I have received several E-mails over the last few weeks that suggest that the economics…

They’re just sticking a finger in the air and guessing

The policy balance continues to be wrong in the US and elsewhere. While central banks are politically “free” to change their policy settings, fiscal authorities appear to be hamstrung by some absurd politics at present. In the midst of economic pain and suffering, governments (and oppositions) are proposing policy settings which will worsen that pain. They then sell the message that more pain will deliver good outcomes to their electorates without having a clue whether that it true or not. In doing so they defy all empirical experience and rely on defunct and failed theory for their authority. It is as if “They’re just sticking a finger in the air and guessing”. The other tragedy in all of this is that the monetary policy changes that have been invoked are largely ineffective in terms of expanding aggregate demand. This is in contradistinction to fiscal policy which is very effective in expanding spending, if used properly. Of-course, this policy mayhem is just a reflection of the dominance of the neo-liberal paradigm which actively eschews effective government involvement in the economy.

As I discussed in yesterday’s blog – When facts get in the way of the story – the US economy is now slowing and shedding net jobs again. This was to be expected given the impact of the fiscal stimulus is now waning. Consumer spending is very weak and unresponsive to the easing of monetary policy.

The service industries which often lead the recovery are now stagnating. In previous recoveries, once growth resumes it builds on itself. This time that is not happening.

I also noted that the major political focus is on implementing fiscal austerity as various commentators seek to demonise the budget deficit and debt figures.

What these commentators do not seem to understand is that when an economy is in this sort of state and is situated in a world that is globally still largely recessed the only way to get out of this malaise is to use fiscal policy to support demand (spending) and provide some basis for firms to keep producing and hiring.

Some commentators do understand this but still advocate fiscal austerity because they know that the costs will be borne by the workers and it will allow them to clear away a raft of worker protections and social security safety nets. So some advocates of austerity are clearly using it to further their own self-interest to clear the way for them to get a larger share of the real economic bounty. The problem is that the bounty will be significantly diminished for years to come as a result.

While the US is slowing and will slow considerably more without extra fiscal support, other nations are starting to see the ugly side of the austerity drive.

There was a fairly graphic account in the New York Times yesterday (August 9, 2010) – Britain Reels as Austerity Cuts Begin – which spawned the title of today’s blog.

The following picture of a bankrupt business in Coventry is representative of what is starting to happen in English cities as aggregate demand contracts due to the harsh austerity measures introduced by the new British government.

The article said that:

Last month, the British government abolished the U.K. Film Council, the Health Protection Agency and dozens of other groups that regulate, advise and distribute money in the arts, health care, industry and other areas. … But it was just a tiny taste of what was to come.

Like a shipwrecked sailor on a starvation diet, the new British coalition government is preparing to shrink down to its bare bones as it cuts expenditures by $130 billion over the next five years and drastically scales back its responsibilities. The result, said the Institute for Fiscal Studies, a research group, will be “the longest, deepest sustained period of cuts to public services spending” since World War II.

The Government is hoping for an export led recovery. It will not happen.

The cuts announced in June ($10 billion from 2010-11 budget) are starting to bite. The article reports that:

Oxfordshire, facing a nearly $1 million trim in its road safety budget, has been forced to shut down all of its 161 traffic speed cameras.

Nottinghamshire plans to close three recycling facilities and some of its day care centers. The city of Coventry, which already cut spending in January, is trying to find $5.6 million more to cut from its current child services budget.

The next cuts will be announced in October and 600,000 public-sector jobs are to go. Cuts are occurring in education (the long-run productivity growth engine), health care and personal care services.

In a blog last week – The old line back to free market ideology still intact – I outlined the argument made by the CEO of the Dallas Federal Reserve Bank, Richard W. Fisher in his recent speech – Random Refereeing: How Uncertainty Hinders Economic Growth.

His speech continued to air the view that is now commonplace in the public debate that government policy is now making the recession worse and things would be better if the government just set some rules and let the market rip.

He said:

I have ascribed the economy’s slow growth pathology to what I call “random refereeing” – the current predilection of government to rewrite the rules in the middle of the game of recovery. Businesses and consumers are being confronted with so many potential changes in the taxes and regulations that govern their behavior that they are uncertain about how to proceed downfield. Awaiting clearer signals from the referees that are the nation’s fiscal authorities and regulators, they have gone into a defensive crouch.

At the time I said that much of the “uncertainty” is being driven by the fact that the government stimulus is now being withdrawn and austerity programs which are cutting peoples’ incomes and pensions are now being pursued with vigour. Fisher didn’t mention that.

The Coventry City Council leader told the New York Times that the austerity programs are being implemented in an arbitrary manner. He said that “It feels like they’re just sticking a finger in the air and guessing”.

He explained that the austerity forced them to abandon a multimillion-pound program “to build new schools and refurbish crumbling old ones in Coventry – had come so abruptly that carefully wrought plans and partnerships had to be torn up overnight”:

… It’s impossible to plan … We believe in trying to plan our budget for three years, particularly in order to give our voluntary and private-sector partners some stability. But we can’t do that at the moment. We haven’t a clue.

That sounds like real uncertainty to me. The uncertainty that Fisher and his Ricardian Equivalence-ilk claim to be important (that is, the fear of higher taxe rates to pay the deficits back) is without any empirical support.

But when contracts are abandoned and orders start to dwindle and inventory starts to remain unsold that is real uncertainty – the type that leads firms to lay off workers and cut back on production. It is the start of a downward spending spiral driven by the multiplier. Please read my blog – Spending multipliers – for more discussion on this point.

Once this downward spiral gathers pace and the uncertainty becomes entrenched then people start losing their homes and the malaise generalises. Only fiscal intervention can stop this sort of dynamic.

So when you need fiscal policy – you get monetary policy

Yesterday, the Federal Open Market Committee of the US Federal Reserve announced that it was not intending to reduce the size of its balance sheet.

While they are intending to release a technical note “providing operational details on how it will carry out these transactions” the message is very clear.

They are viewing the economic data in the same way as I describe above and are acknowledging that more expansionary aggregate policy is required. The problem is that monetary policy is the only option left in the US to try to stimulate aggregate demand. That is a problem because it will not be an effective intervention.

In the press release, the FOMC said:

The Committee will maintain the target range for the federal funds rate at 0 to 1/4 percent and … To help support the economic recovery in a context of price stability, the Committee will keep constant the Federal Reserve’s holdings of securities at their current level by reinvesting principal payments from agency debt and agency mortgage-backed securities in longer-term Treasury securities. The Committee will continue to roll over the Federal Reserve’s holdings of Treasury securities as they mature …

So what this means is that instead of reducing the assets they currently hold as they mature the central bank is holding its overall assets and changing the composition of them to include more government debt.

This graph shows what economists call an announcement effect. The graph is of the Dow Industrials index for August 10, 2010 and you can see the spike and overall market reaction that followed the announcement by the Open Market Committee of the US Federal Reserve at 14:15. Who says that the markets rule?

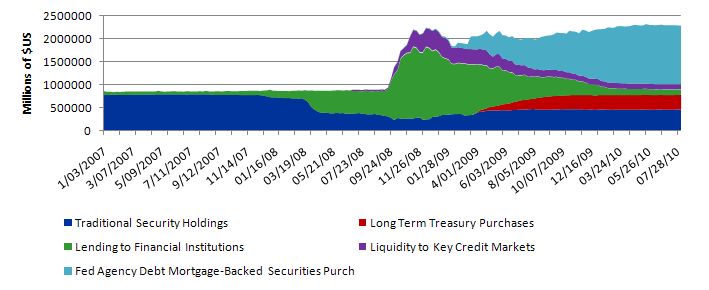

The next graph shows the evolution of the US Federal Reserve bank’s balance sheet. You can see that as the crisis has unfolded the different policy interventions have come and gone. The data is available from the Federal Reserve Bank Cleveland.

The three policy responses were in the areas of lending to financial institutions, providing liquidity to key credit markets and purchasing longer-term securities. At the time, the expansion of the balance sheet and the changing composition over time was referred to as “credit easing” by Bernanke.

These policies included the Term Auction Facility (TAF) announced in December 2007, the currency swap lines with other central banks; the Term Securities Lending Facilities (TSLF) and the Primary Dealer Credit Facility (PDCF). These interventions were gradually scaled back and you can see have very little residual impact on the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet.

These policies all aimed to provide liquidity to financial institutions on the mistaken understanding that the lack of borrowing reflected a supply-side constraint. It was clear that the demand for credit was flat and no amount of liquidity would change that but the central bank seemed blind to that reality.

The Federal Reserve then decided that the problem was in the non-bank markets where companies gained access to short- and long-term funds. The Federal Reserve targetted the money market mutual funds by providing finance to banks to fund “the purchase of asset-backed commercial paper from the money funds” which had taken losses at the time that Lehmans collapsed (Source).

They then chose to support the commercial paper market (short-term debt instruments are traded) by introducing the Commercial Paper Funding Facility (CPFF), which “purchases 3-month unsecured and asset-backed commercial paper that carries credit ratings in the top tier” thereby reducing any roll-over risk.

In late 2008, the Federal Reserve announced its Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility (TALF), which further proposed to lend money “against asset-backed securities that are backed by student, auto, credit card, and SBA loans”.

There were other measures. You can read an account of this policy evolution from HERE.

The third set of policy tools employed by the Federal Reserve bank focused on purchasing longer-term securities. First they purchased “the direct obligations of the housing-related government-sponsored enterprises” and later they generalised this to purchase mortgage-backed securities”.

Yesterday’s announcement now extends the spread of their policy net to include purchasing treasury securities (that is, public debt).

One New York Times commentator (Catherine Rampell) said of this intention:

More controversially, the committee said it would maintain the Fed’s unusually expansive balance sheet by “reinvesting principal payments from agency debt and agency mortgage-backed securities in longer-term Treasury securities.” In other words, rather than letting some of the Fed’s more aggressive policy initiatives end as planned, the committee decided to keep pumping money into the economy by investing in longer-maturity debt.

Which is inaccurate because they are not “pumping money into the economy” at all. This error was also made by the CNBC finance commentator Steve Liesman in this interview. Incidentally, the Rampell was also interviewed on the same segment so probably got the idea from Liesman.

Liesman said that this “monumental Fed decision” was equivalent to the “Fed printing the money to finance the country’s debt”. This is clearly incorrect. From the perspective of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), the reserve balances that commercial banks hold at the central bank are equivalent to one day government debt instruments.

The latest plan by the Federal Reserve merely involves them changing the duration of the outstanding balances. All that is happening is that the US treasury security holders are swapping treasury bonds for reserve balances.

There is a lot of confusion as to whether this move represents more quantitative easing. The UK Guardian called the move “QE lite” in this article – Federal Reserve resorts to ‘QE lite’ in face of slowing US recovery – published after the announcement was made.

The Guardian said:

The US Federal Reserve tonight took a cautious step towards pumping extra liquidity into the financial system through an operation described as a “light” version of quantitative easing in response to a slowdown in the pace of America’s economic recovery … in a measure intended to serve as a stimulus to economic activity, the central bank said it intends to reinvest the proceeds of its maturing holdings of mortgage-backed securities by pumping the funds into Treasury bonds. The keenly anticipated adjustment in policy has been dubbed “lite” as a lighter version of the type of quantitative easing embarked upon by the Treasury in Britain.

So apparently “full QE” is when the central bank purchases existing assets held by the private sector and in doing so adds bank reserves in return and expands its balance sheet. The current plan is to hold the balance sheet at its present size but change the composition of assets being held.

One commentator quoted by the Guardian said “that unless the American economy shows tangible signs of improvement, the Fed could step up its action with fully blown quantitative easing – expansion of the money supply – by Christmas.”

Again this is not an accurate way of representing the situation. The addition of reserves is a $ for $ addition to the “money supply” as defined. But the mainstream economists think this will multiply out into a much large increase in the broad money measures.

It is clear that adding reserves has not had much effect on the broader money supply measures anyway. Please read my blog – Money multiplier – missing feared dead – for more discussion on this point.

To understand what quantitative easing is please read my introductory blog – Quantitative easing 101 – for more discussion.

To repeat the main message of that blog, quantitative easing involves the central bank buying bonds (or other bank assets) in exchange for deposits made by the central bank in the commercial banking system – that is, crediting their reserve accounts.

The aim is to create excess reserves which mainstream economists (erroneously) think will then be loaned to chase a positive rate of return. So the central bank exchanges non- or low interest-bearing assets (which we might simply think of as reserve balances in the commercial banks) for higher yielding and longer term assets (securities).

So quantitative easing is just an accounting adjustment in the various accounts to reflect the asset exchange. The commercial banks get a new deposit (central bank funds) and they reduce their holdings of the asset they sell.

Proponents of quantitative easing claim it adds liquidity to a system where lending by commercial banks is seemingly frozen because of a lack of reserves in the banking system overall. It is commonly claimed that it involves “printing money” to ease a “cash-starved” system. That is an unfortunate and misleading representation.

Thinking of this as “printing money” is very misleading. All transactions between the Government sector (Treasury and Central Bank) and the non-government sector involve the creation and destruction of net financial assets denominated in the currency of issue. Typically, when the Government buys something from the non-government sector they just credit a bank account somewhere – that is, numbers denoting the size of the transaction appear electronically in the banking system.

Crucially, quantitative easing requires the short-term interest rate to be at zero or close to it. Otherwise, the central bank would not be able to maintain control of a positive interest rate target because the excess reserves would invoke a competitive process in the interbank market which would effectively drive the interest rate down.

Does quantitative easing work? The mainstream belief in QE is based on the erroneous idea that the banks need reserves before they can lend and that quantititative easing provides those reserves. That is a major misrepresentation of the way the banking system actually operates. But the mainstream position asserts (wrongly) that banks only lend if they have prior reserves.

The illusion is that a bank is an institution that accepts deposits to build up reserves and then on-lends them at a margin to make money. The conceptualisation suggests that if it doesn’t have adequate reserves then it cannot lend. So the presupposition is that by adding to bank reserves, quantitative easing will help lending.

This also ties in with the erroneous “crowding out” claims that are the centrepiece of the mainstream macroeconomics attacks on fiscal policy use.

For example, New York Times commentator, Sewell Chan wrote in his article after the FOMC announcement – Fed Move on Debt Signals Concern About Economy – that:

In buying new Treasury securities of at least $10 billion a month – a small fraction of the roughly $700 billion in Treasury debt the Fed holds – the central bank will help keep money readily available in the financial markets.

There is no more “money readily available” in the financial markets than there was previously.

These conceptions are completely incorrect depictions of how banks operate and how credit is provided. Bank lending is not “reserve constrained”. Banks lend to any credit worthy customer they can find and then worry about their reserve positions afterwards.

If they are short of reserves (their reserve accounts have to be in positive balance each day and in some countries central banks require certain ratios to be maintained) then they borrow from each other in the interbank market or, ultimately, they will borrow from the central bank through the so-called discount window. They are reluctant to use the latter facility because it carries a penalty (higher interest cost).

The point is that building bank reserves will not increase the bank’s capacity to lend. Loans create deposits which generate reserves.

Please read the following blogs – Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary – for further discussion.

The reason that the commercial banks are currently not lending much is because they are not convinced there are credit worthy customers on their doorstep. In the current climate the assessment of what is credit worthy has become very strict compared to the lax days as the top of the boom approached.

The major formal constraints on bank lending (other than a stream of credit worthy customers) are expressed in the capital adequacy requirements set by the Bank of International Settlements (BIS) which is the central bank to the central bankers. They relate to asset quality and required capital that the banks must hold. These requirements manifest in the lending rates that the banks charge customers. Bank lending is never constrained by lack of reserves.

So when the central bank is conducting quantitative easing all it is doing is buying one type of financial asset (private holdings of bonds, company paper) and exchanging it for another (reserve balances at the BOE). The net financial assets in the private sector are in fact unchanged although the portfolio composition of those assets is altered (maturity substitution) which changes yields and returns.

In terms of changing portfolio compositions, quantitative easing increases central bank demand for “long maturity” assets held in the private sector which reduces interest rates at the longer end of the yield curve. These are traditionally thought of as the investment rates. This might increase aggregate demand given the cost of investment funds is likely to drop. But on the other hand, the lower rates reduce the interest-income of savers who will reduce consumption (demand) accordingly.

How these opposing effects balance out is unclear. The central banks certainly don’t know! They are “just sticking a finger in the air and guessing”. Overall, this uncertainty points to the problems involved in using monetary policy to stimulate (or contract) the economy. It is a blunt policy instrument with ambiguous impacts.

New York Times commentator Sewell Chan wrote:

That action may put downward pressure on long-term interest rates and make it easier for companies and people to borrow. For consumers, it means that mortgage rates are likely to remain at record lows for some time.

It doesn’t make it easier to borrow. It reduces the costs of borrowing. But if there is very little aggregate demand growth in the economy then firms will be unlikely to desire to expand production. Hence they are unlikely to expand borrowing very much even though the funds are cheaper. There may be some marginal positive benefits only.

Some commentators are still stuck in the Quantity Theory of Money inflationary mindset. The NYT article by Sewell Chan quoted an economics professor from the University of Michigan (Christopher L. House – students take note – avoid his classes as you will be mislead by what you “learn”). The discussion was in terms of the other “option available to the Fed” which “is to lower the interest rate (now 0.25 percent) it pays on the roughly $1 trillion in reserves that banks hold at the Fed”.

House said the “could be helpful” but “carries some risk” because if:

… they were to simultaneously lower the rate to zero while leaving $1 trillion in reserves in the banking system, they would have a lot of reason to worry about inflation …

Please read the following blogs – Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary – for further discussion of why you should avoid House’s classes if you are intending to study economics at the University of Michigan.

CNBC commentator Steve Liesman said that this was a “watershed” move by the Federal Reserve because they are now redefining their balance sheet levels and we will judge expansion or contraction as movements away from the 2.4 trillion balance sheet position from now on rather than seeing the current balance sheet as a crisis and hence temporary phenomenon.

That should rock some of the inflationistas out there and cause them some sleepless nights. My recommendation – read a nice crime thriller before you go to bed and you will sleep better. When you wake up each day there will be no rampant inflation and that should get you through the day.

The Guardian quoted another private bank economist who expresses a view that is commonly held:

The initial response of the equity market, I believe, will be reversed as soon as investors realise that the Fed only took a baby step when the economy needs a giant leap.

The giant leave the US economy needs will never be found in monetary policy. How long does it take for us to realise that adding monetary base to the system (adding bank reserves) does very little to stimulate the economy?

It is clear that Bernanke and Co. think that monetary policy is the main game in town which just continues the neo-liberal dominance. Bernanke is also on record as wanting the budget deficit reduced.

While the Federal Reserve move certainly holds down long-term interest rates (in the segment the asset purchases are being made) at slightly lower levels than otherwise which may be beneficial at the margin the US economy desperately needs some direct spending injected. That can only come at present from fiscal policy.

There is no other game in town. Sorry!

Conclusion

I thought this reflection in the New York Times – The Fed Is Worried posted late in the afternoon was telling:

Addendum, 5:30 p.m.: I see that the Fed’s concerns did not seem to have much effect on House Republicans, all but two of whom voted against the very modest stimulus bill that House Democrats passed today. If the Fed is right to be worried, then there is a lot to be said for easier fiscal policy until the threat has passed.

Yes. They’re just sticking a finger in the air and guessing – and are blind to the only game in town. The US economy will continue to suffer as a result.

That is enough for today!

The “stimulus” bill that House Democrats passed today, which will keep some teachers from getting laid off, is being paid for by cutting food stamps. It is not a stimulus bill at all. Obama&Co. are merely moving the deck chairs on the Titanic around. Apparently they believe that hungry children learn better in smaller classes.

P.S. Regarding the title, do you recall which finger it was?

“Sticking a finger in the air” – that’s reminiscent of a phrase used more than once by Bank of England officials in relation to QE: “suck it and see”. If the latter officials by their own admission don’t know what they are doing, it’s a pity they don’t do the decent thing and resign.

Bill,

A question that I hope you will find the time to expand upon:

When a bank makes a loan, it creates money by crediting it to someone’s bank account.

It also creates an asset for itself (the loan), and a liability (the deposit)

When the loan is paid off, the asset disappears, the liability (system wide) disappears,

but the bank now has additional cash/assets in the form of the money used to pay

off the loan.

I assume that bankers rarely, if ever, burn money, so it would seem that the bank

has created permanent new money via the creation of credit.

Is this true/accurate? Is this the right way to view the situation?

Your insight would be greatly appreciated.

Jeff Jensen

Mervyn King has said that the UK recovery was going to take a long time, as the economy restructures away from the consumer to net exports. I don’t object to net exports but why can’t we have a domestic recovery as well? Why does there have to be a choice? I think this must be the government’s idea (Cameron knows alot about history) – it should have died along with the British Empire.

Kind Regards

Charlie

@Jeff ~

The other side of your transaction that you’re seeing as creating new money is the money that came out of the wallet of the person paying off the loan. Yes, the bank has more (“new”) money, but for the macro-economy, it’s still net zero.

Jeff, think of it this way. The bank loans the customer $X and the customer desires it in cash. The bank delivers the customer cash instead of crediting his or her deposit account, or maybe writing a bank check. The bank reduces its cash account, credits the customer’s deposit account, and debits its asset account under loans outstanding. This just moves the amount held previously on the asset side in cash to loans outstanding, a receivable. Later, the customer pays of the loan with $x (plus interest) in cash. The bank debits its cash account and credits it loan account. Again, it is just a switch on the asset side. The bank’s cash account is only richer by the amount of interest after the transaction. This is the gross revenue on the transaction. The $X that came back doesn’t make the bank any richer even though it has more money in the vault.

Now ask where the bank got the cash in the first place. It exchanged bank reserves at the Fed for FR notes in expectation that some customers would desire cash. In the cases that loans are made not involving cash. essentially the same thing happens with reserves as with cash but with reserves directly. It just happens behind the veil in the settlement process at the regional FR bank. The bank’s accounting process is similar, only the cash account is not involved. It’s the bank’s reserve account at the regional FR bank that the bank reserves come out of when the customer writes check on the proceeds of the loan in his or her checking account. When the loan is paid down, for example, with a check drawn on another bank, then the bank’s reserve account gets the reserves that were involved in the loan back. Net zero.

As Benedict@Large says, no new “money.” Either the cash that went out comes back or the reserves that went out come back – plus interest, of course, which the customer had to obtain independently of the loan, e.g., though income, selling assets, or borrowing.

Jeff:

If that loan was paid off using funds that at some point originated from government spending, then new permanent money was created, otherwise the money came from bank money, which required a bank asset (loan) to offset their liability (reserve notes). But the bank did not “create” that net money – but they don’t need to – they just need to make sure they end up holding on to it at the end of the day.

Of course, this is an abstraction as money is fungible and you can’t trace at a micro level where “funds” come from and go to. But it works at the macro level just fine.

Charlie:

The BoE is praying for net exports because that is the only flexible sector left. The government sector is reducing its net spending and the non-government sector is reducing its net spending. So exports is the only variable left.

The non-government sector can’t expand its net spending because it is fundamentally over-extended against no deflating asset prices. One of the reasons for QE is to bring down long term interest rates – because they are used as discount rates against assets. Lower discount rates = higher asset prices usually. And that will continue for a while until people realise they are not getting the income from the assets they used to.

The domestic private UK economy has been built entirely on asset price inflation and borrowing money against that. A bank can lower the quality of its loans if it knows that asset price inflation will protect it against losing money on bad loans. And it can lower the quality some more if it knows it can offload its loan book onto somebody else at a profit (securitisation). Both of those mechanisms are no longer available and so the economic demand for loans has fallen. (There’s a lot of *desire* for loans, but less willingness to lend – hence reduction in economic demand).

So I think at the macro level there has been a fundamental change in the amount of money available in the domestic private economy. Therefore there can’t be a domestic private recovery.

It follows then that the policy makers look to exports to get them out of the hole that the economic theories they hold dear tell them they are in.

Unfortunately that’s the conclusion the rest of the developed world has come to. Which begs the question who is going to be doing the importing?

Neil,

Thanks for the answer to this. The fact that ‘new’ money can only get into the economy through bank lending seems like a problem to me. It seems to limit the options for the economy going forward.

Kind Regards

Charlie