I have received several E-mails over the last few weeks that suggest that the economics…

When will the workers wake up?

Early in the crisis I wrote this blog – The origins of the economic crisis – which set out some of the underlying dynamics of the neo-liberal era that had combined to establish the preconditions for the resulting collapse of the financial system. There was an interesting article in the UK Guardian on Tuesday (January 18, 2011) – The myth of ‘American exceptionalism’ implodes – by US academic Richard Wolff that bears on the themes I regularly discuss in my blog. The importance of the article is that it clearly outlines why the crisis emerged and further that the game is up – we cannot go back to where we were prior to the crisis. The reality is that a paradigm change is required and it is just a matter of which way things will go now. The signs are ominous that a conservative backlash is coming that will make the neo-liberal period look like a Sunday School picnic. But there is also scope for progressives to seize the moment. The problem is that there isn’t much going on in progressive land. The starting point should be a credible attack on the dominant macroeconomics – that is my little part of the story. Helpers needed.

The thesis I outlined in the earlier blog was broadly this. A defining characteristic of the neo-liberal era was the breach in the long stable relationship between real wages growth and labour productivity growth. This is a very important relationship. The only way that living standards can rise (distributional considerations aside) is if nations overall become more productive. That is, they find ways to generate more real output per unit of input which can then be shared around.

That productivity dividend provides the scope (or “room”) for workers to enjoy real wages growth without setting off any inflationary pressures.

As I outlined in this blog – Modern monetary theory and inflation – Part 2 – the distributional contest between labour and capital is over the real output that is available in any period.

If real wages grow in proportion with labour productivity growth then the share that workers get from national income (GDP) is constant over time. The constancy of the wage share was considered to be one of the great stylised facts of capitalism (Keynes called it “a bit of a miracle”). While there were cyclical deviations as the mark-up on costs was squeezed or expanded for years the wage share in most nations was fairly stable.

Former Cambridge economist, Nicky Kaldor (in his famous 1956 article – ‘Alternative Theories of Distribution’, Review of Economic Studies, 23, 83-100) coined the expression stylised fact in relation to the wage share and said:

… no hypothesis as regards the forces determining distributive shares could be intellectually satisfying unless it succeeds in accounting for the relative stability of these shares in the advanced capitalist economies over the last 100 years or so, despite the phenomenal changes in the techniques of production, in the accumulation of capital relative to labor and in real income per head.

There were disputes about how stable is stable and some sceptics tried to suggest that the wage share was in fact highly variable (Robert Solow for example). But, in general, there was shared view among economists that there was constancy and the task they saw was in explaining this “miracle”.

It meant that there was some sense of distributive justice in the system if workers who contributed to the productivity growth were able to share proportionately in it.

There was also the question of realisation – which relates to how certain the firms can be that the products they create in advance of sales will actually sell and their expected profits realised. If output per unit of labour input (labour productivity) is rising in line with the capacity to purchase (the real wage) then economic growth is also likely to sustain itself given the dominance of consumption in aggregate demand (total spending).

Certainly, there may still be fluctuations in investment spending in line with variations in sentiment among firms but the possibility of a realisation crisis (as identified for example by Marx) is reduced if you have full employment and real wages are growing in line with productivity.

At any rate, that was one of the features of the full employment era which was termed the Golden Age by some economists because living standards rose in line with productivity growth and workers enjoyed stable employment (mostly full-time). It wasn’t Shangri-La! Women and minorities were discriminated against and colonial exploitation was prominent. But the bad aspects of the system were cultural etc and not supporting the good outcomes enjoyed by the majority.

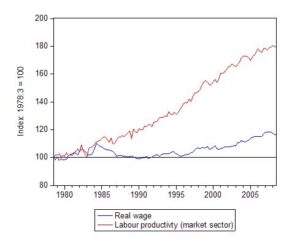

In the blog – The origins of the economic crisis – I produced a graph for Australia (as follows) which showed that real wages failed to track GDP per hour worked (in the market sector) – that is, labour productivity since 1980.

The previously stable relationship between the two was broken by a Labor government who engineered a real wages cut under a much-touted incomes policy which was really a stunt to redistribute national income back to profits in the vein hope that the private sector would increase investment. It was based on flawed logic at the time and by its centralised nature only reinforced the bargaining position of firms by effectively undermining the traditional trade union movement skills – those practised by shop stewards at the coalface.

This was the start of the neo-liberal period. What happened to the gap between labour productivity and real wages? The gap represents an increasing real output grab for profits and shows that during the neo-liberal years there was a dramatic redistribution of national income towards capital. The Australian government (aided and abetted by the state governments) helped this process in a number of ways: privatisation; outsourcing; pernicious welfare-to-work and industrial relations legislation; the National Competition Policy to name just a few of the ways. The result is that since that time the wage share has fallen continuously (and continues to fall).

In terms of the realisation issue mentioned above, these distributional trends clearly compromised the capacity of the economy to grow given that the system relies growth in spending to sustain itself? This was especially significant in the context of the increasing fiscal drag coming from the obsessive (and successful) pursuit of public surpluses which squeezed purchasing power in the private sector from around 1997 until the onset of the financial crisis.

In the past, the dilemma of capitalism was that the firms had to keep real wages growing in line with productivity to ensure that the consumptions goods produced were sold. But in the recent period, capital found a new way to accomplish this which allowed them to suppress real wages growth and pocket increasing shares of the national income produced as profits. Along the way, this munificence also manifested as the ridiculous executive pay deals and the growth of the financial sector which sowed the seeds for the ultimate meltdown that began in 2007.

The trick was found in the rise of “financial engineering” which pushed ever increasing debt onto the household sector. The capitalists found that they could sustain purchasing power and receive a bonus along the way in the form of interest payments. This seemed to be a much better strategy than paying higher real wages. The household sector, already squeezed for liquidity by the move to build increasing federal surpluses were enticed by the lower interest rates and the vehement marketing strategies of the financial engineers. The financial planning industry fell prey to the urgency of capital to push as much debt as possible to as many people as possible to ensure the “profit gap” grew and the output was sold. And greed got the better of the industry as they sought to broaden the debt base. Riskier loans were created and eventually the relationship between capacity to pay and the size of the loan was stretched beyond any reasonable limit. This is the origins of the sub-prime crisis.

All of that is background to an interesting article in the UK Guardian on Tuesday (January 18, 2011) – The myth of ‘American exceptionalism’ implodes – by US academic Richard Wolff who is well known for his incisive analysis of the dynamics of capitalism.

He notes that “(u)ntil the 1970s, US capitalism shared its spoils with American workers. But since 2008, it has made them pay for its failures”.

This is a common theme in my blog as well and strongly resonates with the ideas I outlined above and spelt out in more detail in the recent blog – Imagine if we treated humiliation itself as a cost. In that blog I highlighted that the major thrust of macroeconomic policy over the last 30 to 40 years has been focused on fighting inflation with output gaps via restrictive monetary policy.

Over that period, the commitment to full employment (enough jobs for all those who want them) was abandoned in favour of a lesser goal of full employability. The difference between the policy aspirations is fundamental – that is, it represents a major shift in paradigm. The full employment era was marked by governments manipulating demand to ensure spending was sufficient to elicit real output growth which at current productivity levels provided enough jobs for those who wanted them.

Unemployment was constructed as a systemic failure of the overall economy to generate enough jobs rather than being something that an unemployed individual could do very much about.

The full employability era abandoned that conception and instead considered unemployment to be an individual problem which required individual solutions – and so the era of hunting down the victims of the systemic failure began. Pernicious work-welfare type legislation, endless and meaningless training programs and the rest of the suite of supply-side programs defined the limits of government responsibility to the disadvantaged who had been locked out of gainful employment by a system that was starved of aggregate demand as a result of the renewed fiscal conservativism.

It is clear that during the full employment era, workers enjoyed not only stable employment which matched their preferences for working hours but they also enjoyed real wages growth in line with the capacity of the economy to pay this growth without generating inflation.

Wolff writes that:

One aspect of “American exceptionalism” was always economic. US workers, so the story went, enjoyed a rising level of real wages that afforded their families a rising standard of living. Ever harder work paid off in rising consumption. The rich got richer faster than the middle and poor, but almost no one got poorer. Nearly all citizens felt “middle class”. A profitable US capitalism kept running ahead of labour supply. So, it kept raising wages to attract waves of immigration and to retain employees, across the 19th century until the 1970s.

The US was not exceptional in this sense. The capacity to enjoy rising standards of living came from the ability of the workers to share in the growth of labour productivity, which was a world trend as noted above.

Wolff notes that sometime in the 1970s, this American dream “began to die” because:

Real wages stopped rising, as US capitalists redirected their investments to produce and employ abroad, while replacing millions of workers in the US with computers. The US women’s liberation moved millions of US adult women to seek paid employment. US capitalism no longer faced a shortage of labour.

This was a common trend and is not specifically confined to the dynamics of American capitalism. Most advanced economies to varying degrees fell prey to the neo-liberal resurgence which reinstated the crackpot ideas to the centre stage of policy formulation even those these very same ideas had been shown to be categorical failures during the Great Depression.

But it is clear that US employers like employers in most nations took advantage of the changing global environment and operating with complicit governments who were by now under the spell of the neo-liberals and “stopped raising wages” and cut benefits in general. All this was done under the umbrella of mass unemployment which shifted the bargaining power firmly to the employers.

Wolff notes that as a result:

… the vast majority of US workers have, in fact, gotten poorer, when you sum up flat real wages, reduced benefits (pensions, medical insurance, etc), reduced public services and raised tax burdens.

This is not a controversial finding. But it does leave me amazed when I hear US workers speaking in jingoistic ways about how wonderful their nation is. They have been living in a nation that has systematically swindled them and handed over their labour to gamblers. More so than most nations in fact.

Wolff says that the other side of the coin is that the “rich … have got much richer since the 1970s, as every measure of US income and wealth inequality attests”.

Why has this happened? Simple:

… while workers’ average real wages stayed flat, their productivity rose (the goods and services that an average hour’s labour provided to employers). More and better machines (including computers), better education, and harder and faster labour effort raised productivity since the 1970s. While workers delivered more and more value to employers, those employers paid workers no more. The employers reaped all the benefits of rising productivity: rising profits, rising salaries and bonuses to managers, rising dividends to shareholders, and rising payments to the professionals who serve employers (lawyers, architects, consultants, etc)

As above for Australia and many nations. As I noted at the outset – this is one of the characteristic hallmarks of the neo-liberal era – to engineer a major redistribution of real income away from workers and to use government agency to reduce the capacity of workers to do anything about it.

The combination of mass unemployment, harsh industrial relations and welfare laws, and anti-union legislation combined to undermine the capacity of the workers to defend their shares in real income.

But as I noted above and it is a point that Wolff also makes – the proof is in the pudding and it has turned out to be a very bitter pudding. Under the smokescreen of support from mainstream economists – governments blithely set about undermining the conditions for prosperity. We were told the “business cycle is dead” and we were in the era of the Great Moderation – Please read my blog – The Great Moderation myth – for more discussion on this point.

But as workers became more indebted and the financial engineers greedily and with fraudulent practices extended their credit push beyond the margin of those who could reasonably be expected to pay the filthy harvest was approaching. Those who wrote from the perspective of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) as well as a few others saw it coming. We were writing about these trends in the 1990s. But the mainstream hold on the media and the public fora meant that the message was lost in the self-congratulation that economics had solved the macroeconomic problem.

It was painful to live through that period as an alternative economics thinker. I was often invited to be a key note speaker at conferences and typically after my talk I would be attacked by the usual sic-dogs in my profession with all the tom-foolery that constitutes mainstream macroeconomics. The attacks were always to humuliate me and to make me look stupid. My skin is thick and water flows of me like a duck but the sadness was that governments didn’t listen.

It was only a matter of time and when it hit the game was up.

Once workers stopped borrowing and spending as a reaction to finally realising they were carrying “unsustainable levels of debt” the game was up. The financial engineering had nowhere to go and the real wages-productivity gap finally generated the realisation problem that was only temporarily delayed by the mass consumption driven by the credit binge.

The neo-liberal model of capitalist development failed at that point. It is a flawed growth strategy. It can only promote growth by creating dynamics which soon enough reverse and the stocks that build up during that period (debt, labour underutilisation etc) make the resulting crisis larger than otherwise.

Wolff notes that the behaviour of the “rich” in the lead-up to the crisis ensured that it would happen:

The richest 10-15% – those cashing in on employers’ good fortune from no longer-rising wages – helped bring on the crisis by speculating wildly and unsuccessfully in all sorts of new financial instruments (asset-backed securities, credit default swaps, etc). The richest also contributed to the crisis by using their money to shift US politics to the right, rendering government regulation and oversight inadequate to anticipate or moderate the crisis or even to react properly once it hit.

The remarkable thing is that the workers are now so benign in most nations that they are standing idle while these destructive dynamics resume with the nascent growth that is finally emerging on the back of the fiscal injections.

In the US (according to Wolff), the rich have “utilised both parties’ dependence on their financial support to make sure there would be no mass federal hiring programme for the unemployed (as FDR used between 1934 and 1940)” and pressured governments to focus on policy that “would benefit banks, large corporations and the stock markets”.

But they cannot fully recover unless the workers start spending again. Ultimately, the parasitic and unproductive financial sector requires a real economy to boom to provide the growth in real goods and services with which we measure rising living standards. Real living standards, as noted at the outset, require productivity growth and that is found in the real economy. The improved transformation of inputs into outputs.

The machinations of the rich lobby groups to get widespread deregulation was designed to make it easier for their interests to expropriate real income.

At present there is very little real income generation – borrowing is low so banks are struggling and firms are not selling much so profits are lower than what they might be.

The reality is that we will not sustain a recovery if we go back down the neo-liberal path. Fiscal austerity will fail to deliver what the devotees of Ricardian Equivalence have forecast (a private spending boom as consumers and firms become relieved by the lower budget deficits). The British experiment will fail and already unemployment is rising there as the economy contracts.

There was one part of Wolff’s story- the macroeconomic part – that I didn’t accept and which reveals him to be less enlightened about the way the monetary system operates, specifically the way a sovereign government can operate. He said that:

… the current drive for government budget austerity – especially focused on the 50 states and the thousands of municipalities – forces the mass of people to pick up the costs for the government’s unjustly imbalanced response to the crisis. The trillions spent to save the banks and selected other corporations (AIG, GM, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, etc) were mostly borrowed because the government dared not tax the corporations and the richest citizens to raise the needed rescue funds. Indeed, a good part of what the government borrowed came precisely from those funds left in the hands of corporations and the rich, because they had not been taxed to overcome the crisis. With sharply enlarged debts, all levels of government face the pressure of needing to take too much from current tax revenues to pay interest on debts, leaving too little to sustain public services. So, they demand the people pay more taxes and suffer reduced public services, so that government can reduce its debt burden.

While we might be kind to Wolff and conclude that he is referring to the current institutional realities in the US which place voluntary constraints on the national government (to act as if it was still pre-1971 and operating within a convertible currency, fixed-exchange rate monetary system) I actually think he was rather rehearsing the erroneous mainstream line about government budget constraints.

The US government didn’t have to tax the richest citizens and corporations “to raise the needed rescue funds”. The central bank has clearly shown it can buy whatever it wants in the private markets by crediting bank accounts. The US Treasury could do exactly the same and if the current legislative rules require it to undergo some gymnastics that make it look like it cannot then the progressives like Wolff should be focused on undoing those ridiculous constraints.

The progressive challenge should be focused on why the US government chooses to deny its own capacities in the fiat currency system that it operates (and dominates given its currency-issuing monopoly). I am disappointed that Wolff chose to run the mainstream line here.

But then as you read further it gets even worse. Yes the government just “borrowed … precisely from those funds left in the hands of corporations and the rich” – that is, they just borrowed what they spent – as always. The mainstream economists cannot get their heads around the fact that it is a wash – governments spend, then borrow what they spend – as a monetary operation. It has nothing to do with the government not taxing the rich and therefore they have funds that the government can borrow before they spend. That is mainstream nonsense.

Finally, Wolff’s focus on “sharply enlarged debts” at “all levels of government” is a disgrace – for a progressive. He seems to think that this means that the US government is taking “too much from current tax revenues to pay interest on debts, leaving too little to sustain public services”.

Where in the accounting system – voluntary constraints notwithstanding – would we find that causality. There is not doubt that the failed political processes and lack of leadership at the top in the US are forcing fiscal austerity. But the US government doesn’t have to reduce spending to pay for interest on debt.

A very poor finish to an otherwise interesting article.

Empirical diversion

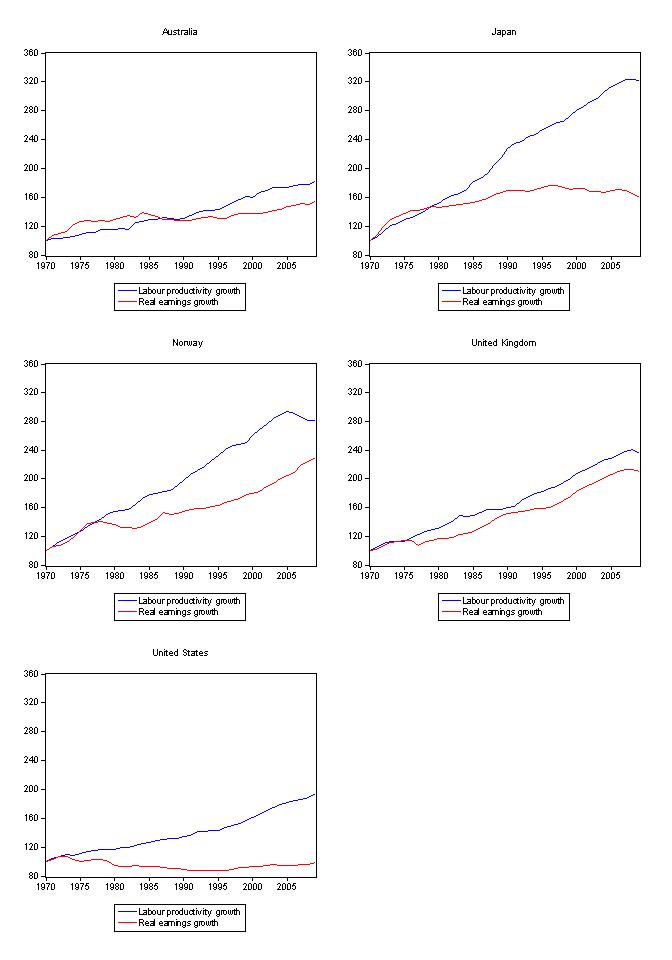

To give you some idea of what happened during this period I compiled the following graph. It shows index numbers (1970=100) for Real Earnings and Labour Productivity to give you some idea of how each has grown over the last 40 years. I chose Australia, Japan, Norway, the UK and the USA for comparison being a broad selection of different types of economies.

While the relationship between real earnings growth and labour productivity growth over this period is interesting in itself for each individual country, I also set equivalent vertical axis scale so you can also compare between countries.

You can see that in the nations shown real wages growth has lagged behind labour productivity growth (to varying degrees). You also see that workers in Norway have enjoyed much better outcomes than workers elsewhere. The US stands out clearly as the worst performed nation.

Conclusion

The reality is that we will not sustain a recovery if we go back down the neo-liberal path. A fundamental shift in our thinking and practice needs to occur if we are to enjoy sustained and inclusive growth.

National governments cannot continue to be agents for capital – undermining full employment and legislating against workers’ interests. Some of you will scream – “so, you are advocating socialism” – which only tells me that the education system has failed you.

I might advocate socialism but that is not what I said in the last paragraph. Even within the property ownership relations we define as capitalism you cannot base a growth strategy on increasingly pushing the workers into debt so they can continue to consume while at the same time redistributing the products of their labour in increasing proportions (and therefore quantities) to capital.

All the supporting machinery that has allowed that to happen over the last 30 or so years also has to be jettisoned.

That is enough for today!

“I might advocate socialism but that is not what I said in the last paragraph. Even within the property ownership relations we define as capitalism you cannot base a growth strategy on increasingly pushing the workers (MY EDIT: the many) into debt so they can continue to consume while at the same time redistributing the products of their labour in increasing proportions (and therefore quantities) to capital (MY EDIT: the few).”

Yes, most economists can if they assume aggregate demand is unlimited and therefore if workers save and later retire (accumulate a lot of leisure), then there will be a shortage of workers in the future.

That is what debt can do (BOTH gov’t and private). It is spend now, and if wages don’t rise enough in the future, work later. That work later can get to the point of no retirement.

“we cannot go back to where we were prior to the crisis.”

Then someone needs to explain the differences between “price inflating” with currency, “price inflating” with gov’t debt, and “price inflating” with private debt.

By “price inflating”, I mean either creating more medium of exchange or attempting to create more medium of exchange.

Very interesting post, Bill. I have a couple of questions: (1) What is your opinion of the effect of globalization of labour markets on driving the gap between GDP growth and wages growth? (2) Is there any downward pressure on wages caused by demographics?

“The employers reaped all the benefits of rising productivity: rising profits, rising salaries and bonuses to managers, rising dividends to shareholders, and rising payments to the professionals who serve employers (lawyers, architects, consultants, etc)”.

As per usual with Bill, a false dichotomy between labour and capital. The landlord or rather “rentier”, not the capitalist class, has reaped most of the benefits – over a third of peoples’ wages and income goes to either servicing mortgages or rents. A lot of landlords use rents to pay off their own mortgage. Moreover, most profits and investment is often in “land” and “real estate” (enter the lawyers and architects) and our tax system taxes wages, rather than those who are asset-rich but income poor.

Marx, in one of the last pages he wrote before his death, FINALLY got this point when he said landlords were an “alien force” on capitalism, arguing:

“in the same proportion as [surplus product] develops, landed property acquires the capacity to capture an *ever-increasing portion* of this surplus value by means of its landed monopoly and thereby, of raising the value of its rent and the price of the land itself. The capitalist still performs an active function in the development of this surplus value and surplus product. But the landowner need only appropriate the growing share in the surplus product and the surplus value, without having contributed anything to this growth”

Although earlier Marx conceded that “in present-day society the instruments of labour are the monopoly of the landowners and the capitalists” , later he noted “the capitalist finds that his capital ceases to be capital without wage labour, and that one of the presuppositions of the latter is not only landed property in general, but modern landed property; landed property which, as capitalized rent, is expensive, and which, as such, excludes the direct use of the soil by individuals. Hence Wakefield’s theory of colonies, followed in practice by the English government in Australia. Landed property is here artificially made more expensive in order to transform the workers into wage workers, to make capital act as capital . . .”

Marx appreciated that if land were not privately monopolized, men would be able to live as free individuals. This was the conviction behind the following statement: “The nationalization of land will work a complete change in the relations between labour and capital, and finally, do away with the capitalist form of production, whether industrial or rural” and that “The mere legal ownership of land does not create any ground-rent for the owner. But it does, indeed, give him the power to withdraw his land from exploitation until economic conditions permit him to utilize it in such a manner as to yield him a surplus, be it used for actual agricultural or other production purposes, such as buildings, etc. He cannot increase or decrease the absolute magnitude of this sphere, but he can change the quantity of land placed on the market. Hence, as Fourier already observed, it is a characteristic fact that in all civilized countries a comparatively appreciable portion of land always remains uncultivated. Thus, assuming the demand requires that new land be taken under cultivation whose soil, let us say, is less fertile than hitherto cultivated-will the landlord lease it for nothing, just because the market-price of the product of the land has risen sufficiently to return to the farmer the price of production, and thereby the usual profit, on his investment in this land? By no means. The investment of capital must yield him rent. He does not lease his land until he can be paid lease money for it. Therefore, the market price must rise to a point above the price of production, i.e., to P + r [price of production plus rent] so that rent can be paid to the landlord”.

Neo-liberalism isn’t liberalism; it’s “neo-feudalism” as Michael Hudson puts it.

Looking at your second set of charts, it is easy to see what the Labor government of the mid-80’s was concerned about: real earnings growth in Australia had been getting ahead of productivity growth. The other thing I find interesting is the low productivity growth in Australia compared with some other nations. Is this because our productivity was higher to begin with, or were we starting from a similar base and have failed to improve as rapidly? If so, why?

Another notable point is the extent to which the US is an outlier. Productivity growth there has not been that great, but real wages have gone down. Japan is also notable, first for its great productivity growth, second for the extent to which wages growth has lagged. I would say from those charts that the UK, rather than Norway, has been an exemplar. The gap between productivity and wages growth has never been large.

How do you account for real earnings growth in the UK being somewhat better and closer to productivity growth than in other nations?

Obviously the US record is shockingly bad.

But the record of British New Labour (strangely? given their neoliberalism) on real wages growth doesn’t look too bad in your graph.

Have I missed something?

Thanks for another great post,

Regards,

Andrew

Also, what is your opinion of the Hawke Labour government’s Prices and Incomes Accord (in its various forms: Mark II, Mark III, Mark IV etc)?

Would you characterise this policy as neoliberal or a Post Keynesian incomes policy?

I really would appreciate any answer or help with these questions.

Thanks

@ Andrew I’d say neoliberal: it assumes prices lead wage increases. Casuality, for the most part, shows wage increases occur before price increases. W —-> P. It’s an endogenous money world. It adjust wages in accordance with prices, rather than adjusting prices with wages (at least that was my understanding of it).

Bill, You refer to “Pernicious work-welfare type legislation, endless and meaningless training programs”. Well JG has a workfare element: “turn up for work else you don’t get paid”. Plus JG as it is normally set out, involves training.

The advocates of JG gaily tell us that every unemployed person can be allocated to a JG project. Correct in theory. But, I suggest the advocates of JG have totally failed to work out the details, or tell why JG will be any better than the above “pernicious” legislation or “meaningless training programs”.

Dear Ralph (at 2011/01/20 at 21:46)

We have spent years considering those questions and you might like to read this report we issued in 2008 – Creating effective local labour markets: a new framework for regional employment policy. It will disabuse you of some of your prejudices and show you that statements like “the advocates of JG have totally failed to work out the details” are may I say it “totally” false.

There is no workfare element in the JG. It is like any job – work and be paid. The coercion you refer to is the capitalist labour market. The system is coercive of the freedom of those who do not own capital and thus have independent means of income.

best wishes

bill

Or looking at it another way there is a workfare element in every employment position. “If you want a living income you must hand over a full week of your limited life in return” is the underlying assumption of all these systems – both actual and proposed.

I was wondering whether this underlying assumption is based on actual evidence or whether it is just a political reality given our current level of social development as a species.

If we split real output into two: ‘wants’ and ‘needs’ – with ‘needs’ being the minimum amount of real output required to ensure everybody in the population has the minimum acceptable standard of living.

You then take ‘needs’ factor in the productivity level of the economy and that’s how much time you need from everybody to create the ‘needs’.

So with a bit of luck productivity will advance ahead of ‘wants’ becoming ‘needs’ and the amount of time required of everybody to produce the basics should decrease.

Is the current time required from everybody still a full week on that basis?

Im sure most of the differences between countries are due to the labor unions.

Bill, The work you refer to (Part 4, Job Guarantee section) says “any offer of a suitable job paying at or above the legal minimum wage, including a JG job, would terminate the income support payment.” I.e. if you are on some benefit other than JG and refuse the JG job your benefit gets cut. That equals workfare, or at least a workfare element (on my understanding of the word “workfare”). Btw I don’t object to workfare. I just believe in calling a spade a spade. I.e. if a system has a workfare element, then let’s be open about it.

Another contradiction is thus. The wage is suggested as being around the minimum wage, but it says “The nation always remains fully employed”. I suggest that very roughly half the unemployed currently turn their noses up at minimum wage work, and would do likewise under JG. Thus JG does not achieve full employment (unless you enforce the workfare element: “take any job you can do at the minimum wage else your benefits get cut”.)

Having said that, I support something along the lines of JG. But the details need thinking out better.

Well, Ralph, if that’s the definition of workfare, then I’d much rather have that then a system that pays people more not to work. Your quote from Bill sounds like a good idea to me, much better than the alternative.

“I suggest that very roughly half the unemployed currently turn their noses up at minimum wage work”

In the UK there are 480,000 vacancies and 4.8 million out of work, so that is a mathematically impossible opinion.

If you have a system where the assumption is that people work to get an income, and there are more jobs that people why shouldn’t you require people to work? It’s not ‘workfare’, it’s just work. That’s the deal.

In this system why should some people get access to resources for nothing in return and others do not?

Another great post! Thanks! I’m noticing that this problem is attracting more and more attention in the US. Good! Just today I read a post from Mike Konczal (Rortybomb) and Nick Krafft (Open Economics) about the same subject. But the real problem is nailed down by a Freddie deBoer: there are no serious lefties in the US to engage with the conservative right pseudo “mainstream”. The people who represent left and/or progressive position in the US are mostly apologists who end each alleged challenging sentence with a very long addendum starting with a big “but”.

DEL_this_part_http://lhote.blogspot.com/2011/01/blindspot.html

Bill, thanks for putting up the comparative graphs, I’ve wondered what the UK was, although not as bad as Australia, it still looks like we’re due a 20% pay rise!

On another UK issue, I’ve looked but can’t seem to find any UK pro-MMT institutions, presumably some of Wynne Godley’s colleagues at Cambridge?

I’ve got a nephew studying Economics at Reading, how good is that ‘institution’?

Additionally my daughter is studying Economics at A Level, my step-son is thinking about it and my son pretty keen too.

Any advice as to how to keep them unpolluted by ‘lame-stream’ economics?

Dear Bill,

When I look at the Real Earnings and Labour Productivity graph for Australia the thought cam e to me someone could use this (or could they?) to argue that this helps to underpin the argument that it was wage increases during the period 1970 to 1985 which caused the high inflation (I’m not sure to what extent there was high inflation at that time having been over seas then) during that period. The real wage increase during that period is higher than the productivity growth. Can you knock this argument out for me, please?

Thanks

Graham

Of course I realise that there were the externally created oil price shocks as well. In addition many argue that Gough’s wild borrowing and spending contributed.

Ralph, you stated the following…

“I suggest that very roughly half the unemployed currently turn their noses up at minimum wage work, and would do likewise under JG. Thus JG does not achieve full employment (unless you enforce the workfare element: “take any job you can do at the minimum wage else your benefits get cut”.)”

You ‘think’ this way because this is a result of the marginalisation and demonisation of unemployed as failed individuals. When we had full employment policies, people electing to not work, i.e. thumbing their noses up at minimum wage jobs was tiny. In 1950, just over 2,500 people in Australia were on the dole. Everyone else elected to work. Unless of course you subscribe to a theory of generational superiority back then.

Also….

“Having said that, I support something along the lines of JG. But the details need thinking out better.”

Details are well thought out, everyone can be doing something of value. The WWII populace figured this out and in fact refused to not have full employment. While soliders were away, all remaining labour resources were deployed. previous wars, such as post-WWI demoblisation saw some employment dislocation, but the view point was clear by 1945/6. Everyone can be doing something and receiving a pay. The population previously getting weapons and killing other soliders could do something else, ANYTHING else. It could also be without the cause of death and destruction of real wealth.

I havne’t read Bill’s work, but i can easily imagine JG jobs. Firstly you have to do tasks where it is suitable to have an insufficnet labour force when the private sector does the task. So building a higway until it is only 60% complete is just as useful as one that is zero percent complete. However something like environmental rehabitliation would be suitable, planting flora that regenerates swamp land and reverses salinity would be a good one.

The private sector will not place a value on such activity, and with my above example, 60% of flora planted before they leave for private sector jobs is better than nothing.

Sorry I’ll rephrase this line..

“Firstly you have to do tasks where it is suitable to have an insufficnet labour force when the private sector does the task”

To..

“Firstly you have to do tasks where it is suitable to have an insufficient labour force when the private sector takes labour away for it’s own tasks.”

In response to Will Richardson’s questions:

I’ve got a nephew studying Economics at Reading, how good is that ‘institution’?

Additionally my daughter is studying Economics at A Level, my step-son is thinking about it and my son pretty keen too.

Any advice as to how to keep them unpolluted by ‘lame-stream’ economics?

I would suggest Steve Keen’s book “Debunking Economics” for inoculation purposes. It points out some of the big problems with the neoclassical school (among others) in a very readable manner. You don’t want them to totally reject mainstream theories otherwise they won’t be able to pass their exams. However instilling a healthy scepticism is no bad thing and that book should do the trick.

Bill,

I have read quite a bit of your work lately and a common theme seems to be the idea that the government needs to spend varying amounts, ensuring enough is spent to maintain an adequate level of aggregate demand in order to promote full employment.

Question: Can you name me some countries governments that:

a. have/are spending too much and have created excess aggregate demand

b. have/are spending pretty much the correct amount given the circumstances

Derek, thanks for that, passing the exams was on my mind too!

Alex, I’d say Norway comes closest with it’s Youth/Job Guarantee up to 24 and from 26 weeks unemployment, muddied by the huge trade and government surpluses, but bear in mind high net trade inputs to demand are balanced by the high tax/budget surplus.

I think the seemingly benign UK graph of earning growth vs productivity growth may cover up some nasties. I’d prefer graphs of median wages rather than the total or mean value that these graphs seem to show. The UK has a disproportionately large finance sector. It doesn’t take many hedge fund managers earning >£1B per year to skew the mean value away from a falling median wage.

Interesting take on this, Bill. But I have a question – do the real earnings growth numbers include benefits, such as health care? That’s relevant for the US since employers normally fund health coverage.

Bill, I thought you would find this article in “The Nation” interesting, as it is about Frances Fox Piven and her efforts toward a Guaranteed National Income. A job guarantee would be better, but to get an idea of how people in the US react to such proposals, you should read this and if you have the stomach, also read Mr. Beck’s original rant.

http://www.thenation.com/article/157900/glenn-beck-targets-frances-fox-piven

Bill:

There is another view on this. My brother-in-law (smart guy) pointed me to the US ECI data, and the story seems to be very different. It shows that real wages and benefits paid by employers increased by 27% from 1980 to 2005. Yes, capital did still capture the majority of productivity gains, but the US result isn’t nearly as abysmal as presented here.

So why prefer one series over the other? Yes, you could argue that FICA included in ECI does not benefit current workers. But that would ignore the fact that the real cost of labor employed by corporations has risen over the last several decades.

Date ,ECI % Change ,CPI % Change ,Real ECI (1980 = 100)

1981 ,9.7% ,8.6% ,101.01

1982 ,6.6% ,3.8% ,103.74

1983 ,5.5% ,3.3% ,105.95

1984 ,4.7% ,3.6% ,107.07

1985 ,4.1% ,3.6% ,107.59

1986 ,3.1% ,0.6% ,110.26

1987 ,3.4% ,4.5% ,109.10

1988 ,4.8% ,4.4% ,109.52

1989 ,4.8% ,4.5% ,109.83

1990 ,4.6% ,6.1% ,108.28

1991 ,4.4% ,2.8% ,109.97

1992 ,3.4% ,2.5% ,110.93

1993 ,3.7% ,2.6% ,112.12

1994 ,3.2% ,2.7% ,112.67

1995 ,2.5% ,2.5% ,112.67

1996 ,3.1% ,3.3% ,112.45

1997 ,3.3% ,1.5% ,114.44

1998 ,3.5% ,1.6% ,116.58

1999 ,3.5% ,2.7% ,117.49

2000 ,4.5% ,3.4% ,118.74

2001 ,4.3% ,1.3% ,122.26

2002 ,3.3% ,1.4% ,124.55

2003 ,4.0% ,2.2% ,126.74

2004 ,3.7% ,2.6% ,128.10

2005 ,3.0% ,3.5% ,127.48

No one is interested in a government data set that leads to a different conclusion? Oh, well. I’d suggest that the series that Bill used may reflect how workers in the US feel. They probably don’t perceive higher taxes paid by employers as benefiting them, but they are a legitimate cost faced by employers.

Here’s an interesting study by Martin Feldstein that refutes the conclusion above:

http://www.nber.org/feldstein/WAGESandPRODUCTIVITY.meetings2008.pdf

And a quote from the article:

Two principal measurement mistakes have led some analysts to concludethat the rise in labor income has not kept up with the growth in productivity. The first of these is a focus on wages rather than total compensation. Because of the

rise in fringe benefits and other noncash payments, wages have not risen as rapidly as total compensation. It is important therefore to compare the productivity rise with the increase of total compensation rather than with the increase of the narrower measure of just wages and salaries.

The second measurement problem is the way in which nominal output and nominal compensation are converted to real values before making the comparison. Although any consistent deflation of the two series of nominal values will show similar movements of productivity and compensation, it is misleading in this context to use different deflators for measuring productivity and real compensation.

Perplexed, it is all about distribution and averages. An investment banker compensation is huge but those at the lower end often get zero because minimum wage is minimum wage. And it is those at the lower end who generate most of activity in the economy. At the end of the day, GDP equals spending and GDP equals income whether nominal or real. It is absolutely pointless to argue that average income does not grow in line with average productivity. Statistics is big lie if you take it face value. So Feldstein is a liar. At best an innocent one.

Sergei – yes, the distribution matters. But the numbers in Bill’s blog are averages, too. I just want to understand this better. Clearly the wealthy in America have done very well over the last few decades. And the poor – many of whom suffer from chronic unemployment – have been hammered. That’s why I’d prefer to see a good analysis done by income percentiles or deciles. Anyone know of such a study?

Here’s an interesting quote relayed by my stats professor:

“If you have one foot in a bucket of ice and another in a bucket of boiling water, on average you’re perfectly comfortable. In that sense, we’re very comfortable with inflation right now. ”

~ Anirvan Banerji