations of what Keynes actually said. They also fail to understand the nature of the policy recommendations that Keynes was advocating.

What Keynes demonstrated was that when private demand fails during a recession and the private sector will not buy any more goods and services, then government spending interventions were necessary. He said that while hiring people to dig holes only to fill them up again would work to stimulate demand, there were much more creative and useful things that the government could do.

Keynes maintained that in a crisis caused by inadequate private willingness or ability to buy goods and services, it was the role of government to generate demand. But, he argued, merely hiring people to dig holes, while better than nothing, is not a reasonable way to do it.

In Chapter 16 of The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, Keynes wrote, in the book’s typically impenetrable style:

If – for whatever reason – the rate of interest cannot fall as fast as the marginal efficiency of capital would fall with a rate of accumulation corresponding to what the community would choose to save at a rate of interest equal to the marginal efficiency of capital in conditions of full employment, then even a diversion of the desire to hold wealth towards assets, which will in fact yield no economic fruits whatever, will increase economic well-being. In so far as millionaires find their satisfaction in building mighty mansions to contain their bodies when alive and pyramids to shelter them after death, or, repenting of their sins, erect cathedrals and endow monasteries or foreign missions, the day when abundance of capital will interfere with abundance of output may be postponed. “To dig holes in the ground,” paid for out of savings, will increase, not only employment, but the real national dividend of useful goods and services. It is not reasonable, however, that a sensible community should be content to remain dependent on such fortuitous and often wasteful mitigations when once we understand the influences upon which effective demand depends.

So while the narrative style is typical Keynes (I actually think the General Theory is a poorly written book) the message is clear. Keynes clearly understands that digging holes will stimulate aggregate demand when private investment has fallen but not increase “the real national dividend of useful goods and services”.

He also notes that once the public realise how employment is determined and the role that government can play in times of crisis they would expect government to use their net spending wisely to create useful outcomes.

Earlier, in Chapter 10 of the General Theory you read the following:

If the Treasury were to fill old bottles with banknotes, bury them at suitable depths in disused coalmines which are then filled up to the surface with town rubbish, and leave it to private enterprise on well-tried principles of laissez-faire to dig the notes up again (the right to do so being obtained, of course, by tendering for leases of the note-bearing territory), there need be no more unemployment and, with the help of the repercussions, the real income of the community, and its capital wealth also, would probably become a good deal greater than it actually is. It would, indeed, be more sensible to build houses and the like; but if there are political and practical difficulties in the way of this, the above would be better than nothing.

Again a similar theme. The government can stimulate demand in a number of ways when private spending collapses. But they should choose ways that will yield more “sensible” products such as housing. He notes too that politics might intervene in doing what is best. When that happens the sub-optimal but effective outcome would be suitable.

So the answer is false. As long as the road builder is paying on-going wages to construct, tear up and construct the road again then this will be beneficial for aggregate demand. The workers employed will spend a proportion of their weekly incomes on other goods and services which, in turn, provides wages to workers providing those outputs. They spend a proportion of this income and the “induced consumption” (induced from the initial spending on the road) multiplies throughout the economy.

This is the idea behind the expenditure multiplier.

The economy may not get much useful output from such a policy but aggregate demand would be stronger and employment higher as a consequence.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

Question 4:

The imposition of a fiscal rule at the national government level that the budget is required to be in balance at all times would eliminate budget swings driven by the automatic stabilisers.

The answer is False.

The final budget outcome is the difference between total federal revenue and total federal outlays. So if total revenue is greater than outlays, the budget is in surplus and vice versa. It is a simple matter of accounting with no theory involved. However, the budget balance is used by all and sundry to indicate the fiscal stance of the government.

So if the budget is in surplus it is often concluded that the fiscal impact of government is contractionary (withdrawing net spending) and if the budget is in deficit we say the fiscal impact expansionary (adding net spending).

Further, a rising deficit (falling surplus) is often considered to be reflecting an expansionary policy stance and vice versa. What we know is that a rising deficit may, in fact, indicate a contractionary fiscal stance – which, in turn, creates such income losses that the automatic stabilisers start driving the budget back towards (or into) deficit.

So the complication is that we cannot conclude that changes in the fiscal impact reflect discretionary policy changes. The reason for this uncertainty clearly relates to the operation of the automatic stabilisers.

To see this, the most simple model of the budget balance we might think of can be written as:

Budget Balance = Revenue – Spending = (Tax Revenue + Other Revenue) – (Welfare Payments + Other Spending)

We know that Tax Revenue and Welfare Payments move inversely with respect to each other, with the latter rising when GDP growth falls and the former rises with GDP growth. These components of the budget balance are the so-called automatic stabilisers.

In other words, without any discretionary policy changes, the budget balance will vary over the course of the business cycle. When the economy is weak – tax revenue falls and welfare payments rise and so the budget balance moves towards deficit (or an increasing deficit). When the economy is stronger – tax revenue rises and welfare payments fall and the budget balance becomes increasingly positive. Automatic stabilisers attenuate the amplitude in the business cycle by expanding the budget in a recession and contracting it in a boom.

So just because the budget goes into deficit doesn’t allow us to conclude that the Government has suddenly become of an expansionary mind. In other words, the presence of automatic stabilisers make it hard to discern whether the fiscal policy stance (chosen by the government) is contractionary or expansionary at any particular point in time.

The first point to always be clear about then is that the budget balance is not determined by the government. Its discretionary policy stance certainly is an influence but the final outcome will reflect non-government spending decisions. In other words, the concept of a fiscal rule – where the government can set a desired balance (in the case of the question – zero) and achieve that at all times is fraught.

It is likely that in attempting to achieve a balanced budget the government will set its discretionary policy settings counter to the best interests of the economy – either too contractionary or too expansionary.

If there was a balanced budget fiscal rule and private spending fell dramatically then the automatic stabilisers would push the budget into the direction of deficit. The final outcome would depend on net exports and whether the private sector was saving overall or not. Assume, that net exports were in deficit (typical case) and private saving overall was positive. Then private spending declines.

In this case, the actual budget outcome would be a deficit equal to the sum of the other two balances.

Then in attempting to apply the fiscal rule, the discretionary component of the budget would have to contract. This contraction would further reduce aggregate demand and the automatic stabilisers (loss of tax revenue and increased welfare payments) would be working against the discretionary policy choice.

In that case, the application of the fiscal rule would be undermining production and employment and probably not succeeding in getting the budget into balance.

But every time a discretionary policy change was made the impact on aggregate demand and hence production would then trigger the automatic stabilisers via the income changes to work in the opposite direction to the discretionary policy shift.

You might like to read these blogs for further information:

Question 5:

The private domestic sector can save overall even if the government deficit is in surplus as long as net exports are positive. But typically with net exports negative, the government has to run deficits to enable to private domestic sector to save overall.

The answer is True.

This is a question about the sectoral balances – the government budget balance, the external balance and the private domestic balance – that have to always add to zero because they are derived as an accounting identity from the national accounts. The balances reflect the underlying economic behaviour in each sector which is interdependent – given this is a macroeconomic system we are considering.

To refresh your memory the balances are derived as follows. The basic income-expenditure model in macroeconomics can be viewed in (at least) two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of spending; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the income produced. Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances.

From the sources perspective we write:

GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

From the uses perspective, national income (GDP) can be used for:

GDP = C + S + T

which says that GDP (income) ultimately comes back to households who consume (C), save (S) or pay taxes (T) with it once all the distributions are made.

Equating these two perspectives we get:

C + S + T = GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

So after simplification (but obeying the equation) we get the sectoral balances view of the national accounts.

(I – S) + (G – T) + (X – M) = 0

That is the three balances have to sum to zero. The sectoral balances derived are:

- The private domestic balance (I – S) – positive if in deficit, negative if in surplus.

- The Budget Deficit (G – T) – negative if in surplus, positive if in deficit.

- The Current Account balance (X – M) – positive if in surplus, negative if in deficit.

These balances are usually expressed as a per cent of GDP but that doesn’t alter the accounting rules that they sum to zero, it just means the balance to GDP ratios sum to zero.

A simplification is to add (I – S) + (X – M) and call it the non-government sector. Then you get the basic result that the government balance equals exactly $-for-$ (absolutely or as a per cent of GDP) the non-government balance (the sum of the private domestic and external balances).

This is also a basic rule derived from the national accounts and has to apply at all times.

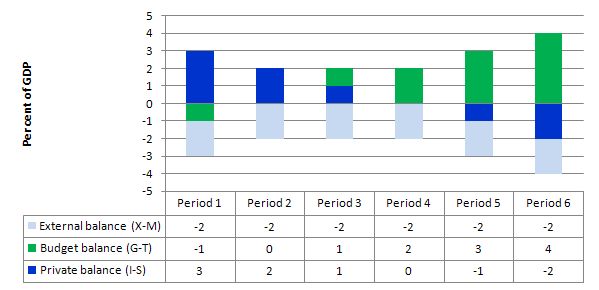

The following graph with accompanying data table lets you see the evolution of the balances expressed in terms of percent of GDP. I have held the external deficit constant at 2 per cent of GDP (which is artificial because as economic activity changes imports also rise and fall).

To aid interpretation remember that (I-S) > 0 means that the private domestic sector is spending more than they are earning; that (G-T) < 0 means that the government is running a surplus because T > G; and (X-M) < 0 means the external position is in deficit because imports are greater than exports.

In Period 1, there is an external deficit (2 per cent of GDP), a budget surplus of 1 per cent of GDP and the private sector is in deficit (I > S) to the tune of 3 per cent of GDP.

In Period 2, as the government budget enters balance (presumably the government increased spending or cut taxes or the automatic stabilisers were working), the private domestic deficit narrows and now equals the external deficit.

This provides another important rule with the Flat Earth Theorists typically overlook. That if you have an external deficit and you succeed in balancing the public budget then the private sector will be in deficit equal to the external deficit. That means, the private sector is increasingly building debt. That conclusion is inevitable when you balance a budget with an external deficit. It could never be a viable fiscal rule.

In Periods 3 and 4, the budget deficit rises from balance to 1 to 2 per cent of GDP and the private domestic balance moves towards surplus. At the end of Period 4, the private sector is spending as much as they earning.

Periods 5 and 6 show the benefits of budget deficits when there is an external deficit. The private sector now is able to generate surpluses overall (that is, save as a sector) as a result of the public deficit.

So what is the economics of this result?

If the nation is running an external deficit it means that the contribution to aggregate demand from the external sector is negative – that is net drain of spending – dragging output down.

The external deficit also means that foreigners are increasing financial claims denominated in the local currency. Given that exports represent a real cost and imports a real benefit, the motivation for a nation running a net exports surplus (the exporting nation in this case) must be to accumulate financial claims (assets) denominated in the currency of the nation running the external deficit.

A fiscal surplus also means the government is spending less than it is “earning” and that puts a drag on aggregate demand and constrains the ability of the economy to grow.

In these circumstances, for income to be stable, the private domestic sector has to spend more than they earn.

You can see this by going back to the aggregate demand relations above. For those who like simple algebra we can manipulate the aggregate demand model to see this more clearly.

Y = GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that the total national income (Y or GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

So if the G is spending less than it is “earning” and the external sector is adding less income (X) than it is absorbing spending (M), then the other spending components must be greater than total income.

Only when the government budget deficit supports aggregate demand at income levels which permit the private sector to save out of that income will the latter achieve its desired outcome. At this point, income and employment growth are maximised and private debt levels will be stable.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

Regarding question 1, I posted the following on the questions blog, shortly before seeing this answers blog:

“China runs a surplus with the US and accumulates dollar assets (reserves).

Suppose things suddenly turn around and the US runs a surplus with China. Then the US gets paid in dollars through its capital account. China runs down its dollar assets to pay for it.

Now look at Bill’s question:

“The only way that you can have unbalanced external accounts across nations (some countries with surpluses and other deficits) is because the surplus countries desire to hold financial assets denominated in the currency of the deficit countries.”

The US, a surplus country, does not end up holding Yuan assets in my example, so long as China still has a net dollar asset position.”

With follow up qualification:

“In normal circumstances, I might be accused of something approaching finagling to get my result, but Bill is sufficiently precise in his wording that I think this does not apply in this case.”

Re Q2 – I have a few things to say and my spirit is giving the benefit of the doubt to some of the central bankers. The mainstream economists misinterpreted it as the Bank of Japan lending the banks and the banks lending “out those reserves”. However, I think the Bank of Japan may have done it intentionally – knowing fully that banks neither “lend out those reserves”, nor wait for the reserves to fall from the sky. I like this line from a Cleveland Fed article

The banking system doesn’t lose the deposits but individual banks may be scared of funding problems and the Bank of Japan instead of merely promising to lend the banks at the bank rate if needed, acted in advance. In this way, banks also don’t have to worry about collateral because a movement of deposit out of a single bank just reduces its huge balance at the BoJ without any further action needed by the bank.

In the US, on the other hand, its more appropriate to call the purchases of Treasuries, agency debt and agency mortgage backed securities as Large Scale Asset Purchases. The purchases of Treasury securities may have been to bring back the amount held to the pre-crisis level. During the crisis, the Fed had to sell Treasuries in huge amounts to offset reserves created while it was acting as the lender of the last resort and targeting fed funds at 1%. The purchases of MBSs was I guess related to bringing down the mortgage rates and the US macroeconomics seems to be sensitive to the mortgage rates. The securitization market was in turmoil because of the “run on the repo” and fire-sales to satisfy collateral/haircut requirements. The Fed stepped in and eased the pressure on this market by keeping securitization alive. Moral hazard issues here, Banks are so addicted to the securitization route in the US that they would have stopped lending even if borrowers are good simply because they want to take the securitization route to “funding”. (banks’ psychology).

In the Euro Zone, the interbank markets almost freezed and the ECB lent in unlimited amounts to keep the funding going. When deposits move out of a single bank, the banks can borrow them back from another bank by providing collateral but the lender may not like the collateral. So the ECB funded them indirectly by relaxing its collateral standards.

Ahh. Anon’s point leads me to speculate that Bill’s Question 1 may be an oversimplification that doesn’t really represent what goes on in the “real world” because it does not address the Triffin dilemma. I believe that since the US dollar is more-or-less “the” global reserve currency (at this moment anyway), most trade occurs in US dollar terms and surplus countries end up owning US financial assets rather than financial assets denominated in the currency of the deficit country.

My question is this: If I rebalance the accounting identity to solve for M, I get:

I+(G-T)+X= M

I can understand the savings/investment pairing , and the government spending/taxation pairing. But I don’t understand how imports can be equal to Investment, net government spending and exports. I guess the export/import balance is still confusing me.

Hi, Bill-

I would like to differ with question 4. I agree with all your arguments in your analysis, but automatic stabilizers wouldn’t even exist if the government had a strict budget balance rule. It would seem that with such a rule, business cycles would still drive taxing and spending swings, but they could not be characterized as automatic stabilizers, since the government has robbed itself of extending such assistence to the economy, adopting what is, in essence, an inert or pro-cyclical policy. Thus the answer should be false, since while swings would take place, they would be due to a process that no longer could be called an automatic stabilizer. Automatic de-stablilizer perhaps!

Patriot,

M = (I – S) + (G – T) + X

One derivation:

Government surplus + non government surplus = 0

Government surplus + private surplus + foreign surplus = 0

(T – G) + (S – I) + (M – X) = 0

(M – X) = (G – T) + (I – S)

M = (G – T) + (I – S) + X

Moving away from the Talmudic disputations about the Balance of Payments, the domestic private sector consists of households who are the ones that save. The business sector incurs equity and bond liabilities, and an increase of these corresponds to a real increase in savings by the household sector. This does not require deficits run by either the foreign or government sector, and is the dominant source of wealth and income for the private sector.

To not count an increase in the capital stock as constituting an increase in private sector savings requires that the liabilities of the firm net out against the households that hold those liabilities while simultaneously not allow the liabilities of the firm to net out against the actual capital stock of the firm.

That is a bizarre and non-economic interpretation of “save overall”. You should have stuck with the mantra “net financial assets”, at which point the answer would be “true, but misleading”. The economy is driven by changes in the capital stock as well as changes in the perceived future earnings of that capital stock, together with real balance effects. These dynamics — what happens within the private sector — are not captured when you zero-out the entire nation’s business sector and assume that an increase in productive assets, or in the perceived earnings power of these assets, contributes nothing to an increase in private sector assets “overall”.

I agree that the “save overall” terminology is ambiguous, if not misleading or wrong.

MMT tends to slip into generic “save” terminology, within its own paradigm. This is understandable, given normal MMT context, and the natural desirability of avoiding repetition. But the paradigm is based on concepts of “net save”, “net financial assets”, and “sector financial balances”. All of that financial netting at the macro level starts from the conventional concept of national accounts saving and investment. That should not be forgotten. And it should not be omitted too often, particularly given the interest of newer readers or those who may not assume the normal MMT net financial context of the discussion.

That said above, the question (#5) does provide the context of sector balances, so the net save, net financial asset meaning might have been inferred. That’s what I did.

Right, but the issue now is how much economic insight is lost when you focus on net savings across the entire private sector?

No household measures savings this way, and no household’s spending decisions are driven by these concerns. Same for the business sector. And taken together, these are the actors that largely determine output and employment.

Can you really argue that the sole source of unemployment is insufficient deficit spending to the private sector as a whole? We had lower unemployment levels when we deficit spent less in the 1950-1980 period.

How far can your analysis take you when the balance sheets that you are measuring are consolidated across both firms and households? Or across both debtor and creditor households. 4/5 of households have negative net financial financial assets.

The consolidation should be limited to broad groups of actors within the private sector — e.g. at least look at the household, non-financial business, and financial business sector in your models. Even better, disaggregate a bit further and consolidate the balance sheet of upper and lower income brackets within the household sector, and distinguish between industrial goods-producing firms (with falling unit costs and excess capacity) and service sector firms (for which there is no measure of excess capacity).

That requires a lot more work, of course, but it paints a more accurate picture, and can often reverse the conclusions that are reached when balance sheets are consolidated across the entire private sector. That would require a fundamental change to MMT — in my view, a positive change.

I agree insight is lost.

MMT is a pretty simple macro strategy. It basically assumes a failure in the economic system’s ability to generate sufficient macro saving via macro investment, with the government taking up the slack by generating “net saving”. It doesn’t investigate the cause or resolution of macro investment-generated saving as a first priority.

MMT sometimes refers to the private sector’s desire for net saving. That’s not really accurate. The private sector desires a certain level of saving – not net saving specifically. Net saving takes up the slack when investment generated saving fails to satisfy the demand for saving.

Yes, so why can’t we have a macro-theory that combines a reasonable understanding of inter-sectoral balances with a reasonable model of the private sector — a model that can diagnose why the source of the breakdown occurred as well as prescribe the best fixes so that the private sector can again generate demand endogenously?

Or is there a panglossian view of the private sector fixing itself with enough government income support? Wont the income support allow the forces that generated the breakdown to continue?

And why can’t the various proposals — such as the no bonds proposal — be based on a strong case that they would improve the functioning of the private sector, rather than resorting to arguments about what is “natural”?

Guns & Butter interview with Michael Hudson in full flight on ‘Europe’s Financial Class War Against Labor, Industry and Government’ (also noticed PoBC has announced a currency float):

Economic crisis in Europe created by predatory lending; European Central Bank stranglehold on the Eurozone; the Euro; foreign banks decimate Greece’s social structure; Marx’s industrial capital versus fictitious capital; Latvia as a model for the rest of Europe; Hudson’s financial and fiscal plan for Latvia; the Cold War and its ruinous effect on progressive economic thought.

Like MMT on steroids!!! …. scary stuff. http://aud1.kpfa.org/data/20100616-Wed1300.mp3

Dear Patriot (at 2010/06/20 at 4:02)

What happened to private domestic saving?

best wishes

bill

Dear Burk (at 2010/06/20 at 4:37)

The balanced budget rule does not eliminate the stabilisers. You would have to make taxation independent of income and no payments that rely on the level of economic activity to eliminate the stabilisers.

best wishes

bill

Bill –

Your solution to question 1 doesn’t adequately take the option of sovereign debt into account. As I said yesterday, I think that affects the answer.

I agree with your answer to question 2, but your solution is exceedingly convoluted. A much simpler explanation supply and demand. Like everything else, increasing the supply decreases the value but increasing demand increases value, so putting more money in the economy only results in its value declining if demand for it doesn’t rise at the same rate or faster.

And I dispute your claim that when we talk about quantitative easing, we must first understand that it requires the short-term interest rate to be at zero or close to it. Otherwise, the central bank would not be able to maintain control of a positive interest rate target because the excess reserves would invoke a competitive process in the interbank market which would effectively drive the interest rate down.

Unless the interest rate is near zero, it’s unlikely that quantitative easing would be seen as a sensible option. However if the central bank did go with it, there’s no reason why they’d lose control of the interest rates. It would merely have the same effect as reducing the interest rate.

>So, on balance, if a nation can persuade foreigners to send more ships filled with things than it has to send in return (net export deficit) then that is a net benefit to the local economy.

This seems a little counter intuitive to me, because although you may not have to “produce” anything, you no longer have control of the supply which could be disruptive to your economy.

Oil is a example where fluctuations in supply and price can be very disruptive to the local economy. It may not “cost” the economy in a “production” sense, but it is an outside input to the economy that can fluctuate outside the governments control.

Do you think we should shut down all of our local oil production and just let foreigners send more ships ?? I suspect this would be a pretty bad idea. Simply focusing on the finances of a nation via “production” seems limited, surely stability needs to be somewhere in the equation as well.

As a countervailing view to the “ships supplied with stuff” mental model, I would say that many of the old-school economists — and here I would even put Marshall — made a distinction between increasing return to scale industries and diminishing return to scale industries.

They focused on production “eco-systems”, replete with institutional knowledge, infrastructure, networks of suppliers and producers, investors who understood how to assess industries, relationships between creditors and borrowers, social networks of skilled workers, and generally a pool of expertise and talent.

These production eco-systems were valued, and contributed to the wealth and well-being of the nation. Loss of these eco-systems meant that the nation suffered a net harm.

This is a completely different view of the perfectly elastic production model in which the government can add currency and supply the domestic population with enough funds to buy Chinese goods, for example. The loss of engineering and manufacturing jobs is considered a blow to well-being and to long term consumption opportunities.

This is not to say that China is not harming itself by orienting its economy around exports. It will be very painful for China to adjust so that its industry is able to make things that the domestic population wants, at prices that they can afford to pay.

But it will be equally hard for the west to adjust as well.

In both cases, the nations involved in propagating these imbalances are suffering a net harm.

It requires a somewhat different view of economics to see that.

One that does not just look at immediate-term consumption of final output, but long term well-being and long term sustainable production and consumption. Both need to be valued and cultivated. Both are delicate ecosystems of knowledge, institutions, relationships and prices.

“Living in Australia (one of the World’s largest primary commodity exporters) I am always bemused by the notion that digging holes and filling them up again is futile work. It seems to characterise our mining sector very well.”

Excellent. Great laugh in the morning, thanks.

A model can easily be made by disaggregating the private sector into households, producers, and the financial sector. The household receives income through wages, interest payments, dividends. It consumes a fraction (big?) of the income and a small part of the wealth. The constants of proportionality are the propensity to consume out of income and wealth. The rest is saved – allocated in financial assets. The other sectors make their decisions. The net saving or the income less expenditures is decided by these parameters. The fiscal numbers – the government income less expenditure i.e., taxes less spending adjusts so that the identities are satisfied.

On the other hand, as far as the external sector is concerned, the current account deficit which is mainly exports less imports is due to the decisions of households/residents to choose imported goods over domestically produced goods – their propensity to import versus the demand of their produced goods in the rest of the world. The saving of the rest of the world is decided by this rather than the saving desire of the rest of the world. It is determined by relative competitiveness. Of course, with some countries pegging their exchange rates to low values, the phrase “competitiveness” is not the correct phrase.

If the US manufactures get inspired by the craze for Apple’s iPhone 4, and manage to make attractive products, or for some reason, the there is an invention revolution in the US, the demand for US products in the rest of the world will increase and the trade deficit may turn into a surplus. The rest of the world cannot do much.

correction – should read imports less exports in the second para.

Ramanan,

There shouldn’t be anything particularly unique about the current account when it comes to the net saving concept.

MMT would say the Chinese surplus in dollars is due to the desire of China to net save in dollars (through its current account). How could this not be a truism? China would rather have dollars than imports.

The idea of net saving desire is completely fungible. If I borrow from the bank to spend, and my neighbour ends up with the deposit that’s been created, then I’m net saving and the neighbour is net dissaving. That’s no different in net saving concept than if I borrow to spend on Chinese imports and China ends up with my dollars.

meant above:

“I’m net dissaving and the neighbour is net saving”

Anon,

True about your example. However, if you include the rest of the world, the US consumer has a choice. He/she can buy a domestically manufactured product or an import. If the purchase is domestic, China saves lesser than what it would have. The choice depends on many things like price etc, but in the end, the US producer has lost something.

The US and the Chinese manufactures’s positions are different. The US household sector works for the US manufacturing sector and gets wages from it. If the Chinese goods are purchased, the US manufacturer will manufacture less and it leads to lesser income for the US household and hence reduced employment. The fact that imports reduce aggregate demand can also be seen in other ways.

The two manufacturers have no control over the amount of sales – that is decided by the incomes of the household sector. The proportion that the household decides to buy based on various factors and the competition decides.

If we talk of just a closed economy, there is a quantity the private sector is targeting. The producers sector is typically a deficit spending unit but since it has produced fixed capital and has a stock of inventories its okay for it to be deficit spending. It still has a positive net worth. The household sector on the other hand, typically is the surplus spending sector. It can be said to be saving or may be looked at as targeting a wealth. The producer sector is anyway a deficit spending unit and is not saving. So the private sector propensity to save is basically the household sectors’ propensity.

On the other hand, when we talk of the foreign sector, we are talking of the foreign production sector which is a deficit spending unit. It has no control over the sales, because purchases of its products is a demand dependent phenomenon. It can improve its sales by being more competitive, but unlike the US household, it cannot have a target.

Ramanan said:

“The US and the Chinese manufactures’s positions are different. The US household sector works for the US manufacturing sector and gets wages from it. If the Chinese goods are purchased, the US manufacturer will manufacture less and it leads to lesser income for the US household and hence reduced employment. The fact that imports reduce aggregate demand can also be seen in other ways. ”

So this suggests once again that importing is a bad idea, because it leads to lower employment. Yet as I said above bill said

“So, on balance, if a nation can persuade foreigners to send more ships filled with things than it has to send in return (net export deficit) then that is a net benefit to the local economy.”

This again suggest to me that there is something wrong with this statement, or is this simply a case that the people who are unemployed due to importation are then free to do some other work within the domestic economy ? Surely there is a balance here.

If the government is attempting to balance productivity, employment and economic stability then it would seem that simply turning off domestic suppy because someone accepts your vouchers in return for goods would in some way be counter productive.

Households have no choice to buy Chinese goods or not — this is controlled by the firms, who choose to outsource production to China or not. The firms are the customers with the choice of where to source production, and households have the choice of which branded good they prefer to buy. There is monopolistic competition.

This is different form the situation of buying a Japanese car or an American car. In this case, households have the choice.

This is why the U.S. chamber of commerce led a pro-China trade campaign, and an anti-Japan trade campaign. In one case, households had more choice to buy Japanese goods, but in the other case, households continued to buy U.S. goods that were manufactured elsewhere.

Again, distinctions are important here — the effects on welfare of a trade deficit with Japan is different from a trade deficit with China. One increases household incomes whereas the other decreases them. One leads to an increase in consumption whereas the other leads to a substitution of consumption. Trade competition with high wage nations tends to increase the wages paid in the industry, whereas competition with low wage nations decreases the wages paid. One leads to an increase in consumption due to economies of scale and network effects, whereas the other substitutes consumption but does not increase it.

In the case of outsourcing, you are not consuming more — manufacturing has merely shifted, exchanging domestic for foreign production. Such a situation does not increase aggregate consumption. Whether or not aggregate consumption increases (or decreases) is determined by what happens to the freed resources — do they lie idle, are they able to obtain only part-time work, or are they fully used elsewhere? And more importantly, what are the long term effects for domestic consumption?

Finally, again this topic assumes that there is no value to production in determining quality of life or what economists should target. Supposedly they should only target consumption. This assumes that if we replace engineers with walmart greeters who can still (temporarily) afford the products that the engineers used to buy, that we are not suffering in terms of quality of life. This is a view of labor that assumes people hate to produce and gain no pleasure from making.

But production is a satisfaction of wants and needs just as much as consumption. And the government should aim its policies to optimizing the quality and opportunities of both production and consumption available to it people.

In terms of savings desires, the private sector savings “desires” is an amorphous concept at best.

It is not the same as the household sector savings desire.

A household can borrow to buy a house, or a firm can borrow to expand capacity. In both cases, neither the household nor the firm views itself as having negative “savings” because they are accumulating tangible assets at an indifference level to the financial short position incurred, and yet this dissaving funds financial savings for other households and firms. All of that disappears when you look at only the financial assets of the private sector overall.

I think it is difficult to have an economically useful concept of private sector savings desires. First, you have no way of measuring this. You can measure the cost of capital of firms, and you can measure propensities to consume of households, but you cannot measure private sector savings desires.

Certainly you can argue that running surpluses is harmful and that some level of deficits must be run. But beyond that — i.e. beyond determining the sign of the deficit, you cannot say much more.

Why did the Japanese private sector suddenly need such “savings”? How much is enough?

Currently, U.S. corporations have recovered their after-tax profit levels — to about 6% of GDP — which were already elevated from the 4% average from the 1970-1990 period — and yet still unemployment is near 10%. Do they need 8%? 12%?

Corporate profits account for 31% of GDP in China, and yet still there is high unemployment, and the national income, according to the government, must grow at 8% to maintain employment, even though the population is stabilizing.

In Japan, output is beginning to rise (in real terms), but deflation is increasing as is unemployment, even though the domestic sector there continues to receive massive infusions of external income from the foreign and government sector.

The economically important movements are within the private sector, and within income cohorts of households. These internal shifts will determine whether the private sector as whole appears to need extra income or not. And of course there is no a priori reason to believe that an injection of external income will increase employment — it may simply result in re-enforcing and entrenching the price and power imbalances that caused the income shortfall to occur.

“It can improve its sales by being more competitive, but unlike the US household, it cannot have a target.”

Hmm, so I guess Japan, China, and none of these nations have a target, or manage their capital accounts in order to achieve a target.

I think a more useful concept is to talk about the process by which individual actors set their targets. Firms have externally imposed cost of capital targets. When the returns are too low, the firm liquidates capital (as well as labor), and eventually that cost of capital is lowered. When the return is too high, equity owners receive the surplus, encourage additional investment, and eventually the cost of capital is increased. That is how you get into a situation of profitable firms nevertheless shuttering capital expansion plans even though the same firm, if it were operating 30 years ago, would be more than happy with the return prospects and would expand. The bar gets raised based on expectations of previous profits — or, if you prefer, “savings”.

As a result — over time — if there is excess debt growth or other unsustainable income injected (for example, enlarged export or government income) — then the cost of capital continues to drift upwards and the economy becomes more fragile. In this way, corporate earnings drift from 20% of GDP to 30% in China — the target moves, rising upward as more external income is provided. It’s an interesting dynamic.

Bill,

Thanks, I see that it should be (I-S)+(G-T)+X = M. This is what happens when I don’t check my work.

Anon at 5:58,

Thanks, once I look at the X-M function as just a “breakout” of the non-governmental sector, it all makes sense. This is why the math is important!