Elephants everywhere

I often read articles that follow their own logic impeccably except they leave the main part of the story out. They ignore the elephant that is staring at them from the corner of the room. In doing so they avoid facing up to uncomfortable realities and just perpetuate the standard myths that characterise economic debate in this neo-liberal era. Some other articles build on this deception and just plain invent things to beguile their readers into thinking they have something important or valid to say. Tomorrow I will review the latest Morgan Stanley briefing (August 25, 2010) which is an example of the latter. But in general the conservative commentators exploit the fact that the general public do not what the debates are in economic theory and thus litter their proselytising with spurious claims while the elephant laughs away in the corner. It is almost comic book stuff except the standard of narrative in most comics is vastly superior to the trash is pumped out daily in the World’s press.

I read an article at the weekend that was published by the UK Observer (August 22, 2010) – Only Keynes’s animal spirits can intoxicate our hung-over economies – which was written by one John Llewellyn who was global chief economist at Lehman Brothers and prior to that head of economic forecasting at the OECD. So not a great pedigree one would say.

He was talking about the meaning of “confidence” and how he learned from his days at Cambridge (from Joan Robinson) that:

“Confidence indicators tell you only about the present,” she said, “and that is not very important.” What Maynard was concerned about, she went on, was “animal spirits” – the optimism of businessmen to borrow and spend today, even though the resulting output can be offered for sale only in a future that is intrinsically unknowable.

That is a basic insight that all non-mainstream economists share – firms will only borrow, produce, employ now if they feel as they will be able to sell the output in the future.

Apparently it took Llewellyn “many years fully take her point” but that he now has “come to appreciate that what Joan was trying to get into my head was, and remains, of fundamental importance”. So:

Every year, households and companies save part of their income. That saving has to be borrowed and spent, otherwise the economy slides into recession. But borrowing has to be paid back, and with interest, so it had better be used to finance investment, rather than mere consumption.

Hence the fundamental significance of animal spirits. As Joan explained, entrepreneurs may be “confident” that their revenues will continue to exceed their costs. But that does not necessarily mean that they will feel sufficiently spirited to expand their capacity. That requires faith that, in the unknowable future, demand will be higher than it is at present.

And I agree with him that this is “broadly the situation in most western economies today” and that “the corporate sector is in no mood to borrow on anything like the scale needed to ensure that the economy’s full rate of saving gets spent”.

So net public spending has to finance that saving or in his words “to ensure that the economy’s full rate of saving gets spent”. The failure of governments to fill that gap left my the private spending pessimism is why we have a recessed global economy.

We hear that it is because of the sub-prime housing market in the US or because the big banks over-extended themselves and lost their capacity to adequately price risk. All of these suspects are financial in nature. A recession is a real phenomenon and can be expressed in terms of lost output growth or lost employment growth or both.

The real economy responds to spending and if the growth in nominal aggregate demand had not fallen then no matter what happened in the financial markets the real economy would have been okay.

Further, and not often mentioned is the fact that many of the so-called toxic debts only became so because the debtor lost their jobs as the real economy collapsed as the aggregate spending gap widened. If governments had ensured that gap did not widen then the scale of the debt crisis would have been significantly smaller. Many of what are now considered to be bad debts would have remained viable (good) debts had employment growth been maintained.

Llewellyn characterises the role of government in this way – and in doing so starts to ignore the elephant:

In response, governments have stepped in to fill that borrowing and spending “hole”. By so doing, they are indeed preventing demand from falling. But while it is currently easy for governments to borrow – to sell bonds – the resulting levels of debt will eventually start to worry investors. Then, as in the early 1980s, governments will have no option but to tighten fiscal policy. And that damages demand: 1982 saw zero growth among members of the OECD for the first time in its history.

The innocent reader would conclude that there is an essential borrowing-spending cycle that has to be maintained in a monetary system which has a symmetry about it. So if the private borrowing has lapsed and left a “spending hole” then government has to step in and take up the borrowing-spending function.

The reader will then conclude that this is not sustainable because the build-up of public debt “will eventually start to worry investors” and because governments have no other options austerity will have to be implemented which will damage demand and economic growth.

So the underlying message – government fiscal intervention cannot increase output in any permanent way and ultimately the private borrowing-spending cycle has to resume for there to be a sustained recovery.

And the innocent reader will have missed the whole family of very large elephants that Llewellyn conveniently forgets to mention. The reason he doesn’t mention them is because he is ideologically trapped in the defunct mainstream macroeconomics doctrine that neither predicted this crisis nor has the tools to solve it. He is probably one of the less trenchant members of that school but he still chooses to perpetuate the lies and misconceptions that are its hallmark.

First, unlike a household or a business firm, a sovereign government is never revenue constrained because it is the monopoly issuer of the currency. Sovereignty has a very particular meaning in Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and requires a national government issues its own currency and floats it on international markets. So Greece or Germany are not sovereign nations. We will come back to this point when we consider the latest Morgan Stanley report tomorrow.

A household or a business firm uses the currency issued by the government. It always has a financial constraint and must seek funds from saving, asset reduction, earnings or borrowing before it can spend a penny! Always!

The sovereign government issues the currency and, financially, can spend whatever it wants as long as there are real goods and services available for purchase in that currency. This is not the same thing as saying it should spend without care. The point is that it never has to “finance” such spending. It clearly only should spend to advance public purpose which would initially require it ensure all spending gaps are closed.

So there are limits on prudent government spending but they are never financial.

Second, if you appreciate that then you will immediately reject the proposed symmetry that Llewellyn implicitly sneaks into his analysis. There is no necessity for governments to borrow before they spend. They can always fill the “spending hole” without any borrowing if they so choose.

As I have explained before, sovereign government borrowing is a left-over from the convertible currency-gold standard days of fixed exchange rates. It has no real purpose in a fiat currency system with floating exchange rates although government debt can be used by the central bank in its liquidity management or reserve maintenance operations.

But as we know – a simpler way of ensuring control over the target interest rate and to stop interbank competition in the context of excess bank reserves – is for the central bank to pay a return on excess reserves.

But an even simpler solution is to leave the short-term nominal interest rate at zero and leave excess reserves in the system – the Japanese solution. Someone asked the other day – “what purpose does a zero interest rate serve?”. Why should the target interest rate serve any purpose other than to keep the risk-laden rates out on the maturity curve as low as possible? If inflation or asset bubbles continue to concern you then use direct methods available in fiscal policy to discipline those problems.

So why do governments issue bonds when they do not have to? I notice this question appears in the comments section regularly.

Let me repeat: a national government sovereign in its own currency is no longer revenue-constrained. It can spend however much it likes subject to there being real goods and services available for sale. Irrespective of whether the government has been spending more than revenue (taxation and bond sales) or less, on any particular day the government has the same capacity to spend as it did yesterday.

There is no such concept of the government being “out of money” or not being able to afford to fund a program. How much the national government spends is entirely of its own choosing. There are no financial restrictions on this capacity

So why do they borrow? There are several reasons – some technical and others ideological.

In a technical sense, when there are deficits bank reserves are growing and banks will try to get rid of these reserves by lending them on the overnight interbank market. The competition for funds drives the interest rate down to whatever support rate the central bank pays on overnight reserves. The problem is that the banks cannot eliminate the system-wide reserve surplus created by the deficits. If the system is left alone the central bank will lose control of its target interest rate.

As noted above there are two things the government can do to retain control over its monetary policy stance. It can offer an interest-bearing asset in place of the reserves – that is, sell the banks government bonds (that is, “borrow”) or it can pay the target interest rate on overnight reserves. The second option is currently being used in the US for example.

Further, governments borrow much more than is needed to fulfill the liquidity management function of the central bank. So then we have to understand the ideological nature of government borrow and its intrinsic lack of utility other than to provide corporate welfare to lazy bond investors.

The overwhelming sentiment of the business community and the conservative nature of our political system (and its participants) leads to a largely anti-government swell of opinion which is continually reinforced by the media – the “debt-deficit hysterics”. The neo-liberal expression of this over the last three decades has overwhelmingly imposed massive political restrictions on the ability of the government to use its fiscal policy powers under a fiat monetary system to ensure we have full employment.

We now accept very high unemployment and underemployment rates as a more or less permanent feature of our economic lives because of the political constraints imposed on government.

So while there was a major shift in history after the collapse of Bretton Woods, the logic that applied in the fixed exchange rate-convertibility days is still being imposed despite the economic fact that it does not apply in the fiat currency era.

As a result, governments imposes voluntary constraints on themselves for political reasons? The neo-liberal macroeconomic reasoning that you read about in the newspapers is really the sort of reasoning that prevailed in the days prior to fiat currency. The shift in history renders most of the textbook economics outdated and wrong, in terms of how they depict the operations of the fiat monetary system.

To see how this ideology works you just have to examine the establishment of the Australian Office of Financial Management (AOFM), which was set up as a special part of the Federal Treasury to management federal debt. The Australian experience is common around the world in almost all countries.

While there was a lot of hoopla about it being an “independent agency”, the reality is that this is all largely cosmetic – the AOFM is still part of the consolidated government.

Prior to this bond issues were made using the “tap system”. The government would announce some face value and coupon rate at which it would issue debt and “turn the tap on hard enough” to meet the demand at that yield. Occasionally, given other rates of return in the financial markets the issue would not be fully subscribed – meaning some of the net spending would be covered in an accounting sense by central bank buying treasury bills (government lending to itself!).

This system was highly criticised and in 2000 the Deputy Chief Executive Officer of AOFM (seemingly content on perpetuating neo-liberal myths) claimed it was:

… breaching what is today regarded as a central tenet of government financing – that the government fully fund itself in the market. It then became the central bank’s task to operate in the market to offset the obvious inflationary consequences of this form of financing, muddying the waters between monetary policy and debt management operations.

As to the so-called “central tenet” – this is pure ideology and has no foundation in economic theory. It is a political statement.

But the impact was to constrain the government from creating full employment, which the conservatives hated because it threatened to redistribute more of the national income toward labour. Since the 1980s as governments maintained high rates of labour underutilisation under pressure to do so from the business lobby, the profit share in national income has burgeoned.

Further, there is an automatic assumption drawn from neo-liberal doctrine that budget deficits are inflationary and have to be funded. The former statement is not necessarily true (it might be true under special circumstances that have not applied for a long time) and the latter statement about funding is untrue – categorically.

Anyway, the Federal government introduced some really stupid reforms to the way government bond markets operated. All these policy choices and changes to the “operations” of the bond markets were voluntary choices by the Government based on ideology. There is nothing essential about the changes. Further, they are largely cosmetic.

They replaced the tap system with an auction model to eliminate the alleged possibility of a “funding shortfall”. Accordingly, the system now ensures that that all net government spending is matched $-for-$ by borrowing from the private market. So net spending appeared to be “fully funded” (in the erroneous neo-liberal terminology) by the market.

But in fact, all that was happening was that the Government was coincidently draining the same amount from reserves as it was adding to the banks each day and swapping cash in reserves for government paper. The bond drain meant that competition in the interbank market to get rid of the excess reserves would not drive the interest rate down.

The auction model merely supplied the required volume of government paper at whatever price was bid in the market. So there was never any shortfall of bids because obviously the auction would drive the price (returns) up so that the desired holdings of bonds by the private sector increased accordingly.

As an aside, at that point the secondary bond market started to boom because institutions now saw they could create derivatives from these assets etc. The slippery slope was beginning to be built.

But you see the ideology behind the decision by examining the documentation of the day. This quote is from a speech from the Deputy Chief Executive Officer of AOFM. He is talking about the so-called captive arrangements, where financial institutions were required under prudential regulations to hold certain proportions of their reserves in the form of government bonds as a liquidity haven.

… the arrangements also ensured a continued demand from growing financial institutions for government securities and doubtless assisted the authorities to issue government bonds at lower interest rates than would otherwise have been the case … Because such arrangements provide governments with the scope to raise funds comparatively cheaply, an important fiscal discipline is removed and governments may be encouraged to be less careful in their spending decisions.

So you see the ideological slant. They wanted to change the system to voluntary limit what the Federal government could do in terms of fiscal policy. This was the period in which full employment was abandoned and the national government started to divest itself of its responsibilities to regulate and stimulate economic activity.

And in case you aren’t convinced, here is more from AOFM:

The reduced fiscal discipline associated with a government having a capacity to raise cheap funds from the central bank, the likely inflationary consequences of this form of ‘official sector’ funding … It is with good reason that it is now widely accepted that sound financial management requires that the two activities are kept separate.

Read it over: reduced fiscal discipline … that was the driving force. They were aiming to wind back the government and so they wanted to impose as many voluntary constraints on its operations as they could think off. All basically unnecessary (because there is no financing requirement), many largely cosmetic (the creation of the AOFM) and all easily able to be sold to us suckers by neo-liberal spin doctors as reflecting … read it again … “sound financial management”.

What this allowed was the relentless campaign by conservatives, still being fought, against the legitimate and responsible use of budget deficits. What this led to was the abandonment of full employment.

Third, the statement that “governments will have no option but to tighten fiscal policy” if bond markets get a bit edgy is patently ideological. A sovereign government never should tighten fiscal policy as long as aggregate demand is deficient – that is, is not sufficient to absorb all the real productive capacity including labour.

The composition of fiscal policy matters and a savvy government can tighten segments of spending while expanding other components leaving the overall level of aggregate demand unchanged or even growing.

It is clear that a sovereign government can do what it likes in relation to bonds and/or bond yields if it has the political will. It can decline to issue bonds or set their yields in concert with central bank operations. It is a total myth that a sovereign government is at the behest of the bond markets.

The reality is that the bond investors queue up daily to get their avaricious hands on as much debt as sovereign governments can offer. They sometimes get ahead of themselves and believe all the nonsense they read from the likes of Société Générale and Morgan Stanley and make big mistakes by taking short positions on government debt.

But overall they only call the tune if government lets them. Sadly, the neo-liberal era has seen governments repeatedly sacrifice the welfare of their citizens to satisfy the bond markets. Please read my blog – Who is in charge? – for more discussion on this point.

More evidence to support further fiscal stimulus

The June quarter National Accounts will be released for Australia next Wednesday (September 1, 2010) and the early indicators are now that growth is continuing to slow. Several economic indicators (including the negative full-time employment growth that the recent Labour Force data revealed) are now pointing in the same direction – slowdown as the fiscal stimulus wanes.

The latest evidence to support this comes in the form of today’s release by the Australian Bureau of Statistics of its Private New Capital Expenditure and Expected Expenditure data for the June quarter. This data obviously forms part of the subsequent National Accounts estimates for investment spending.

All the bank and business economists as is usual got it wrong. You have to wonder who actually relies on their advice for anything. They are so out of paradigm (MMT) that they fail almost every time to understand what is going on at the macroeconomic level.

This group of economists “were forecasting a rise in capital expenditure of 2.3 per cent” (Source).

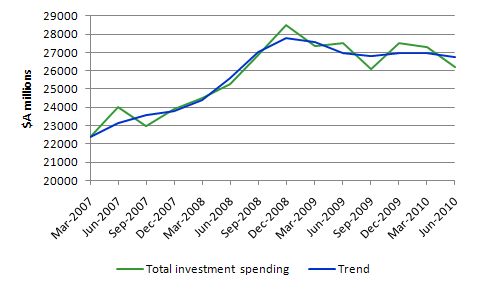

Instead, real capital expenditure has fallen by 4.8 per cent (seasonally adjusted) in the June quarter which is a significant drop. The following graph shows seasonally adjusted capital investment and its trend since March 2007. The trend is negative and has been since December 2008.

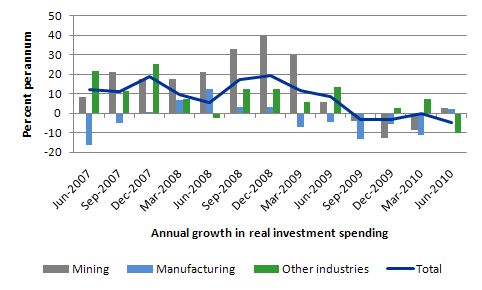

The next bar graph shows the annual growth of capital expenditure by industry (Mining, Manufacturing and Other) with the blue line showing the growth in total capital spending.

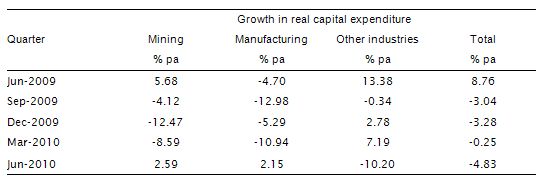

The following Table shows the annual growth in real capital expenditure for different industries over the last 4 quarters. Real capital spending has been declining consistently for the last year. Even the much touted investment boom in Mining is not evident in the data. All the talk that the Mining sector saved the economy from recession is total nonsense. Investment in that sector has been in decline for the last three quarters and showed modest improvement in the June quarter.

The major decline in other industries which includes all those which were most advantaged by the fiscal stimulus (retail, construction) are now in serious decline. You can see that while the stimulus was working through the expenditure system these industries generally resisted the trend that was occurring elsewhere in the economy.

The conservative side of politics is claiming that the proposed mining tax that the government (well it still sort of is the government pending the outcome of the hung parliament from last weekend’s national election) has caused mining investment to plummet.

The ABC news report quoted some bank economist who tried to give succour to the conservative view:

Given the overall outlook for mining you would’ve expected a much larger increase … It does seem that global uncertainty, plus the uncertainty over the resources tax here in Australia, and perhaps the raising of interest rates, has weighed on capital expenditure in the second quarter.

Sorry to say this commentator does care to comment on other aspects of the data.

The ABS data also publishes expected investment. For Mining they are expecting to increase their capital spending by 29 per cent on their actual 2009-10 capital expenditure and their expectations have been revised upwards for next year from what they were a year ago.

The bank economist doesn’t seem to realise that the actual June quarter investment spending was probably decided upon some quarters ago and the mining tax was only announced in May (that is within the June quarter). Why that commentator is given space in the national media is beyond me.

It is also true that overall, investment expectations are looking better than they were last year. This suggests that economic growth will remain positive over the next 4 quarters.

Conclusion

In tomorrow’s blog – the elephant gets bigger and its absence is even more laughable. We will explore attention deficit syndromes in the financial markets. Therapy is prescribed and I am researching appropriate psychology services so I have something constructive to offer :-).

That is enough for today!

Bill: you repeat the popular idea that given rising reserves at a central bank, the latter borrows in order to maintain an interest rate target. But what’s the point of this target?” For example, rising reserves implies an attempt at stimulus, and since falling interest rates are a form of stimulus, why not just let interest rates fall? Or more generally, why not let interest rates look after themselves?

Of course some fine tuning can be done via interest rates, but the latter is a crude tool: it influences an economy only via people and firms significantly reliant on variable rate loans. Adjusting demand by altering for example a payroll tax (as suggested by Warren Mosler) is far better because it affects every employer and employee in the country.

Re the historical reasons for unnecessary government borrowing, I think there is an additional strand here. Keynes, Friedman, and others were aware in the 1930s and 40s that “print and spend” was an alternative to “borrow and spend”. So why didn’t they advocate “print” (i.e. money creation) more forcefully? I think there is a clue in what Keynes said about Abba Lerner (an advocate of print and spend). Keynes said “Lerner’s argument is impeccable but heaven help anyone who tries to put it across to the plain man at this stage of the evolution of our ideas.” I.e. Keynes possibly regarded those around him as economic illiterates who understood the word “borrow”, but who would go apoplectic at the idea of deliberate money creation.

As an aside, I am wondering if you can give your interpretation of what mainstream economists refer to as the “real” rate of interest. Obviously, by identity, this is just the (presumably short term) nominal interest rate with inflation netted out.

There was a big to-do on a number of economics blogs over a piece by Minnesota Fed President Narayan Kocherlakota, who argued that the Fed’s QE is deflationary. His argument is that since, in the long run, the “real” interest rate will eventually rise to its historical level of 1-2%, a permanently low Fed Funds Rate must cause deflation. So, for example, if the FFR target is 1%, and the real interest rate is 2%, then we must have deflation of (roughly) 1% to satisfy the Fischer equation.

Many center-left economics bloggers were harshly critical of this proposition, but they ultimately employed the idea of a real interest rate in their critiques. One such blog posited a scenario where, if the Fed kept rates at zero while the real rate was positive, money would eventually become worthless as there would be no benefit to lending/no cost to borrowing.

To an extent, I can understand the critics of Kocherlakota’s argument. It is ridiculous to think that a low FFR would mean deflation, essentially via the identity of the Fischer equation. Clearly this equation is an ex-post identity and not a model of three independent variables. But his critics at the same time argue through use of the real interest rate that a permanently zero FFR would result in inflation. I don’t see how this must be the case either. Both imply that the Fed, and the Fed only, controls the rate of inflation (and interest) in the economy.

In any case, just wondering what your thoughts on the “real” rate of interest were, how to interpret it, and what its significance is.

Thanks.

“If governments had ensured that gap did not widen then the scale of the debt crisis would have been significantly smaller.”

Isn’t part of the cause of the spending gap an increase in debt? Debt causes a transfer of wealth from the poor to the rich, and since the rich have a lower marginal propensity to consume, the spending gap widens. If debt decreases then more money is in the hands of the poor who will spend more.

The largest debt one will ever have is usually a mortgage and in recent years the price of land has become a bubble. Since living somewhere is a necessity, the lack of management of the land bubble has caused a massive increase in debt (and is caused by debt.) If land rent and expectations of future rent could not be capitalized into a loan then debt will decrease, income inequality decreases, and the spending gap decreases! I’m not saying government intervention isn’t necessary, but I believe Henry George’s land value tax can go along way to decreasing the spending gap.

“So net public spending has to finance that saving or in his words “to ensure that the economy’s full rate of saving gets spent”.”

Banks don’t lend from the economy’s savings. The Basel accords require OECD banks to keep roughly 8% of deposits in reserve (“adequate capitalisation”.) The other 92% of depositors money doesn’t however stay out of use because it has been loaned: it continues to circulate as checkbook money for the payment of goods and services. (Everyone subconsciously knows this – they do not expect not to be able to withdraw money because it has been loaned.) This practice is called fractional reserve banking.

Furthermore, the multiplier effect ensures that money borrowed from one bank can serve as another bank’s reserve requirements once deposited with them. (The sellers of goods bought with borrowed money will deposit this money in their bank) This enables a further loan on up to 92% of the value of the initial deposit. And so on. The multiplier effect allows an original deposit of ‘Government money’ of $1000 to create $12,500 in additional ‘bank money.’

Read up on Fractional Reserve Banking here: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fractional_reserve_banking

I second ds’ request. Here is my response to the debate I left over at Mark Thoma’s blog:

http://economistsview.typepad.com/economistsview/2010/08/jaws-are-hardening.html#comment-6a00d83451b33869e20134867b0121970c

Ralph,

I think the problem the plain man has with “print and spend” or “deliberate money creation” goes all the way back to the US civil war. It’s been awhile since I studied it, but the US issued the greenback as fiat money on par with the gold money. The greenback lost value against the gold dollar. I think the idea that printed money will lose value still exist because of the greenback. It’s a belief everyone has even though they do not know the origin of the belief. I also seem to recall the govt agreed to sell bonds in exchange for greenbacks but had to pay interest to the bondholders in gold (not greenbacks). I guess the bond traders were in charge in those days too!

I’d be interested in a brief history of tap vs auction system for pricing federal debt in the U.S. Any good links? It’s my understanding that we had something like a tap system during WW II … is that correct?

Ken

NKlein1553, I suggest checking out Ka-Poom theory from iTulip.com.

http://www.itulip.com/forums/showthread.php/428-Ka-Poom-Theory-is-a-Rhyme-not-a-Repeat-of-History

Ken,

I would suggest you read K. Garbade at the NYFed. He’s their top guy on the history of Treasuries. Can’t recall exactly if he’s written on that specific issue, but if he has, it will be on the NYFed’s site.

Bill Said:It is also true that overall, investment expectations are looking better than they were last year. This suggests that economic growth will remain positive over the next 4 quarters

I was doing OK until I read this one. If the next 4 quarters are possitive is it just the predicted increase in mining investment that pulls it up? Retail is realy struggling at the moment. I have deep contact into retail rent collection by retail property managers in Brisbane and arrears are climbing fast. Not as bad at the early 1990s but headed in that direction. Anyone know?

Thanks for the posts Bill. This one is written in a way that is easy to understand. That is appreciated.

Ken,

Articles for you :

Auction: http://www.ny.frb.org/research/current_issues/ci11-2.html

Yield curve during WWII: http://www.richmondfed.org/publications/research/economic_quarterly/2001/winter/pdf/hetzel.pdf

Scott, Ramanan … thanks for the suggestions … I’ll check them out.

Ken

NKlein1553, I believe Brad DeLong gets one right here.

http://delong.typepad.com/sdj/2010/08/narayana-kocherlakota-confuses-must-lead-with-is-the-result-of.html

“Admittedly, this is a hard thing to do–the kind of thing that requires a highly trained incapacity–but Narayana has managed to do it when he writes:

over the long run, a low fed funds rate must lead to consistent-but low-levels of deflation…

The claim is completely correct–but only when you replace “must lead to” with “is the result of.””

markg: “I think the problem the plain man has with “print and spend” or “deliberate money creation” goes all the way back to the US civil war. It’s been awhile since I studied it, but the US issued the greenback as fiat money on par with the gold money. The greenback lost value against the gold dollar. I think the idea that printed money will lose value still exist because of the greenback. It’s a belief everyone has even though they do not know the origin of the belief. I also seem to recall the govt agreed to sell bonds in exchange for greenbacks but had to pay interest to the bondholders in gold (not greenbacks). I guess the bond traders were in charge in those days too!”

Check the history of greenbacks again. First, if the bond traders had been in charge, there would not have been any greenbacks. Lincoln asked Congress to issue greenbacks because the interest being asked to finance the war by borrowing was too high. (The war was not completely financed by greenbacks, however.) Second, the loss of value of the greenback was temporary, IIRC. After the war it returned to parity with other dollars, where it remained until the last greenback was retired, well into the 20th century.

As to the “plain man’s problem” with “print and spend”, are you sure that there is one? (Not that some people don’t have a problem with it.) I have never gotten an argument, online or off, when I say that the gov’t is the source of money, even from those who have been arguing that the gov’t needs to borrow. I have never had anybody dispute that fact. It seems to be one of those things that “everybody knows”. That fact obviously implies the power to “print and spend”. Ask the plain man whether it is better to borrow and spend or to print and spend (and therefore pay no interest). How many will be in favor of paying interest?

Min,

From Wikipedia, the greenback was below par from 1862 to 1879. I guess 17 years could be considered temporary. As for the bond traders and general public Wiki says: “The limitations to the legal tender status were quite controversial. Thaddeus Stevens, the Chairman of the House of Representatives Committee of Ways and Means, which had authored an earlier version of the Legal Tender Act that would have made United States Notes a legal tender for all debts, denounced the exceptions, calling the new bill “mischievous” because it made United States Notes an intentionally depreciated currency for the masses, while the banks who loaned to the government got “sound money” in gold. This controversy would continue until the removal of the exceptions in 1933.”

The denounced exceptions were “they could not be used by merchants to pay customs duties on imports and could not be used by the government to pay interest on its bonds. The Act did provide that the notes be receivable by the government for short term deposits at 5% interest, and for the purchase of 6% interest 20-year bonds at par. The rationale for these terms was that the Union government would preserve its credit-worthiness by supporting the value of its bonds by paying their interest in gold”.

So I think those “mischievous” feelings still exist towards issueing fiat money to fund spending. It’s completely misguided, but I hear it all the time in the media – “the Fed is printing money at record rates and ….”.

Bill said: “If inflation or asset bubbles continue to concern you then use direct methods available in fiscal policy to discipline those problems.”

Some of the arguments against MMT in respect to the financial crisis relate to the assumption that creating more money will just give the private sector the funds to continue their debt binge, ultimately making it worse. Is there a prescribed framework within MMT for dealing with, for instance, inflated house prices due to debt-fuelled speculation?