Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

Saturday Quiz – July 17, 2010 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for yesterday’s quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of modern monetary theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

The National Accounting identity says that total spending is the sum of household consumption, private investment, government spending and net exports. To understand this in terms of a stock-flow consistent macroeconomics, where we have to always trace the impact of flows during a period on the relevant stocks at the end of the period, we would interpret the spending components as flows add to the stock of aggregate demand which in turn impacts on the final production (Gross Domestic Product).

The answer is false.

This is a very easy test of the difference between flows and stocks. All expenditure aggregates – such as government spending and investment spending are flows. They add up to total expenditure or aggregate demand which is also a flow rather than a stock. Aggregate demand (a flow) in any period and determines the flow of income and output in the same period (that is, GDP).

So while flows can add to stock – for example, the flow of saving adds to wealth or the flow of investment adds to the stock of capital – flows can also be added together to form a larger flow (for example, aggregate demand).

Question 2:

Assume the current public debt to GDP ratio is 100 per cent and that the nominal interest rate and the inflation rate remain constant and zero. Under these circumstances it is impossible to reduce a public debt to GDP ratio, using an austerity package if the rise in the primary surplus to GDP ratio is always exactly offset by negative GDP growth rate of the same percentage value.

The answer is True.

This question plays on the first but investigates a difference aspect of the framework outlined above.

While Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) places no particular importance in the public debt to GDP ratio for a sovereign government, given that insolvency is not an issue, the mainstream debate is dominated by the concept.

The unnecessary practice of fiat currency-issuing governments of issuing public debt $-for-$ to match public net spending (deficits) ensures that the debt levels will rise when there are deficits.

Rising deficits usually mean declining economic activity (especially if there is no evidence of accelerating inflation) which suggests that the debt/GDP ratio may be rising because the denominator is also likely to be falling or rising below trend.

Further, historical experience tells us that when economic growth resumes after a major recession, during which the public debt ratio can rise sharply, the latter always declines again.

It is this endogenous nature of the ratio that suggests it is far more important to focus on the underlying economic problems which the public debt ratio just mirrors.

Mainstream economics starts with the flawed analogy between the household and the sovereign government such that any excess in government spending over taxation receipts has to be “financed” in two ways: (a) by borrowing from the public; and/or (b) by “printing money”.

Neither characterisation is remotely representative of what happens in the real world in terms of the operations that define transactions between the government and non-government sector.

Further, the basic analogy is flawed at its most elemental level. The household must work out the financing before it can spend. The household cannot spend first. The government can spend first and ultimately does not have to worry about financing such expenditure.

However, in mainstream (dream) land, the framework for analysing these so-called “financing” choices is called the government budget constraint (GBC). The GBC says that the budget deficit in year t is equal to the change in government debt over year t plus the change in high powered money over year t. So in mathematical terms it is written as:

which you can read in English as saying that Budget deficit = Government spending + Government interest payments – Tax receipts must equal (be “financed” by) a change in Bonds (B) and/or a change in high powered money (H). The triangle sign (delta) is just shorthand for the change in a variable.

However, this is merely an accounting statement. In a stock-flow consistent macroeconomics, this statement will always hold. That is, it has to be true if all the transactions between the government and non-government sector have been corrected added and subtracted.

So in terms of MMT, the previous equation is just an ex post accounting identity that has to be true by definition and has not real economic importance.

But for the mainstream economist, the equation represents an ex ante (before the fact) financial constraint that the government is bound by. The difference between these two conceptions is very significant and the second (mainstream) interpretation cannot be correct if governments issue fiat currency (unless they place voluntary constraints on themselves to act as if it is).

Further, in mainstream economics, money creation is erroneously depicted as the government asking the central bank to buy treasury bonds which the central bank in return then prints money. The government then spends this money. This is called debt monetisation and you can find out why this is typically not a viable option for a central bank by reading the Deficits 101 suite – Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 3.

Anyway, the mainstream claims that if governments increase the money growth rate (they erroneously call this “printing money”) the extra spending will cause accelerating inflation because there will be “too much money chasing too few goods”! Of-course, we know that proposition to be generally preposterous because economies that are constrained by deficient demand (defined as demand below the full employment level) respond to nominal demand increases by expanding real output rather than prices. There is an extensive literature pointing to this result.

So when governments are expanding deficits to offset a collapse in private spending, there is plenty of spare capacity available to ensure output rather than inflation increases.

But not to be daunted by the “facts”, the mainstream claim that because inflation is inevitable if “printing money” occurs, it is unwise to use this option to “finance” net public spending.

Hence they say as a better (but still poor) solution, governments should use debt issuance to “finance” their deficits. Thy also claim this is a poor option because in the short-term it is alleged to increase interest rates and in the longer-term is results in higher future tax rates because the debt has to be “paid back”.

Neither proposition bears scrutiny – you can read these blogs – Will we really pay higher taxes? and Will we really pay higher interest rates? – for further discussion on these points.

The mainstream textbooks are full of elaborate models of debt pay-back, debt stabilisation etc which all claim (falsely) to “prove” that the legacy of past deficits is higher debt and to stabilise the debt, the government must eliminate the deficit which means it must then run a primary surplus equal to interest payments on the existing debt.

A primary budget balance is the difference between government spending (excluding interest rate servicing) and taxation revenue.

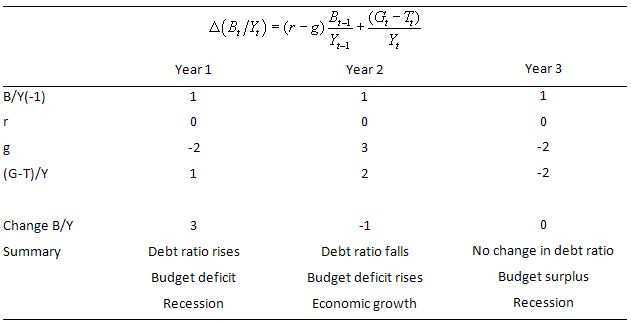

The standard mainstream framework, which even the so-called progressives (deficit-doves) use, focuses on the ratio of debt to GDP rather than the level of debt per se. The following equation captures the approach:

So the change in the debt ratio is the sum of two terms on the right-hand side: (a) the difference between the real interest rate (r) and the GDP growth rate (g) times the initial debt ratio; and (b) the ratio of the primary deficit (G-T) to GDP.

The real interest rate is the difference between the nominal interest rate and the inflation rate.

The standard formula above can easily demonstrate that a nation running a primary deficit can reduce its public debt ratio over time.

Furthermore, depending on contributions from the external sector, a nation running a deficit will more likely create the conditions for a reduction in the public debt ratio than a nation that introduces an austerity plan aimed at running primary surpluses.

Here is why that is the case.

The following Table presents three situations which help us work out the result. You can see that there is a recession being encountered with negative GDP growth of 2 per cent (this is also a decline in real GDP because the inflation rate is zero).

Now the government responds to the deficit terrorists and tries to reduce the public debt ratio by running a primary budget surplus of 2 per cent of GDP – it is a negative sign in the table because the construction is (G – T)/GDP which means a surplus is a negative number.

From the formula, the change in the public debt ratio is zero.

As long as the primary surplus as a per cent of GDP is exactly equal to the negative GDP growth rate, there can be no reduction in the public debt ratio.

Of-course, this strategy, which is being pushed onto governments by the conservatives now will likely have to consequences.

First, it will probably push the GDP growth rate further into negative territory which, other things equal, pushes the public debt ratio up.

Second, as GDP growth declines further, the automatic stabilisers will push the balance result towards (and into after a time) deficit, which, given the borrowing rules that governments volunatarily enforce on themselves, also pushed the public debt ratio up.

So austerity packages, quite apart from their highly destructive impacts on real standards of living and social standards, typically fail to reduce public debt ratios and usually increase them.

So even if you were a conservative and erroneously believed that high public debt ratios were the devil’s work, it would be foolish (counter-productive) to

impose fiscal austerity on a nation as a way of addressing your paranoia. Better to grit your teeth and advocate higher deficits and higher real GDP growth.

That strategy would also be the only one advocated by MMT.

Question 3:

If the household saving ratio rises and there is an external deficit then Modern Monetary Theory tells us that the government must increase net spending to fill the private spending gap or else national output and income will fall.

The answer is False.

This question tests one’s basic understanding of the sectoral balances that can be derived from the National Accounts. The secret to getting the correct answer is to realise that the household saving ratio is not the overall sectoral balance for the private domestic sector.

In other words, if you just compared the household saving ratio with the external deficit and the budget balance you would be leaving an essential component of the private domestic balance out – private capital formation (investment).

To understand that, in macroeconomics we have a way of looking at the national accounts (the expenditure and income data) which allows us to highlight the various sectors – the government sector and the non-government sector (and the important sub-sectors within the non-government sector).

So we start by focusing on the final expenditure components of consumption (C), investment (I), government spending (G), and net exports (exports minus imports) (NX).

The basic aggregate demand equation in terms of the sources of spending is:

GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

In terms of the uses that national income (GDP) can be put too, we say:

GDP = C + S + T

which says that GDP (income) ultimately comes back to households who consume, save (S) or pay taxes (T) with it once all the distributions are made.

So if we equate these two ideas sources of GDP and uses of GDP, we get:

C + S + T = C + I + G + (X – M)

Which we then can simplify by cancelling out the C from both sides and re-arranging (shifting things around but still satisfying the rules of algebra) into what we call the sectoral balances view of the national accounts.

There are three sectoral balances derived – the Budget Deficit (G – T), the Current Account balance (X – M) and the private domestic balance (S – I).

These balances are usually expressed as a per cent of GDP but we just keep them in $ values here:

(S – I) = (G – T) + (X – M)

The sectoral balances equation says that total private savings (S) minus private investment (I) has to equal the public deficit (spending, G minus taxes, T) plus net exports (exports (X) minus imports (M)), where net exports represent the net savings of non-residents.

You can then manipulate these balances to tell stories about what is going on in a country.

For example, when an external deficit (X – M < 0) and a public surplus (G – T < 0) coincide, there must be a private deficit. So if X = 10 and M = 20, X – M = -10 (a current account deficit). Also if G = 20 and T = 30, G – T = -10 (a budget surplus). So the right-hand side of the sectoral balances equation will equal (20 – 30) + (10 – 20) = -20.

As a matter of accounting then (S – I) = -20 which means that the domestic private sector is spending more than they are earning because I > S by 20 (whatever $ units we like). So the fiscal drag from the public sector is coinciding with an influx of net savings from the external sector. While private spending can persist for a time under these conditions using the net savings of the external sector, the private sector becomes increasingly indebted in the process. It is an unsustainable growth path.

So if a nation usually has a current account deficit (X – M < 0) then if the private domestic sector is to net save (S – I) > 0, then the public budget deficit has to be large enough to offset the current account deficit. Say, (X – M) = -20 (as above). Then a balanced budget (G – T = 0) will force the domestic private sector to spend more than they are earning (S – I) = -20. But a government deficit of 25 (for example, G = 55 and T = 30) will give a right-hand solution of (55 – 30) + (10 – 20) = 15. The domestic private sector can net save.

So by only focusing on the household saving ratio in the question, I was only referring to one component of the private domestic balance. Clearly in the case of the question, if private investment is strong enough to offset the household desire to increase saving (and withdraw from consumption) then no spending gap arises.

In the present situation in most countries, households have reduced the growth in consumption (as they have tried to repair overindebted balance sheets) at the same time that private investment has fallen dramatically.

As a consequence a major spending gap emerged that could only be filled in the short- to medium-term by government deficits if output growth was to remain intact. The reality is that the budget deficits were not large enough and so income adjustments (negative) occurred and this brought the sectoral balances in line at lower levels of economic activity.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Barnaby, better to walk before we run

- Stock-flow consistent macro models

- Norway and sectoral balances

- The OECD is at it again!

Question 4:

Even though the money multiplier found in macroeconomics textbooks is a flawed description of the way the monetary system operates, having some positive minimum reserve requirements does constrain credit creation activities of the private banks more than if you have no requirements other than the rule that balances have to be non-zero.

The answer is False.

While many nations do not have minimum reserve requirements other than reserve account balances at the central bank have to remain non-zero, other nations do persist in these gold standard artefacts. The ability of banks to expand credit is unchanged across either type of country.

These sorts of “restrictions” were put in place to manage the liabilities side of the bank balance sheet in the belief that this would limit volume of credit issued.

It became apparent that in a fiat monetary system, the central bank cannot directly influence the growth of the money supply with or without positive reserve requirements and still ensure the financial system is stable.

The reality is that every central bank stands ready to provide reserves on demand to the commercial banking sector. Accordingly, the central bank effectively cannot control the reserves that are demanded but it can set the price.

However, given that monetary policy (mostly ignoring the current quantitative easing type initiatives) is conducted via the central bank setting a target overnight interest rate the central bank is really required to provide the reserves on demand at that target rate. If it doesn’t then it loses the ability to ensure that target rate is sustained each day.

Imagine the central bank tried to lend reserves to banks above the target rate. Immediately, banks with surplus reserves could lend above the target rate and below the rate the central bank was trying to lend at. This would lead to competitive pressures which would drive the overnight rate upwards and the central bank loses control of its monetary policy stance.

Every central bank conducts its liquidity management activities which allow it to maintain control of the target rate and therefore monetary policy with the knowledge of what the likely reserve demands of the banks will be each day. They take these factors into account when they employ repo lending or open market operations on a daily basis to manage the cash system and ensure they reach their desired target rate.

The details vary across countries (given different institutional arrangements relating to timing etc) but the operations are universal to central banking.

While admitting that the central bank will always provide reserves to the banks on demand, some will still try argue that by the capacity of the central bank to set the price of the reserves they provide ensures it can stifle bank lending by hiking the price it provides the reserves at.

The reality of central bank operations around the world is that this doesn’t happen. Central banks always provide the reserves at the target rate.

So as I have described often, commercial banks lend to credit-worthy customers and create deposits in the process. This is an on-going process throughout each day. A separate area in the bank manages its reserve position and deals with the central bank.

The two sections of the bank do not interact in any formal way so the reserve management section never tells the loan department to stop lending because they don’t have reserves. The banks know they can get the reserves from the central bank in whatever volume they need to satisfy any conditions imposed by the central bank at the overnight rate (allowing for small variations from day to day around this).

If the central bank didn’t do this then it would risk failure of the financial system.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Oh no – Bernanke is loose and those greenbacks are everywhere

- Building bank reserves will not expand credit

- Building bank reserves is not inflationary

- Deficit spending 101 Part 1

- Deficit spending 101 Part 2

- Deficit spending 101 Part 3

Question 5:

It is clear that EMU nations cannot use the exchange rate mechanism to adjust for trading imbalances arising from a lack of competitiveness within the Eurozone. With fiscal and monetary policy tied by the EMU arrangements, the only adjustment mechanism left is to reduce wages and prices to restore competitiveness. While harsh this will ultimately improve the competitive position of Greece, Portugal, Ireland and other nations currently in external deficit.

The answer is False.

The temptation is to accept the rhetoric after understanding the constraints that the EMU places on member countries and conclude that the only way that competitiveness can be restored is to cut wages and prices. That is what the dominant theme emerging from the public debate is telling us.

However, deflating an economy under these circumstance is only part of the story and does not guarantee that a nations competitiveness will be increased.

We have to differentiate several concepts: (a) the nominal exchange rate; (b) domestic price levels; (c) unit labour costs; and (d) the real or effective exchange rate.

It is the last of these concepts that determines the “competitiveness” of a nation. This Bank of Japan explanation of the real effective exchange rate is informative. Their English-language services are becoming better by the year.

Nominal exchange rate (e)

The nominal exchange rate (e) is the number of units of one currency that can be purchased with one unit of another currency. There are two ways in which we can quote a bi-lateral exchange rate. Consider the relationship between the $A and the $US.

- The amount of Australian currency that is necessary to purchase one unit of the US currency ($US1) can be expressed. In this case, the $US is the (one unit) reference currency and the other currency is expressed in terms of how much of it is required to buy one unit of the reference currency. So $A1.60 = $US1 means that it takes $1.60 Australian to buy one $US.

- Alternatively, e can be defined as the amount of US dollars that one unit of Australian currency will buy ($A1). In this case, the $A is the reference currency. So, in the example above, this is written as $US0.625= $A1. Thus if it takes $1.60 Australian to buy one $US, then 62.5 cents US buys one $A. (i) is just the inverse of (ii), and vice-versa.

So to understand exchange rate quotations you must know which is the reference currency. In the remaining I use the first convention so e is the amount of $A which is required to buy one unit of the foreign currency.

International competitiveness

Are Australian goods and services becoming more or less competitive with respect to goods and services produced overseas? To answer the question we need to know about:

- movements in the exchange rate, ee; and

- relative inflation rates (domestic and foreign).

Clearly within the EMU, the nominal exchange rate is fixed between nations so the changes in competitiveness all come down to the second source and here foreign means other nations within the EMU as well as nations beyond the EMU.

There are also non-price dimensions to competitiveness, including quality and reliability of supply, which are assumed to be constant.

We can define the ratio of domestic prices (P) to the rest of the world (Pw) as Pw/P.

For a nation running a flexible exchange rate, and domestic prices of goods, say in the USA and Australia remaining unchanged, a depreciation in Australia’s exchange means that our goods have become relatively cheaper than US goods. So our imports should fall and exports rise. An exchange rate appreciation has the opposite effect.

But this option is not available to an EMU nation so the only way goods in say Greece can become cheaper relative to goods in say, Germany is for the relative price ratio (Pw/P) to change:

- If Pw is rising faster than P, then Greek goods are becoming relatively cheaper within the EMU; and

- If Pw is rising slower than P, then Greek goods are becoming relatively more expensive within the EMU.

The inverse of the relative price ratio, namely (P/Pw) measures the ratio of export prices to import prices and is known as the terms of trade.

The real exchange rate

Movements in the nominal exchange rate and the relative price level (Pw/P) need to be combined to tell us about movements in relative competitiveness. The real exchange rate captures the overall impact of these variables and is used to measure our competitiveness in international trade.

The real exchange rate (R) is defined as:

R = (e.Pw/P) (2)

where P is the domestic price level specified in $A, and Pw is the foreign price level specified in foreign currency units, say $US.

The real exchange rate is the ratio of prices of goods abroad measured in $A (ePw) to the $A prices of goods at home (P). So the real exchange rate, R adjusts the nominal exchange rate, e for the relative price levels.

For example, assume P = $A10 and Pw = $US8, and e = 1.60. In this case R = (8×1.6)/10 = 1.28. The $US8 translates into $A12.80 and the US produced goods are more expensive than those in Australia by a ratio of 1.28, ie 28%.

A rise in the real exchange rate can occur if:

- the nominal e depreciates; and/or

- Pw rises more than P, other things equal.

A rise in the real exchange rate should increase our exports and reduce our imports.

A fall in the real exchange rate can occur if:

- the nominal e appreciates; and/or

- Pw rises less than P, other things equal.

A fall in the real exchange rate should reduce our exports and increase our imports.

In the case of the EMU nation we have to consider what factors will drive Pw/P up and increase the competitive of a particular nation.

If prices are set on unit labour costs, then the way to decrease the price level relative to the rest of the world is to reduce unit labour costs faster than everywhere else.

Unit labour costs are defined as cost per unit of output and are thus ratios of wage (and other costs) to output. If labour costs are dominant (we can ignore other costs for the moment) so total labour costs are the wage rate times total employment = w.L. Real output is Y.

So unit labour costs (ULC) = w.L/Y.

L/Y is the inverse of labour productivity(LP) so ULCs can be expressed as the w/(Y/L) = w/LP.

So if the rate of growth in wages is faster than labour productivity growth then ULCs rise and vice-versa. So one way of cutting ULCs is to cut wage levels which is what the austerity programs in the EMU nations (Ireland, Greece, Portugal etc) are attempting to do.

But LP is not constant. If morale falls, sabotage rises, absenteeism rises and overall investment falls in reaction to the extended period of recession and wage cuts then productivity is likely to fall as well. Thus there is no guarantee that ULCs will fall by any significant amount.

Bill,

you must be laughing now.

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/07/17/more-on-deficit-limits/

Even big guns make silly statements or even worse simply don’t get MMT. Even I after few months of reading your blog can tell, that Krugman does not quite understand MMT, fiat money, the role of taxation etc. I am a bit harsh and I really like the man, but regardless.

good follow up on http://www.creditwritedowns.com/2010/07/misunderstanding-modern-monetary-theory.html

Bill, thanks for this. I wonder if you had any comments on the Krugman – Gailbraith exchange today which seems to be right up your alley. Links below:

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/07/17/i-would-do-anything-for-stimulus-but-i-wont-do-that-wonkish/

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/07/17/more-on-deficit-limits/

Hrvoje got there first!

Dear Bill,

Re Krugman and MMT: the more Brer Bear encouraged Brer Rabbit to beat up the tar baby (MMT), the more Brer Rabbit got stuck – and Brer Bear had a good old laugh!

Cheers ….

jrbarch

I hope I get time to comment on the Krugman – Gailbraith exchange.

They are getting a lot closer to actually saying price inflating with currency vs. price inflating with debt.

I think they even mention some time differences (rather unknowingly?).

Glad to see everyone discussing the Krug/Galbraith exchange. I found it over at Mark Thomas site. Here was an interesting comment by Nick Rowe on Thomas site;

“Paul Krugman’s comment that there is a problem because at some point

“…money that the government prints won’t just sit there, it will feed inflation, and the government will indeed need to persuade the private sector to make resources available for government use.”

shows that he doesn’t understand modern monetary theory.

Abba Lerner in Functional Finance (1943) first made the argument that the level of public indebtedness doesn’t matter and that the best way to deal with involuntary unemployment is for Big Government to spend and replace private sector saving. Destabilizing inflation only occurs when government and private sector compete amongst themselves for scarce resources. (Lerner spent the second half of his life focused on cost-push inflation — he called it “seller’s inflation” — but it is a side problem.)

The point Krugman misses is that inflation is what the economy needs! It is part of the solution, not the problem. MMT proponents fully recognize that inflation is a limiting factor, but they maintain that low inflation is compatible with near zero unemployment. Unemployment is their primary worry.

Dr. Krugman needs to bone up on MMT. He should read Warren Mosler, Bill Mitchell, Randall Wray or more from Jamie Gailbraith to sort out his basic misunderstanding.

More importantly, there IS a problem with MMT. It is that MMT is indifferent between the private sector and the government sector. A country can find itself in a debt trap in which the private sector is permanently unable to maintain full employment. When the government “fills in the gap” by spending, the private sector disspends more. The result is a creeping market-socialism as the private sector whithers aways.

This is not theory. It describes Japan for the past 20 years. Japan is a so-called “unconstrained” country with a fiat and floating currency, hence the MoF can issue all the debt it wants. MMT believes this is a good thing. But the effect of nearly twenty years of excessive spending is that much of its private sector (including the banking system) has become zombified and the economy has become severely distorted.

MMT is indifferent to the fact that the Nikkei has fallen over 75% over the past 20 years. They point to the fact that bond vigilantes have not struck and that 10 year JGB bond yields are 1.2%. But the inability of a bond market to discipline a fiat government plagued with a perpetual output gap is a BAD THING. Japan’s fundamental problem is that its excess capacity cannot clear. MMT enables and cheers on this huge distotion.

I am no apologist for unbridled neo-Austrian capitalism. But every day the developed world is being forced to choose between market-socialism and capitalism. The Lerner/Lange market socialists are winning these days, and not just in Japan!

This — and not inflation — is what Dr. Krugman should be focused on. But it means arguing from the right, and it is hard for him to do. Keynes himself was sympathetic to Lerner, but he never was unwilling to accept the extreme left-wing implications of his theory.

Separately, thank you Mark for posting yesterday the piece I sent you by Kalecki “Political Aspects of Full Employment”.

Your readers might like to see Lerner’s piece on Functional Finance. Here is a link to this brilliant paper.

http://k.web.umkc.edu/keltons/Papers/501/functional%20finance.pdf

Nick R.

Kyoto – Japan”

He’s making some pretty bold claims about what MMT is indifferent to. Claims that it “cheers” on Japans excess capacity that cannot clear.

Good to see people talking about it. I’d love to see Warren, Bill , Marshall, Scott, Lynn Parramore and Randall Wray scoot on over to Thoma’s site and comment in this thread en masse. Let the readers get “MMTs view” from someone other than Nick Rowe.

Greg,

Are you sure that is Nick Rowe?

Yeah, I don’t think that’s Nick Rowe. One, Nick Rowe lives in Canada, not Japan. Two, whenever Nick Rowe comments on Professor Thoma’s website a link back to his website is included with his name. And three, other comments in the thread by that commentator seem to be pretty supportive of the MMT position, but Nick Rowe is not really a supporter of MMT at all.

That is 100 % not Nick Rowe.

How can it be Nick Rowe ?

Good idea to tell Nick Rowe about this confusion.

Better not.

Could cause unintended consequences.

Like a post from Nick Rowe on the topic.

🙂

Rofl. Ha Ha Ha.

Welllllllllllllllll……. come to think of it I’m NOT sure its Nick Rowe. I jumped to a conclusion because I have seen him post on Marks site before and he has had some MMT discussions on HIS site. I would not be surprised for him to make the comments about MMT that were made but…………………..

I saw the Japan knew he was Canadien but figured he might be in Japan doing a post…………………. see how nasty rumors get started!!

Sorry, to sound like a broken record, but I think Nick R. sorely misinterprets MMT in some areas, while also getting other points correct, for sure.

“MMT is indifferent b/n public and private sector.” Really? Who said that? Arguing for procyclical fiscal action seems to me to be quite a bit different from arguing for indifference b/n the two sectors.

“The result is a creeping market-socialism as the private sector whithers aways.” And what about where the govt cuts taxes instead of spending. Or did Nick R. miss this MMT policy recommendation that is plastered virtually everywhere on our blogs?

“But the effect of nearly twenty years of excessive spending is that much of its private sector (including the banking system) has become zombified and the economy has become severely distorted.”

Of course, the source of these problems was the popping of two asset price bubbles (stocks and real estate). And MMT spends A LOT of time talking about how to deal with those–and I’m not talking about deficits here. Ever heard of Minsky? Further, like the US now, Japan simply allowed the zombie, vampire squid financial system to limp along–MMT’ers have made number (again, non-deficit related) proposals for this. Did Nick R. somehow miss that?

“MMT is indifferent to the fact that the Nikkei has fallen over 75% over the past 20 years. They point to the fact that bond vigilantes have not struck and that 10 year JGB bond yields are 1.2%. But the inability of a bond market to discipline a fiat government plagued with a perpetual output gap is a BAD THING. Japan’s fundamental problem is that its excess capacity cannot clear. MMT enables and cheers on this huge distotion.”

AGain, a complete misreading of the intentions of MMT. MMT’ers point here is that the deficits did not create inflation and did not result in rising interest rates. I have never seen an MMT’er make the case that the Japanese policy response was actually well-crafted, and I have never heard an MMT’er say that the things Nick R. mentions are “good.” And MMT’ers have quite a bit of criticism of how Japan actually carried out policy the past 2 decades (both financial reform, or lack thereof, and stop/start fiscal policy).

“This is not theory. It describes Japan for the past 20 years. Japan is a so-called “unconstrained” country with a fiat and floating currency, hence the MoF can issue all the debt it wants. MMT believes this is a good thing. But the effect of nearly twenty years of excessive spending is that much of its private sector (including the banking system) has become zombified and the economy has become severely distorted”

I can’t think of one MMT’er that would actually agree with this characterization of Japan’s policy (20 years of excessive spending? how about 20 years of stop/start fiscal policy–that’s how Marshall Auerback characterizes it, and he lived there, too, Nick R.). Again, Nick also misses the vast MMT literature on financial reform, conveniently.

So, sorry Nick R. If you want to have a debate with MMT, then get your MMT fact right. You’ve got some of them, but then you’ve assumed that’s the end of the story. You’re free to disagree with MMT all you want, but here you’re just like dozens of others peddling a dizzying misunderstanding of MMT to others.

Bill,

I feel your answer to question 3 is a bit tight. If the savings ratio rises, this will reduce consumption demand. Unless government steps in to offset this, we get a fall in output and employment. Now sure, if the fall in consumption is offset by a rise in investment, then no govt action is necessary. But in that case there is no private spending gap, as the question presumes (I quote)

“government must increase net spending to fill the private spending gap or else national output and income will fall.”

For a blend of amusement and horror, a vigorous discussion of interest on reserves in the comment section of a Thoma post, where the commenters look like they all flew in from Sumner’s blog:

http://moneywatch.bnet.com/economic-news/blog/maximum-utility/dont-expect-miracles-from-monetary-policy/699/#comments

From the comments in anon’s bnet link:

SMIA1948:

“If you look at the Treasury yield curve right now, you will see

that the Fed is paying an above-market interest rate on bank

reserves, which amount to 1-day T-bills. As long as they do

this, it won’t matter how much they expand their balance

sheet–the banks will simply sit on the reserves that the Fed

creates. Paying interest on bank reserves is one of those

inexplicable bad ideas. The Fed should stop doing this

immediately.”

Well, I’m glad to see someone else thinks that (central) bank reserves are actually overnight gov’t debt in disguise (1-day T-bills).

Anyone ever wonder why the gov’t does not issue gov’t debt with less than a 1-month maturity (I think)?

How about does anyone think (central) bank reserves are “faux” currency?

If the fed paid negative interest on excess (central) bank reserves, would the banks just redeem them for currency 1 to 1?

From Q1:

“So while flows can add to stock – for example, the flow of saving adds to wealth or the flow of investment adds to the stock of capital – flows can also be added together to form a larger flow (for example, aggregate demand).”

What are the different stocks?

Is the “fungible” money supply (amount of currency vs. amount of debt) the most important one?

From Q2:

“Further, the basic analogy is flawed at its most elemental level. The household must work out the financing before it can spend. The household cannot spend first. The government can spend first and ultimately does not have to worry about financing such expenditure.”

Let me see if I have this correct. A person goes to the bank or to a buddy to get a loan. At the bank, a NEW demand deposit is created for the person at the same time as the bond part WITH the idea that both interest and principle will be paid back over a certain period (the term of the loan). With a buddy, a current demand deposit or current currency (savings) is given to the person at the same time as the bond part WITH the idea that both interest and principle will be paid back over a certain period (the term of the loan). Therefore, there is no rollover risk. The currency printing entity will NOT bailout/monetize either loan. Debt default could happen in either case.

Now the gov’t is different since it “sort of” owns the currency printing entity (assuming it can issue its own currency). The gov’t adds a NEW demand deposit (gov’t check/mark up an account somewhere). This NEW demand deposit is usually NOT matched with the bond part at the same time AND the principle is NOT paid back over a certain period (the term of the loan). Therefore, there is rollover risk. However, the currency printing entity will probably monetize it if necessary. Debt default probably won’t happen.

Is that correct?

I will probably come back to the different times and the amount of currency printed in those times, especially in relationship to trying to expand supply more than demand.

“and/or a change in high powered money (H).”

What is your definition of high powered money? Is it currency?

“Hence they say as a better (but still poor) solution, governments should use debt issuance to “finance” their deficits. Thy also claim this is a poor option because in the short-term it is alleged to increase interest rates and in the longer-term is results in higher future tax rates because the debt has to be “paid back”.”

What if the debt has to be paid back because someone refuses to rollover the debt?

For example, what if china escapes its “dollar trap” by building up the economies in Africa, Latin America, and other parts of Asia?

They say we are not rolling over the debt. We want the currency. USA says we can’t tax that much to pay you back. They say fine, and we are cashing in the bonds for currency. The fed obliges and the dollar tanks. china loses an export market but has built up other ones and maybe its own domestic market. The USA is in trouble.

Q4, the way JKH and others have explained it is that positive minimum reserve requirements act as a tax that raises costs. This can affect profitability, which can affect whether a loan is made. Is it wording, or did I not understand them correctly?

Not as much time stuff as I first thought but and from:

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/07/17/more-on-deficit-limits/

“My response: there’s no question that right now there is no problem: if the Fed issues money (MY ADD: I assume to a bank), it will in fact just sit there. That’s what happens when you’re in a liquidity trap.

If by money he means currency, then try giving it to someone unemployed or making $20,000 a year or less. Let’s see what happens then.

“And there’s also no question that right now, the proposition that the government can “create wealth by printing money”, which some other commenters call absurd, is the simple truth: deficit-financed government spending, paid for with either debt or newly created cash, will put resources that would otherwise be idle to work.”

There is a prime example of why the term money should be gotten rid of by economists. He seems to mean either currency or debt. They are different.

Make it “… will put resources that would otherwise be idle to work IN THE PRESENT but could be idled again if it is debt (future demand brought to the present which could cause a drop in demand IN THE FUTURE).”

“But we won’t always be in this situation – or at least I hope not! Someday the private sector will see enough opportunities to want to invest its savings in plant and equipment, not leave them sitting idle, and the economy will return to more or less full employment without needing deficit spending to keep it there. At that point, money that the government prints won’t just sit there, it will feed inflation, and the government will indeed need to persuade the private sector to make resources available for government use.”

Why would time work the problems out if the spoiled and rich along with the fed are pursuing the same policies that got us to this point?

Negative real earnings growth on the lower and middle class (especially workers) and more debt on them to maintain a price inflation target, to trick them into working longer whether in the present and/or in the future, and to jack up stock prices to expand supply does NOT work when there are not more hours to work because of productivity growth and the economy has gone from supply constrained to demand constrained.

I don’t understand the answer to question 1. As I read it, the true/false part of the question states “…we would interpret the spending components as flows add to the stock of aggregate demand…” and the answer says “All expenditure aggregates – such as government spending and investment spending are flows.” So shouldn’t the answer be “true”?