It's Wednesday, and as usual I scout around various issues that I have been thinking…

Better off studying the mating habits of frogs

Day 3 in the Land of Austerity (LA LA land). I sometimes enjoy a regular little private activity now which I call for want of a better term – “I told you so” – and which involves going back to articles that were written prior to the crisis about macroeconomic trends and having a laugh about their contents. Today I thought I might share one of these articles with you because it came up in a telephone conversation I had today with a British journalist who was seeking background on a story they were writing. Their contention was that the ECB is in danger of going broke. I suggested (nicely) that they would be better off focusing on the mating habits of frogs in the Lake District of England than writing a story like that. Here is why I said that.

Here is the fun bit. Consider this Bloomberg Business Week gem from February 3, 2003 – Is the Bank of Japan Barreling toward a Bailout? which carried the sub-title – “Its spending spree could make the unthinkable a reality”.

Then you read on and find:

How bad are things in Japan? So bad there’s serious apprehension that the Bank of Japan might need a government bailout. Sure, central banks normally can’t run out of money, because they own their currency’s printing presses. But the BOJ is a special case. To enable the bank to play its role as lender of last resort for both Japan’s central government and its rickety commercial-banking system, BOJ Governor Masaru Hayami’s Policy Board reluctantly launched an enormous spending spree that could someday burn a very big hole in the bank’s balance sheet.

Excuse me? “Sure, central banks normally can’t run out of money, because they own their currency’s printing press”? But? They are using that capacity to purchase assets in the financial markets? And? Some day things will turn bad? How? Don’t they own “own their currency’s printing press”?

If that wasn’t enough you read further:

Since 1997, the central bank’s outright purchases–as opposed to repurchase agreements–of Japanese government bonds have exploded, to a cumulative total of $471 billion. To keep the money markets flush with cash, the bank now devours some $10 billion in bonds a month on the secondary market. At that rate, it’ll absorb about 40% of all new Japanese government bond issuance in 2003. On top of that, it announced plans last year to buy as much as $17 billion worth of stocks from commercial banks, which need to sell off their corporate shares to raise cash.

And? What happened next? Answer: Not a lot. Interest rates remained around zero. The Bank of Japan is still functioning as it normally does and the flowers still bloom in spring.

But in February 2003 we read that:

The bank has already crossed a dangerous line … Concerned staffers see a grave situation if the central bank takes on risky assets and they plunge in value. Already, they point out, the bank’s holdings–including government securities, gold, cash, overseas currencies, and foreign bonds–add up to $1.05 trillion. That’s 60% more than the assets of the U.S. Federal Reserve.

I love it when journalists make up stuff or have lunch with some right-wing extremist mate of theirs who works in the mail room at the BoJ or wherever and they immediately source the story to “concerned staffers” or “reliable sources” or whatever.

The point was that in 2003 they were predicting imminent collapse because the BoJ had already “crossed a dangerous line”. Which line exactly was crossed? Answer: the “dangerous line”. And which line is that? Answer: its obvious – it is the “dangerous line”. Okay, what is exactly dangerous about the “dangerous line”? Answer: no further analysis provided.

Just in case the Business Week readers were sufficiently terrified that the entire Japanese banking system was about to go broke, the article also decided to play another trump card – yes, you guessed it – the hyperinflation with a complex currency crash central bank humiliation appendix story. They wrote:

… more massive central bank bond purchases could set the stage for a bubble that would drive prices skyward–until investors, worried that the bank had lost all discipline, panic and hit the sell button, sending prices crashing. One official notes that just a 10% fall in the value of the central bank’s bond portfolio would wipe out close to $42 billion in reserve capital. If things really spin out of control, the central bank at some point might have to turn to the government, which holds a 55% stake, for a capital infusion. That would be humiliating for a rich country such as Japan. More important, such a bailout could forever undercut the bank’s independence. Watch out, Mr. Koizumi: A central bank’s credibility is one asset that’s irreplaceable.

What happened? Answer: none of the above. How many times has a similar article with similar predictions been written by journalist on this publication and a multitude of others? Answer: I can only count on my fingers.

Inflation didn’t rise in Japan – not generally or in specific-asset classes. There was no panic “hit and sell” button pressed. The yen has been stable. The BoJ continued to expand its balance sheet. End of f%*!ing story.

In case you want to learn more about what the Bank of Japan actually does you might find this “official” site interesting – The Bank of Japan’s Policy Measures during the Financial Crisis.

Between 2001 and 2006, the Bank of Japan conducted two types of interventions (in addition to setting interest rates) which impacted on the asset and liability side of its balance sheet.

First, it ensured that the commercial banks had excess reserves (expanded the monetary base) mostly by purchasing long-term government bonds in the secondary markets which expanded the size of its balance sheet. This is what we consider to be a liability side measure which is alleged by the mainstream commentators to increase liquidity in the commercial banking system and provide more funds for lending. It actually operates to drive down yields on long-term financial assets (bonds) and keep rates in that maturity segment lower than might otherwise be the case.

Second, the BoJ also conducted what economists term “credit easing” policies by purchasing a range of “unconventional” assets (asset-backed securities etc including commercial paper) but keeping the size of the balance sheet unchanged (so operating on what economists call the “assets side” of the balance sheet). In other words, the central bank takes risky assets off the commercial banks which acts as a substitute for traditional financial intermediation.

Both measures are lumped together under the heading quantitative easing although the economics literature distinguishes between quantitative easing (changing the size of the balance sheet but holding the composition of assets constant) from credit easing (changing the asset composition).

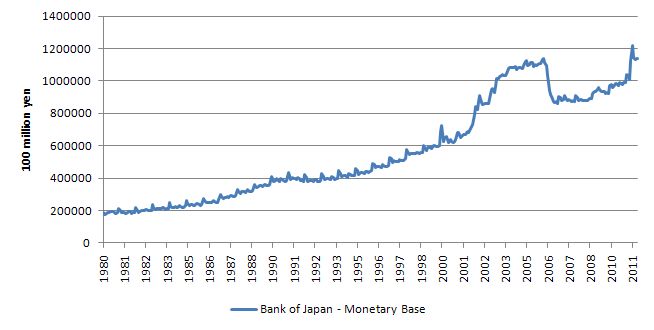

The pre-crisis quantitative easing period in Japan ended in 2006. The following graph shows the evolution of the monetary base in Japan from January 1990 to August 2011 (data is available HERE).

In March 2006, the Bank of Japan announced that they would end this phase of QE (the inflation rate became positive again – their aim was to stop dangerous deflation) and over the next year they gradually drained excess reserves from the system while keeping its policy target rate at around zero. The decline in the monetary base was very orderly.

So after the mad Business Weekly article was predicting mayhem, the BoJ quietly went about its business with total control over the short-term interest rate and term structure of longer maturity rates, in a zero inflationary environment with all government bond issues being oversubscribed (that is, no panic sell off).

But while my private “I told you so” activity always amuses me, I had another motive for sharing it today – as signalled in the introduction. People are still claiming the European Central Bank (ECB) is in danger of incurring massive losses and might go broke. Journalists are actually spending precious time researching this non-issue.

This 2010 paper by one Ansgar Belke – How much Fiscal Backing must the ECB have? The Euro Area is not the Philippines also confirms that the ECB cannot go broke and that “fiscal backing is not necessary for the ECB”. When reading this paper you should be careful – it is full of mainstream myths and is essentially highly dependent on another paper by Willem Buiter which I reference below. But in the essential point about central banks being immune from bankruptcy, the paper is correct.

The Belke paper notes that:

… all losses incurred by the Eurosystem in the pursuit of its monetary and liquidity operations, to be shared by all 16 national central banks in proportion to their shares in the ECB’s capital. But while the Eurosystem as a whole shares any losses incurred by its individual national central banks, no fiscal authority stands directly behind the ECB, and, hence, there is no mechanism for recapitalizing the Eurosystem as a whole available.

Is that a problem?

Willem Buiter noted in his 2008 Discussion Paper – Can Central Banks Go Broke? – that in “the usual nation state setting” there is a unique “national fiscal authority” (treasury) which “stands behind a single national central bank”. He concludes in this situation that:

There can be no doubt … the fiscal authorities are, from a technical, administrative and economic management point of view, capable of extracting and transferring to the central bank the resources required to ensure capital adequacy of the central bank should the central bank suffer a severe depletion of capital in the performance of its lender of last resort and market maker of last resort functions.

Does this mean that central banks cannot go broke? Answer: no.

Willem Buiter provides the qualification that is essential:

… the central bank can always bail out any entity – including itself – through the issuance of base money – if the entity’s liabilities are denominated in domestic current and nominally denominated (that is, not index-linked). If the liabilities of the entity in question are foreign-currency-denominated or index-linked, a bail-out by the central bank may not be possible.

Which is the standard Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) definition of a risk-free sovereign government – one that only issues liabilities in its own currency. If the consolidated government sector – the central bank and the treasury – issue liabilities (for example, take on debt) – that is denominated in a foreign currency, then insolvency becomes a possibility.

What about the Eurozone, where there is no fiscal authority? In the Eurozone, the pecking order is that the member state treasuries are deemed to guarantee their own national central banks which “own” the ECB and which provide lender of last resort facilities to their own banking systems. There is no fiscal authority backing the ECB but despite all the legal niceties (complexities) involved in how the national central banks might carry out their lender of last resort duties, the reality is that the ECB is the ultimate lender of last resort in the EMU

The other point to note (which is made by Buiter and the 2010 Agnes paper) is that it :

… is not necessarily the case that a central bank goes bankrupt even if its equity capital is completely depleted by its engagement in unorthodox monetary policies. The reason is that there are differences between central banks and commercial banks and a static visual inspection of the central bank balance sheet does not convey a complete picture.

Why is that? Belke provides the example of the US Federal Reserve which “could buy up the entire outstanding stock of privately held US Federal debt today, i.e. it could be able to monetise the public debt” and “if the Fed loses capital it will not go bankrupt like a regular company: it will just print the money to make up the difference – and this is meant literally”.

Further:

The ECB cannot go bankrupt according to common comprehension because “it is sitting at the fountain-head of money” which it can create by itself.

While the mainstream economists would consider this to be dangerously inflationary if the central bank acted in this way the point is that at least that observation (erroneous or not) takes the debate beyond the inane level of insolvency.

Please read the following blogs – Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary – for further discussion.

This discussion then led me to thinking about the current role of the ECB which I touched on in yesterday’s blog – Impeccably running a sinking ship.

In this August 2011 paper – Only a more active ECB can solve the euro crisis – Belgian economist Paul de Grauwe wonders why the attempts by the Euro bosses to quell the crisis has so far failed. He says:

Government bond markets in a monetary union are extremely vulnerable. The reason is that national governments in a monetary union issue debt in a ‘foreign’ currency, i.e. one over which they have no control. As a result, they cannot guarantee to the bondholders that they will always have the necessary liquidity to pay out the bond at maturity. This contrasts with ‘stand alone’ countries that issue sovereign bonds in their own currencies. This feature allows these countries to guarantee that the cash will always be available to pay out the bondholders.

Which is MMT orthodoxy and confirms that the problem is in the Euro itself and has little to do with lazy Greek workers or any other side-issue (not that I am agreeing that Greek workers are lazy).

De Grauwe correctly notes that the Euro design means that member governments are at the mercy of the markets just like private banks. Which means that if bond markets form a view that a particular member state is to risky, a liquidity crisis can easily ensue, driving up yields and forcing that nation into insolvency.

It is clear that the same process cannot occur in a nation that is fully sovereign. In that sort of monetary system the sovereign government rules over the bond markets. Please read my blog – Who is in charge? – for more discussion on this point.

So what is the current solution for the EMU? De Grauwe says that within any monetary system the lender of last resort facilities are designed to avoid bank collapses and :

The only institution in the eurozone that can perform this role is the European Central Bank. Up until recently, the ECB has performed this role either directly by buying government bonds, or indirectly by accepting government bonds as collateral in its liquidity provision to the banking system.

In other words, the only thing that has been keeping the eurozone from collapsing in the current crisis has been the ECB action which is now under attack from the conservatives.

De Grauwe analyses some of the claims that have been made by the conservatives. The first, is “What if the central bank loses money?” – that is, the argument that the ECB is exposing itself to credit risk (buying up dodgy assets) and could go broke. I don’t think De Grauwe’s explanation hits the nail on the head (he uses a clumsy and incorrect analogy with a private insurance company) but his essential point is that “the ECB should not really worry about the fact that once in a while it loses money” is sound.

I would say it shouldn’t worry at all – ever if it “loses” money. The goal of lender of last resort interventions is to maintain the public good we term financial stability. There is no real concept of profit and loss when we are talking at that level of public purpose. How do we value the maintenance of financial stability? Certainly not in narrow private profit and loss terms (market rates etc).

De Grauwe correctly notes that “even if these losses are so large as to wipe out the equity of the central bank” there is no problem because:

In contrast to private firms, the central bank can live happily with negative equity, because the central bank can always fill the holes by printing money.

His other arguments are outside today’s blog. He worries about governments issuing “too much” debt which is a mainstream argument he accepts. I consider the analysis to be flawed.

He also considers the “What about inflation?” argument – that is, “Doesn’t an increase in the money stock always lead to more inflation, as Milton Friedman taught us?” He notes that quantiative easing (central bank buying government bonds) “increases the money base (currency in circulation and banks’ deposits at the central bank)” but does not necessarily “mean that the money stock increases”.

He suggests that the increase in the base has not translated into an increase in money stock because banks have “piled up the liquidity provided by the ECB without using it to extend credit to the nonbanking sector”. Again, De Grauwe becomes mainstream and misinterprets the way the banks operate. They are not lending because there is a general malaise and a lack of credit worthy borrowers. The banks could lend with the buildup of reserves if there was higher confidence in the economy.

It is a totally spurious argument to suggest the increase in reserves has made it easier to lend but they are “holding cash for safety reasons”.

De Grauwe then suggests that if inflation was to be an issue, the central bank “can always sterilise the effects of these operations on the money base” by selling other assets (that is, changing the composition of the central bank balance sheet rather than its size). Again, this is mainstream thinking. The point is that the increase in bank reserves do not change the inflation risk in the system. That risk comes from the relationship between the growth in nominal spending relative to the real capacity of the economy to produce.

It has nothing to do with the size or composition of the central bank balance sheet.

But I agree with his conclusion that:

There is a need for a fundamental overhaul of the eurozone’s institutions. In that overhaul it is essential that the ECB take on the full responsibility of lender of last resort in the government bond markets of the eurozone. Without this guarantee, the government bond markets in the eurozone cannot be stabilised and crises will remain endemic.

But I would go further and conclude that while this would work in the short run, the basic design flaw in the EMU – a lack of a national (elected) fiscal authority – would remain.

A related blog for this topic is – The US Federal Reserve is on the brink of insolvency (not!) – which might be of interest.

Conclusion

Time to finish.

Now, I have a date with the Australian Broadcasting Commission (ABC) and their early morning show. This is a talkback program that runs from 4 am to 5 am every morning and provides an extended interview (today OZ time with me on unemployment) with questions. So a chance to have a good discussion. When I do this segment back home it means an early rise but tonight it will begin for me at 20:00 a much more civilised time. It is Trevor Chappell’s ABC Local Radio Overnight program if you are up at this time.

That is enough for today!

Czech National Bank has negative accounting capital (last time I checked) of approximately 6.5bn EUR (at the last time I checked exchange rate). If I am not mistaken Central bank of Israel also have negative capital. And Chile as well.

While ECB will remain operational with negative capital, it does not mean it will be *allowed* to operate with negative capital. This point is effectively supported by the two recent top level departures from ECB. NCBs are shareholders but we live in the world of limited shareholder liability. Obviously this is not an issue for normal financial systems like in Czech Republic.

Brad deLong is also having fun with the “social security is a Ponzi scheme” meme

http://delong.typepad.com/sdj/2011/09/a-platonic-dialogue-on-the-ontological-status-of-social-security.html

Thanks so much for sharing your private diversion, and using it to instruct. I’ve read this several times over now. Hilarious! And informative… comme d’habitude!

If Greece left the Euro zone what happens to their share of the ECB purchases?

Just another thought can we outsource the UK MPC to the Bank of Japan as they appear to have the necessary expertise?

Bill, you should post those interviews and the like that you do. I’m sure the radio stations etc. would send you an mp3 or something…

Chris says:

“If Greece left the Euro zone what happens to their share of the ECB purchases?”

Someone must have a more detailed answer but here’s mine. Greece should demand a full return to pre-Euro conditions, which means, among other things, that ECB hands back the foreign currency assets of Greece’s central bank. Afterwards, Greece will deal, separately, with the holders of its debt – and these are private institutions and not other member-states. A generous haircut would be the first item on that agenda, naturally. These days, I’m personally very fond of crewcuts.

ECB purchases and Greece’s share in them should be handled the same way an investment fund handles the assets of a participant who opts out. Greece does not owe ECB one cent.

http://www.abc.net.au/overnights/stories/s3317713.htm?site=melbourne

[Bill edit: this link takes you to the ABC radio program “Overnight” page and a segment that I appeared in on Wednesday]

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zRrnldG-3Kc

[Bill edit: this video is a television interview with three financial commentators one of which is Michael Hudson]

Dear Rog and Kritjan

I have approved these two unexplained links this time. In general I will not approve links that are not put in context as to why we should be clicking them. I also do not have time generally to monitor a 25 minute video or audio stream to ensure the link is something I wish to send the readers to. I will never approve a link that sends the reader to pure propaganda that makes erroneous claims about the monetary system. Some my call this censorship and I get attacked daily when I deny approval to some crazy Austrian goldbug rant. But my view is that there is enough of that and I don’t wish to provide an audience for it via my work here.

So please provide a context and rationale for posting a link when doing so.

best wishes

bill

Fair enough Bill, I had thought that information contained in the URL would have been sufficient.