Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

Saturday Quiz – July 10, 2010 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for yesterday’s quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of modern monetary theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

A budget deficit that is equivalent to 5 per cent of GDP always signals a more expansionary fiscal intent from government than a budget deficit outcome that is equivalent to 3 per cent of GDP.

The answer is False.

If I had left the “always” out of the question then the answer would have been Maybe. The inclusion of that more strict requirement (always) renders the proposition false.

The question probes an understanding of the forces (components) that drive the budget balance that is reported by government agencies at various points in time.

In outright terms, a budget deficit that is equivalent to 5 per cent of GDP is more expansionary than a budget deficit outcome that is equivalent to 3 per cent of GDP. But that is not what the question asked. The question asked whether that signalled a more expansionary fiscal intent from government.

In other words, what does the budget outcome signal about the discretionary fiscal stance adopted by the government.

To see the difference between these statements we have to explore the issue of decomposing the observed budget balance into the discretionary (now called structural) and cyclical components. The latter component is driven by the automatic stabilisers that are in-built into the budget process.

The federal (or national) government budget balance is the difference between total federal revenue and total federal outlays. So if total revenue is greater than outlays, the budget is in surplus and vice versa. It is a simple matter of accounting with no theory involved. However, the budget balance is used by all and sundry to indicate the fiscal stance of the government.

So if the budget is in surplus it is often concluded that the fiscal impact of government is contractionary (withdrawing net spending) and if the budget is in deficit we say the fiscal impact expansionary (adding net spending).

Further, a rising deficit (falling surplus) is often considered to be reflecting an expansionary policy stance and vice versa. What we know is that a rising deficit may, in fact, indicate a contractionary fiscal stance – which, in turn, creates such income losses that the automatic stabilisers start driving the budget back towards (or into) deficit.

So the complication is that we cannot conclude that changes in the fiscal impact reflect discretionary policy changes. The reason for this uncertainty clearly relates to the operation of the automatic stabilisers.

To see this, the most simple model of the budget balance we might think of can be written as:

Budget Balance = Revenue – Spending.

Budget Balance = (Tax Revenue + Other Revenue) – (Welfare Payments + Other Spending)

We know that Tax Revenue and Welfare Payments move inversely with respect to each other, with the latter rising when GDP growth falls and the former rises with GDP growth. These components of the budget balance are the so-called automatic stabilisers.

In other words, without any discretionary policy changes, the budget balance will vary over the course of the business cycle. When the economy is weak – tax revenue falls and welfare payments rise and so the budget balance moves towards deficit (or an increasing deficit). When the economy is stronger – tax revenue rises and welfare payments fall and the budget balance becomes increasingly positive. Automatic stabilisers attenuate the amplitude in the business cycle by expanding the budget in a recession and contracting it in a boom.

So just because the budget goes into deficit or the deficit increases as a proportion of GDP doesn’t allow us to conclude that the Government has suddenly become of an expansionary mind. In other words, the presence of automatic stabilisers make it hard to discern whether the fiscal policy stance (chosen by the government) is contractionary or expansionary at any particular point in time.

To overcome this uncertainty, economists devised what used to be called the Full Employment or High Employment Budget. In more recent times, this concept is now called the Structural Balance. The change in nomenclature is very telling because it occurred over the period that neo-liberal governments began to abandon their commitments to maintaining full employment and instead decided to use unemployment as a policy tool to discipline inflation.

The Full Employment Budget Balance was a hypothetical construct of the budget balance that would be realised if the economy was operating at potential or full employment. In other words, calibrating the budget position (and the underlying budget parameters) against some fixed point (full capacity) eliminated the cyclical component – the swings in activity around full employment.

So a full employment budget would be balanced if total outlays and total revenue were equal when the economy was operating at total capacity. If the budget was in surplus at full capacity, then we would conclude that the discretionary structure of the budget was contractionary and vice versa if the budget was in deficit at full capacity.

The calculation of the structural deficit spawned a bit of an industry in the past with lots of complex issues relating to adjustments for inflation, terms of trade effects, changes in interest rates and more.

Much of the debate centred on how to compute the unobserved full employment point in the economy. There were a plethora of methods used in the period of true full employment in the 1960s. All of them had issues but like all empirical work – it was a dirty science – relying on assumptions and simplifications. But that is the nature of the applied economist’s life.

As I explain in the blogs cited below, the measurement issues have a long history and current techniques and frameworks based on the concept of the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (the NAIRU) bias the resulting analysis such that actual discretionary positions which are contractionary are seen as being less so and expansionary positions are seen as being more expansionary.

The result is that modern depictions of the structural deficit systematically understate the degree of discretionary contraction coming from fiscal policy.

So the data provided by the question could indicate a more expansionary fiscal intent from government but it could also indicate a large automatic stabiliser (cyclical) component.

Therefore the best answer is false because there are circumstances where the proposition will not hold. It doesn’t always hold.

You might like to read these blogs for further information:

Question 2:

Government spending which is accompanied by a bond sale to the private sector adds less to aggregate demand than would be the case if there was no bond sale.

The answer is false.

The mainstream macroeconomic textbooks all have a chapter on fiscal policy (and it is often written in the context of the so-called IS-LM model but not always).

The chapters always introduces the so-called Government Budget Constraint that alleges that governments have to “finance” all spending either through taxation; debt-issuance; or money creation. The writer fails to understand that government spending is performed in the same way irrespective of the accompanying monetary operations.

The textbook argument claims that money creation (borrowing from central bank) is inflationary while the latter (private bond sales) is less so. These conclusions are based on their erroneous claim that “money creation” adds more to aggregate demand than bond sales, because the latter forces up interest rates which crowd out some private spending.

All these claims are without foundation in a fiat monetary system and an understanding of the banking operations that occur when governments spend and issue debt helps to show why.

So what would happen if a sovereign, currency-issuing government (with a flexible exchange rate) ran a budget deficit without issuing debt?

Like all government spending, the Treasury would credit the reserve accounts held by the commercial bank at the central bank. The commercial bank in question would be where the target of the spending had an account. So the commercial bank’s assets rise and its liabilities also increase because a deposit would be made.

The transactions are clear: The commercial bank’s assets rise and its liabilities also increase because a new deposit has been made.

Further, the target of the fiscal initiative enjoys increased assets (bank deposit) and net worth (a liability/equity entry on their balance sheet).

Taxation does the opposite and so a deficit (spending greater than taxation) means that reserves increase and private net worth increases.

This means that there are likely to be excess reserves in the “cash system” which then raises issues for the central bank about its liquidity management. The aim of the central bank is to “hit” a target interest rate and so it has to ensure that competitive forces in the interbank market do not compromise that target.

When there are excess reserves there is downward pressure on the overnight interest rate (as banks scurry to seek interest-earning opportunities), the central bank then has to sell government bonds to the banks to soak the excess up and maintain liquidity at a level consistent with the target.

Some central banks offer a return on overnight reserves which reduces the need to sell debt as a liquidity management operation.

There is no sense that these debt sales have anything to do with “financing” government net spending. The sales are a monetary operation aimed at interest-rate maintenance.

So M1 (deposits in the non-government sector) rise as a result of the deficit without a corresponding increase in liabilities. It is this result that leads to the conclusion that that deficits increase net financial assets in the non-government sector.

What would happen if there were bond sales? All that happens is that the banks reserves are reduced by the bond sales but this does not reduce the deposits created by the net spending. So net worth is not altered. What is changed is the composition of the asset portfolio held in the non-government sector.

The only difference between the Treasury “borrowing from the central bank” and issuing debt to the private sector is that the central bank has to use different operations to pursue its policy interest rate target. If it debt is not issued to match the deficit then it has to either pay interest on excess reserves (which most central banks are doing now anyway) or let the target rate fall to zero (the Japan solution).

There is no difference to the impact of the deficits on net worth in the non-government sector.

Mainstream economists would say that by draining the reserves, the central bank has reduced the ability of banks to lend which then, via the money multiplier, expands the money supply.

However, the reality is that:

- Building bank reserves does not increase the ability of the banks to lend.

- The money multiplier process so loved by the mainstream does not describe the way in which banks make loans.

- Inflation is caused by aggregate demand growing faster than real output capacity. The reserve position of the banks is not functionally related with that process.

So the banks are able to create as much credit as they can find credit-worthy customers to hold irrespective of the operations that accompany government net spending.

This doesn’t lead to the conclusion that deficits do not carry an inflation risk. All components of aggregate demand carry an inflation risk if they become excessive, which can only be defined in terms of the relation between spending and productive capacity.

It is totally fallacious to think that private placement of debt reduces the inflation risk. It does not.

You may wish to read the following blogs for more information:

- Why history matters

- Building bank reserves will not expand credit

- Building bank reserves is not inflationary

- The complacent students sit and listen to some of that

Question 3:

If the external balance is always in surplus, then the government can safely run a surplus and not impede economic growth. However, this option is only available to a few nations because not all nations can run external surpluses.

The answer is false.

I noted several questions in the comments section about this particular problem. The secret to understanding the answer is two-fold.

First, you need to understand the basic relationship between the sectoral flows and the balances that are derived from them. The flows are derived from the National Accounting relationship between aggregate spending and income. So:

(1) Y = C + I + G + (X – M)

where Y is GDP (income), C is consumption spending, I is investment spending, G is government spending, X is exports and M is imports (so X – M = net exports).

Another perspective on the national income accounting is to note that households can use total income (Y) for the following uses:

(2) Y = C + S + T

where S is total saving and T is total taxation (the other variables are as previously defined).

You than then bring the two perspectives together (because they are both just “views” of Y) to write:

(3) C + S + T = Y = C + I + G + (X – M)

You can then drop the C (common on both sides) and you get:

(4) S + T = I + G + (X – M)

Then you can convert this into the familiar sectoral balances accounting relations which allow us to understand the influence of fiscal policy over private sector indebtedness.

So we can re-arrange Equation (4) to get the accounting identity for the three sectoral balances – private domestic, government budget and external:

(S – I) = (G – T) + (X – M)

The sectoral balances equation says that total private savings (S) minus private investment (I) has to equal the public deficit (spending, G minus taxes, T) plus net exports (exports (X) minus imports (M)), where net exports represent the net savings of non-residents.

Another way of saying this is that total private savings (S) is equal to private investment (I) plus the public deficit (spending, G minus taxes, T) plus net exports (exports (X) minus imports (M)), where net exports represent the net savings of non-residents.

All these relationships (equations) hold as a matter of accounting and not matters of opinion.

Thus, when an external deficit (X – M < 0) and public surplus (G - T < 0) coincide, there must be a private deficit. While private spending can persist for a time under these conditions using the net savings of the external sector, the private sector becomes increasingly indebted in the process.

Second, you then have to appreciate the relative sizes of these balances to answer the question correctly.

Consider the following Table which depicts three cases - two that define a state of macroeconomic equilibrium (where aggregate demand equals income and firms have no incentive to change output) and one (Case 2) where the economy is in a disequilibrium state and income changes would occur.

Note that in the equilibrium cases, the (S - I) = (G - T) + (X - M) whereas in the disequilibrium case (S - I) > (G - T) + (X - M) meaning that aggregate demand is falling and a spending gap is opening up. Firms respond to that gap by decreasing output and income and this brings about an adjustment in the balances until they are back in equality.

So in Case 1, assume that the private domestic sector desires to save 2 per cent of GDP overall (spend less than they earn) and the external sector is running a surplus equal to 4 per cent of GDP.

In that case, aggregate demand will be unchanged if the government runs a surplus of 2 per cent of GDP (noting a negative sign on the government balance means T > G).

In this situation, the surplus does not undermine economic growth because the injections into the spending stream (NX) are exactly offset by the leakages in the form of the private saving and the budget surplus. This is the Norwegian situation.

In Case 2, we hypothesise that the private domestic sector now wants to save 6 per cent of GDP and they translate this intention into action by cutting back consumption (and perhaps investment) spending.

Clearly, aggregate demand now falls by 4 per cent of GDP and if the government tried to maintain that surplus of 2 per cent of GDP, the spending gap would start driving GDP downwards.

The falling income would not only reduce the capacity of the private sector to save but would also push the budget balance towards deficit via the automatic stabilisers. It would also push the external surplus up as imports fell. Eventually the income adjustments would restore the balances but with lower GDP overall.

So Case 2 is a not a position of rest – or steady growth. It is one where the government sector (for a given net exports position) is undermining the changing intentions of the private sector to increase their overall saving.

In Case 3, you see the result of the government sector accommodating that rising desire to save by the private sector by running a deficit of 2 per cent of GDP.

So the injections into the spending stream are 4 per cent from NX and 2 per cent from the deficit which exactly offset the desire of the private sector to save 6 per cent of GDP. At that point, the system would be in rest.

This is a highly stylised example and you could tell a myriad of stories that would be different in description but none that could alter the basic point.

If the drain on spending outweighs the injections into the spending stream then GDP falls (or growth is reduced).

So even though an external surplus is being run, the desired budget balance still depends on the saving desires of the private domestic sector. Under some situations, these desires could require a deficit even with an external surplus.

You may wish to read the following blogs for more information:

- Stock-flow consistent macro models

- Norway and sectoral balances

- The OECD is at it again!

- Barnaby, better to walk before we run

- Saturday Quiz – June 19, 2010 – answers and discussion

Question 4:

Assume the current public debt to GDP ratio is 100 per cent and that the nominal interest rate and the inflation rate remain constant and zero. Under these circumstances it is impossible to reduce a public debt to GDP ratio, using an austerity package if the rise in the primary surplus to GDP ratio is always exactly offset by negative GDP growth rate of the same percentage value.

The answer is True.

This question plays on the first but investigates a difference aspect of the framework outlined above.

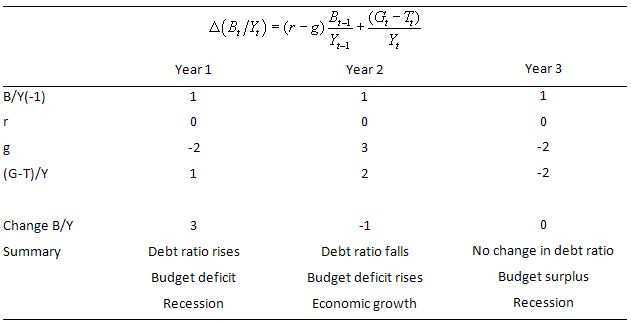

The following Table adds another year to the analysis presented above. You can see that there is a recession being encountered with negative GDP growth of 2 per cent (this is also a decline in real GDP because the inflation rate is zero).

Now the government responds to the deficit terrorists and tries to reduce the public debt ratio by running a primary budget surplus of 2 per cent of GDP – it is a negative sign in the table because the construction is (G – T)/GDP which means a surplus is a negative number.

From the formula, the change in the public debt ratio is zero.

As long as the primary surplus as a per cent of GDP is exactly equal to the negative GDP growth rate, there can be no reduction in the public debt ratio.

Of-course, this strategy, which is being pushed onto governments by the conservatives now will likely have to consequences.

First, it will probably push the GDP growth rate further into negative territory which, other things equal, pushes the public debt ratio up.

Second, as GDP growth declines further, the automatic stabilisers will push the balance result towards (and into after a time) deficit, which, given the borrowing rules that governments voluntarily enforce on themselves, also pushed the public debt ratio up.

So austerity packages, quite apart from their highly destructive impacts on real standards of living and social standards, typically fail to reduce public debt ratios and usually increase them.

So even if you were a conservative and erroneously believed that high public debt ratios were the devil’s work, it would be foolish (counter-productive) to impose fiscal austerity on a nation as a way of addressing your paranoia. Better to grit your teeth and advocate higher deficits and higher real GDP growth.

That strategy would also be the only one advocated by MMT.

The following blog may be of further interest to you:

Question 5:

The latest Australian Bureau of Statistics data shows that total hours worked in June 2010 fell while part-time employment (and total employment) grew. Unemployment stayed more or less constant. This signals rising underemployment.

The answer is Maybe.

If you didn’t get this correct then it is likely you lack an understanding of the labour force framework which is used by all national statistical offices.

The labour force framework is the foundation for cross-country comparisons of labour market data. The framework is made operational through the International Labour Organization (ILO) and its International Conference of Labour Statisticians (ICLS). These conferences and expert meetings develop the guidelines or norms for implementing the labour force framework and generating the national labour force data.

The rules contained within the labour force framework generally have the following features:

- an activity principle, which is used to classify the population into one of the three basic categories in the labour force framework;

- a set of priority rules, which ensure that each person is classified into only one of the three basic categories in the labour force framework; and

- a short reference period to reflect the labour supply situation at a specified moment in time.

The system of priority rules are applied such that labour force activities take precedence over non-labour force activities and working or having a job (employment) takes precedence over looking for work (unemployment). Also, as with most statistical measurements of activity, employment in the informal sectors, or black-market economy, is outside the scope of activity measures.

Paid activities take precedence over unpaid activities such that for example ‘persons who were keeping house’ as used in Australia, on an unpaid basis are classified as not in the labour force while those who receive pay for this activity are in the labour force as employed.

Similarly persons who undertake unpaid voluntary work are not in the labour force, even though their activities may be similar to those undertaken by the employed. The category of ‘permanently unable to work’ as used in Australia also means a classification as not in the labour force even though there is evidence to suggest that increasing ‘disability’ rates in some countries merely reflect an attempt to disguise the unemployment problem.

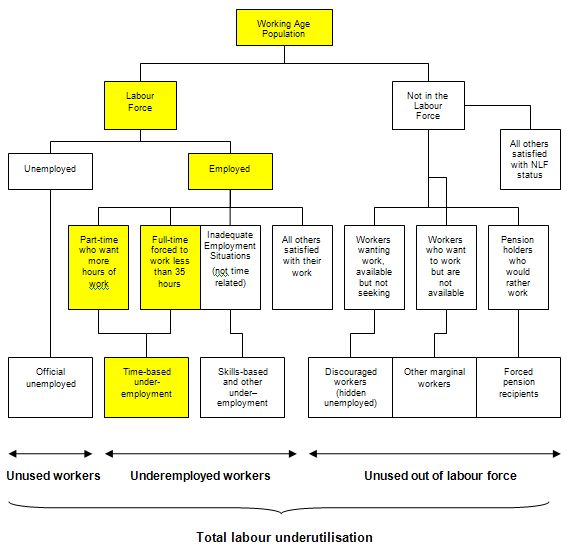

Labour underutilisation

Underutilisation is a general term describing the wastage of willing labour resources. It arises from a number of different reasons that can be subdivided into two broad functional categories:

- A category involving unemployment or its near equivalent. In this group, we include the official unemployed under ILO criteria and those classified as being not in the labour force on search criteria (discouraged workers), availability criteria (other marginal workers), and more broad still, those who take disability and other pensions as an alternative to unemployment (forced pension recipients). These workers share the characteristic that they are jobless and desire work if there were available vacancies. They are however separated by the statistician on other grounds.

- A category that involves sub-optimal employment relations. Workers in this category satisfy the ILO criteria for being classified as employed but suffer time-related underemployment – for example, full-time workers who are currently working less than 35 hours for economic reasons or part-time workers who prefer to work longer hours but are constrained by the demand-side. Sub-optimal employment can also arise from inadequate employment situations – where skills are wasted, income opportunities denied and/or where workers are forced to work longer than they desire.

Time-related and other types of underemployment

Underemployment may be time-related, referring to employed workers who are constrained by the demand side of the labour market to work fewer hours than they desire, or to workers in inadequate employment situations, including for example, skill mismatch.

Clearly, if society invests resources in education, then the skills developed should be used appropriately. This latter category of underemployment is however, very difficult to quantify. For the purposes of this question I assumed that we were only discussing time-based underemployment.

In conceptual terms, a part of an underemployed worker is employed and a part is unemployed, even though they are wholly classified among the employed.

Time-related underemployment is defined in terms of a willingness to work additional hours, an availability to work additional hours, and having worked less than a threshold relating to working time. In Australia, in line with the standard measurement of unemployment, persons actively seeking additional hours of work are distinguished from those who are not.

Reflecting changing employment relationships and an increase in multiple job-holding, in Australia the questions collecting underemployment information reflect a wider range of situations where people are seeking to work more hours. This is in line with the standard international practice.

Two main reasons for time-related underemployment are identified:

- Part-time workers wanting more hours of work;

- Full-time workers who worked less than 35 hours in the reference week for economic reasons (stood down or insufficient work).

The following diagram shows the complete breakdown of the categories used by the statisticians in this context. The yellow boxes are relevant for this question.

So the Working Age Population (WAP) is usually defined as those persons aged between 15 and 65 years of age or increasing those persons above 15 years of age (recognising that official retirement ages are now being abandoned in many countries).

As you can see from the diagram the WAP is then split into two categories: (a) the Labour Force (LF) and; (b) Not in the Labour Force – and this division is based on activity tests (being in paid employed or actively seeking and being willing to work).

The Labour Force Participation Rate is the percentage of the WAP that are active.

You can also see that the Labour Force is divided into employment and unemployment. Most nations use the standard demarcation rule that if you have worked for one or more hours a week during the survey week you are classified as being employed.

If you are not working but indicate you are actively seeking work and are willing to currently work then you are considered to be unemployed.

If you are not working and indicate either you are not actively seeking work or are not willing to work currently then you are considered to be

Not in the Labour Force.

So you get the category of hidden unemployed who are willing to work but have given up looking because there are no jobs available. The statistician counts them as being outside the labour force even though they would accept a job immediately if offered.

Now trace through the yellow boxes which are linked by the following formulas:

Labour Force = Employment + Unemployment = Labour Force Participation Rate times the Working Age Population

It follows that the Working Age Population is derived as Labour Force divided by the Labour Force Participation Rate (appropriately scaled in percentage point units).

Employment is then divided into four sub-categories:

- Part-time who want more hours of work

- Full-time forced to work less than 35 hours per week

- Inadequate employment situations (not time-related)

- All others satisfied with their work

Underemployment thus relates to 3 of these employment categories but time-related underemployment relates to the first two (yellow) categories.

The question tells you that total working hours fell in June 2010 but part-time employment (and total employment) grew. This information would signal rising underemployment if:

- The extra part-time workers or a rising proportion of them were unhappy with the hours of work they were offered.

- If the growth in part-time work was, in part, the result of full-time workers forced to work less than 35 hours per week.

So the best answer it maybe. When the ABS publishes the relevant data in the August quarter we will know the truth.

You may wish to read the following blog for more information:

That is enough for today!

Q2 “Government spending which is accompanied by a bond sale to the private sector adds less to aggregate demand than would be the case if there was no bond sale.”

What is the answer if the question says:

“Government spending which is accompanied by a bond sale to the private sector adds less to aggregate demand SOMETIME IN THE FUTURE than would be the case if there was no bond sale”?

Dear Fed Up (2010/07/11 at 7:40)

What exactly is your hypothesis and why?

best wishes

bill

Bill et al.

When the UK government refers to “government finances” would it be fair for me to refer to this as an oxymoron?

(p.s. i’ve changed my email to an account I actually use.)

Kind Regards

Charlie

Dear CharlesJ

The term “government finances” are definitely an oxymoron.

best wishes

bill

My “hypothesis” (maybe not the correct term) is that ALL debt (whether owed by the rich, the gov’t, or on the lower and middle class) that is spent “brings something forward from the future”. Combine this with a price inflation target, and an economy can get time differences between spending and earning among the different groups that can cause budget/balance sheet problems for certain groups that have poor assumptions about their real earnings in the future.

It seems to me the fed, a lot of economists, a lot of bankers, and the rich have certain assumptions too.

(a) an economy has unlimited demand so it is ALWAYS supply constrained

(b) if people live longer, they should ALWAYS work longer

Now if out in the real world these 2 assumptions are FALSE but the fed is making policy based on them being true, how would that play out in the real world economy?

I’m trying to get people to focus on:

1) retirement date changes

2) wealth/income inequality

3) the time differences between earning and spending debt can create

4) the fungible money supply (the amount of currency vs. the amount of debt)

5) whether an economy is supply constrained vs. demand constrained

Do you remember the wealth/income inequality spreadsheet I sent about the “card” economy?

The spoiled, rich kid ends up with all the assets, eventually “captures” the gov’t (parent), and the other kid ends up with no assets. If someone tries to help the kid with no assets, the spoiled, rich one retaliates.

bill said: “why?”

I’m trying to get people to understand that an aggregate supply shock (from positive productivity growth and/or cheap labor), should be “handled” with an increase in currency (present demand in the present) NOT with an increase in debt (future demand brought to the present and usually because interest rates fall).

Back to retirement date changes and in a wealth/income inequality world that has a low, positive price inflation target; are the rich accumulating everyone else’s retirement while the lower and middle class are losing theirs?

‘However, the reality is that:

* Building bank reserves does not increase the ability of the banks to lend.”

This is true in the current system. However, isn’t this solely due to our current system?

Suppose that there was no central bank discount window — and no banks were trusted sufficiently to be able to issue currentcy. Then they would be reserves-constrained, correct?

Suppose alternatively that every bank was about to hit the FDIC limit for minimum reserves and be liquidated if it didn’t have enough. Then wouldn’t they, in some sense, be reserves-constrained?