I have received several E-mails over the last few weeks that suggest that the economics…

Martin Feldstein should be ignored

I am still away from my office and have had a full-day of meetings today – so very little time to write. But earlier today I read another one of those articles from a senior US academic economist about the need to cut aged pensions in the US because the government is running out of money. Martin Feldstein – a Harvard professor – has been found to have engaged in highly questionable conduct (to say the least) by investigations into the causes of the financial crisis. Feldstein must surely know that the government cannot run out of money. Which brings into question his motivation for providing misleading interventions into the policy debate. He has demonstrated over a long period his willingness to hide behind the “authority” of economic theory in order to pursue an ideological obsession with privatisation and deregulation. When writing what seemed to be academic papers or opinion pieces supporting financial deregulation, for example, he didn’t at the same time declare that he was personally gaining from such a policy push. His subsequent track record as a board member of companies, some of which collapsed in the crisis (AIG) or triggered the collapse has been appalling. Feldstein is not the sort of person anyone should take advice from much less pay for it.

I read the statement made by the President of the US yesterday where he said:

The cause of securing our country is not complete. But tonight, we are once again reminded that America can do whatever we set our mind to. That is the story of our history, whether it’s the pursuit of prosperity for our people, or the struggle for equality for all our citizens; our commitment to stand up for our values abroad, and our sacrifices to make the world a safer place.

I thought – yes America can do whatever it sets it mind to – except create enough jobs to ensure that families have secure incomes and children have a secure future. That relatively simple task seems to escape them. But then I thought about the wording more carefully and “whatever we set our mind to” became the focus.

There are millions of Americans unemployed including nearly one-quarter of 16-19 years old who desire to work – and the American government clearly “hasn’t set its mind to” providing them with opportunities to work.

The world is certainly not a safer place for the unemployed.

It comes as no surprise though given the type of economist that provides the US government with advice – Summers, Rubin, etc – a long line of deregulating, in-it-for-themselves advisers. On February 9, 2009 Harvard professor joined a long line of such characters accepting official appointments. He was appointed to the US President’s Economic Recovery Advisory Board which was formed top advise him on appropriate remedies to the crisis.

Feldstein would have been one of the last people I would have appointed to such a role given his background. You only have to read this Wall Street Journal article (May 2, 2011) – Private Accounts Can Save Social Security – where Feldstein advocates cutting public pensions for the aged because the US government cannot afford to pay such entitlements. He promotes the privatisation of the pension scheme.

By way of background, Feldstein was one of the economists named in the recent investigative movie – Inside Job – which the Director Charles Ferguson said was about “the systemic corruption of the United States by the financial services industry and the consequences of that systemic corruption.”

Feldstein ran the Boston-based private organisation National Bureau of Economic Research for nearly 3 decades. The NBER provides an avenue for the mainstream economists to build national prestige and a range of influential appointments. If you examine the research and publication agenda of the NBER you will appreciate that under Feldstein’s direction various mainstream economic policies were promoted – including his Wall Street Journal topic – privatising the US pension and the health systems.

They also pushed economic analysis claiming to justify the optimality of deregulating the financial sector.

Charles Ferguson wrote in The Chronicle Review (Chronicle of Higher Education):

Martin Feldstein, a Harvard professor, a major architect of deregulation in the Reagan administration, president for 30 years of the National Bureau of Economic Research, and for 20 years on the boards of directors of both AIG, which paid him more than $6-million, and AIG Financial Products, whose derivatives deals destroyed the company. Feldstein has written several hundred papers, on many subjects; none of them address the dangers of unregulated financial derivatives or financial-industry compensation.

For those who haven’t seen the movie, here is a transcript of the segments with Feldstein. Arrogance understates his contribution to the movie.

Ferguson: Over the last decade, the financial services industry has made about 5 billion dollars’ worth of political contributions in the United States. Um; that’s kind of a lot of money.That doesn’t bother you?

Feldstein: No.

Narrator: Martin Feldstein is a professor at Harvard, and one of the world’s most prominent economists. As President Reagan’s chief economic advisor, he was a major architect of deregulation. And from 1988 until 2009, he was on the board of directors of both AIG and AIG Financial Products, which paid him millions of dollars.

Ferguson: You have any regrets about having been on AIG’s board?

Feldstein: I have no comments. No, I have no regrets about being on AIG’s board.

Ferguson: None.

Feldstein: That I can s-, absolutely none. Absolutely none.

Ferguson: Okay. Um – you have any regrets about, uh, AIG’s decisions?

Feldstein: I cannot say anything more about AIG

Later in the movie Ferguson re-engages with Feldstein:

Ferguson: You’ve written a very large number of articles, about a very wide array of subjects. You never saw fit to investigate the risks of unregulated credit default swaps?

Feldstein: I never did.

Ferguson: Same question with regard to executive compensation; uh, the regulation of corporate governance; the effect of political contributions –

Feldstein: What, uh, what, uh, w-, I don’t know that I would have anything to add to those discussions.

Feldstein is not the sort of person anyone should take advice from much less pay for it.

In his Wall Street Journal article he exercised all the mainstream myths about pensions and claimed that “(e)ven Mr. Obama accepts the inevitability of lower future Social Security benefits”. Which doesn’t sit well with his speech yesterday which claimed that America was about “the pursuit of prosperity for our people”.

Feldstein claims that the American pension system is collapsing because the dependency ratio is rising or in his words:

There are now three employees paying Social Security taxes to finance the benefit of each retiree. That number will fall over the next three decades to only two employees per retiree. This would require either a 50% rise in the Social Security tax rate to maintain the existing benefit rules, or a one-third cut in projected benefits to maintain the existing tax rate.

The correct statement is that the employees produce real goods and services which define the material standard of living for those who do not produce real goods and services (but may have in the past). The taxpayers only look as if they finance social security in the US because of the accounting arrangements that are in place to account for the tax receipts.

The reality is that the public pension scheme does not require any funding at all – as a branch of government it can always pay the pensions as long as they are denominated in US dollars.

So Feldstein is lying by claiming that tax rates have to rise or benefits fall. Neither is required when you understand the intrinsic financial issues involved.

So his claim that “(t)hat’s why every serious budget analysis calls for reducing the growth of Social Security benefits” is spurious and just rehearses his regular calls to private social security and deregulate markets in general. He has no credibility at all on this position.

A serious budget analysis would suggest that health care costs are rising because the American government is too scared to introduce a competitive insurance scheme and the private insurance industry has excessive market power. In making that statement I am not acknowledging that there is a budget blowout issue. It is merely a reflection that Americans spend more on health per capita than anyone and are among the least healthy. Something is wrong and it is not an impending budget collapse.

All the tinkering with the US pension scheme such as that proposed by (as Feldstein says) “(t)he bipartisan Simpson-Bowles Fiscal Commission appointed by President Barack Obama” – like “slowing the rise in Social Security benefits by increasing the age at which full benefits would be payable, and by changing the benefit formula so that the ratio of benefits to previous wages gradually declines for most future retirees” – completely misrepresent the true nature of the problem facing a nation with a rising dependency ratio.

Feldstein chooses to perpetuate that ignorance presumably because he senses some personal gain in do so – given his track record that was exposed in the Inside Job.

What is the problem with a rising dependency ratio?

First of all, what is a dependency ratio?

The standard dependency ratio is normally defined as 100*(population 0-15 years) + (population over 65 years) all divided by the (population between 15-64 years). Historically, people retired after 64 years and so this was considered reasonable. The working age population (15-64 year olds) then were seen to be supporting the young and the old.

The aged dependency ratio is calculated as:

100*Number of persons over 65 years of age divided by the number of persons of working age (15-65 years).

The child dependency ratio is calculated as:

100*Number of persons under 15 years of age divided by the number of persons of working age (15-65 years).

The total dependency ratio is the sum of the two. You can clearly manipulate the “retirement age” and add workers older than 65 into the denominator and subtract them from the numerator.

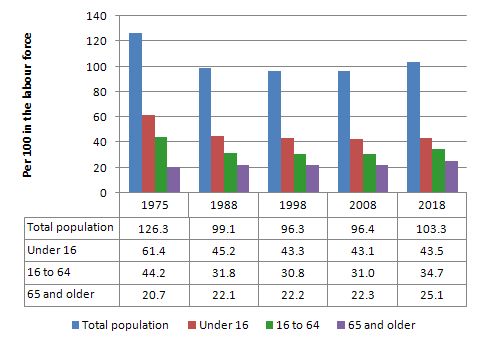

In the US Bureau of Labor Statistics publication – Monthly Labor Review (November 2009) – there was an article Labor force projections to 2018: older workers staying more active, which provided information about the dependency ratio in the US.

The publication defined the “economic dependency ratio” as:

… a measure of the number of persons in the total population (including the Armed Forces overseas and children) who are not in the labor force, per hundred of those who are.

The following graph (taken from BLS data) projects the economic dependency ratio out to 2018. No particular issues are noted.

In this paper – Age Dependency Ratios and Social Security Solvency – which was prepared by the US Congressional Research Service at The Library of Congress is interesting because it considers dependency ratio projections out to 2018. It doesn’t get the economics correct (presuming there might be a social security funding problem should thedependency ratio worsen) but it seems to get the demographics correct. It concludes:

If one considers the 130 year period from 1950-2080, the greatest demographic “burden” – when the number of dependents (children plus the elderly) most exceeds persons in the working-age population – is already in the past

Anyway my point isn’t to argue whether the dependency ratio as traditionally defined is rising or falling. I do not consider that to be an issue of social security solvency. However, I do see it as an issue in terms of the provision of real goods and services.

Interestingly, the BLS Monthly Review noted above also highlights the dramatic decline in participation rates particularly among males in the US.

The standard measures of dependency are partial at best. If we want to actually understand the changes in active workers relative to inactive persons (measured by not producing national income) over time then the raw computations are inadequate.

To get a more detailed view of “dependency” we consider the so-called effective dependency ratio which is the ratio of economically active workers to inactive persons, where activity is defined in relation to paid work. So like all measures that count people in terms of so-called gainful employment they ignore major productive activity like housework and child-rearing. The latter omission understates the female contribution to economic growth.

Given those biases, the effective dependency ratio recognises that not everyone of working age (15-64 or whatever) are actually producing. There are many people in this age group who are also “dependent”. For example, full-time students, house parents, sick or disabled, the hidden unemployed, and early retirees fit this description.

However, usually the unemployed and undereemployed are not included in this category because the statistician counts them as being economically active. But clearly in terms of defining the problem as being one of ensuring their is enough real output available for each of the future generations to enjoy they should be included. Not only for the dramatic loss of current output that mass unemployment creates but also the dynamic intergenerational impacts that unemployment delivers.

For example, teenagers who endure entrenched unemployment are typically not able to acquire the necessary skills which maximise their potential productivity in adult life. So the “dependency” is magnified across time even if they subsequently gain work.

If we then consider the way the neo-liberal era has allowed mass unemployment to persist and rising underemployment to occur you get a different picture of the dependency ratios. The adjusted ratio for the US at present and into the future is much worse than the official estimates would suggest.

I do not have time to day to make those calculations but the point is important.

The reason that mainstream economists believe the dependency ratio is important is typically based on false notions of the government budget constraint. So a rising dependency ratio suggests that there will be a reduced tax base and hence an increasing fiscal crisis given that public spending is alleged to rise as the ratio rises as well. So if the ratio of economically inactive rises compared to economically active, then the economically active will have to pay much higher taxes to support the increased spending. So an increasing dependency ratio is meant to blow the deficit out and lead to escalating debt.

These myths have also encouraged the rise of the financial planning industry and private superannuation funds which blew up during the recent crisis losing millions for older workers and retirees. The less funding that is channelled into the hands of the investment banks the better is a good general rule.

But all of these claims are not in the slightest bit true and should be rejected out of hand. It is not a financial crisis that beckons but a real one. Are we really saying that there will not be enough real resources available to provide aged-care at an increasing level? That is never the statement made.

The actual challenge of an ageing population is that more real resources will be required “in the public sector” than previously. But as long as these real resources are available there will be no problem. In this context, the type of policy strategy that is being driven by these myths will probably undermine the future productivity and provision of real goods and services in the future.

The irony is that the pursuit of budget austerity will undermine the ability of nations to provide these required flows of real goods and services. Fiscal austerity entrenches unemployment and usually leads governments to target public education almost universally as one of the first expenditures to be reduced.

Most importantly, maximising employment and output in each period is a necessary condition for long-term growth. The emphasis in mainstream integenerational debate that we have to lift labour force participation by older workers is sound but contrary to current government policies which reduces job opportunities for older male workers by refusing to deal with the rising unemployment.

Consider the state of the teenage labour market in the US – these are the workers of the future. The more productive they are the more likely that the US will be able to continue to provide high material standards of living to its citizens over the next 40-50 years.

If you wanted to see the real dependency problem in the US you might start with this graph which is taken from US Bureau of Labor Statistics data (Labour Force Survey) and shows the teenage (16-19 years) unemployment rate. It currently stands at 24.5 per cent.

Making a job available to all those who desire to work will have a positive impact on the true dependency ratio is desirable. But policies which entrench unemployment and encourage increased casualisation which allows underemployment to rise are not a sensible strategy for the future. The incentive to invest in one’s human capital is reduced if people expect to have part-time work opportunities increasingly made available to them.

These issues are about political choices rather than government finances. The ability of government to provide necessary goods and services to the non-government sector, in particular, those goods that the private sector may under-provide is independent of government finance.

Any attempt to link the two via fiscal policy “discipline:, will not increase per capita GDP growth in the longer term. The reality is that fiscal drag that accompanies such “discipline” reduces growth in aggregate demand and private disposable incomes, which can be measured by the foregone output that results.

Clearly surpluses helps control inflation because they act as a deflationary force relying on sustained excess capacity and unemployment to keep prices under control. This type of fiscal “discipline” is also claimed to increase national savings but this equals reduced non-government savings, which arguably is the relevant measure to focus upon.

Feldstein is among the senior economists who choose to ignore these realities. He is obsessed with privatisation and deregulation and so constructs everything within that lens. So his solution to the “impending fiscal crisis” is to propose a private “investment based accounts” as the basis for future Social Security in the US.

He claims that:

The challenge is how to assure that future retirees have accumulated adequate investment-based accounts to supplement Social Security and Medicare. Experience in a wide range of companies shows that a voluntary system can work if employees are automatically enrolled to have payroll deductions deposited into such accounts. Even though employees have the option to stop depositing, they do not do so. Inertia is a powerful force.

No, the challenge is to assure that future retirees have access to the desired level of real goods and services. The pension payments from government should be pitched at a level that provides an adequate access. That is not a challenge at all for a sovereign government. The challenge is ensuring there are the real goods and services available.

It might be politically determined that the society does not want the aged to have such access and future governments would have to deal with that political mandate and presumably cut aged pensions. But that would not be driven by any fiscal issue. As long as there is a mandate to provide a certain level of pension support and that level was backed by the availability of real goods and services then the US government will be able to honour that provision.

Feldstein knows that. But he wants a greater access to real goods and services for himself and his ilk and that can be more easily accomplished by denying access to others via spurious arguments about affordability.

Conclusion

The idea that it is necessary for a sovereign government to stockpile financial resources to ensure it can provide services required for an ageing population in the years to come has no application. It is not only invalid to construct the problem as one being the subject of a financial constraint but even if such a stockpile was successfully stored away in a vault somewhere there would be still no guarantee that there would be available real resources in the future.

The best thing to do when faced with an ageing population is to maximise incomes in the economy by ensuring there is full employment. This requires a vastly different approach to fiscal and monetary policy than is currently being practiced.

This should be accompanied by a strong commitment to public education to ensure that the potential of all citizens irrespective of private means or background is maximised.

If there are sufficient real resources available in the future then their distribution between competing needs will become a political decision. Economists have nothing to say about that.

Long-run economic growth that is also environmentally sustainable will be the single most important determinant of sustaining real goods and services for the population in the future. Principal determinants of long-term growth include the quality and quantity of capital (which increases productivity and allows for higher incomes to be paid) that workers operate with. Strong investment underpins capital formation and depends on the amount of real GDP that is privately saved and ploughed back into infrastructure and capital equipment. Public investment is very significant in establishing complementary infrastructure upon which private investment can deliver returns. A policy environment that stimulates high levels of real capital formation in both the public and private sectors will engender strong economic growth.

The worst thing for a government to do is oversee persistent unemployment and rising underemployment. The next worst thing they can do is hire lackeys like Feldstein to misrepresent the worst thing they are doing!

Postscript

Since when do people who end speeches with God Bless and all others who profess a love for humanity and forgiveness find it acceptable to publicly express satisfaction that another human being is dead No matter what that person did an eye for an eye is a poor basis for justice. Please don’t assume I support anybody or any cause – I just prefer consistency.

That is enough for today!

]]>

Re the postscript:

Not only “express satisfaction”, I’ve seen more restraint at footy finals.

Except, this time there were no winners.

Ask not for whom etc

Hello,

I’ve read many blogs in this site, really interesting and especially new.

I’ve read something about commercial banks and money creation, the vertical and horizontal transaction ecc. Really interesting.

But there is a subject that I would expound. Talk about the interest on loans by commercial banks, or generally talk about the interest. I’ve understand that the system of banking (loans create deposits) net to zero in aggregate, but I don’t want to see the matter from an accounting point of view.

What I mean is: we can consider the interest on loan that customers must to repay (If we see, in Italy for example, there is a situation where the interest became the same amount of the capital over the years) a cost that can cause inflation? I mean inflation = rise of prices.

I explain: In the balance sheet of a firm, the bank loan is a cost. I repeat, i don’t want to see the matter from an accounting point of view.

But we can agree that is a cost. Not only the interest, but also the capital is really a cost (the bank don’t consider the capital like a present).

The question is simple: the interest can cause a rise of prices? It’s an intrinsic factor of the idea of interest, the destabilization (in horizontal transactions)?

I don’t embrace the theory of Steve Keen or other that there isn’t enough money to repay the interest on loan. But I think that the interest,

in some situations, like a creedit freeze, or simply a difficulty by the firm to work in the market, (or “to compete in the market”, the essence of free – idiot – market view) can force the firm to raise prices or dismiss employees to repay the debt?

When I say destabilization I consider a situation where the simple presence of interest on loans, forces the businessman to produce over the “natural” to repay also the interest that is not lent by the bank (but it’s payable because there is in circulation), or to raise prices to bring costs down, or in general to do the hamster on the wheel.

What do you think about? not only Bill.

Thanks, have a nice day.

Dear Bill,

Killing of OBL was primary not about delivering revenge or justice. This guy had to be killed to prevent him from killing others. I would also pull the trigger and I think that this was everyone’s moral duty – with or without “consistency” or whatever. No matter how much we dislike the American foreign or domestic policy there are certain things which seem to be obvious. OBL was a self-proclaimed enemy of the West. He was after people like me or you – he would not distinguish between progressives and neoconservatives. He wanted to impose his moronic medieval ideology on other people – by sowing terror. I was born in a country where 6 million people (mostly Jews and Poles) were murdered by Hitler and Stalin. This could have been prevented if the West had attacked Germany in 1937 or 1938 – rather than had claimed “moral high ground” in Munich. I am happy that another mad idiot is dead before his dreams have been realised.

@Adam

I disagree. WW2 is a good example. The US administration didn’t simply order its soldiers to kill Hans Frank, Hermann Göring, … They set-up a trial. I find it irritating if a civilized government orders its soldiers to kill and explicitly not capture an evil individual to avoid the inconvenience of putting him on a proper trial.

First to Bill, thanks for the thorough and thought-provoking critique of the Feldman-Peterson-Forbes- approach to national economies and the public sector’s natural abilities under fiat monetary systems.

A note to Jake about the interest issue, I would like to recommend a view of the recent English-language video by Berlin School economist (Pr. Em.) Dr. Bernd Senf, who has put together what I see as the clearest pronouncement in one place on the total fallacy of debt-money creation by private banks.

It is available here:

http://www.blip.tv/file/4111596

Unfortunately, at least for me, you will not find criticism of that debt-money system among the MMTers.

Somehow, they are able to see a transition to a full-employment economy using fractional-reserve banking.

And given that an environmentally-sustainable, living-wage based, full-employment economy is about all one could ask for, who’s to argue with that?

Adam, if you want to be consistent you need to call for death sentences for those responsible for a million deaths in Iraq.

I agree with Billy’s postscript that it is strange to be asked to rejoice that strangers burst into someone’s house and shot people dead. I actually prefer hypocrisy about justice and love of humanity – which at least is the ghost of these things, an acknowledgement.

The purpose of taking out a loan is to give those without access to the real resources they would need to be marginally more productive access to financial resources that they can then use to purchase the real resources they need to achieve that margin. It only makes financial sense to take out a loan if the principle of the loan plus the interest on that loan accrued over its term is less than the increased marginal output the loan makes possible. Provided the loan is successful, the result of the loan will be an increase in the value of the real resources in the economy, and provided there is no government intervention, no change in the real dollars in the economy. If every loan was paid off, and the government didn’t increase the money supply to account for the increase in real resources in the economy, the result would be deflationary. This tendency can be offset by decreasing the interval between transactions, and by structuring some loans so they default.

When the loan is made, the account of the borrower is credited, while the account of the depositor (which fractionally backs the loan) is not debited, so through the term of the loan, up to 9 times the amount of the backing deposit (actually, this is not a real constraint, since banks don’t rely on just deposits to back loans, but can borrow money from the Fed to meet reserve requirements). So during the term of the loan, “virtual” money is created that is subsequently destroyed as the loan is paid back. The interest on that loan can come from other “virtual” money created from other loans, but on the assumption that all loans are paid off, this would necessitate an ongoing and growing debt load, sufficient to pay everybody’s interest obligations, a debt that could never in principle be completely paid off, but a debt that is held by numerous households, each of which may be able to pay off their share of that debt sequentially. If all loans are not paid off, the overall growth in the debt required to pay interest on prior loans can be mitigated through that default, as some of the “virtual” money created in the now defaulted loan will not be able to be recovered in order to cancel itself out, and thus, becomes real money. Again, all of this is under the assumption that the government does nothing to the money supply.

If the government creates new money to account for the increase in real resources made possible by successful loans, then interest can be paid off without requiring an ongoing and growing load of debt to pay for that interest and without the “need” to structure some loans to default.

Short notice to joebhed

I only looked a bit at the video (to long) and read the (german) entry on Wikipedia about Bernd Senf. My impression is that there is no fundamental difference between MMT and Bernd Senf, although he uses a bit different wording. He opposes interest (while many MMT proponents say that the natural rate of interest should be zero) – that bank profits from interest are undeserving, and that additional money should only enter the system true a public institution, that distribute it’s in a socially responsible way, to benefit society. (This is not really different from money creation trough government deficit spending). The main – potential – difference would be that the monney issuing institution should be a fourth branch of government (not the executive, nor the legislative, nor the judicial branch). Didn’t learn how it would be controlled – but this might be a way to adress one of the most importent issues for which I’m not hopeful with MMT – to have a an adequate deficit (one that is big enough to grant full employement, but not so big as to result in runaway inflation), you would need intelligent and responsible politicians, that actually care about the best interests of their people. And that would be – IMHO – the closest defintion of impossible.

Are there no responsibilities that come with tenure? Why does Harvard allow Feldstein to use their imprimatur to advance his clear lies in major financial publications? Is there no cost to Harvard in allowing their name to be dragged through the dirt of Feinstein’s ideological wet dream?

Ooops. I spoke too soon: Niall Ferguson – Sticker Shock. Maybe someone could remind Niall he’s an economic HISTORIAN and not an economist? I like Niall so much better as an historian. In fact, I don’t like him at all when he pretends to be anything else.

Joebhed,

no no, I’m not talking about debt-money. I know the subject, in some aspects I agree. I really think that there aren’t only two dimension debt/credit. Especially if we are talkin about a State that issues his currency.

But what I mean is only about the interest. Also, if the loan is lent not by a bank. My question is very simple,

I repeat: the interest can cause a rise of prices? It’s an intrinsic factor of the idea of interest, the destabilization (in horizontal transactions)?

This subject has also an historical and ethical aspect.

I don’t write about make money from money and other historical thoughts, I think you know.

But my question is purely economic.

I’m a bit baffled really why the US needs to tighten the belt on those who will be worst affected. With an annual military budget of nearly usd700 billion which is nearly 7 times that of the next closest rival, China, why is it not reasonable to make wholesale cuts there first (and not just trimming the icing that has been announced) ? It would take significant rethinking about how the US pictures itself as the global Headmaster/Policeman but I am surprised the people are willing to suffer a form of austerity before such expenditures are made.

Regarding Bin Laden, I think if the troops could possibly have captured him alive they would have. The Americans would have loved nothing more than to try him and through him into a rat infested cess-pit for the rest of his miserable life. Unlike Saddam who couldn’t give himself up quick enough and get out of the hole in the ground I suspect US troops were prepared for OBL to fight to the death given he has never been seen without an AK-47 close by.

-n

Stephen, Peter,

I think that there is an unbridgeable cultural gap between people who grew up in Poland/Russia/Ukraine/Belarus/Israel when the generations who witnessed the atrocities of WWII were still alive and these who were born in the “West” proper. We simply have a different historic experience and whatever I say or write will not be understood by a significant number of people coming from the different background. But my arguments will be properly understood by the overwhelming majority of the people who came from “my” side.

We cannot replace fighting the enemy who wants to terrorise and kill us with administering political correctness I am afraid. To me this is plainly naive. Has it ever worked? Please go to Libia and convince Gaddafi to stop murdering his own people. I think that the only argument which may work in the discussion with the guy who ordered the Lockerbie bombing is a Hellfire missile. He will not listen to anything else. He doesn’t have to.

This doesn’t mean that I am a great fan of the American foreign policy of the Bush era or the current neocolonial global order. This also doesn’t mean that I support the economic policy denying people the right to work in order to maximize the profits of some investors.

But sometimes it is our moral obligation to shoot to kill and don’t bother to philosophise about the “justice”.

Harvard and Chicago are two main centers that spill out neo-liberal junk economics.

—

jake, you got it right, interest rates raises are costs to a firms that do go to the prices. There is some literature on the subject and while mainstream economics tend to downplay this because it does not fit their preconceived ideas, they do not exactly deny it (I think) and some heterodox schools like post-keynesians emphasize it.

Adam,

if I may make an observation. Your viewpoint is obviously borne from a perspective of having lost relatives and perhaps vast parts of families and friends due to the atrocities of WW2 however if this attitude of revenge never ends then we can never have peace. I think this is the problem with modern Israel and its neighbours. Israel will never be oppressed again, I think that is clear, however with no empathy for its neighbours it will never quell the conflict by force.

I don’t understand why some Muslims would hail someone like OBL as a hero and martyr because I’m not Muslim but at a guess I could possibly think that many of them are not happy with how the US and Israel conduct themselves in those regions especially when oil is central to those.

OBL was a figurehead who has been dealt with and revenge achieved. It is now critical that the US and Israel attempt to offer an olive branch in the middle east so that progress can be made.

Adam, there is no gap. I am from Poland too. Naprawde. You just need to try to be consistent.

OBL killed 3000 people in US. US went back and killed 1,000,000+ people in the Middle East. By your logic Adam, would it be fine if the Muslims came back and killed 50,000,000 Americans?

Dear Bill

People who don’t work can only be supported by people who do. The higher the ratio of non-workers to workers is, the greater the burden will be on the workers. This is true regardless of how the non-workers are supported. Even with fiat currencies, a very high number of seniors is a problem because resources will have to be diverted from the workers to the seniors.

Seniors are more expensive to the state than children. Children live with their parents and require mainly schooling. Seniors live on their own in our societies and require a lot of health care.

I agree that a society as a whole can’t save except by storing goods or investing abroad. If an aging society decides to accumulate assets abroad, it can reduce its retirement burden because seniors will then be partially supported by foreigners. The problem with that strategy is that it is risky because it requires many foreign countries to run consistent trade deficits and then trade surpluses when that aging society starts selling off its assets abroad to maintain its seniors. We can’t just assign to foreigners the role that suits us.

Regards. James

James, agreed. I think the main point is that creating a pot of financial assets doesn’t solve the problem – it just becomes another subsidy to the financial industry since they will extract fees for creating the assets and another layer of fees for managing the pot.

@James Schipper

“I agree that a society as a whole can’t save except by storing goods or investing abroad. If an aging society decides to accumulate assets abroad, it can reduce its retirement burden because seniors will then be partially supported by foreigners.”

I think this is a good point. It’s necessary if a country is constrained by resources they must buy from overseas (e.g. Singapore needs energy and water from neighbours). To accumulate a sovereign wealth fund does not even require the Country to run a surplus budget. They just need the goodwill of foreigners to buy their own currency at an acceptable exchange rate.

I don’t think this kind of common sense plan is on the agenda of the neo-liberals though. They are looking to store funds in their own currency so baby boomers can compete for scarce resources to change their adult diapers. Can’t see future society accepting diminished

…diminished power and control over their destiny to look after a large crowd of infirm, greedy, selfish old folks.

(sorry for the double post… Fat fingers!)

Re James Shipper, May 4 @ 12:19.

It’s not at all clear to me that children are less of a cost in real resources than the elderly. Eighteen years eating food, consuming large quantities of other stuff, being educated, having larger living quarters to accomodate them… It’s not clear to me at all.

Adam,

I was born and raised in Canada, but lived in post-communist Poland for over 8 years. My parents lived through WW2 Poland, so did most of my uncles and aunts; one of my uncles fought in the Uprising as a 15-year-old. I think every one of them would love it if we could somehow pluck Stalin out of the past and make him stand trial in Poland for Katyn.

As for punishment, I am against the death penalty because it is far too LIGHT a punishment in such cases.

International law > Morals in the OBL question. War and violence is very seldom a good idea. Putting the power to kill humans into the hands of other humans is not stabilizing in the long run.

“I agree that a society as a whole can’t save except by storing goods or investing abroad.”

Bull.

Society can save domestically by investing in it’s laborforce and in infrastructure. A competent, healthy labor force is key. Infrastructure is a prerequisite to growth and improvements in infrastructure provide new opportunities at the same time as it frees up previously “locked up” capital for more productive investment.

Re: James Schipper,

I essentially agree with what you have stated, but it quite doesn’t accurately debate what Bill said, and i have have been one to pull this point up…

“Dear Bill

People who don’t work can only be supported by people who do. The higher the ratio of non-workers to workers is, the greater the burden will be on the workers. This is true regardless of how the non-workers are supported. Even with fiat currencies, a very high number of seniors is a problem because resources will have to be diverted from the workers to the seniors. ”

Read it again, he has stated that a government can never be constrained by the number of ‘financial assets’ (albeit our current ‘retirement schemes appear to be the accural of financial assets). he also acknowledges that …

>”The actual challenge of an ageing population is that more real resources will be required “in the public sector””. So he agrees with your point. To me what he appears to be espousing is that to ensure that these real resources are produced is to ensure an optimal outcome in terms of your available labour.

That means increasing their productivity, and that takes time. So train them now, particularly the “12.5% of the labour force that is under-utilised. I’m sure he’d have no problem with tranferring able bodied labour from the military, in real-product producing enterprise.

—

“Seniors are more expensive to the state than children. Children live with their parents and require mainly schooling. Seniors live on their own in our societies and require a lot of health care.”

Well, that’s a recent phenomenom, and only really confined to OECD countries. My wife’s family is from Malaysia, her parents live with her eldest eldest brother as they have no public sector income support. They stay at the eldest brother’s home, aid with the raising of their grand children and commit to household chores, while the two abled body adults in the household are committed to selling their labour.

I for one find it a superior model than what we currently have, where one parent is reduced in their vocational ability, to stay home and look after the children, or childcare is outsourced to corporations.

We have this model in our society, aided by welfare.

—

“I agree that a society as a whole can’t save except by storing goods or investing abroad. If an aging society decides to accumulate assets abroad, it can reduce its retirement burden because seniors will then be partially supported by foreigners. The problem with that strategy is that it is risky because it requires many foreign countries to run consistent trade deficits and then trade surpluses when that aging society starts selling off its assets abroad to maintain its seniors. We can’t just assign to foreigners the role that suits us. ”

‘Assign’ ??

The outflow from us to them is capital investment, the retreival is redrawing on our capital. It tends to be contractual, rather that a sovereign imposition.

James Schipper – what you are saying is only true when the economy is at full employment. Modern economies are generally demand constrained. So a rising dependency ratio, more non-workers for every worker, if supported by social insurance or whatever other means, will increase demand and employment and general prosperity, with less need for additional government spending and a Job Guarantee. All the intergenerational issues are just nonsensical divida et impera propaganda, which demographers laugh at. Seniors and children cost about the same to any society (though the cost to the state differs according to the state.) To quote demographer Joel Cohen, from memory – if a society can support people as children, it can support them in old age. The high dependency ratios of the 60s reinforced the prosperity then because it decreased leakage to savings. Middle aged workers save, while the young and old don’t.

Thanks for the reactions. Children can indeed be very expensive, especially very young ones. They need constant supervision while most seniors don’t. However, seniors are more expensive to the state. From the point of view of public finances, a population with 15% seniors and 25% minors is easier than a population with 25% seniors and 15% minors.

There is nothing sacrosanct about the age of 65. Contrary to widespread belief, Bismarck did not introduce an old age pension in Inperial Germany in the 19th century. It was a disability pension, and workers over 65 were assumed to be disabled, probably a realistic assessment at the time. Gradually, a disability pension evolved into an old age pension. My view is that the retirement age should gradually be raised to the age of 70. People who are unfit to work before 70 should have access to a disability pension, just as exists now in many countries for people under 65 who no longer are able to work. Some people stay fit and healthy till the age of 85. Today, they are in fact enjoying a 20-year holiday. Isn’t that a bit long?

If someone lives below his means, he needs somebody else who lives above his means, and vice-versa. it is impossible for the whole world to live above or below its means, just as it is impossible that every country has a trade surplus or deficit. This implies that a country that decides to live below its means in order to prepare for a retirement boom has to find foreigners who are willing to live above their means. What if all countries want to live below their means? We can’t just assume that foreigners will play the role that we want them to play. That’s why it is best for every country to find domestic solutions for a retirement boom, just as it is best for every country to aim for a trade balance and not a trade surplus or deficit.

An essential point to remember, and one that is overlooked by advocates of funded pesnions, is that we cannot transfer purchasing power to te future. If Peter lends money to Paul, he transfers purchasing power to Paul in the current period. When Paul pays him back 5 years later, purchasing power is transferred from Paul to Peter in what is then the current period. What Peter has not done is to transfer purchasing power to the future. That can’t be done financially, only physically by storing goods for future consumption.

Have a good day everybody. James

What is the MMT position on the deficit (in moral behavior) in the execution of Osama bin Laden ?

I understand, from MMT, that deficits are always to be examined in context.

Vassilis, that depends on whether you are morally sovereign or not. I’d say it’s likely to be inflationary.

To GoodHabit

Thanks.

I didn’t think that Senf opposes interest, per se.

He opposes interest on ALL new money being created as an interest bearing debt.

And today, Since Bretton Woods I, all new money must be created as an interest-bearing debt.

Were money permanently created without any debt, as Senf advocates, then money would exist and be lent TO banks for loan-making purposes at interest, like people think they do now.

There is an interesting connection between MMT’s deficit-spending-without debt proponents, including Bill and Warren, and the debt-free money economists such as Senf and others. I agree.

But the problems of compounding interest on all money created as a debt is not a foundation issue for MMTers.

Rather, it is a “situational” remedy to faults that arise in the functional finance model.

So, adequate private money creation managed through proper monetary policy controls would eliminate the need for the temporal debt-free money solution, and fractional-reserve banking using debt-based money rule the day.

That’s a big difference to me.

The proper and priority use of the money system should not be left to situational variations.

It should be based on sound science, and if you actually listen to the entire presentation, you’ll see why Senf concludes the debt-money system fails that test.

Adam “We cannot replace fighting the enemy who wants to terrorise and kill us with administering political correctness I am afraid. To me this is plainly naive. Has it ever worked?”

– In the movie “Gandhi” they gave the impression that Indian independence was gained by people just defiantly receiving violence without retaliating. If there is any historical truth in that film (and I thought it was historical) then that is a great example. It is an incredible that so many people took part in such a heroic effort. In that film Gandhi says that the Nazis could be defeated in the same manner. In Libya some pilots defected because they did not want to bomb peaceful protesters. Perhaps Gadaffi might have been ousted already and fewer people killed if the protesters had stayed unarmed???

James: If someone lives below his means, he needs somebody else who lives above his means, and vice-versa. it is impossible for the whole world to live above or below its means Yes to the vice versa, no to the initial statement. It is of course impossible for a closed economy to live above its means. But it is very easy to live below it, and those who live below have no need for somebody else living above. Living below can amount to running an economy below full capacity, below full employment, which is unfortunately very common. (Living below could also be understood as accumulating claims on the “live-abovers” (or for the future) while at full employment, which is the case I think you have in mind.)

Dear Some Guy

I agree that an economy can function below its capacity, but what I meant is that, in a closed economy, consumption and investment have to be equal to production. In a country with a closed economy, you can’t have a situation in which GDP is 100 billion, consumption is 70 billion, investment is 20 billion and 10 billion is set aside for the future. Then there will be demand gap and GDP will eventually fall to 90 billion.

However, it is possible to store goods for the future. Suppose that a country only produces grain. Annually it produces 10 million tons, but it consumes only 9 million and 1 million is reserved for the future. In that physical sense, yes, it is possible to live below its means, even within a closed economy.

The point that always should be emphasized in discussions about retirement is that a country as a whole can’t save purchasing power financially if it has a closed economy, no more than a country can borrow form future generations. Even if a country has no government retirement scheme, its non-working seniors will still maintained by younger people.

Nobody can be supported by his capital alone. Suppose that in Australia, all people under 65 were to die. Then seniors would become owners of all capital in the country. However, they would also be starving because capital without labor is like a truck without a driver. No matter how much capital there is, ultimately we are all kept alive by labor. A man who owns 20 houses and lives off his rental income is not really supported by his houses but by his tenants.

People who say that aging problems can be solved by investment in the stock market overlook that stocks have value only because corporations have value, and corporations only have value because their employees are sufficiently productive. No matter how you turn it, everyboy is ultimately supported by labor, either his own or somebody else’s.

Yes, I quite agree with your main points. The set-aside for the future, or grain storage would be classified as investment, which measures how the economy is living below its means. Stock market investment for a nation’s retirement schemes are a financial absurdity for the reasons you present. (Unless the government plans to run a socialist state by direct ownership of the means of production!) Only the real national wealth and income matters. Which is why the US’s gross overtaxation building up an SS trust fund on the advice of supreme idiot Greenspan was so destructive – it significantly lessened the real wealth that the baby boomers were building up, destabilized the economy and gave more scope for the US government’s multifarious welfare-for-the-rich, predation-on-the-poor schemes to redistribute wealth upwards.

But there is no real aging problem, absent an event like everyone under 65 dying. A bigger generation will build up that much more capital, real wealth to support it later. As I said, if economies are mismanaged as most have been for 40 years, a retirement bulge, like a baby boom, can even be a boon, pushing up demand. Perhaps what Greenspan’s puppetmaster, if there was one, feared back then was the return of the good times in the 2010s, which had to be prevented in the 1980s. The rule that today’s economic orthodoxy gets everything exactly backwards – e.g. what they call bad is good and vice versa – is amazingly rarely wrong.

Thanks a lot Sir, for your thoughful and clear exposition.

One year after this blog entry, the foundations exposed in this article are still more relevant, exposing what is the fundamental corruption of the economic discourse: to try promote policies in the name of the common-good which in fact correspond to particular interests.

Thanks