I have received several E-mails over the last few weeks that suggest that the economics…

Tick tock tick tock – the evidence mounts

I have said it before that when the facts get in the way of mainstream economic theory – which is just about always – the professors (my peers) tell their students that the facts are wrong. They have a pathological obsession with hanging on to their theories. Apart from the arrogance that accompanies this I have never really been able to work it out. As a tenured professor I could overnight become an adherent of the Austrian School or whatever and my job wouldn’t be threatened. A tradesperson who loses his/her skills has a problem. But academic life is different. We can explore new ideas any time we choose and take time to develop the news skills commensurate with these ideas. That, in part, is what research is all about. So it is more about their unwillingness to let go of what are essentially religious beliefs that leads the mainstream economists to constantly pump out rubbish and lie when they are found out (by the facts). The overwhelming fact is that the push for austerity is not based on any evidence-based understanding of how the system works. It is driven by stylised economic models that bear no relation to the real world and fail when confronted with data from the real world. As the clock ticks by – tick tock tick tock – the evidence mounts that nations that introduce austerity fare poorly.

I thought this article in the New York Times (February 22, 2011) – Why Budget Cuts Don’t Bring Prosperity – was interesting.

The writer David Leonhardt points out that all the austerity proponents seized on news that Germany had started to grow strongly in the second quarter 2010 as evidence that the:

… American stimulus had failed and German austerity had worked. Germany’s announced budget cuts, the commentators said, had given private companies enough confidence in the government to begin spending their own money again.

It is always better when involved in the game of economic commentary to: (a) have a good understanding of the way things operate; and (b) notwithstanding that, to be relatively cautious before you pronounce a trend. It is always better to wait a few quarters before you assume that something is consolidating.

The first requirement – a good understanding of the way things operate – had me concluding that Germany’s growth resurgence was probably the result of the fiscal stimulus modest though it was. Given that Germany trades extensively in the Eurozone, I also concluded that there is so many negative portents coming from that area that as the fiscal stimulus was being withdrawn Germany would also flag a bit.

But I also thought it was better to wait before making any definite conclusion because it was possible that Germany had succeeded in eking out new export markets in China and India which might have given it a sustained growth boost. Remember they are still running budget deficits so there is an on-going stimulus coming from public net spending.

The tendency – no certainty – that the deficit terrorists will “jump on any data that helps them” makes me laugh. They conveniently ignore Ireland and now Britain. Germany was their miracle baby and they were milking it for what it was worth.

As David Leonhardt tells us – with just a hint of “I told you so”:

Well, it turns out the German boom didn’t last long. With its modest stimulus winding down, Germany’s growth slowed sharply late last year, and its economic output still has not recovered to its prerecession peak. Output in the United States – where the stimulus program has been bigger and longer lasting – has recovered. This country would now need to suffer through a double-dip recession for its gross domestic product to be in the same condition as Germany’s.

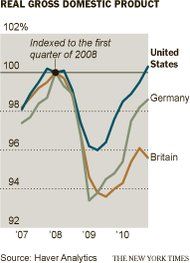

The New York Times article provided this graph which shows the evolution of real GDP (indexed to 100 at March 2008) for the United States, the United Kingdom and Germany to demonstrate that “the German boom didn’t last long. With its modest stimulus winding down, Germany’s growth slowed sharply late last year, and its economic output still has not recovered to its pre-recession peak. Output in the United States – where the stimulus program has been bigger and longer lasting – has recovered”.

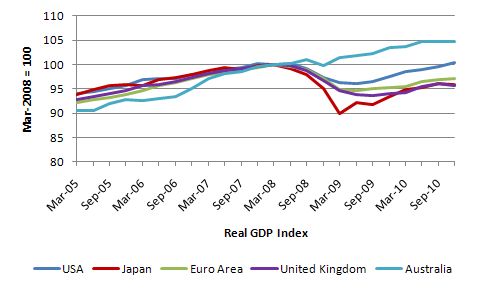

The next graph is my version of the NYT graph so as to include a few more nations. The same design principle is used – Real GDP is indexed to 100 in the March quarter 2008. All the data is taken from the OECD Main Economic Indicators (http://www.oecd.org).

Of the nations compared, only the US and Australia are now back to the levels of GDP at the time the crisis began. Australia, courtesy of a very significant and timely fiscal stimulus, clearly had a slight slow down and has since maintained growth. However, even in the case of Australia, the withdrawal of the fiscal stimulus (record mining boom notwithstanding) has seen growth stall and start flat lining. But the other three nations are still mired in real GDP levels well below the pre-recession levels.

I thought it would be useful to examine the relative labour market performance as well and it is here that interesting results are seen.

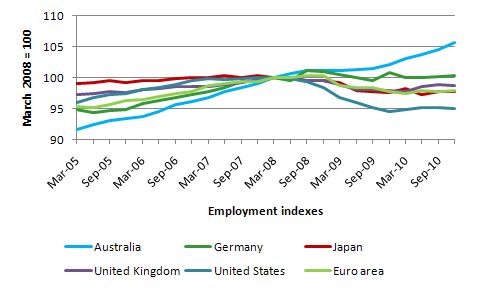

The next graph provides the same comparison (but with Germany included separately now due to data availability) using total employment (seasonally adjusted). The index is set at 100 for the March quarter 2008. If I had have made the scales of the vertical axis comparable then you have lost some of the detail but you would have seen that the variance of employment was lower than Real GDP (that is, it fluctuated within a narrower band).

I note that the employment indexes do not take into account underemployment (tendency for a rising proportion of part-time jobs to under-provide hours relative to the preferences of the labour force). Clearly, Australia’s superior real GDP performance is mirrored in its relative employment performance.

While Germany has not succeeded in reaching its pre-recession real GDP levels it managed to insulate employment from the output collapse.

The stand out is the US which shed jobs dramatically as real GDP plummeted and as real growth has returned the recovery in the jobs market is virtually non-existing. There is a crying need for direct job creation schemes in the US to address this tendency to grow without jobs.

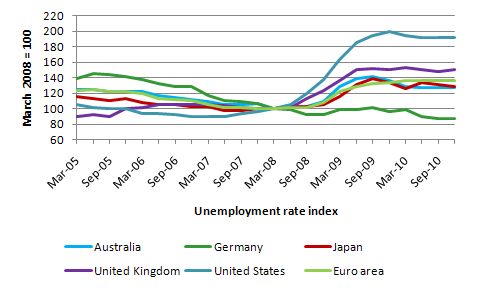

Finally, the next graph provides the same comparison using the unemployment rate (seasonally adjusted). As before the index is set at 100 for the March quarter 2008.

Germany once again is the only nation of those compared that has been able to insulate its unemployment rate from its real GDP loss. The analogue of the employment collapse in the US is the very stark rise in the unemployment rate since March 2008. The United Kingdom is also a poor performer in that regard.

The two nations that are now leading the charge in austerity – the UK and the US – have severely debilitated labour markets and show very little sign that any nascent growth to date – which has been driven solely by the public stimulus – has provided any tangible benefits to the labour market.

The worry is that with the UK and the US already locked into a residual high unemployment as a consequence of their inadequate fiscal responses to the private spending collapse in 2008 and 2009, as the fiscal austerity bites, their unemployment rates will ratchet up again. Already, they are experiencing rising long-term unemployment given how long the labour market has been depressed.

I saw a news alert from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics today which says that mass layoffs rose in the last month.

I heard a podcast yesterday (February 23, 2011) – The Business podcast: Youth unemployment – that relates that “One in five adults under 25 are out of work” in Britain and this group are becoming a “lost generation”. The push for austerity will reinforce that malaise.

I also saw a program on ABC TV the other day (Foreign Correspondent) – Goodbye, My Ireland – which documented the flood of young Irish workers who are moving to Australia (mostly) because there are zero prospects for work in the Ireland in the coming years. So the unemployment rate, already massive, is being held down by supply exits to other countries. Some government leadership!

Leonhardt makes a reasonable point that if there is poorly targetted or inefficient government spending in the US then a fierce political debate can help to make cuts where the spending is not advancing public purpose (my words). He actually said:

If the economy were at a different point in the cycle – not emerging from a financial crisis – the coming fight over spending could actually be quite productive. Republicans could force Democrats to make government more efficient, which Democrats rarely do on their own. Democrats could force Republicans to abandon the worst of their proposed cuts, like those to medical research, law enforcement, college financial aid and preschools. And maybe such a benevolent compromise can still occur over the next several years.

This would only be viable if the economy was at full capacity and the spending cuts were going to ease inflationary pressures. There is no room for net public spending cuts in the US at present. I would alter the composition of spending rather drastically over time but at present I would be adding to net spending as I re-arrange the deck chairs.

Leonhardt clearly understands that now is not the time to be making major public spending cuts:

The immediate problem, however, is the fragility of the economy. Gross domestic product may have surpassed its previous peak, but it’s still growing too slowly for companies to be doing much hiring. States, of course, are making major cuts. A big round of federal cuts will only make things worse.

Exactly. Spending equals incomes. If you cut spending you cut income and those cuts multiply throughout the economy creating even larger reductions in overall spending. Spending cuts now will severely damage and already struggling labour market in the US. It is madness to contemplate such cuts.

The US politicians should only be arguing about how large the spending impulse should be to directly create jobs. That is the only valid political challenge facing the US at present.

I particularly liked Leonhardt’s take on Ricardian Equivalence. He says:

Let’s start with the logic. The austerity crowd argues that government cuts will lead to more activity by the private sector. How could that be? The main way would be if the government were using so many resources that it was driving up their price and making it harder for companies to use them.

Yes. At full employment, any sector that competes for resources at market prices will drive their price up and squeeze the other sectors. The US is not even remotely at that position at present. It has millions of workers idle who can all be brought back into production if there is sufficient spending.

I often here the turn of phrase – but “there are not enough jobs” to which I typically reply – “there are plenty of jobs – a near infinity of them – just no-one willing to pay the wages for workers to perform those jobs. The US government is in a unique position that it can always afford to pay those wages and should do so by immediately announcing a Job Guarantee.

Leonhardt notes the slack in the system:

… there is no evidence that the government is gobbling up too many workers and keeping them from the private sector. When John Boehner, the speaker of the House, said last week that federal payrolls had grown by 200,000 people since Mr. Obama took office, he was simply wrong. The federal government has added only 58,000 workers, largely in national security, since January 2009. State and local governments have cut 405,000 jobs over the same span.

The claim by Boehner was wrong but also irrelevant. There are several million workers without work. By definition these workers are attracting a zero bid for their services from the private sector. The public sector can employ these workers at a living minimum wage (which at least provides income security at a reasonable standard of living) and when the private sector decides it is ready to hire again – the dynamic is simple.

Offer them an interesting job at a wage above the Job Guarantee wage and you will attract these workers out of the JG pool.

Leonhardt notes that “(w)ithout the government spending of the last two years – including tax cuts – the economy would be in vastly worse shape. Likewise, if the federal government begins laying off tens of thousands of workers now, the economy will clearly suffer.”

This is the basic macroeconomic rule – you cannot have growth in output or employment without increased spending. You do not get growth by cutting spending.

At present private spending in the US (and the UK) and almost everywhere is subdued. There is an incredible private debt overhang to eliminate as a result of the out of control credit binge (which was urged along by the very same people and ideas that are now posturing for austerity).

There is a long way to go before the private sector will have adequately restructured their balance sheets such that they will be prepared to spend freely again. Until that time economic growth will have to be driven by public spending. Cut it and you will cut growth. While I noted above that I am cautious about making predictions based on one month’s data – I am categorical about that prediction – cut spending and you cut growth.

Leonhardt says:

That’s the historical lesson of postcrisis austerity movements. The history is a rich one, too, because people understandably react to a bubble’s excesses by calling for the reverse. When Franklin Roosevelt was running for president in 1932, he repeatedly called for a balanced budget.

But no matter how morally satisfying austerity may be, it’s the wrong answer. Hoover’s austere instincts worsened the Depression. Roosevelt’s postelection reversal helped, but he also prolonged the Depression by raising taxes and cutting spending in 1937. Only the giant stimulus program known as World War II finally ended the Depression. When the private sector is hesitant to spend, the government has to – or no one will.

I like the reference to the motivation – moral satisfaction. That is ultimately what all this is coming down to – a religious crusade by zealots aided and abetted by a much more sinister motivation which is to destroy the capacity of unions to bargain for gain for their members.

And in Britain

The catastrophe that is Ireland speaks for itself. Its austerity campaign has been under way for nearly 2 years now and things keep getting worse there as any reasonable understanding of how a macroeconomic system operates would predict. There is no such thing as a expansionary fiscal contraction.

The news from Britain which is just about to really feel the chill from the austerity cuts continues to deteriorate. The UK Guardian article (February 21, 2011) – Gloom over household finances dents recovery hopes – reports that the latest “Markit household finance index fell this month to its lowest level since March 2009 as business confidence declined for the fourth consecutive quarter”.

That is not consistent with the main thrust of neo-liberal macroeconomics. The bulk of my profession try to spin the story (that is, they lie) that private sector spenders are Ricardian in nature – that is, they allege that private spending of late has been subdued because they are households and firms are so scared that the government will ramp up taxes to pay the budget deficit back.

Now that the government has announced it will be cutting discretionary net spending (which is not the same as saying that the deficit will fall), the mainstream economics prediction should have seen private spending booming by now.

The UK Guardian article says that:

Consumers and businesses are increasingly gloomy about the outlook for their own finances over the next year, leaving the government with a headache as it tries to boost confidence in the UK’s economic prospects.

The Markit household finance index fell this month to its lowest level since March 2009, while a measure of business confidence declined for the fourth consecutive quarter.

That is consistent with the view that households are scared of losing their jobs and so are trying to save and firms will not spend (invest in new productive capacity) unless they think they will be able to sell the increased production in the future. With households feely gloomy and government spending falling there is nothing that would excite private business firms. Hence their confidence is declining as well.

Further, governments do not pay back deficits!

The Survey shows that household confidence “has slumped back to the levels seen during the worst part of the recession”.

All the indicators are that real household incomes will continue to decline (see latest Bank of England Inflation Report).

Conclusion

I recommend this article in the UK Guardian (February 20, 2011) – These cuts don’t go far enough – it’s time we taxed Colin Firth’s Bafta – which concludes that:

In fact, as anyone sensible could guess, the cuts are based on emotional and ideological rather than economic concerns – in short, our politicians want us to be bloody miserable … We may have safeguarded some trees and be fighting library closures, but there are so many other areas of vulnerability left open, so many other pleasures that can be redefined in terms of monetary value and tax revenue. Every day, voters arrogantly use doorknobs without paying any kind of fee. Conversations are thoughtlessly carried on using copyrighted brand names, privately generated phrases and words that could and should be registered properly with clearly defined owners who can benefit from their regulated exploitation

A light-hearted way of saying these austerity ideologues are out of control and without the intellectual authority to wreak such damage on their nations.

That is enough for today!

“The stand out is the US which shed jobs dramatically as real GDP plummeted and as real growth has returned the recovery in the jobs market is virtually non-existing.”

So, did productivity grow along with debt (gov’t in this case)? Don’t most economists believe that productivity growth leads to higher living standards? Do any economists have a model where positive productivity growth can lead to a recession?

And, “There is a crying need for direct job creation schemes in the US to address this tendency to grow without jobs.”

Is there a crying need for more retirees and to get the medium of exchange correct?

From a time and budget perspective, is there a difference between creating more medium of exchange with “gov’t currency” and creating more medium of exchange from the demand deposits created from gov’t debt?

Bill –

I agree that cuts are a bad idea, at least in the short term. But I’ve noticed the cuts advocates are citing the USA in 1920 as proof that a nation can cut its way out of a recession.

Do you know what really happened in 1920?

Another hopeless aspect of the pro-austerity philosophy is that it never includes an explanation as to how economies recover from recessions, absent some form of stimulus.

Simple barter economies recover from recessions, or never suffer recessions in the first place because Say’s law works in simple barter economies. Keynes realised this, and gave a detailed explanation as to why he thought Say’s law didn’t work, or worked in a defective manner, in complex money based economies.

But try asking a pro-austerity economist how an economy recovers from a recession and whether it is Say’s law at work. . . . you might as well ask a chimpanzee to explain Einstein’s theory of relativity.

You say that, “The worry is that with the UK and the US already locked into a residual high unemployment as a consequence of their inadequate fiscal responses to the private spending collapse in 2008 and 2009.” My question is if the fiscal response was inadequate, or if it was misdirected from the real economy to the financial economy. I mean that if the money given to the big banks had been used to produce a real demand in the economy, wouldn’t there have been a big enough stimulus?

Also,it seems to me that even the extension of the Bush tax cuts merely directed more money to fictional capital instead of to the real productive economy. And, the irony is that most of the people in favor of the extension of the tax cuts for the rich, who will use it as fictional capital, now want spending cuts for people who would spend the money into the economy. Is that not correct?

As for a fierce political debate in Washington over spending, all we have to do look back over the past thirty years and we will know that finance and big corporations will win and the rest of us will lose, regardless of what the public thinks. I hate to be so cynical, but watching politicians has driven me to it.

GLH –

It was quite obviously both inadequate and misdirected.

Ralph Musgrave says:

Thursday, February 24, 2011 at 20:29

“Another hopeless aspect of the pro-austerity philosophy is that it never includes an explanation as to how economies recover from recessions, absent some form of stimulus.”

The neoclassical/liberal economists would argue that all unemployment is voluntary. As such, ‘incentives’ are needed to ‘encourage’ people to supply more labour. If more labour hours are supplied, the real wage will fall and output, employment will increase and changes in ‘prices’ will ensure that the extra output is sold if the incomes generated are insufficient. An example of this type of thinking is given here: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2008/12/24/are-employers-unwilling-to-hire-or-are-workers-unwilling-to-work/

For the monetarists/neo-keynesians.

The excess supply of labour {the involuntary unemployed} will lead to a fall in the money wage and, in the short run, a fall in the real wage. This will encourage more employment and output. But, since aggregate demand is unchanged, this output cannot be sold. This will lead to a fall in the price level and {assuming an exogenous supply of money} an increase in the real stock of money, a fall in interest rates and increase in wealth and an increase in aggregate demand. It is falling wages and prices that will lead to an increase in aggregate demand, output and employment.

I don’t know how the German recovery was but as the ardent mercantilist Germany usually is it’s probably not so farfetched that they surfed on others stimulus, USA showed another record trade deficit 2010 albeit not so much in GDP relative terms. Chinas record stimulus was probably another thing helping the German mercantilist.

Mercantilists is parasites and freeloaders on others stimulus’s.

Germany is also a very advanced industrial nation light-years from simple exporters of raw materials and simple menial labour intense stuff. Fewer and fewer people are needed to produce more and more. The main thing in the crises was a significant drop in the export sector, this will affect fewer jobs in Germany than in many others nations. The domestic market is sins long before the crises put on austerity to achieve export surplus. I don’t know but i suspect that’s why Germany sis seems to manage the crisis better,

In Sweden, like Germany an ardent mercantilist, it was the export sector that dropped. Last quarter of 2008 there was an immediate break on investments in the export industry, stocks was emptied out almost immediately. Investment and stocks was the major parts of GDP drop in 2009 paired with a drop in net export. But the drop in net export was almost negligible relative to GDP. Total per capita consumption dropped 2008, 2009 but that probably have more to do with the right wing gov policies than the export drop. A consumption drop despite accelerating household borrowing for consumption on their homes. The amazing thing is that our right wing finance minster first can boast his self for “strong” fiscal performance and in the next moment worry about accelerating household borrowing, he doesn’t even remotely have the ability to suspect that these two things might be connected.

Aidan says:

Thursday, February 24, 2011 at 20:23

“Bill –

I agree that cuts are a bad idea, at least in the short term. But I’ve noticed the cuts advocates are citing the USA in 1920 as proof that a nation can cut its way out of a recession.

Do you know what really happened in 1920?”

For consideration?

The country’s tariffs were raised in 1921 specifically to defend U.S. producers against the prospect of Germany and other countries depreciating their

currencies under pressure of their foreign debts. In May of that year prices began their

collapse in the United States, following the drying up of European markets that had been

supported by U.S. War and Victory loans. An emergency tariff on agricultural imports was

levied, followed in 1922 by the Fordney Tariff which restored the high level of import duties

set by the Payne-Aldrich Act of 1909. Tariffs on dutiable imports were raised to an average

38 per cent, compared to 16 per cent in 1920.

Even more devastating to international trade, the American Selling Price features of

the 1909 act were also restored as the “equalized cost of production” principle and applied it

to a number of commodity categories. This meant that tariffs were levied not according to

the value of imports as charged by foreign suppliers, but according to the value of similar

goods produced in the United States. This legislation made it virtually impossible for other

economies to undersell U.S. producers in the American market. The President was

authorized to raise tariffs wherever existing duties were insufficient to neutralize the

comparative advantage of production costs enjoyed by other countries.http://www.soilandhealth.org/03sov/0303critic/030317hudson/superimperialism.pdf

Hi Bill are the Italian taxi driver. I wanted to ask: The technology over the terrorists in the deficit will in the not too distant rising unemployment, a veritable holocaust of workers. The day that the terrorists will sconffito debt and currencies came back to us Europeans created a sovereign or sovereign European currency his theories would be able to occupy the disocuppati technology? It would be favorable to the citizen’s income? I hope the translation from Google to be understood.

Thanks for making me open my eyes to the true functioning of the monetary system

Aiden:

In 1920 the US went from a budget deficit to a surplus, which continued until 1930. Just as in the last 10 years, the surplus caused increasing private indebtedness and eventually…..1929 and history. This was one of several times that the US budget was in surplus, and each one ended in hard times. Sorry I can’t comment on your specific question of the recession and recovery of 1920-21.

Regards

John, Re the neoclassical/liberal lot, I doubt that “incentives” will “encourage’ people to supply more labour”. Reason is that people in high real wage countries (lots of “incentive” there) work much the same number of hours a week as in poorer countries.

Also you say that “incentives are needed to ‘encourage’ people to supply more labour. If more labour hours are supplied, the real wage will fall.” OK, then you “incentivise” people by paying them more in real terms. Then all of a sudden “the real wage will fall”. Sounds like a self contradiction.

However, I realise you are summarising a complicated set of ideas with very few words, so I’ll keep an eye on what the classical/neoliberal lot have to say. They might have a point.

Re the monetarists/neo-keynesians, I agree that an “increase in the real stock of money” (because of falling prices) is the route via which an economy without any artificial stimulus will escape a recession. This phenomenon is called the “Pigou effect”, and Keynes was well aware of it. But as he rightly pointed out, this effect works far too slowly because in his words “wages are sticky downwards”.

To summarise, I’m still waiting for an explanation from the pro-austerity lot as to how economies recover of their own accord from recessions.

For Aiden @20:23,

Someone at a loss for a logical reason can always find some situation no-one knows about and cite it as an example. Once you debunk that, they’ll find another to cite. It’s an unending moving target.

Within the last year Canada’s period of austerity in the early 1990s was widely cited as an example for others, the UK in particular. It was nonsense. The Canadian federal government did cut back then but the US economy began a boom and a big increase in Canada’s exports allowed the country to escape without great hardship. The cutbacks to barely adequate social programs (health care, unemployment insurance, welfare) remain to this day and cause considerable hardship. Unless the UK can produce a very large increase in net exports the recommendation is nonsense.

Bill – apologies if I’ve missed this, but do you have a simple Excel model on your site which relates GDP growth to the financial balances? I have seen one which is xla but I can’t convert it – xls would be great if possible.

Many thanks

About the early 1920’s, where were price inflation and interest rates then?

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Depression_of_1920-21

From Aiden’s link:

“Rates were sharply reduced in the latter half of 1921. The New York Federal Reserve reduced rates in successive half-point moves over the July- November period from the 7% high to 4.5% on November 3 1921. The depression ended.”

I doubt if that got savers to spend that much more, although that is possbile. What happened to the dollar, net exports, gov’t debt levels, and probably most importantly private debt levels?

Should be from Aidan’s link.

I think you can sum up the austerity (Austrian?) argument rather simply;

Government cuts spending and increases taxes

????

Profit!

I think it is very important to be careful when considering GDP. It often does not relate to affluence or people having the jobs they want. Much of the GDP in Ireland and the UK in the lead up to the crisis was just frenetic buying and selling of buildings. Of itself that economic activity was counterproductive. Even if a policy does boost GDP, it is important to question whether it will have a genuine benefit. Aiming purely for rising GDP is like a vet aiming purely for a dog to have a wet nose as a measure of good health and acting by putting water on the sick dog’s nose to turn it from dry to wet.

“So it is more about their unwillingness to let go of what are essentially religious beliefs that leads the mainstream economists to constantly pump out rubbish and lie when they are found out (by the facts)”

What we are dealing with here, I think, is a phenomenon of racist lies. Understanding economy is hard, so only people motivated enough to come out and claim they understand the system are those motivated by racist hate against “the other kind”. Majority of the people just don’t think themselves and too easily believe someone who just claims something. In absence of clear thinking and good, realistic theories, economic profession just becomes mindless repeater of racist lies designed to deprivate ordinary people’s livelihoods.