It's Wednesday, and as usual I scout around various issues that I have been thinking…

Who is going to pay?

I am working on a book at present on the way recessions entrench growing disadvantage beyond the costs that the actual crisis period imposes on the unemployed and others. The idea is that the neo-liberal era has systematically been associated with a trend towards erosion of working conditions and a rising inequality in outcomes far beyond anything that could remotely be justified by disparate individual or sectoral productivity trends. It is clear that the rise of the financial sector has been generated a massive redistribution of national income in most countries away from workers and productive sectors. As part of this research I am delving beyond the usual “economic” analysis that I might take of recessions. I am also trying to document how recessions occur and how the recessions of the last 40 years have reflected a growing disregard by our governments for their legitimate responsibilities to advance public purpose. In turn, this disregard has seen them turn a blind eye to corruption and incompetence in the private sector while we were being told that by privatisation and deregulation they had solved the macroeconomic problem and we would enjoy unparalleled prosperity. It was a con job of major proportions and now the question should be who is going to pay for all the damage they caused?

Trichet in denial

I also read the recent speech – Lessons from the crisis – that out-going ECB boss Jean-Claude Trichet gave to the European American Press Club, in Paris on December 3, 2010.

Apropos of the title – it is clear that the speaker and most of his cohort have learned zip from the crisis.

He claimed that the ECB had succeeded in its “price stability” charter but fails to mention that this has come about via depressed demand in most member states which held unemployment rates at persistently high levels.

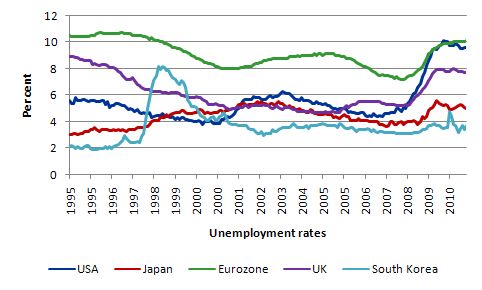

The following graph is enough to tell me that the Eurozone did not generate good outcomes even prior to the crisis. The data is taken from the RBA International Statistics and shows unemployment rates for the US, Japan, Eurozone, UK and South Korea.

Even the struggling Japan managed to keep it national unemployment rate down. But the Eurozone stands out. Over its lifetime it has consistently failed to generate enough work for its labour force.

Trichet blames poor fiscal policy for the crisis – “The roots of the sovereign debt tensions we face today lie in the neglect of the rules for fiscal discipline that the founding fathers of Economic and Monetary Union laid out in the Maastricht Treaty” – but fails to explain how, for example, Spain is in so much trouble given it was an exemplar of good “Maastricht behaviour”.

He also implicates “policy slippage” in “macroeconomic policies” by which he means some governments allowed workers to enjoy modest real wage growth which “entail significant losses over time in competitiveness”. There is clearly disparities in relative productivity and unit labour costs across the Eurozone. That did not contribute to the crisis.

The crisis was not caused by a wage explosion. On the contrary, the rising inequality across the Eurozone in terms of shares of national income are in favour of the profits share.

The crisis was caused by a major negative aggregate demand shock which exposed the basic design flaws of the monetary union. These design flaws were magnified by the outrageous behaviour of the financial sector – in particular, the banking sector which is now teetering on the brink of collapse – and being propped up by government handouts.

Any relative disparities in real wages and productivity growth were minor compared to what the banks were up to during the decade prior to the crisis. There was a major policy failure to be sure. But it wasn’t in the fiscal arena. Rather, it was the capture of governments by the neo-liberals and the resulting regulative laxity that allowed the crisis to occur.

And as usual – a poor diagnosis leads to a poor remedy. By erroneously implicating fiscal policy and macroeconomic policy in general as the cause of the crisis these characters can easily convince us that fiscal austerity and harsh cuts in pay and conditions are the way forward. They recruit the mainstream members of my profession to tell us that this will free up space for a strong private spending recovery.

It is patent nonsense. Ireland began its cruel austerity push nearly 2 years ago. They were meant to be enjoying prosperity by now. Instead, as was obvious to anyone but the denial cohort, their plight is worsening and they are being propped up by handouts from foreign governments.

The problem is the handouts demand more austerity. Ireland is on a downward spiral to a very bad place. But the bankers are still receiving their bonuses and/or have retired on huge pensions. The same thing can be said for Greece. The data now coming out as the austerity programs begin to bite indicates they are following the Irish to oblivion.

But while the EU leaders step back from taking any blame and extol the virtues of fiscal austerity the indicators they tell us matter (the public financial ratios – public debt to GDP ratio, budget deficit to GDP ratio) go in the opposite direction to what they want.

This is entirely predictable. Spending equals income. Growth in spending drive income growth. Income growth drives tax revenue and reduces welfare payments. These automatic stabilisers, in turn, reduce the budget deficits.

You cannot reduce the budget deficit with austerity unless exogenous spending growth happens to occur. That is, the external sector fills the gap left by the fiscal withdrawal and the private spending collapse.

The overwhelming emphasis – consistent with the IMF mantra of export led growth – is that nations can only improve their situations now via trade. This delusion lies behind Trichet’s remarks about relative competitiveness.

But with fiscal austerity being imposed generally and world export markets languishing it is foolish to think that the southern EMU nations will find export markets of sufficient size to fill the spending gaps left by the domestic spending withdrawal.

Please read my blogs – Fiscal austerity – the newest fallacy of composition and Export-led growth strategies will fail – for more discussion on why this strategy will fail in current circumstances.

The point is that the political leaders (Trichet is effective a political leader given how ideological and politicised the ECB is) continue to divert attention away from the underlying causes of the crisis. They clearly have an incentive to do this because they were complicit in the crisis – they turned a blind eye to criminal and/or incompetent behaviour from the financial markets and other corporate types.

But there is growing hostility to this failure to bring anyone to account.

So who is going to pay?

In this context I thought Will Hutton’s latest book is interesting. Over the weekend I heard Hutton interviewed on the local ABC radio program – Saturday Extra – where he was discussing his recent book Them and Us.

In that book (which I recommend notwithstanding its serious limitations and poor editing) Hutton says:

Britain today is more polarised than 10 years ago: the economic bubble has created both a new super-rich and a disenfranchised underclass. We need to return to our core moral values and find a new way of making a living, argues Will Hutton in this extract from his new book. Let’s start, he says, with fairness…

The British are a lost tribe – disoriented, brooding and suspicious. They have lived through the biggest bank bail-out in history and the deepest recession since the 1930s, and they are now being warned that they face a decade of unparalleled public and private austerity. Yet only a few years earlier their political and business leaders were congratulating themselves on creating a new economic alchemy of unbroken growth based on financial services, open markets and a seemingly unending credit and property boom. As we know now, that was a false prospectus … Yet while the country is now exhorted to tighten its belt and pay off its debts, those who created the crisis – the country’s CEOs and bankers, still living on Planet Extravagance, not to mention mainstream politicians – all want to get back to “business as usual”: the world of 1997 to 2007.

Hutton notes that “most of the working population do not deserve the degree of austerity and lost opportunity that lies ahead of them” – that they did not cause this wreckage and “those who did cause the crisis have got away largely scot-free”.

I was talking about this over the weekend with my co-author Randy Wray (we were also laying plans to finalise our Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) textbook which should be out in 2011 – perhaps in some form by mid-year. We were considering the bank foreclosure scandals in the US which I touched upon in my blog yesterday – The public sector and free information are essential for collective well-being

What is to be done to the fraudsters, the cheats, the liars – all those wealthy bankers and CEOS – who systematically stole real GDP from the workers through a series of ruses (many illegal) while their mates in government turned a blind eye?

Hutton’s book also considers this question. He is especially appalled that after the neo-liberals caused the crisis they are now once again gaining ascendancy in the media and explicitly via the political process (for example, the Tory victory in Britain and the mid-term election calamity in the US) and this conservative putsch:

… [in] … its repudiation of Keynesian economic policies in circumstances that demand more Keynesianism than at any time since the 1930s threatens to overwhelm its best intentions. The consequences are a potential national calamity.

In the period leading up to the crisis they had convinced us that Keynesian economics was dead. I cover the success of this smokescreen in this blog – The Great Moderation myth – which coincided with a succession of mainstream economists declaring the “business cycle is dead”.

These (arrogant) preponderances are Hutton’s “false prospectuses”. None of the mainstream economists who associated themselves with this myth – and all of them did – should be listened to again. They should be sacked for lying to their students and writing false Op Ed pieces in the wider media.

But now they are creeping out of their rat-holes and once again throwing their weight around. I can assure you there is no intellectual weight being brought to bear – it is all hot air and smokescreens. If there is any weight being thrown around it would be the result of too many long lunches in university clubs convincing each other that they had something to offer.

The damage is growing though as these characters convince governments to throw petrol (fiscal austerity) on the fire (the collapse that mainstream economists helped to cause).

Hutton documents the rising inequality during the pre-crisis growth period in detail and that narrative alone is worth reading. But his forward-looking agenda is to seek a “shared understanding of what constitutes fairness in order to restore our society”.

He says there is no such understanding:

The rich argue that it is fair for them to be so wealthy, in much the same way as Athenian noblemen believed that their riches were signifiers of their worth. They believe they owe little or nothing to society, government or public institutions. They accept no limit or proportionality to their wealth, benchmarking themselves only against their fellow rich. Philanthropic giving is declining; tax avoidance is rising; and executive pay is rising exponentially. All three are justified by the doctrine that the rich simply deserve to be rich. Meanwhile, the poor, in their view – and that of a virulent right-wing media – largely deserve their plight because they could have chosen otherwise. The mockery of chavs is premised on the assumption that they could be different if they wanted to be. The poor could work, save and show some initiative. So why should we indulge them by giving them state handouts?

This is a statement of the neo-liberal agenda par excellence. This approach is embodied in the OECD Jobs Study (1994) agenda which sought to “blame the victim” (the unemployed) for what was a systemic crisis beyond their control. A single unemployed worker have virtually zero capacity to improve their circumstances when aggregate demand deficiencies ration the number of jobs available in the economy.

The recent crisis has taken this nonsense to a higher level. We now have criminals who by their own greed and incompetence have destroyed the savings of millions and rendered the future prosperity of millions fraught (via pension cuts etc) standing tall and receiving trillions in government handouts. Only a few of them have faced any legal penalties.

Hutton says that this is demonstrated by the “arrogance with which bankers still defend their bonuses, in spite of everything that has happened over the past few years”. They invoke the defence that their remuneration are “private contracts” and that the “state has no right to interfere” yet have their greedy hands out as far as they can reach to get the public bailout funds which saved their jobs in the first place.

Hutton’s message is solidified in his proposal that the paradigm built on the “blind faith in individualism and markets” which has delivered grotesque inequalities and, finally, the worst crisis for 80 years must be exposed. He concludes that:

… is why we now need a Truth and Reconciliation Commission for British capitalism – to examine what happened over the last 10 years, apportion blame, demand atonement and use the lessons learned to build something better in the future.

I have no truck for Hutton’s conclusions that “the growth of public debt must be capped and Britain’s budget deficit reduced” and his understanding of the way the monetary system operates is poor (and inaccurate). But that doesn’t stop me from agreeing with him that somehow society will only start to see this historical period in true relief if the criminals are brought to justice.

Conclusion

We are setting up the conditions for the next crisis by denying the causes of the current one. The arrogance of the likes of Trichet and his cohort is contributing to this mass denial. Apparently, they were performing well and evil governments were being profligate. The solution is to rein in these governments and reduce real wages and make workers work harder – even though employment growth is stagnant or going backwards.

Apparently, austerity is the new bounty! This denial will further damage our economies and the longer the world wallows in low growth (or backward slides in to recession) the worse the losses will be for those denied access to work and the distribution system.

Saving balances are vanishing. Pensions are being cut and major US states will almost certainly default of their present pension obligations. Workers are losing their homes as a result of illegal foreclosures. If we step back one step we realise that unemployment renders a “good debt” a “toxic debt”. I am not denying that some of the credit was toxic (that is, had no hope of being repaid). That sort of debt was part of the “pass the parcel” that the crooks were engaged in as each successive step in the securitisation sequence delivered commissions and other income to the players while the risks mounted.

But overall the private debt and housing crisis is being grossly exacerbated by the unemployment. National (sovereign) governments could solve that immediately through public job creation. But they are part of the denial game that Trichet and his cohort engage in and perpetuate.

There really is a need to bring these characters – at every level of the decision-making chain – to account. Government officials including Presidents, Prime Ministers etc down to bank officials who took instructions should be brought in front of national commissions to justify and defend charges of incompetence and crimes against humanity. Prison terms would certainly be appropriate for thousands of these characters.

That is enough for today!

Indeed! I am looking forward to the time when these toxic vermin are brought to heel. I am happy to contribute to that process.

Here in Italy it seems to me that there are 2 options available (excluding Trichet’s one…):

a restructuring of our public debt via default or more public deficits as i understand MMT would suggest

What do you think is the best option for workers? I’m trying to think abt the + and the – of the two options from a workers’ point of view. Thanks

1. Maastricht criteria are just a guideline, but you always have to use your head as a country.

It is about being able to pay back the money you borrowed.

Spain has a relatively low sov. debt, but eg:

-huge potential exposure in the bankingsector, which might end up with the state and certainly influences its economic fundamentals.

-bad fundamentals, high labor costs, few opportunities for growth.

The rule is simply: ‘keep on the safe side of the fence’. To do so you not only have to take into account your current debt, but also potentials like costs of crisis; stimilus money; extra expenditure on welfare for unemployed; lower growth (read repayment possibilities). Everything added up brought Spain to the wrong side of the fence. Basically they are not there yet, but it is very likely that they will get there if everything becomes clear. Plus they are slow in making the exposures clear.

The safe side of the fence is not the same for all countries, Germany can afford more (because of its size; potential; well functioning government and tax collection and good reputation) than Spain.

So basically what Spain should have done is calculate how far they could go (eg by using Germany minus a realistic deduction as a max percentage) taking into account a market in a crisis.

Deduct all realisticly possible exposures and possible funds required in a crisis and not go over that amount preferably keep at least 5-10% away from it.

It simply did not do so.

2. Like everybody else Trichet want to solve the crisis, but it looks like he clearly donot want to solve them in a way that leaves a huge potential for future crisis.

A future crisis will probably kill the Euro project.

The main PIIGS problems is not simply : too much debt. It is that plus eg an inefficient unrealiable government and being uncompetitive.

These countries have a history of not keeping agreements and corruption (allthough especially Spain has made progress in this respect).

The Northern countries cannot afford to solve the crisis with the PIIGS and provide them with stimulus money. economicly maybe just, but it would be political suicide.

Imho Trichet understands that when he wants to safe the Euro not only this problem (where everybody is focussing on) should be solved, but also a repeat should be excluded. Which means bringing the fiscal house in order and restore competitiveness and history shows most PIIGS only move when they are forced. So as they not move otherwise they are forced. In other words it looks like he is in a balancing act between solving this crisis and avoiding future ones.

Interesting question, I’d like to share my 10 cents, if that’s ok.

In the short term, more public deficit and politically agreed fiscal transfer would in theory be more beneficial to workers (it would at least preserve the status quo). But the Euro zone is not allowing enough fiscal transfer to improve the economic situation and hence punishing the workforce.

In the case of a default, the powers would choose which bond holders take a hair cut. Being a cynical person I would say they would choose the little people to take the fall. If any country defaulted the heightened risk could collapse the entire banking system requiring the ECB to issue a lot of Euros to bailout the banks. Workers might get trampled in the chaos as some businesses go bust.

In the long term, as Bill says the defaulting Nations would be wholly sovereign and could chart their own course. Favourable to workers if they choose that path.

But in the end, for all the talk of “major negative aggregate demand shock”, there is a debt and somebody must pay.

Who must pay? Well, who spent the money?

Getting Will Hutton on side would be a major win, but at the moment he is still living in the UK socialist nirvana that is European integration and the ‘stability’ that apparently would offer us.

For some reason UK Labour and left wing supporters are terrified of floating exchange rates. I suspect this is a throw back to completely messing up in the mid 70s.

All the champagne socialist set have too much invested in the European dream and find it difficult to let go. From my pragmatic system design point of view we need an unlikely Chimera of the UK independence party (getting us out of Europe and focussed on the domestic economy) and the left of the Labour party (sorting out unemployment by public spending).

Neil,

I think the British Labour Party has proved itself to be sufficiently pragmatic in its policies on Europe. My guess is that that will continue – there has been some recantation of earlier support for the euro (eg John Denham).

Getting Will Hutton on side would be a major win

I can’t really agree with that as Hutton is precisely the vapid pseudo-thinker that any opposition could well do without.

He may rather vaguely talk it, but he certainly does not walk it.

His stewardship of the industrial society was examined in private eye recently, its not online so here is a precis

ad 2000:

300 employees

20 million p/a income from training

90 odd years of performing as an independent useful organisation.

ad 2010:

43 employees

27 million pension fund deficit

Wound up in court and the husk absorbed into Lancaster University.

In between:

training functions flogged off to capita ( a service company that typifies the siphon economy)for £23 million

Renamed as ‘the work foundation’

Transformed into one more ‘think tank’ the world didn’t need

Currently:

Advertising for ‘exceptional interns’ ie unpaid workers.

Good Will Hutton chairs comittee on how to minimse income inequality, remit restricted to the Public Sector alone.

It might seem unfair to suggest his organisational acumen has any bearing on the worth of his ideas. However as who has struggled through the heroically turgid ‘The State we are in’, they do not seem to go beyond the notion that the rich should be nicer to the poor.

Many thanks for producing such an informative weblog.

Yeah, but like Polly Toynbee he’s a perennial talking head and those are important politically.

Yeah, but like Polly Toynbee he’s a perennial talking head and those are important politically.

They might be useful politically, but they are certainly not important. Hutton was in tight at the start of the new labour government but I fail to see what influence he had.

The fact that he is a go to guy if you want someone to warm a television studio chair ‘from the economic left’ is part of the problem.

I’ve been listening,with decreasing good will, to his well meaning guff for years. Watching him effortlessly glide into collaboration with the unscrupulous asset strippers that govern us makes me quite dyspeptic.

He observes, quite rightly, that income and inequality is a problem, but allows himself to be restricted to the public sector, where it is certainly less of a problem than in the private sphere.

How restructuring public sector pay, where at least the recipients pay normal tax rates, will mend the ways of the commanding heights of the private sector is quite beyond me.