This is the second part of my thoughts on the current acceleration in military spending…

The dead cat bounce – Latvian style

It is a holiday week in Australia – the cricket is on (not interested); the weather is good and it is virtually impossible to get a tradesperson to fix a new electricity connection. But who am I to complain when our fortunes are compared to the costs being endured in other nations where governments have deliberately followed policy trajectories which are designed to inflict damage on their real economies – in the mistaken belief that TINA rules. TINA (There Is No Alternative) is one of those neo-liberal ploys which hoodwinks citizens into believing that gross damage is better than really gross damage but which is really an agenda for retrenching the welfare state and freeing markets up for further private sector rape. There are alternatives to what is going on at present and it requires much stronger public sector intervention. I was thinking about this today when I was reviewing the latest data from Latvia which is now being held out as the “model” for the rest of Europe to follow. It is clear that eventually growth does return to these ravaged economies but that doesn’t validate the policy approach. It just says that business cycles cycle. The real way of assessing the alternatives is to compare how deep the policy-induced damage becomes and how long it lasts. The neo-liberal austerity line does not look good in that regard.

Conservatives have a way of revising history to suit their blighted view of the world. They seize on anything that they can construct as being supportive of their position and usually misrepresent the facts by omitting key factors which if widely known would otherwise indicate that the imputed causality is absent.

One of the growing examples of this is the way they are interpreting what is happening in the Baltic at present. Here we have an economically devastated region in the grip of a program of deliberately imposed fiscal austerity being held out as the exemplar for the rest of the world to follow.

It is the neo-liberal dream situation – a ravaged public sector which is contracting fast; public pensions being cut back severely; very high unemployment which ensures the workers will accept nominal pay cuts of whatever level the bosses think; no major new regulations on financial markets or capital in general – a wealth takeover by the elite aided and abetted by their cronies in government with no pesky trade unions to get in the way.

A neo-liberal nirvana.

The Economist Magazine started pushing the Latvian bandwagon in their October 7, 2010 article – Latvians defy conventional wisdom by re-electing an austerity government. The article gives the impression that the IMF “internal devaluation” route has been successful.

The article said that:

LATVIA’S recent history has seen off several axioms of modern political economy. One is that maintaining a fixed exchange rate in the midst of a slump is suicidal. Latvia kept its currency peg to the euro and has regained competitiveness through an “internal devaluation”, with large cuts in wages and public spending: a fiscal adjustment equivalent to some 14% of GDP.

Another axiom is that voters punish governments that impose tough austerity programmes. But the coalition headed by Valdis Dombrovskis, the prime minister, won the parliamentary election on October 2nd with 58.6% of the vote, despite presiding over a record 18% drop in GDP in 2009. Mr Dombrovskis’s Unity party almost doubled its seats in parliament, to 33 (out of 100).

So the link being made is clear – the impression is that the voters endorsed the fiscal austerity and with real GDP growing again, the IMF-style internal devalulation has been successful.

It used to be that the neo-liberals encouraged all nations to follow the Irish example – the Celtic Tiger. Please read my blogs – Live coverage now on and The Celtic Tiger is not a good example – for more discussion on this point.

Now, they are telling everyone that we should be looking to the Baltic. This Wall Street Journal article (December 10, 2010)- Irish Should Look to Baltics, Not Iceland – is another typical conservative revision.

I wrote about Latvia in this blog – When a country is wrecked by neo-liberalism – and the facts I present there are good background.

Fortunately, there is astute political scrutiny and you will learn something quite different by reading this UK Guardian article (December 20, 2010) – Latvia provides no magic solution for indebted economies.

The UK Guardian article challenges the view that the recent election outcome was a referendum about the fiscal austerity and thus determined by economic factors. They ask:

Was this proof that austerity measures could not only work, but actually be popular? Was Latvia the model that Greece, Ireland and Spain should emulate?

The UK Guardian article separates the political developments from the economic interpretation that the Economist article wants us to believe. In fact, there appears to be no case to be made that the recent election results were a referendum on the fiscal austerity measures.

It also helps that Latvia has no organised labour movement which is capable of mobilising worker dissent. In other words, the workers have to take what they get. The point made is that Latvia without coherent unions is not a model for nations where unions are stronger and can mobilise dissatisfaction and destabilise the political regime.

I won’t comment further on the political issues involved because I am not particularly qualified to provide any insights in that regard.

The reference to Iceland in the WSJ article is that since the crisis, the Icelandic currency (Krona) has falling by more than 30 per cent and this has stimulated exports (fishing and tourism) and real GDP is now growing. The decision by the central bank to cut interest rates has also been implicated in the emerging recovery.

The complication has been that around 15 per cent of debt held by households and firms was denominated in foreign currencies (courtesy of their incompetent banking sector) and so the burden of those loans has increased.

But the article rightly notes that Ireland cannot depreciate nor cut interest rates given its membership of the Eurozone. In that context, they argue that Ireland’s model should be the pegged-currency nations of the Baltic

In this context, the WSJ article claimed that:

Both Latvia and Estonia have voluntarily pegged their currencies to the euro with a view to entering the euro-zone as soon as possible. Estonia is set join at the start of 2011 and Latvia in 2014. Estonia’s peg dates back to 2004 … At the onset of the crisis, the two Baltic states faced a stark choice between the Icelandic model of devaluation … and listening to the voices from Frankfurt telling them not to give up their euro dreams and the stability and credibility the single currency could bring.

The reference to “stability and credibility the single currency could bring” is one of those “as long as we keep saying it people will believe it”. The single currency Eurozone is now highly unstable and lacking in credibility. You just have to ask the bond traders who the free market lobby consider to be the exemplars of wise counsel. They have concluded that the EMU is dysfunctional.

But WSJ acknowledges that the results of the fiscal austerity and wage deflation in Latvia have been “shocking”:

Latvia’s economy shrank a cumulative 25% in 2008 and 2009 … the most of any country during the crisis.

However, they argue that the claim that depreciation represents a “short sharp shock” against the “slow burn” of fiscal austerity combined with internal devaluation is incorrect. They suggest that “austerity can also be a fairly intense but short-lived agony”.

This reminds me of the old Monetarist claim that the best way to deflate was to push interest rates up and to use unemployment as a weapon to discipline wage demands which was a principle recommendation of the likes of Milton Friedman. The textbook presentation of this strategy never attach any time limits to the process.

At one point (I haven’t the reference at hand) Milton Friedman was asked how long the deflation (around the early 1980s) would have to take before the unemployment rate fell back to the NAIRU, which was held out as the “equilibrium” unemployment rate. Please read my blog – The dreaded NAIRU is still about! – for more discussion about the flaws in the NAIRU concept.

Friedman replied that it might take 15 years before the economy successfully deflated. In other words, he was advocated a deliberate policy-induced attack on jobs (maintaining high unemployment) for 15 years as a credible strategy.

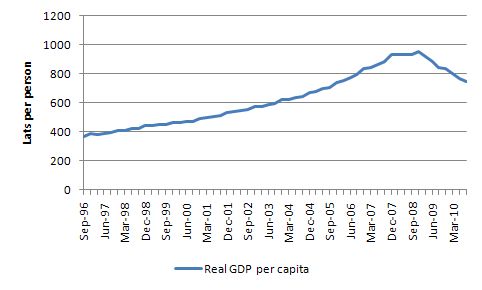

Latvian real GDP peaked in December 2007 and then plunged by around 25 per cent in the next two years. In the third-quarter 2010, real GDP in Latvia grew at an annualised rate of 2.9 per cent. Assuming that the economy grew at 3 per cent into the future, it would take until the second-quarter 2019 to restore the level of real GDP to the peak before the crisis in December 2007.

That is not a “short-lived agony”.

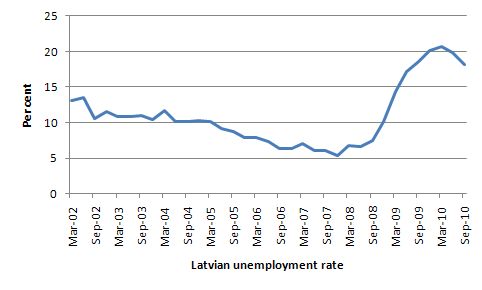

The following graph is taken from the official data available from Latvijas Statistika and shows that the official unemployment rate is still around 19 per cent

At current rate of labour force growth (which is highly subdued and will improve if persists) and labour productivity growth (which will also improve should growth persist), then it would take 25 quarters of uninterrupted real GDP growth to get the unemployment rate down to its December 2007 low-point (of 5.4 per cent).

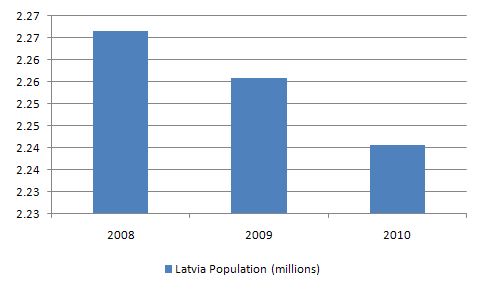

One of the striking adjustments that has accompanied the economic collapse and subsequent fiscal austerity has been the significant fall in the population as workers have migrated to find work elsewhere.

The following graph is taken from the official data available from Latvijas Statistika and shows that the population has shrunk since 2008 by around 1.2 per cent.

So clearly this sort of adjustment is not available as a general solution (people have to go somewhere).

Given the birth rate is falling (with data provided by Latvijas Statistika) one can work out the net out-migration component of the population decline.

In 2009, the population fell by 10,742 of which 10,057 was due to out-migration. The out-migration expanded in the first 11 months of 2010, with the population falling by 15,283 of which 14,409 was due to out-migration.

If you added these workers into the labour force (and assumed they would have been unemployed), then the unemployment rate would rise by more than 1 per cent.

The UK Guardian says that:

While the economic crisis was deep enough to drive even Latvia’s depoliticised population into the streets in the winter of 2009, most Latvians soon found the path of least resistance to be simply to emigrate. Neoliberal austerity has created demographic losses exceeding Stalin’s deportations back in the 1940s (although without the latter’s loss of life). As government cutbacks in education, healthcare and other basic social infrastructure threaten to undercut long-term development, young people are emigrating to better their lives rather than suffer in an economy without jobs. More than 12% of the overall population (and a much larger percentage of its labour force) now works abroad.

Children (what few of them there are as marriage and birth rates drop) have been left orphaned behind, prompting demographers to wonder how this small country can survive. So unless other debt-strapped European economies with populations far exceeding Latvia’s 2.3 million people can find foreign labour markets to accept their workers unemployed under the new financial austerity, this exit option will not be available.

With real GDP falling by some 30 per cent between 2008 and 2010 real GDP per capita has also fallen sharply even with the decline in population. On average, Latvians have lost 5 years of per capita income growth although the distributional inequalities will mean that the poorest will be significantly worse off than that.

This is not a short-lived agony.

While domestic demand has improved a little in Latvia in recent quarters (it was hard to see it going any lower) the outlook for business is still deteriorating.

The Business Tendency Key Indicators do not suggest that things are improving. You can read the details of how these indexes are constructed if you are interested.

The damage is spanning a generation and new entrants into the labour market will struggle to get the requisite skills development and experience and so entrench the disadvantage over time.

The UK Guardian says:

Is this “dead cat” bounce sufficiently compelling for other EU states to follow it over the fiscal cliff?

The Guardian notes that the Latvians are reprising the “old IMF austerity doctrine that failed in the developing world”. In terms of the IMF “internal devaluation” approach I remind readers of the following facts.

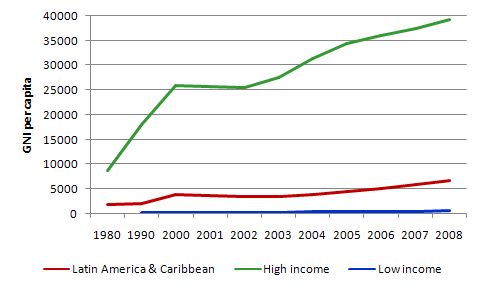

I produced this chart in this blog – IMF agreements pro-cyclical in low income countries – in October 2009. It uses data from the World Development Indicators, provided by the World Bank. It shows Gross National Income per capita, which, in material terms is an indicator of increasing welfare.

The overwhelming evidence is that these programs increase poverty and hardship rather than the other way around. Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa (which dominates the low income countries) were the regions that bore the brunt of the IMF structural adjustment programs (SAPs) since the 1980s.

The SAPs relied in part on internal devaluation combined with fiscal austerity as the way to make the export sector competitive.

While the high income countries enjoyed strong per capita income growth over the period shown (since 1980), Latin America (and the Caribbean) has experienced modest growth and the low income countries actually became poorer between 1980 and 2006.

The two trends are not unrelated. The SAPs were responsible for transferring income from resource wealth from low income to high income countries.

Please read my blog – Export-led growth strategies will fail – for more discussion on this point.

The other issue not dealt with in the pro-internal devaluation approach is that it provides domestic residents with less flexibility in re-arranging their expenditure to defend their real living standards compared with depreciation.

While depreciation means that imported goods and services rise in price (with exports falling in foreign prices), domestic residents have some scope to substitute away from the more expensive traded goods (except where there is total food dependency). No-one has to buy a Mercedes Benz in Latvia.

Further, the depreciation provides shelter to the import-competing local industries which is good for local employment growth. The inflationary consequences can be dealt with by appropriate policies (more about which in my promised blog on supply-side inflation).

But with domestic deflation (wage cuts and public sector job cuts) there is less flexibility. Most nominal contractual obligations are denominated in the local currency which means that households have to cut back elsewhere (which could include essentials) just to stay afloat as their nominal incomes are cut.

The UK Guardian says that the austerity solution uses poverty as the adjustment mechanism:

So do Greece, Ireland and perhaps Spain and Portugal understand just what they are being asked to emulate? How much “Latvian medicine” will these countries take? If their economies shrink and employment plunges, where will their labour emigrate?

Apart from the misery and human tragedy that will multiply in its wake, fiscal and wage austerity is economically self-destructive. It will create a downward demand spiral pulling the EU as a whole into recession. What is needed is a reset button on the EU’s economic and fiscal philosophy. Bank lending inflated its real estate bubbles and financed a transfer of property, but not much new tangible capital formation to enable debtor economies to pay for their imports.

Conclusion

I just don’t see that forcing your population into poverty is a policy anyone would advocate especially when the same policy redistributes real income to the higher income earners and those with wealth.

I also don’t think that a policy that aims to protect greedy banks which have pursued very imprudent “investment” strategies is a policy that any nation should follow.

That is all the time I have today and so …

That is enough for today!

Bill;

Michael Hudson of the U. of Missouri at Kansas City is an advisor to the Harmony (opposition) party in Latvia. His take on the election was that anti-Russian and generic anti-native propaganda allowed the government to eke out a very narrow victory. Harmony’s economic platform is a very interesting read, featuring conversion of outstanding debt owed to foreign banks into the local currency. Equivalent to FDR’s nullification of the gold clause in the 1930s.

Cheers.

One can note some of the comments to the Guardian article:

PhilipD

“… an ethnic Russian Latvian friend of mine here in Dublin (who works in a very low paid industrial job) told me that not just has she cancelled all plans to move home but that she is encouraging her siblings to come to Ireland – bad and all as it is in Ireland, she says, there are still jobs available for people willing to work hard and there is less of a threat of violence in the air.

I can only assume that if Latvians consider Ireland to be a better bet, then the country must really be in serious trouble.”

ennisfree

“A Latvian emigre (since about 6 months ago) told me that there are people there literally starving.

How much longer before the austerity contagion wreaks its havoc here.”

The coauthor of the Guardian article Jeffrey Sommers recently had an article in Counterpuch:

Latvia “Mind the Gap!”

http://www.counterpunch.org/sommers12102010.html

“Thousands have left Latvia to find work in the United Kingdom. Indeed, surveys of these migrants reveal that is not merely the inability to support themselves and family with the Latvian economic crisis that drives them to leave, but also the desire for dignity that escapes them in many Latvian jobs. Current data shows that Latvian workplaces are among the most dangerous in the EU and Latvian migrants report workplace abuse is all too common….”

Already before the present economic crises people that could did emigrate from Latvia and fertility rates was rock bottom. Then it was hailed as the neo-liberal model country. Those neo-liberals are truly sick and distorted people. How can a country where its young and working age inhabitants flee from and where they don’t want to have children be a model country, how sick is such ideological values.

Ireland is also suffering from an exodus of skilled people:

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/29/business/global/29austerity.html?_r=2

The results of neo-liberalism: depression, mass unemployment, a brain drain, falling birth rates, and poverty.

@Dale,

the Harmony Center coalition was backed mostly by Russians – and that always triggers a reflex of self-defense in the Baltics. There is no need for “anti Russian propaganda”. People there know their history well. It is really a shame that Harmony center could not establish themselves with Latvians.

So the job of neo-liberals was easy – all they needed was to stress who were the main backers of Harmony Center coalition (and scare with their alleged relations with Kremlin) – and that was enough to overshadow everything else. It is similar to bringing up terrorism in the US, or any other “open wound” issue that any nation and country has.

I have long admired Michael Hudson and as Dale mentioned, Hudson has a written often of the disaster that is unfolding in Latvia. Following are links to his Latvian articles.

http://michael-hudson.com/tag/latvia/

In my view, it is time well spent to read as many of his other pieces as possible (why even Max Keiser named him analyst of the year – again!)

http://maxkeiser.com/2010/12/20/analyst-of-the-year-award-again-dr-michael-hudson/

I think the situation in Latvia is much more dramatic!!!

After population census in Mart 2011 – found that Population of Latvia

decreased by 10% compared to what was believed in 2010 year.

http://www.stop.lv