I have received several E-mails over the last few weeks that suggest that the economics…

So near but so far … from comprehension

I have very little time again today so to the point! Sometimes you are reading an article or column and you nod along saying – yeh, that is correct, this writer understands it … and then crunch … the brick wall appears – one word, one phrase, one sentence, one paragraph and all that bonhomie evaporates and you realise that the writer isn’t as cognisant of the way the macroeconomy works as you first thought. It is a case of so near but so far.

Such was my experience early this morning when I read the latest Financial Times article (March 15, 2011) by Martin Wolf – Japan can meet the earthquake test.

Wolf is writing about the ability of the Japanese people to meet the monumental challenge that they now face to restore a sense of stability to their communities and then seek renewed prosperity.

He concluded that the Japanese people have demonstrated their considerable mettle in the past and he hoped their leaders were capable of stepping up to the plate to match their resilience and sense of purpose.

Wolf wrote:

If any civilisation is inured to such tragedies it is Japan’s. Its people will cope. This seems certain. A bigger question is whether something more positive might emerge from the tragedy. Japan’s bickering politicians are on trial. Can they sustain the mood of national unity? If so will they use it to take Japan out of the doldrums of the past two decades?

I agree with most of this. The Japanese people have been beset by considerable anguish in the past (and delivered considerable anguish on others too don’t forget).

The problem is that their government is pretty much incapable of dealing with the economy as they flee into conservatism. All the talk of putting taxes up to “pay for” the reconstruction effort is beyond belief.

Wolf also attacked the notion that is now circulating that Japan cannot afford to meet the fiscal challenge presented by the devastating natural disaster.

Please read my blog – Earthquake lies – for more discussion on this point.

Wolf assesses the damage of the disaster as being less in:

… magnitude as that of the global financial crisis. That drove down Japan’s GDP by 10 per cent between the first quarters of 2008 and 2009, the steepest decline in the Group of Seven leading high-income countries. The impact of this shock will certainly be far smaller.

Given that the reconstruction will add to GDP growth (via public investment) this is probably a reasonable assessment although doesn’t have any bearing on the Japanese government’s capacity to meet its spending obligations in terms of an appropriate reconstruction.

In terms of the fiscal position, Wolf said that once you consider the likely impact on revenues and outlays:

… these sums are too small to have any meaningful bearing on fiscal solvency.

I agree that the sums involved will be rather small in relative terms but at this point Wolf was losing me. The implication of his assessment is that the Japanese government does have a solvency risk but not just yet at this scale of deficit.

The reality is that the Japanese government has no solvency risk at all in relation to its net spending position and the debt issuance that matches it (nearly). It is grossly misleading to leave the impression that it is just because the reconstruction sums are small that their is no insolvency risk.

Then the wheels fell off.

He considers the point that the deficit terrorists (most mainstream economists) are raising as to:

… whether Japan’s government can afford additional spending.

His immediate conclusion is that these commentators “need not do so” – that is, should not be concerned. I agree entirely. The fact they are concerned demonstrates that they do not understand the way the fiscal policy dynamics work within a fiat monetary system.

The national government of Japan can always afford to purchase concrete, wood, steel, glass, health care, road contractors etc as long as those resources are available for sale in Yen.

There is no question about that. It issues the currency as a monopoly provider (that is, as a consolidated treasury/central bank unit). It doesn’t make any sense to say that the issuer of the currency can be constrained in terms of using that currency.

Intrinsically that cannot be the case. Politically, it is a different matter and the politicians might attempt to put themselves in a straitjacket and pretend that they have to spend on a quantity rule – which means that they set some budget deficit limit and allocated funds to that limit.

But the imposition of such constraints would not be based on anything operational or intrinsic in relation to the characteristics of the monetary system the government oversees. It would be short-sighted and damaging conservatism – an act of vandalism such that we saw in 1997 when the deficit terrorists held political sway and successfully pressured the Japanese government to tighten fiscal policy.

The 1997 GDP plunge – just as the economy was beginning to recover from the property crash in the early 1990s – followed this stupidity. Fortunately the government realised this mistake and started supporting growth again from 1998 onwards and by the time the financial crisis hit the economy was starting to look to be in better shape.

Wolf, however, has a different view on affordability and it is here that you have to be attune to the detail to understand why this next tract gives the game away totally (if the previously comments on insolvency hadn’t already achieved that end):

Japan can and unquestionably will pay these relatively modest sums. The Japanese private sector runs a financial surplus large enough to cover the government’s deficit and export substantial capital abroad. Japan as a whole is the world’s largest creditor, with net external assets equal to 60 per cent of GDP. In short, the assets of Japan’s private sector vastly exceed the liabilities of its public sector.

The government’s debt is a way for the Japanese to owe money to themselves. At some point, no doubt, that debt will turn into taxation, either overt or covert (the latter via inflation and reductions in the value of Japanese government debt). Since total government receipts are still only 33 per cent of GDP, raising taxes should really not be so hard. The idea that the government confronts an imminent fiscal crisis strikes me as quite bizarre.

Correct conclusion – “The idea that the government confronts an imminent fiscal crisis strikes me as quite bizarre”. Total ignorance leads to conclusions that there will be a fiscal crisis.

Terrible justification though. Others have noticed this point as well (cheers Rob in SF). I will return to this in a moment.

Some theory

Before we consider the problem I have with Wolf’s reasoning we need some theory.

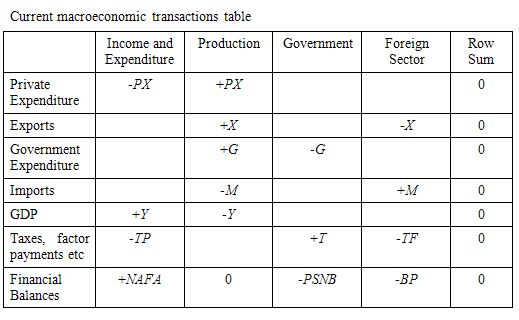

Consider the following table which is a macroeconomic transactions table which, in this case, simplifies the components of GDP. Here, Gross Domestic Product, Y, is equal to Private expenditure, PX, plus government expenditure, G, plus exports, X, minus imports, M.

The external – Rest of World (ROW) account – reveals that imports minus exports and transfers paid by the external sector, TF, equals the balance of payments deficit.

Every item in the Production (GDP) account is matched by a corresponding negative entry in some other column.

Taxes net of transfers are received by the government. Net property income, taxes and transfers, TF and TP, are paid by the external and private sectors, respectively.

The final row totals reveal that public sector net borrowing, PSNB, equals the private net acquisition of financial assets, NAFA (private savings less investment) minus the balance of payments surplus (or plus the deficit), BP.

You can read more about these tables in a working paper I wrote with a colleague in 2008 – available HERE. The paper was subsequently published but this version is close enough to the final version and is free to access.

Please read my blog – Stock-flow consistent macro models – for more discussion on this point.

From the perspective of a stock-flow consistent approach to macroeconomic modelling, the fundamental accounting identity states that government savings (surplus) or tax revenue net of government spending and payment of interest on bonds is equal to the non-government sector’s dis-saving.

This is inescapable and an artefact of the way the National Accounts are constructed. It is not my opinion or a matter of interpretation.

So public sector net borrowing equals the private net acquisition of financial assets (private savings less investment) minus the balance of payments surplus (or plus the deficit).

As governments moved away from deficit spending at levels typical of the post-war period of full-employment, private sector debt levels have escalated. This is one of the defining characteristics of the neo-liberal period.

The reason why this has happened is that causality flows from fiscal policy to the private sector simply because economic influences over the rest-of-the-world account change quite slowly, with income effects dominating over the price effects that are championed by mainstream macroeconomists.

In contrast, fiscal policy responds immediately to government decisions about spending and taxing. The transmission mechanism behind these changes is complex, as it operates within a portfolio setting, by changing relative rates-of-return between real investment, the equity-premium, and the term structure of bonds.

Japan, as we will see, has experienced slightly different trends than other advanced nations because it has a strong net exports sector, is culturally attuned to higher private domestic saving ratios, and suffered its property crash some two decades before everyone else.

The bottom row in the current transactions table sums to zero and is just another way of expressing the sectoral balances that I have written about often.

Please read my blogs – Barnaby, better to walk before we run – Stock-flow consistent macro models – Norway and sectoral balances – The OECD is at it again! – for more discussion on this point.

The bottom row can be re-written in more familiar terms – the accounting identity for the three sectoral balances:

(S – I) = (G – T) + (X – M)

This says in English that total private domestic savings (S) is equal to private domestic investment (I) plus the public deficit (spending, G minus taxes, T) plus net exports (exports (X) minus imports (M)), where net exports represent the net savings of non-residents.

Thus, when an external deficit (X – M < 0) and public surplus (G - T < 0) coincide, there must be a private deficit. While private spending can persist for a time under these conditions using the net savings of the external sector, the private sector becomes increasingly indebted in the process.

When there is an external surplus, the public (budget) balance may be in surplus while still permitting the private domestic sector to save. This is the Norwegian situation.

But when private savings desires are strong (and overwhelm the external surplus) as in Japan, then you have to have a public (budget) deficit to support growth.

I will come back to that point soon after considering the sectoral balances for Japan.

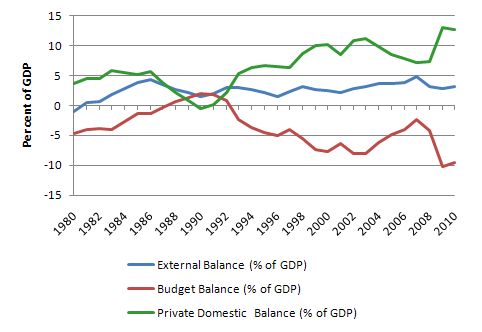

The following graph shows the sectoral balances for Japan from 1980 to 2010 (using IMF WEO data).

You can see that there is a fairly stable external surplus arising from trade in Japan although it certainly took a hit in the recent downturn.

In that context, you will also observe that the private sector surplus has increased steadily since the early 1990s with some fluctuations. The growth in private net saving has been in line with the long term increase in budget deficits.

The public balance has been in deficit (and rising) since the property crash in the early 1990s.

In line with our previous (causal) understanding, the persistent and substantial fiscal deficits have “financed” the saving desires of the private sector and helped to maintain positive levels of real activity in the economy. These relationships demonstrate the strength of fiscal policy to underwrite economic activity.

The way this works is simple but not well understood (and totally misrepresented by the neo-liberals and Wolf).

Economic growth – in terms of income and output – that is, GDP growth – requires growth in aggregate demand (spending). If one of the aggregate spending components noted above falls – for example, the private domestic sector increases its desire to net save and implements that desire by cutting back on consumption and/or investment – then for economic growth to continue at its current rate one of the other sectors has to come to the party.

So a rise in net exports could maintain growth and/or a rise in net public spending (that is, a rising budget deficit).

If net exports are relatively steady, then a fall in private spending overall has to be met with a rise in net public spending if growth is to be maintained.

The ability of the private domestic sector to save is also dependent on the level of income. If income rises, saving rises and vice versa. So if the government doesn’t come to the party and boost spending when private spending falls, income will fall but so will private saving.

Once you understand that basic macroeconomic dynamic then you will easily be able understand that it is the rising budget deficits which are driving income growth in Japan and thus “financing” the desire of the private sector to save.

Wolf – gets this wrong

Wolf, however, gets this causality wrong.

Wolf has been introducing the sectoral balances into his analysis increasingly over the last few years. The only problem is that you have to interpret them and use them with some basic prior understandings.

Yes, the private domestic sector in Japan does run a huge financial surplus – it spends less than it earns by far. There are various reasons for this – some cultural – some institutional (which might be reflect culture) – but it is a reality.

Yes, the external sector runs a surplus too which adds to growth in net terms. Net exports took a beating in downturn but are showing signs of recovery.

But the conclusion that the government will be able to afford the reconstruction effort because the “Japanese private sector runs a financial surplus large enough to cover the government’s deficit” is incorrect.

It implies that the deficit draws on past private saving and requires that saving for funding. That is misinformation.

Reflect back on the previous discussion about the way in which budget deficits “finance” private saving desires and maintain income growth consistent with those desires. Understanding that point should lead you to conclude that without the deficits there would be no realisation of the private saving desire (for a constant external position) because aggregate demand would falter and income growth would fall.

The reality is that net government spending provides the funds that are borrowed back. The borrowing is totally unnecessary for the government to spend. It is totally sovereign in its own currency.

That is the reason that the Japanese government will be able to “afford” to reconstruct its northern regions (subject to real resource availability). It has nothing at all to do with the private surpluses. They will fall if the deficit was cut.

The Japanese economy beguiles analysts who attempt to apply orthodox macroeconomic theory to its aggregates. It is clear that Japan has had the highest public debt ever recorded and faced repeated downgrades from the ratings agencies. It has also run persistently large fiscal deficits for more than 20 years.

Every day the Bank of Japan issues as many treasury bills as it likes at virtually zero interest yields. Further, inflation has been low and sometimes negative since 1991. So if deficits really caused high interest rates and/or runaway inflation, Japan would have revealed these pathologies years ago.

The fact is the Bank of Japan does not completely drain the “fiscal wash” every day with its treasury bill issue and in this way allows competition between the commercial member banks to keep the short-term interest rate at around zero.

This, in turn, allows the longer rates to be as low as possible and provide a favourable climate for investment. In turn, the fiscal stimulus is designed to counteract the deflationary impacts of the private saving.

I also dispute the Ricardian overtones that the “debt will turn into taxation, either overt or covert”. It might if the politicians are stupid. But there is no financial necessity for it to do so.

Tax rates might rise in the future but that would only reflect the need to slow private demand to prevent inflation from occuring. They are so far from that situation at present.

Please read my earlier blogs – Balance sheet recessions and democracy and Japan – up against the neo-liberal machine – for further discussion on Japan.

Conclusion

So I agree with Wolf’s conclusion that:

The idea that the government confronts an imminent fiscal crisis strikes me as quite bizarre.

I just wish he had have explained that conclusion in a better way without all the mis-information which really plays into the hands of the mainstream.

That is enough for today!

This is a constant problem – people get the answer correct, but with the wrong (sometimes completely wrong) working.

“It implies that the deficit draws on past private saving and requires that saving for funding. That is misinformation”

I’ve been hearing that a lot. There seems to be a desire to represent the government spending in terms of some sort of Net Present Value calculation.

However the mathematics don’t work when you talk about period zero (ie the point at which a fiat currency is created). If government spending has to be prior funded then a fiat currency can never get going. In period zero there is nothing to borrow and no prior taxes.

And the solution appears to assume period zero away. I’m presuming this is the exogenous vs. endogenous debate writ large.

When you ask a classical economist to explain period zero they tend to get agitated. They always want to start half a cycle down the road.

It seems to me that the entire descriptive power of the MMT model is determined in that period zero debate. The currency issuer *has* to provide the currency to others first. Therefore it has to impose a demand for it – hence taxation.

Has anybody studied the Brazilian Real switchover (or another recent new fiat system) from an MMT point of view to see how that was introduced. It’d be interesting to see if that currency followed the predicted process.

An interesting article in the Guardian today.

Putting aside the reference at the end to Japan being “awash with debt”, I find it interesting that a model should show that Japan booms immediately after massive inward investment, and presumably increasing the deficit. Any comments?

My understanding, corrections welcome, is that today’s fiat currencies can be traced back to commodity money. Money was originally a commodity, then paper money was linked to it, and then the paper-commodity link was gradually weakened. At no time did governments face the challenge of creating a demand from scratch.

“The reality is that net government spending provides the funds that are borrowed back.”

This is true of net spending from any sector – the money created by banking arrangements can be left as, is or “borrowed back” (i.e. effectively withdrawn from the banking system.)

Max, I thought that British colonialists did create fiat currency from scratch in West Africa. They levied a hut tax that had to be paid in the newly created currency and said that the novel currency could be obtained by working for the colonialists or by selling things to people who had been paid by the colonialists etc etc.

Max,

You seem to be referring to Mises regression theory. Unfortunately, there is not a crumb of empirical evidence to support any of it.

Tax driven money is where the truth resides, and the example provided by Stone above is a very good one.

Cheers.

Max,

This is a paper from 2005 that might help your investigations. in a roundabout way.

http://174.143.107.17/wp-content/graphs/2009/07/natural-rate-is-zero.PDF

Cheers

Neil someone posted at Warren’s blog a link to a NPR program about money where they discussed the (latest) brazilian introduction of a new currency, the real. I didn’t keep it, but maybe you can google it, it was quite interesting. Many countries did similar things to get rid of hyperinflation by creating a new currency that people would trust. If I recall correctly they did it in two steps. First they created a virtual currency that will float against their local one, to anchor prices in the virtual currency, and then introduced the real at par with the virtual currency. All in all it is a kind of peg or currency which is the standard solution to stop runaway inflation.

So most fiat currencies have replaced commodity or other fiat currencies, the period 0 always start with the private sector already holding financial assets in the old currency which are then converted to the new one.

I would like to read more about the creation of a fiat currency from scratch in west africa. Did they have their own currency before or was it a barter economy?

Max,

There was a misconception that money was ever a commodity that goes on to this day. Unless they are trading nails, cigarettes or something like this it is not commodity money but barter, one asset for another. Commodities are an asset only with no corresponding liability for anyone, this is different from money which is also a liability to someone, so by definition debt. If you notice the coins of ancient time had a stamp on them to give them numeric value above their commodity value. If the commodity price would ever rise above the face value, those coins would be melted down and sold for a profit.

I don’t understand why investment I subtracts from the private sector balance. If savings S are 90 and investment is 100, the balance in this formulation is negative, but the private sector still has positive savings and ample investment. Why does MMT say in such situation that the balance “deteriorates”?

MamMoTh, there are lots of links from the wikipaedia entry for hut tax. Its was a classic colonialist tool used by the Germans in Namibia and by the British throughout Africa. I guess the people subjected to it varied from those using pure barter to those with established use of money for long range trading and also intermediate cases with use of cowerie shells etc as an informal medium of exchange.

To me the hut tax money is much less startling than that Austrian empire money was in use in Africa by people with no link to the Austrian empire decades after the Austrian empire was defunct and no one in europe would accept it as money. That is money trading as pure convention. I guess the monetary value of precious metals is no more hard to understand from a logical point of view though.

stone, thanks, i will look it up. it’s interesting what you say, so there is evidence for a tax-driven currency by means of a tax hut, and for a non tax-driven currency used by pure convention. I wonder how relevant the concept of tax-driven money is to MMT. It doesn’t seem to be necessary at all to me.

Max,

Historically, there has commonly been long periods where trading systems that were not under one sovereignty had both local monies and international trading moneys.

Local moneys are always based on “sovereign currency”, aka vertical money, in which tax obligations may be met. That is why the unit of currency in so many places is either a unit of weight, or a unit of land, since the dominant early tax obligations were an amount of staple crop per unit of land. “pound” “dolar” “peso” “yen”.

Sometimes international moneys have been the local money if either a dominant economy or a country with a currency that otherwise holds its value well, sometimes it has been a commodity convertible into various local moneys, such as gold and silver under the medieval monetary system of private mints franchised by the monarch.

But there is no strong historical evidence for the emergence of commodity money first and then its adoption by sovereigns. The historical evidence both in the Med and in East Asia, points to money being an innovation by temple/warlord governments who previously had to satisfy all of their material needs by direct requisition.

The common method for fabricating a “Just So” story for international money is to start in Medieval Europe, in which private mints were chartered by local kings to mint coin containing a given quantity of previous metal, collecting brassage to cover their operating costs (and profits) and seigniorage as a tax to pay to the king that granted the charter. But this ignores the fact that Medieval Europe had already been exposed to a monetary economy under Rome, and the royal mints were a means of providing for a monetary system by governments that did not have the Roman capacity to mint their own coinage.

Push back from the royal mints, in other words, and you do NOT find circulating silver and gold as “exchange commodities” ~ instead you find money issued directly by the state, following existing practice in the Mediterranean trading system. Ditto in East Asia ~ push back to the earliest archeological evidence, and the coins are issued by government.

Bruce – These are important points you raise against the simple goldsmith/commodity money stories that have been handed down by the mainstream regarding the origin and history of money. Would you be able to recommend some links or published articles or books that might take us further into some of the points you made in the above comment?

Peter

The way that I understand Investment is that if you buy a house or build a factory you decrease your savings and increase your investment. Investment if well done can increase your savings in the future since it can yield income unless the investment does not yield anything useful such as either rent on the house or have the factory build something useful. It seems to me that building houses that could not provide rents was a big part of the collapse of the economy that we saw.

Please anybody correct me if you feel this is wrong, since I am trying to better understand what investment is myself.

Best regards

Speaking of money getting started…I wonder if anyone here is monitoring ‘bitcoin’ (a digital money) developments. It’s not clear to me how or if such a money can be popularized. Nevertheless it’s an interesting bit of technology.

sidchem, no, your investment is someone else’s income, so investment creates savings.

the way i see it, S-I<0 means that not all the invested money could be saved by the private

sector because they leaked to the foreign or government sector.

what i would like to know is why is I considered coming from the private domestic sector

and not from the foreign sector as well.

There was a misconception that money was ever a commodity that goes on to this day.

“Commodity money” by definition involves barter. Modern money is credit-based.

See L. Randall Wary, “Money,” Working Paper 647, Levy (2010), and “The Origins of Money and the Development of the Modem Financial System,” Working Paper 86, Levy (1993).

Sidhem,

I think if you have spare 120 units of money, you can save 30 and invest 90, but what subtracting one from another 30-90 would mean is totally unclear to me.

In aggregates S-I is the savings in the system above the total system-wide investment, I don’t understand the significance of this quantity, or why would call it a surplus if positive.

Maybe S-I means that these are the assets that are stored in financial form. Investment is owning a house, factory or a piece of machinery, so S-I would be the savings in the system that are not met by physical investment assets, and are thus stored in terms of financial assets (dollars, bonds etc).

Income = Expenditure (“spending’)

Y (income) = C (consumer spending) + I (firm spending) + G (government spending) + (X-M) (spending by ROW)

ROW = “rest of the world,” i.e., foreigners. X (exports)-M (imports) = net spending by foreigners.

Several of the entries for the BBC Radio4 series (is on the web with pictures) “history of the world in 100 objects” are sorts of money. They have chopped silver from Vikings (a reversion to/adoption of commodity money when other cultures were using coins); the first paper money from china; the first gold coins and the Spanish silver “pieces of eight” that they said were used as an international global money for hundreds of years -even in Austrialia hundreds of years after they were minted. The program claimed that the Ancient Egyptians used gold and silver by weight as commodity money and that predated any known coins.

With regard to MamMoTh’s idea that tax isn’t required for fiat money- there is a chicken and egg situation with getting a convention underway. Money is potentially the purest form speculation- you accept it in the hope that someone subsequently will accept it from you. That is the only value it has. Precious metal “commodity money” has a small part of its value due to decorative or industrial use but it is only a small part. When silver stopped having a monetary role its value relative to everything else plummeted. Cowerie shells presumably have a small decorative value but in effect were probably purely a convention driven fiat money. I think people used them without anyone demanding tax paid with them. Tax such as a hut tax is a sure fire way to assert a fiat currency straight off. I guess a “legal tender” law might be an alternative sure fire method.

Bruce,

Perhaps to your point, why would someone go to the trouble of striking a counterfeit denarius out of silver, if it was the metallic content that imbued value?

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-1326292/The-Roman-Del-Boy-Cleaner-finds-ancient-fake-coin-Egypt-spelled-wrong.html

This to me is empirical evidence that it was the coercive force of taxes (in this case the Roman Poll Tax) , payable only in the coins spent into circulation by the sovereign for provisioning the government, that has always been the source of currency value.

Resp,

Dear Peter (at 2011/03/17 at 1:30)

You said:

The answer is to understand that we are talking macroeconomics here – aggregates and the sectoral balances apply to the net position overall. Sure enough in your example, some people will be saving but overall the sector is in deficit and accumulating debt or running down assets.

That is the way to understand your dilemma.

best wishes

bill

“When silver stopped having a monetary role its value relative to everything else plummeted.”

On the other hand, look at gold since 1971. Being officially de-monetized was good for gold. This was contrary to some predictions (e.g. by Milton Friedman) at the time.

In S-I, can someone define I for me?

Specifically, can someone “I” (invest) in currency only, demand deposits only, financial assets, and goods/services?

Can someone define savings for me?

Thanks!

Love your work Bill. You’ve certainly opened my mind since I began intermittently reading your blog about a year ago. Last week I cancelled my FT subscription after coming to the realisation that its journos would never dare question the dogma of the cult of Friedman and the usual suspects. In the past Martin sometimes gave the impression that he understood that neoclassicism is a load of guff. I suspect that he is on notice from his corporate masters that no head-on criticism of this pernicious school will be tolerated, only indirect (between the lines) sniping. This brings to mind the statement by Warren Mosler that the senators from Connecticut have read, and understand, Mosler’s book yet continue to publicly pay homage to idea that Uncle Sam faces a solvency constraint.

On another matter, given that interest rates are such a blunt instrument for managing aggregate demand (there are retirees who live off bank interest, yet there are also mortgage and business borrowers) would you be in favour of a fiscal authority tasked with varying the tax rates levied on different sectors on a continuous basis to maintain full employment?

All the best mate

@Fed Up

The precise definition depends on which accounting system you use, but it is generally speaking it is the creation of wealth. What constitutes wealth differs, from say how the national accounts do it vs GAAP, but generally speaking it is things like plant, equipment and inventory. The creation of wealth is called investment. The accumulation of wealth is called saving. Logically the two must be equal.

Dear Fed Up (at 2011/03/17 at 12:06)

In the National Accounting system S and I have very precise meanings. S is disposable income not consumed. I is gross fixed capital formation (that is, creation of productive capacity – machines, equipments, buildings etc) plus inventory variations.

Investment in this accounting framework does not mean buying financial assets which is the usage that is common in normal discourse.

best wishes

bill

“I is gross fixed capital formation (that is, creation of productive capacity – machines, equipments, buildings etc) plus inventory variations.”

You all might be amused to learn that staff training and education does not form part of I.

Staff Training and Education appears to be classified as consumption in the national accounting system – which in strict accounting terms is correct since you can’t really sell it on again.

However from an economic perspective, manipulating ‘I’ without adjusting for education (and other hidden investment erroneously classified as consumption) seems a bit odd as you will always underestimate the productive capacity of the economy.

(Note that ‘I’ being inaccurate doesn’t alter the value of ‘S – I’ since ‘S’ would automatically follow any adjustment in ‘I’)

“I is gross fixed capital formation (that is, creation of productive capacity – machines, equipments, buildings etc) plus inventory variations.”

That is an amazing definition. Does creation of patented inventions not count. An FDA approved drug as “intellectual property” could be sold on for billions of dollars. Does that really not count as investment. What about a “brand”. CocaCola’s brand image presumably is worth more than all of their machines, equipments, buildings etc.

There is a category called ‘Investment in Knowledge’ which is described as “Investment in this context has a broader connotation than its usual meaning in economic statistics. It includes current expenditures, such as on education and R&D, as well as capital outlays, such as purchases of software and construction of school buildings.”

Fixed Capital Formation include traditional intellectual property rights (ie something that can be owned, independently valued and traded), so that would include brands, drugs, artworks, etc.

Neil Wilson, thanks for the clarification but it does seem hard to equate such a woolly situation with what Bill calls “very precise meanings”. So with say Manchester United Football Club, the players’ contracts would be Fixed Capital Formation and so investment. Presumably the value of the youth team as manifested in the share price would also count as investment. I find it hard to draw a line between that and staff training. Presumably a “rational” company would not conduct staff training if it did not pay for its self in terms of being manifested as monetary value for the owners of the company.

Thanks Tschäff & bill!

If rich people and rich corporations save in currency, save in demand deposits, or save in financial assets because they don’t need/want to spend more, there is enough of most products so they don’t invest more, and don’t/won’t retire, can that lead to economic problems if the financial assets don’t go down in value and the demand deposits don’t go down in value?

https://billmitchell.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/Japan_sectoral_balances_1980_2010.jpg

In that graph, shouldn’t the blue line be negated? That is, there are only two degrees of freedom because the variables are not independent, yet the graph obscures that fact. Inverting the blue line (external balance) would be clearer, no?

Min.

Thursday, March 24, 2011 at 4:03

“In that graph, shouldn’t the blue line be negated?…”

I’d rather advise to redraw the graph, in order to have CAB positive (if surplus), BB positive (if deficit) and PDB negative (if surplus).

Regard.