I have received several E-mails over the last few weeks that suggest that the economics…

The myth of rational expectations

The increasingly alarmist commentator Niall Ferguson was at it again the Financial Times (July 20, 2010) in his article – Have Keynesians learnt nothing?. The article has a simple presumption – we are getting scared of deficits and as a result inflation is inevitable. What? We are scared because we expect there will be inflation and so we will act accordingly and start pushing up wages and prices to defend ourselves in real terms. The result will be inflation. This is a playback of the so-called rational expectations literature which Ferguson proudly cites as his authority. The problem is that the theory is defunct – it never was valid and only a butt of depressed cultists still hang on to it as their religion because they learned it when they were young and in doing so lost their capacity to experience the joys of wider education. We really must feel sorry for them.

Ferguson says:

It was said of the Bourbons that they forgot nothing and learned nothing. The same could easily be said of some of today’s latter-day Keynesians. They cannot and never will forget the policy errors made in the US in the 1930s. But they appear to have learned nothing from all that has happened in economic theory since the publication of their bible, John Maynard Keynes’s The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, in 1936.

This is an article that invokes all the failed mainstream macroeconomic economic theories (such as Rational Expectations, Ricardian Equivalent) as authorities and which claims solace by quoting the likes of Thomas Sargent, Robert Barro, Reinhart and Rogoff.

Sargent and Barro, in particular, still peddle arcane notions of economies that have very little resemblance to the world we live in. And over the last 30 years they have made spectacular predictions about the likely impact of government policy changes which have failed to materialise. Nothing they say should be taken seriously.

Ferguson then mounts his main argument:

… what we are witnessing today has less to do with the 1930s than with the 1940s: it is world war finance without the war.

But the differences are immense. First, the US financed its huge wartime deficits from domestic savings, via the sale of war bonds. Second, wartime economies were essentially closed, so there was no leakage of fiscal stimulus. Third, war economies worked at maximum capacity; all kinds of controls had to be imposed on the private sector to prevent inflation.

Today’s war-like deficits are being run at a time when the US is heavily reliant on foreign lenders, not least its rising strategic rival China (which holds 11 per cent of US Treasuries in public hands); at a time when economies are open, so American stimulus can end up benefiting Chinese exporters; and at a time when there is much under-utilised capacity, so that deflation is a bigger threat than inflation.

We could have a quiz on how many errors you can find in this tract of prose. Answer: many fundamental errors. Ferguson doesn’t understand how monetary systems operate.

It is true that the Great Depression only really ended with the onset of the Second World War. That was because the level of fiscal intervention reached a sufficient level to drive aggregate demand growth strong enough to fully absorb the growth in real capacity. The commitment to war overcame all the conservative attacks on deficits etc.

When I am asked what my solution to mass unemployment is I respond – declare a war on it!

But the government spent in the same way then as now. Effectively the gold standard was abandoned during the Great Depression (most countries were off it by 1932) and so governments ran fiat currency systems as they do now. Spending is a simple case of crediting bank accounts. There is no reliance on domestic saving or otherwise in facilitating this process.

The government didn’t have to sell war bonds then just as it doesn’t have to sell treasury bonds now. Both actions serve purposes other than to provide “funds” to the government to permit it to spend. The governments in both eras were not revenue constrained even if they acted as though they were. Those constraints were entirely voluntary.

Further, he really shows his ignorance when we read that the “US is heavily reliant on foreign lenders”. For what exactly? Not for spending. It can spend any time it wants and can alter legislation if that constrains them to spend in a particular order (that is, after selling bonds) should that ever be a problem.

But the US government spends in US dollars and the Japanese and Chinese do not issue that currency. The reality is that the Chinese and Japanese are reliant on the US consumer to satisfy their desire to accumulate financial assets denominated in the US dollar. The US is never dependent on the foreigners to conduct its fiscal initiatives.

The issue of fiscal leakage to the external economy often comes up in the conservative attacks on expansionary policy. It is a total mis-nomer. It just means the spending multiplier is smaller (given the import leakage) and so a greater expansionary impulse is required for a given identified aggregate demand gap.

What the conservatives are really saying is that the absolute size of the deficit increase will be larger in an open economy relative to a closed economy and that scares them. Poor things. I would recommend some Acceptance & Commitment Therapy for them to soothe their minds.

The fact is that the absolute size of a deficit has no meaning at all on its own.

Third, the war-time economies did require supply rationing to address supply shortages and to prevent inflationary outbreaks. At present, at least Ferguson acknowledges that the advanced countries have several years of excess capacity to absorb before inflationary dangers will be very pressing.

But still Ferguson claims that eventually the inflation will come:

When economies were growing sluggishly, that could be slow in coming. But there invariably came a point when money creation by the central bank triggered an upsurge in inflationary expectations.

So a wing and a prayer.

There are countless historical examples where growth periods driven by fiscal and monetary stimulus do not cause inflation.

The appeal to inflationary expectations is interesting. Ferguson introduces what is now a defunct approach to macroeconomics. Even the conservatives have all but abandoned it although the less players and the media still somehow hang onto it as a cult. I am referring to the notion of Rational Expectations.

Ferguson introduces his authority to justify his scaremongering:

In 1981 the US economist Thomas Sargent wrote a seminal paper on “The Ends of Four Big Inflations”. It was in many ways the epitaph for the Keynesian era. Western governments (not least the British) had discovered the hard way that deficits could not save them.

With double-digit inflation and rising unemployment, drastic remedies were called for. Looking back to central Europe in the 1920s – another era of war-induced debt explosions – Sargent demonstrated that only a quite decisive policy “regime-change” would bring stabilisation, because only that would suffice to alter inflationary expectations.

This is a dishonest bit of writing.

But first some background.

The Rational Expectations (RATEX) literature which evolved in the late 1970s claimed that government policy attempts to stimulate aggregate demand would be ineffective in real terms but highly inflationary.

People (you and me) anticipate everything the central bank or the fiscal authority is going to do and render it neutral in real terms (that is, policy changes do not have any real effects). But expansionary attempts will lead to accelerating inflation because agents predict this as an outcome of the policy and build it into their own contracts.

In other words, they cannot increase real output with monetary stimulus but always cause inflation. Please read my blog – Central bank independence – another faux agenda – for more discussion on this point.

The idea is that everyone understands the Quantity Theory of Money (QTM) which in symbols is written as MV = PQ. This means that the money stock (M) times the turnover per period (V) is equal to the price level (P) times real output (Q). The mainstream assume that V is fixed (despite empirically it moving all over the place) and claim that Q is always at full employment as a result of free market adjustments.

So this theory denies the existence of unemployment. The more reasonable mainstream economists (who probably have kids who cannot get a job at present) admit that short-run deviations in the predictions of the Quantity Theory of Money can occur but in the long-run all the frictions causing unemployment will disappear and the theory will apply.

In general, the Monetarists (the most recent group to revive the Quantity Theory of Money) claim that with V and Q fixed, then changes in M cause changes in P – which is the basic Monetarist claim that expanding the money supply is inflationary. They say that excess monetary growth creates a situation where too much money is chasing too few goods and the only adjustment that is possible is nominal (that is, inflation).

One of the contributions of Keynes was to show the Quantity Theory of Money could not be correct. He observed price level changes independent of monetary supply movements (and vice versa) which changed his own perception of the way the monetary system operated.

Further, with high rates of capacity and labour underutilisation at various times (including now) one can hardly seriously maintain the view that Q is fixed. There is always scope for real adjustments (that is, increasing output) to match nominal growth in aggregate demand. So if increased credit became available and borrowers used the deposits that were created by the loans to purchase goods and services, it is likely that firms with excess capacity will respond by increasing real output to maintain market share.

Then the conservatives add expectations to this theory. So once there is an inflation people form the view (expect) it to continue and act accordingly.

How do they form their expectations? This has been a long debate but the Rational Expectations (RATEX) theory argued that it was only reasonable to assume that people act rationally and use all the information available to them.

What information do they possess? Well RATEX theory claims that individuals (you and me) essentially know the true economic model that is driving economic outcomes and make accurate predictions of these outcomes with white noise (random) errors only. The expected value of the errors is zero so on average the prediction is accurate.

Everyone is assumed to act in this way and have this capacity. So we all understand the QTM and understand that whenever the central bank expands the monetary base or the treasury increases the deficit there will be inflation.

So “pre-announced” policy expansions or contractions will have no effect on the real economy. For example, if the government announces it will be expanding the deficit and adding new high powered money, we will also assume immediately that it will be inflationary and will not alter our real demands or supply (so real outcomes remain fixed). Our response will be to simply increase the value of all nominal contracts and thus generate the inflation we predict via our expectations.

These geniuses thought this was a devastating critique against government intervention. They formed a cult around the leaders (Sargent, Lucas, Wallace etc) and were as smug as pie at the time (early 1980s). I was a graduate student then and all these conservative wannabee PhD klutzes would walk around with Sargent’s 1980 book on Macroeconomics and think they had found god. It was puke territory.

The book, by the way, has zero macroeconomics in it. Or any that is recognisable as such. But it was the bible for the cult although most of the cultists couldn’t understand the mathematics that Sargent was good at. They faked it. I used to laugh in postgrad workshops and my favourite tease (coming from a maths background) was to suck some smarty conservative wannabee into revealing their total ignorance about some maths derivation in Sargent and other books. You couldn’t blame me – you had to have some fun someway given how sterile the material we were forced to endure was!

Anyway, Ferguson refers to Thomas Sargent’s 1981 paper – The Ends of Four Big Inflations as a “seminal” piece of work with relevance to the current situation. You can read Sargent’s paper from the NBER Archives for free. I wouldn’t bother though – it is really an appallingly deceptive piece.

Sargent says that RATEX theory:

… denies that there is any inherent momentum in the present process of inflation. This view maintains that firms and workers have now come to expect high rates of inflation in the future and that they strike inflationary bargains in the light of these expectations. However, it is held that people expect high rates of inflation in the future precisely because the government’s current and prospective monetary and fiscal policies warrant those expectations. Further, the current rate of inflation and people’s expectations about future rates of inflation may well seem to respond slowly to isolated actions of restrictive monetary and fiscal policy that are viewed as temporary departures from what is perceived as a long-term government policy involve high average rates of government deficits and monetary expansion in the future. Thus inflation only seems to have a momentum of its own; it is actually the long-term government policy of persistently running large deficits and creating money at high rates which imparts the momentum of the inflation rate (emphasis in the original).

Sargent’s paper considers four hyperinflations in the 1920s in Austria, Hungary, Germany, and Poland. His examples relate to fiat currencies where monetary expansion “was done on such a scale that it led to a depreciation of the currencies of spectacular proportions”. So extreme events with particular circumstances that are not remotely existing in any advanced nation in 2010.

Sargent claims that the RATEX cure for inflation would require:

… a change in the policy regime: there must be an abrupt change in the continuing government policy, or strategy, for setting deficits now and in the future that is sufficiently binding as to be widely believed. Economists do no now possess reliable, empirically tried and true models that can enable them to predict precisely how rapidly and with what disruption in terms of lost output and employment such a regime change will work its effects. How costly such a move would be in terms of foregone output and how long it would be in taking effect would depend partly on how resolute and evident the government’s commitment was.

So you can see where the austerity proponents are getting their direction from. They are full of this expectational argument – that we are all predicting higher taxes to pay back the deficits and so are saving now whereas business firms are predicting higher interest rates allegedly because of the public debt and so are refusing to invest. So the deficits are alleged to have crowded out private spending.

Cure: reverse the deficits (the austerity option) and suddenly all this pent up private spending will spring up and save the economy from being a scorched earth. Likelihood: there is no empirical evidence that his has ever happened. There is a huge body of empirical evidence that it does not happen.

Moreover, the austerity proponents also misrepresent the RATEX body of work. By claiming as Trichet did the other day that “(i)t is an error to think that fiscal austerity is a threat to growth and job creation” they are denying Sargent’s own recognition that withdrawing fiscal support will be costly and enduring.

In using this work of Sargent, Ferguson is also leading his readers astray. For example, Sargent notes that:

The essential measures that ended hyperinflation in each of Germany, Austria, Hungary, and Poland were, first, the creation of an independent central bank that was legally committed to refuse the government’s demand for additional unsecured credit and, second, a simultaneous alteration in the fiscal policy regime. These measures were interrelated and coordinated. They had the effect of binding the government to place its debt with private parties and foreign governments which would value that debt according to whether it was backed by sufficiently large prospective taxes relative to public expenditures. In each case that we have studied, once it became widely understood that the government would not rely on the central bank for its finances, the inflation terminated and the exchanges stabilized.

While we can dispute his theoretical basis the important point is that the situation that Sargent describes here as providing inflation stability even with rapid growth in high powered money is more or less the situation that exists today.

Governments do not borrow from central banks and have the ultimate power to collect taxes. The point is not that I think those things matter but Sargent clearly does. So Ferguson is using Sargent as an authority to scare the bejesus out of his readers but fails to admit that the current situation is just the situation that Sargent thinks is stable.

Sargent’s case studies also provide the same conclusion.

One should also note that while Ferguson claimed that the Keynesians “appear to have learned nothing from all that has happened in economic theory since the publication of their bible”, one of the co-founders of RATEX, Robert Lucas said during a 1995 interview after he received a Nobel Prize that (Source: Steven Pearlstein, “Chicago Economist Wins Nobel Prize: Lucas has Focused on Theoretical Issues,” San Jose Mercury News, Wednesday, October 11, 1995, p. 4A):

The Keynesian orthodoxy hasn’t been replaced by anything yet

Maybe Ferguson hasn’t caught up with the fact that most of the leading proponents of RATEX theory have abandoned it because it was a total crock!

RATEX theory only remains a reality for the remaining hard core cultists who would be lost without it. It has been exposed to be flawed in many ways – both in terms of its theoretical conception and in terms of its empirical relevance.

In a 1995 Business Week article – Commentary: Great Theory…as far as it Goes – Michael Mandel was commenting on the Nobel Prize award to Robert Lucas (one of the influential developers of rational expectations theory). Mandel wrote that:

The rational-expectations revolution that Lucas pioneered still dominates economic policymaking. The unwillingness of either the Bush or the Clinton Administrations to take strong measures against the 1990-91 recession and its aftermath reflected the influence of Lucas and his colleagues. In 1994, Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan suggested that hiking short-term interest rates would hold down long-term rates as investors lowered their views of future inflation, an idea that owes much to Lucas’ notion of rational expectations.

Yet … the theory of rational expectations has not lived up to its original promise. Unfortunately, models built on rational expectations do not reflect the real world as well as the old Keynesian models that they were supposed to replace …

Lucas’ theory leads to some unappealing conclusions. For one, it implies that most unemployment is voluntary, even in recessions–a result that would surprise most jobseekers. Similarly, believers in rational expectations often end up arguing that business cycles are illusions …

However, the real tragedy of rational expectations is that it supports a philosophy of government inaction at a time of rapid economic change.

The first (difficult to understand) point is that there is no aggregate (macroeconomic) validity in the RATEX theory. This deserves another blog but relates to the insights provided by the Sonnenschein-Mantel-Debreu Theorem.

In simple terms, and extending the notion of the fallacy of composition where what happens at the individual level will not hold at the aggregate level, the Sonnenschein-Mantel-Debreu theorem tells us that even if all individuals are rational and make decisions according to RATEX the aggregate household will not exhibit the same rational behaviour. So there is no macroeconomic representation of the theory.

But then the behavioural economics literature has categorically shown that the RATEX conception of human decision making as rational and far-sighted is totally flawed.

It is clearly not sensible to believe that households and firms know very much about what drives economic outcomes. While my blog readership is probably more informed than most can any of you predict with white noise errors only what is going to happen in the next 12 months. Do you seriously believe that people use the myriad of financial and economic data to determine every spending decision they take.

Does anyone believe that households are always rational and perfectly informed about all current and future events? If you understand the RATEX theory then you will realise that to get the predicted results highly unrealistic assumptions like this had to be made. Once they were relaxed the results fail to hold. In other words, they don’t hold in any world we live in as humans.

Ferguson tries to link RATEX with contemporary events:

The evidence is very clear from surveys on both sides of the Atlantic. People are nervous of world war-sized deficits when there isn’t a war to justify them. According to a recent poll published in the Financial Times, 45 per cent of Americans “think it likely that their government will be unable to meet its financial commitments within 10 years”. Surveys of business and consumer confidence paint a similar picture of mounting anxiety.

The remedy for such fears must be the kind of policy regime-change Sargent identified 30 years ago, and which the Thatcher and Reagan governments successfully implemented. Then, as today, the choice was not between stimulus and austerity. It was between policies that boost private-sector confidence and those that kill it.

First, these surveys mean nothing. Where does Ferguson show that these polling responses will fundamentally alter behaviour? And in what direction? And if we really believed there would be default we would be hoarding real things and gold not buying government debt instruments in increasing volumes (and not being able to get enough of it).

Second, it is interesting that Ferguson cites the Reagan years to justify his citing of Sargent’s work. My understanding of that period in US history is that in July of 1981 the US entered recession driven by tight monetary policy and the recession officially ended in November 1982.

The recovery was clearly the result of increased fiscal deficits and lower interest rates. All the RATEX-Chicago types went ballistic when the government started expanding and claimed the policy would fail because all the private agents would anticipate it rationally and build in higher inflation to their decision making and withdraw their spending. They predicted a renewed burst of high inflation.

In spite of their predictions, private investment and consumption spending rose. RATEX theory and Barro’s Ricardian Equivalence (all interrelated and all claiming that policy is ineffective) were demonstrated to have no application in the real world.

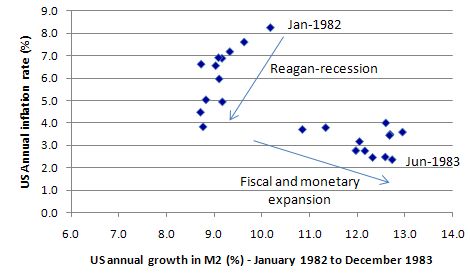

The reality is that inflation fell through 1983 as the economy recovered. Inflation fell from 10.3 per cent in 1981 to 3.2 per cent in 1983. The following graphs shows you the story. It shows the federal deficit (horizontal axis) and the annual US inflation rate (vertical axis) from January 1982 to December 1983.

The resulting boom lasted for an additional 7 years! The 1990-92 recession in the US was another classic case where the RATEX/Ricardian mob failed to predict anything that happened.

Further, just out of interest I compiled some other graphs relating deficits, monetary aggregates and inflation in the US. Here is what I came up with. I always caution people in using scatter diagrams to “prove” anything. You cannot prove anything with them but a good theory would show up as being supportable by such a diagram as an introductory empirical enquiry (that is, before more sophisticated statistical tools were used).

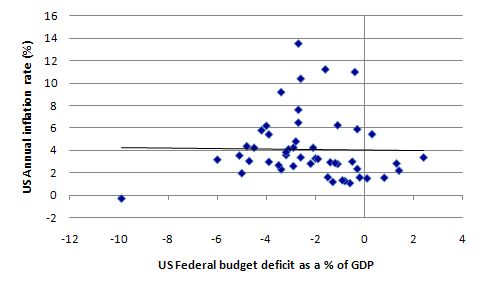

The following graph shows the annual federal US government deficit (-) as a per cent of GDP (horizontal axis) and the annual US inflation rate on the vertical axis from 1960 to 2009. The budget data comes from US Office of Management and Budget and the inflation data from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics. The black line is a simple linear regression.

Conclusion: No relationship at all. More formal causality tests I just ran also confirm that.

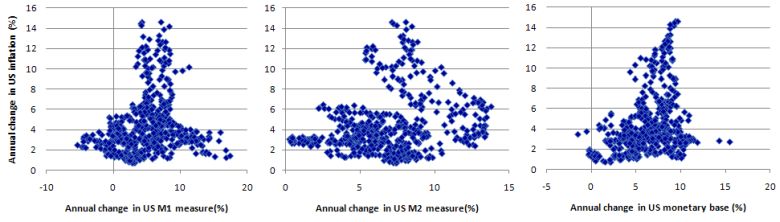

What about the relationship between annual US inflation and the various monetary aggregates? The following graphs show in order the annual change in M1, M2 and the monetary base (from Federal Reserve data) respectively left to right panels (horizontal axis) and the annual US inflation rate (vertical axis) from January 1960 to August 2008. I stopped there to exclude the rapid growth in the monetary aggregates in the current period which might distort the sample. The inclusion of those extreme observations which are associated with low inflation make the relationships even less distinct.

But overall, there is no quantity theory of money relationship shown in any of the charts.

The whole RATEX idea about recessions is bizarre. They assume that if aggregate demand falls and production starts to decline that workers and firms are temporarily fooled and keep their wage and prices too high. Once they realise that they lower prices and wages and the economy is alleged to recover as wealth effects (driven by the lower prices) restore demand and the lower wages increase demand for labour.

The conception is a dream. Milton Friedman was once asked how long a deflationary episode would have to be maintained (high interest rats) before inflation expectations were purged and he said perhaps 15 years. It seems that workers take a long time to adjust their “rational expectations”.

In the 1982 US recession, the unemployment rate took until 1987 to get back to the levels prior to the recession. So 7 years for the workers to decide they were being fooled!

It is clear that recessions do not occur in the way that the mainstream expectations school constructs them. They last too long and fiscal policy interventions are always successful.

As US institutional economist Michael Piore (1979: 10) noted:

Presumably, there is an irreducible residual level of unemployment composed of people who don’t want to work, who are moving between jobs, or who are unqualified. If there is in fact some such residual level of unemployment, it is not one we have encountered in the United States. Never in the post war period has the government been unsuccessful when it has made a sustained effort to reduce unemployment. (emphasis in original) [Unemployment and Inflation, Institutionalist and Structuralist Views, M.E. Sharpe, Inc., White Plains]

I was at a conference once as a young postgraduate student in the early 1980s at the height of the RATEX cult boom. Robert Lucas and Thomas Sargent were the new cult emperors and the brightest students who should be finding cures for cancer were blindly learning all this nonsense. At one point the famous James Tobin made a point along the lines that if everybody is rational and has the same information as the government and uses the same “model” of the economy that the policy makers use then what use is the economics profession.

If we can get our forecasts from the postman or around our kitchen tables what can we learn by studying economics (RATEX says nothing – so sack all the mainstream economists in universities). Why would we pay economic forecasting agencies (RATEX says they are useless because we already know what they are going to produce – so send all of them broke).

Further, Lucas himself abandoned the approach sometime later in his career as its logical and empirical shortcomings became obvious. Only the cultists hang on to it – like Ferguson.

The reality when there are recessions the mainstream belief in the efficacy of the market and the ineffectiveness of government is shown to be nonsensical.

Only theoretical structures that recognise the central role that aggregate demand plays in determining real GDP and employment and the central role of fiscal policy in managing aggregate demand can credibly explain recessions – their incidence, duration and solution.

Conclusion

It is pretty depressing recalling this literature. It was really a deplorable period of economic theorising. It got worse though when the RATEX cult leaders abandoned their cultists and started developing real business cycle theory. It was more of a joke than RATEX theory and died soon after again leaving a few devoted cult members chanting the mantra.

Fortunately most of the cult leaders of this time have more or less retired but there are thousands of cultists still out there with their dummies in their mouths looking for a new guru. I recommend therapy for all of them.

That is enough for today!

So … what about the close cousin of the REH — Efficient Markets Theory? If this is also wrong …. especially in its “weak” form …. does this mean that the “technical analysts” really can make money by reading the wiggles on the chart?

BTW — on the inflation vs monetary aggregates graphs …. the patterns in (a) reminds me of northern Germany/Denmark … (b) reminds me of the Malay Peninsula and the island of Sumatra (c) reminds me of the UK ….. there must be some significance to this…..

Ken

Bill,

would the myth of rational expectations extend to forcasters in Australia claiming that because our housing loans are recourse loans our property market is different to the rest of the world?

Recourse loans will magnify any drop in real estate prices as investment loans are called in triggering the sale of principle places of residence. Negative geared investment property owners have their family homes on the line.

Perhaps one of your readers could delve into the actual compounding effect any drop in real estate prices will have on prices because of recourse loans. Once this feedback loop gets started I cant see banks holding off what the USA calls forclosure.

Recourse loans will be the problem. Wake em up! Sure is a myth anyway and its more hope than rational. Not Macro sure but somthing for someone to pick up on. Cheers Punchy

off topic: Bill I hope you didn’t watch Joe Hockey on the 7:30 report, his ramblings on government spending, central bank operations and interest rates was too painful to watch – I had to turn it off.

damn you MDM! My wife switched over to masterchef just as he was trying to explain his ‘no policy’ policy on IR. I’m gonna have to look it up now….arrgh.

On Tech Analysis, don’t be totally dismissive of the ‘wiggles’……you really have to use it as a barometer of market sentiment and positioning, in concert with strict trading discipline. It does work if you know what you’re doing (including using different indicators as signals to ‘confirm’ your levels) and can be disiplined about cutting losses quickly as they occur. It’s not clairvoyance, but there is actually information content in there (stop losses, the weak side of the market etc etc).

And here’s a useful piece of research if you haven’t seen – Uncle Sam won’t go broke. Not strictly MMT, but a useful response to deficit hawks – http://www.levyforecast.com/recent-publications/docs/Uncle%20Sam%20Wont%20Go%20Broke.pdf

I bought Ferguson’s book “The Escent of Money”, the book is trying to convince people that Govt abilities to deficit spend always, from the perspective of history, is subjected to what he called Mr Bond Market’s discretion. So throughout history, Govt always trying to tame and gave assurance to Mr Bond Market that it’ll be able to meet its future payment, and if Mr Bond Market is not convince due to changes in govt policies, the bond market would punished that govt and this punishment not only would destroy the country’s economy but also would ensure that it lost the war, Ferguson uses Napoleon as one of the example, how a war was lost not because of French did not have an excellent army, but merely because the French had lost Mr Bond’s confidence.

But Ferguson didn’t make any distinction of Govt financing even after the gold standard has long been abandoned, he continues to use the same old argument as if we still using gold coin.

I though Ferguson’s book is came from his original idea, but after I read John Kenneth Galbraith’s book “MONEY, Whence it Came, Where it Went” published more than 3 decades earlier than ‘The Escent of Money” by Ferguson, I realized that much of the history from Ferguson’s book are taken from JK Galbraith’s book. Not only the historical narrative but also the analysis behinds those narratives have many resemblances to what has been written by the great JK Galbraith.

But one thing that set those 2 books apart.

Galbraith acknowledge that when gold was used as money, the ability of government to change the living standard of its people was very much subjected to the its ability to borrow from the bankers and bond market and crowing out does happen at this era. But JK Galbraith said that fiat money has gave government a new tool to effectively combat the unemployment problem, increase output capacity and increase social welfare.

Ferguson still cling to the history and asserted that the Mr Bond Market is keeping a close watch on Govt bond and Govt should ensure Mr Bond confidence by not spend too much.

Please read these two books and judge for yourself whom gave more sensible argument, the book written in 1975 by JK Galbraith or in 2008 by N Ferguson.

Excellent job in exposing both Ferguson and the subject of Rational Expectations. And it rests on the Quantity Theory of Money too!

Joan Robinson reports that Kalecki once announced that “I have found out what economics is; it is the science of confusing stocks with flows” (see Robinson, “Shedding Darkness”, Cambridge Journal of Economics, 6 (1982), 295-6). She adds that “it is this confusion that has kept the Quantity Theory of Money alive until today. By applying V, velocity of circulation, that is turnover say per week or per year, to M, the stock of money used in transactions in a given market, we arrive at the flow of transactions in the market concerned”. She then goes on to point out that there is a mystery about the formula. “MV is the flow of transactions per unit time in terms of whatever currency is used for these transactions, but what is the unit represented by MV/P-transactions in real terms?”

Joan Robinson’s question hits the nail on the head. If you can’t name the unit then scrap the formula. And that’s before we get to serious economic objections!

I understand that the expansion of fiat money has not created severe inflation in the price of goods or services but hasn’t it created very severe inflation in asset prices? I guess that is because the money is in the hands of the wealthy who invest the money rather than spending it. My impression is that a glut of money has allowed people to borrow to speculate in asset price bubbles (such as the housing bubble up to 2007). Didn’t the attempts to revive the Japanese economy by QE just lead to the money leaving Japan and being misinvested in inflating the housing bubbles of the USA, UK, Ireland, Spain etc. Asset price bubbles also seem to make the financial services industry artifactually much more lucrative than it would be if there were not such boom bust asset price cycles. I wonder whether the oversized financial services industry is the biggest cost to society to come from expanding fiat money.

“Where is Keynes when we really need him?” Very fitting question to the latest post of Bill. The newest Hedgehog Review from the Institute for Advanced Studies in Culture ist now online available. A must read is “The Great Mortification: Economists’ Responses to the Crisis of 2007-(and counting)” A devastating critic from a sociologist perspective. A quote …

http://www.iasc-culture.org/publications_article_2010_summer_mirowski.php

Brianovitch: “She then goes on to point out that there is a mystery about the formula. “MV is the flow of transactions per unit time in terms of whatever currency is used for these transactions, but what is the unit represented by MV/P-transactions in real terms?”

“Joan Robinson’s question hits the nail on the head. If you can’t name the unit then scrap the formula. And that’s before we get to serious economic objections!”

We could apply this principle to physics, as well. What is the unit represented by ma in real terms? 😉

In fact, the equation, F = ma , is a definition of force. Eddington rephrased Newton’s First Law of Motion as, “A body will remain in a state of rest or uniform motion, except inasmuch as it doesn’t.” 😉

stone: “My impression is that a glut of money has allowed people to borrow to speculate in asset price bubbles (such as the housing bubble up to 2007). “

I was just thinking along similar lines – I am guessing that variable rate mortgages, homeownership, and council tax, were all monetarist inventions to help monetary policy work in controlling inflation, and also to ensure housing stock was kept under repair. It seems it may have back-fired, as ‘they’ made investing in housing so easy that, that is all the banks and others invest in now.

Council Tax (only paying rates on property when someone actually lives there) means that owning additional houses for investment has become too easy.

I would charge a monthly tax on all residential property where no-one is paying council tax. That would make the investment much less attractive, and so deflate the housing bubble. More people would then be able to buy or rent homes.

Charlie

Anas Jalil: “Ferguson uses Napoleon as one of the example, how a war was lost not because of French did not have an excellent army, but merely because the French had lost Mr Bond’s confidence.”

Right! That explains why the South won the U. S. Civil War. Mr. Bond charged the North too much interest. Oh, wait! 😉 Lincoln told Mr. Bond to go jump in the lake, and issued Greenbacks.

Dear Min,

That precisely what been written by JK Galbraith.

Ferguson is trying to assert the superiority of Mr Bond but JK Galbraith say the govt can just f*cking ignore the bond market if it chooses to and US govt had many time did that.

“What is the unit represented by ma in real terms?”

You seem to have worked that one out. Now do it for MV/P. And the Quantity Theory of Money is not Boyle’s Law either.

You seem to have worked that one out. Now do it for MV/P. And the Quantity Theory of Money is not Boyle’s Law either.

Well …. let’s see …. “M” and “V” would both be in currency units, so those would cancel out …. so the unit for “MV/P” would be the same as the unit for “V” …. transactions per unit time?

Ken

On Tech Analysis, don’t be totally dismissive of the ‘wiggles’……

I’ve always thought it was voodoo, but I may be open to reconsidering if you can point me to a good source that explains why the “random walkers” are wrong. Preferably a source that’s not trying to sell me software…. 😉

Ken

Ken,

Better get yourself into Physics 101 and bone up on units, time, and dimensions. As Joan Robinson points out : “MV is the flow of transactions per unit time in terms of whatever currency is used for these transactions”. Now try dividing by P and applying that to transactions … and you get what?. But isn’t Joan Robinson’s point about the confusing of stocks and flows? Isn’t it time to dispose of the Quantity Theory of Money and get down to proper macroeconomics?

Better get yourself into Physics 101 and bone up on units, time, and dimensions.

MV/P –> (Currency Units) * (transactions/unit time)/(Currency Units) –> transactions/unit time. QED.

Whether that’s of any use or not is a different question ….

Ken

Bill,

Actually I had a quick look at the original Sargent’s RATEX article you mentioned. It also refers to hyperinflation in Poland circa 1923. The Sargent’s article is full of oversimplifications. In fact the history was much more convoluted and quite fascinating as the Poles fought the hyperinflation without practical help from other countries – and it was caused by external and domestic policy factors.

There is a book written in Polish and publish by the National Bank of Poland which describes what happened then in a great detail:

REMOVE_THIS_www.nbp.pl/publikacje/historia/grabski_ksiazka.pdf

Productive capacities were clearly breached by aggregate demand during the hyperinflation period what was a consequence of restoration of independence in 1918 and the war with Bolshevik Russia in 1920. Hyperinflation in Poland was to some extent ignited by the same phenomenon in Germany.

The only clear “rational expectations”- related element in fight against inflation was that people switched to Polish Marka once the exchange rates to other currencies were stabilised due to the Treasury intervention. People were rational – they didn’t want to lose on exchange rates moving against them.

The rest of the reforms were mainly systemic and fiscal – related to reducing budget deficits covered previously by printing massive amounts of money and increasing taxes. Then Polish Zloty was introduced. The disinflation period was characterised by a recession. The same happened in the early 1990-ties and again in 2003.

Poland has a long and successful history of disinflations…

Daer Brianovitch and Ken,

my favourite quotations from Joan Robinson;

“I don’t know mathematics, therefore I have to think”

and

“The purpose of studying economics is not to acquire a set of ready-made answers to economic questions, but to learn how to avoid being deceived by economists.”

Cheers

Anas

That’s interesting Anas. But those are still the units of MV/P. Narrow question …. narrow answer. 😉 I’m not pretending to know what it means – if anything.

Ken

Dear Bill,

It is very interesting for me to read MMT against an historical background – am sure many of your commentators have browsed http://michael-hudson.com/2010/07/entrepreneurs-from-the-near-eastern-takeoff-to-the-roman-collapse/ It reminded me once again that underlying everything is human nature, and that hasn’t changed.

Am always a little surprised to see within the tableau how unimaginative and conditioned human beings are in what they pursue, in their existence: obviously I should stick to more ‘rational expectations’ – but true to my nature, live on in hope. To qualify this I should say that in my experience, I believe what human beings are looking for is within them; not without.

It also reminded me of the hope born of the gregarian, agrarian, industrial, technological and informational revolutions, prophetic in their time, but subject to the same exigencies of human nature. As in your recent post Myths about pay and value these revolutions and evolutions in economics and other human sciences have not necessarily resulted in a more peaceful, humane and enlightened world with thriving social values.

In this sense I believe MMT is a relevant aspect of an evolution in economics, but it is human nature that needs to find peace with itself necessary to coexistence, before things can really change.

To this end, each day is a new day, and an in the moment opportunity to make sure the tableau of our own lives at least – is something with which our heart is happy! (Mind by its own nature, is always restless and never content)!

Cheers …

jrbarch.

“It is true that the Great Depression only really ended with the onset of the Second World War. That was because the level of fiscal intervention reached a sufficient level to drive aggregate demand growth strong enough to fully absorb the growth in real capacity. The commitment to war overcame all the conservative attacks on deficits etc.”

How about how much supply was destroyed?

Ken: “MV/P -> (Currency Units) * (transactions/unit time)/(Currency Units) -> transactions/unit time. QED.

Whether that’s of any use or not is a different question ….”

I have (Currency Units) * (transactions per unit time)/(Currency Units per transaction or widget) => What?

As Joan Robinson points out: this is shedding darkness.

I have (Currency Units) * (transactions per unit time)/(Currency Units per transaction or widget) => What?

OK — doing it your way we come up with transactions squared per unit time. But, when doing this sort of dimensional analysis, things like “transactions” are generally considered dimensionless … we set the “unit” equal to 1. So, doing it either your way or mine, the units of MV/P come out to be “inverse time” (1/(unit time)). What does that mean? I don’t know 🙂

As Joan Robinson points out: this is shedding darkness.

Yup.

But the question of “what are the units of MV/P” has been answered. For whatever that’s worth. Probably not much. Not a burning question in my mind…. but it’s easy to answer. Unlike the more interesting questions being discussed here! Maybe those are trivial to answer as well, if you buy into all the assumptions of MMT. I’m getting there … maybe ….slowly. Still have concerns.

Ken

Ken: I guess you must do it your way. I prefer to do it the way Joan Robinson does it, as that doesn’t confuse stocks and flows, and apples and pears …

What’s funny is that we mostly seem to be in agreement. I have no idea what we’re even arguing about! If you ever happen to be in Portland OR, hit me up and I’ll buy you a craft brewed Oregon beer. Or two. Cheers!

Ken

Gents, do you maybe have a link to this paper?

Sergei: for “Shedding Darkness” see http://cje.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/pdf_extract/6/3/295

Ken: We seem to agree that the Quantity Theory is junk economics. You write the dimension of V as [t^-1], Joan Robinson writes the dimension of V as [qt^-1] where [q] is the dimension of ‘transactions’. That explains the difference. Many mainstream textbooks use the same approach as you. JR asks an awkward question, since quantities demanded usually have dimension [qt^-1]. She once asked ‘how is Capital measured?’, and this caused uproar. I don’t think we should let this cause a storm in a teacup. I’ll settle for a beer.

Ken:

Robinson – “…transactions in real terms?”

Of course you can reduce MV/P for financial flows, the point is what is the equivalent in the real/productive economy? What is the unit dimension? The whole point of the monetary system is to represent real economic activity – so Joan Robinson’s point is that there is no corresponding Quantity Theory of “X” – is it Labor, is it Time, what is the Real unit?

It is a very piercing insight.

All I see is mouthpieces like Ferguson manipulating people’s expectations with their irrational scaremongering.

It seems they are afraid of letting people develop their own ‘rational’ expectations. How wedded to RATEX theory can they really be?

I have nothing personal against Ferguson – I just thought that this article from Daily Mail is interesting

The history man and fatwa girl: How will David Cameron take news that think-tank guru Niall Ferguson has deserted wife Sue Douglas for Somali feminist?

Read more: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1249095/The-history-man-fatwa-girl-How-David-Cameron-news-think-tank-guru-Niall-Ferguson-deserted-wife-Sue-Douglas-Somali-feminist.html#ixzz0uRivoj6P

Bill: This is a playback of the so-called rational expectations literature which Ferguson proudly cites as his authority. The problem is that the theory is defunct

Evolutionist David Sloan Wilson, Economics and Evolution as Different Paradigms XII: Behavioral Economics, or will the real Homo sapiens please stand up?

“Of course you can reduce MV/P for financial flows, the point is what is the equivalent in the real/productive economy? What is the unit dimension? The whole point of the monetary system is to represent real economic activity – so Joan Robinson’s point is that there is no corresponding Quantity Theory of “X” – is it Labor, is it Time, what is the Real unit?

It is a very piercing insight.”

MV = PQ

Q = MV/P = real output / time

Eg “amount of valuable stuff created per year”.

The only way you could measure it exactly would be to list everything of value that was created.

To say it has no “units” is not really an incredible insight in my book. This is a fundamental problem in economics, how is “value” measured? Money, time, labour, “use-value”, “price-value”, “utility”, the list goes on without satisfactory answer.

But that doesn’t mean that real output is not a valid or useful concept. I bet that no-one can give me an absolutely watertight definition of what it means if someone is “bald”. Does this mean that there is no such thing as baldness?

By the way, thanks for post Bill, always interesting and provocative. A couple of comments.

1) You say: “Does anyone believe that households are always rational and perfectly informed about all current and future events?”

You have focused on the wider “rational expectations” theory, and all the non-sense that follows. But Ferguson is talking specifically about inflationary expectations (and never suggested that they need to be perfect), so why not specifically address that.

To turn the question back around: Does anyone deny that people do hold expectations about future inflation?

Ask most people in Australia what they think inflation is likely to be and they will probably say around 2% to 3%. Many people expect a 2 or 3% payrise every year as a matter of course, just to cover inflation. If you talk to someone who is expecting to get a payrise next year because they have become more experienced / capable at their job and they get 2.5% they will probably walk away disappointed.

2) Regarding you graphs, on your vertical axis you have plotted “annual CHANGE in US inflation”. So you have used the second derivative or differential of price? Why? Why not show a plot of what the quantity theory actually is, at least give it an honest hearing?

It should be: Change in price (ie inflation) Vs change in money base.

Or, to be complete: [Inflation] Vs [change in money supply – change in output]

Cheers.

Ferguson: People are nervous of world war-sized deficits when there isn’t a war to justify them.

Is this guy asleep?

Hello, it’s the “GLOBAL WAR ON TERROR,” and the bill, which is being put on the deficit tab, is huge. Ferguson hasn’t even got his facts right.

I really enjoy your work. Thanks for the intelligent writing.

Brianovitch: “You seem to have worked that one out. Now do it for MV/P. And the Quantity Theory of Money is not Boyle’s Law either.”

I suppose that the point is that the units are arbitrary or conventional. For instance, suppose that I buy a power bar for $3 one day, and buy 2 gals of gasoline for $6 the next. On the second day, is the price $3, or $6, or $1? Whatever it is depends upon what units we use to measure buying gasoline, and that is up to us. We may have P = $3 and Q = 3, or P = $4.50 and Q = 2, or P = $1.50 and Q = 6, etc. It is up to us.

To continue the thought experiment:

In the next two day period, suppose that the price of gasoline doubles, and that I spend the same amount of money, but buy half as much gas. Then, using the same units as before, instead of P = $3 and Q = 3, we have P = $4.50 and Q = 2, or instead of P = $4.50 and Q = 2, we have P = $6 and Q = 1.5, or instead of P = $1.50 and Q = 6, we have P = $2.57 and Q = 3.5. Note that the percentage change in P depends upon the choice of units we decided upon. That fact gives us pause, doesn’t it?

Min: “…depends upon the choice of units we decided upon. That fact gives us pause, doesn’t it?”

Indeed. In High-School Physics we have to learn quickly that we are not engaged in manipulating (high school) algebra and arithmetic; we have to learn all about dimensions and units in order to have physics. We have to learn the sense of (for example) Force = Mass times Acceleration and Linear Momentum = Mass times Velocity. I take it that Joan Robinson’s reference to the ‘mystery’ in the Quantity Theory of Money MV = PQ is that it just doesn’t make sense. If the stock of money M has dimension [m], and Q is the real output of the (single good) economy with dimension [qt^-1], then P is money per unit of the good and has dimension [mq^-1]. But what is the dimension of V? Most mainstream text books describe this as the velocity of ‘circulation of money’ indicating the average number of times a unit of money circulates over a period of time; they give V a dimension of [t^-1]. So MV has dimension [m][t^-1] = [mt^-1] and PQ has dimension[mq^-1][qt^-1] = [mt^-1], making the LHS and RHS agree in dimensional terms. By such simplicities the mainstream can rescue the theory.

But am I the only person other than Joan Robinson who is disturbed by this? If MV has dimension [mt^-1] then it’s a flow and can be seen (in terms of SFC accounting) as DeltaM, and we should prefer to write the Quantity Theory as DeltaM = PQ. Can V in the Theory really have dimension [t^-1]? We know V in the expression for Linear Momentum has dimension [dt^-1] where [d] is the dimension of distance travelled. Shouldn’t the dimension of V in the Quantity Theory be something like [qt^-1]? Joan Robinson writes : “MV is the flow of transactions per unit of time …” not “the average number of times a unit of money circulates over a period of time”. If so, then the LHS would not equal the RHS; we have [m][qt^-1] not equal to [mt^-1].

If one takes the mainstream view that the dimension of V is [t^-1], then one can merrily proceed to use it to ‘justify’ monetarism, Gesellian currency taxes … anything. But there is something fishy about it, and Joan Robinson has indicated something about the smell of the term ‘transactions’. She has a habit of raising awkward questions, and I was hoping that some expert on dimensional analysis in economics would throw some light on it.

@brianovitch

Thank you! Up till your comment I was confused by this talk of units and dimensions, but you made it clear for me. And no, you and Joan are not the only one’s disturbed.

The mistake that several earlier posters made (and that Joan is pointing out) is thinking that you can just slide between stocks and flows by saying ‘average number of some event over time’.

The best analogy that brings out the dodginess I could come up with was the ‘quantity theory of roads’ identity

Total kilometres of road (M) * average number of times a year each kilometre of road is driven on (V)

*is by definition equal to*

Length of a trip (P) * Number of trips made (Q)

Studies have shown that the number of times each kilometre of road is driven on is reasonably constant and determined by structural factors, and the efficient driver hypothesis establishes that all the trips that can or need to be made are being made. Therefore, building more roads will increase the length of trips, as a simple mathematical identity.

Brianovitch: “In High-School Physics we have to learn quickly that we are not engaged in manipulating (high school) algebra and arithmetic; we have to learn all about dimensions and units in order to have physics. We have to learn the sense of (for example) Force = Mass times Acceleration and Linear Momentum = Mass times Velocity. I take it that Joan Robinson’s reference to the ‘mystery’ in the Quantity Theory of Money MV = PQ is that it just doesn’t make sense.”

Now that I think about it, P and Q should be vectors, no? Each commodity has a different dimension.

I wrote: “Now that I think about it, P and Q should be vectors, no? Each commodity has a different dimension.”

Or, equivalently,

MV = Sum(P(i)Q(i))

where i stands for a good or service. (I don’t do sigma.)

@Min

You are quite right. It would be hopeless to try adding apples, pears and X-ray machines. But you can add their ‘values’. (The Quantity of Money formula seems to assume an idealized single good economy). MMT economists need to value their Stocks of Assets in tables in terms of some currency (say with dimension [m]), whereas the Transaction Matrices of flows will be expressed in terms of a flow of currency per some unit time (say [mt^-1]). Accumulating the flows into the stocks needs to take the length of the period of time into account; thus stock + flow has dimension [m] + [t][mt^-1] = [m] + [m] = [m]. As an aside, Walrasian economists seem to model an n-commodity system on the (n-1) unit sphere, implicity using a normalized vector giving a separate dimension for each commodity’s price.

Bill makes the point that Niall Ferguson can’t be taken seriously on the subject of economics. But I wonder how seriously one can take him in his role as a historian? Tim Congdon cannot be regarded as a friend of MMT, but he’s done a fairly good job in pointing out the inadequacies of Ferguson’s new hagiography of the Warburgs. He describes Ferguson’s thesis as “poppycock”. See the review in this week’s TLS :

http://entertainment.timesonline.co.uk/tol/arts_and_entertainment/the_tls/article7164546.ece

After some absence and seclusion to work and reflect on some new ideas, I return to see the quality of some comments by Billyblog community memebers vastly improved with some rigorous analysis on stocks and flows. Very encouraging…….However, a unit cannot be independent of its relation with its occurrence.