Edward Elgar, my sometime publisher, is interested in me updating my 2015 book - Eurozone…

Wir wollen Brot!

Bloomberg News carried the headline today (November 23, 2011) – Germany Sees No ‘Bazooka’ in Resolving Debt Crisis as Spanish Yields Surge – which reiterated various statements in recent days from German political leaders eschewing any role for the ECB in defending the EMU from impending collapse. The Germans seem to have very selective memories. There was a time – much closer to today than their hyperinflation experience – when their citizens were cold and hungry and only a major fiscal intervention saved them from greater austerity. There was a time when they marched in the streets with placard declaring “Wir wollen Brot!”.

While the Bloomberg article focused on the spreads between Spanish government bonds and the German bund benchmark in recent days and the fact that the Troika is bullying the new Greek government to articulate in writing their “commitments to austerity measures”, the crisis deepens because over the last week, the French position has started to look very shaky.

The ten-year French bond spreads which was at 0.71 in September 1, 2011 is now at 1.58 (and rising) (Source). With Italy now one the “austerity-default” treadmill that Greece has been on for the last few years, and France coming into the picture, the situation is getting desperate.

Bloomberg quoted Michael Meister, finance spokesman for Chancellor Angela Merkel’s Christian Democratic bloc who told them in a telephone interview that:

We don’t have any new bazooka to pull out of the bag … We see no alternative to the policy we follow.

That is, the Germans are deeply opposed to the European Central Bank from becoming a lender of last resort.

As an aside, we should clarify terminology. When economists talk about the central bank playing the role of “lender of last resort” they are referring to the capacity of the central bank to lend to its member (private) banks – that is, provide reserves in return for collateral at some discount (penalty) rate.

This point was made at a Press Conference. by the Bank of England Governor last week (November 16, 2011) accompanying the release of the Bank’s Quarterly Inflation Report – 16th November 2011.

Mervyn King said that the usual concept of “lender of last resort”:

… is a million miles away from the ECB buying sovereign debt of national countries, which is used and seen as a mechanism for financing the current-account deficit of those countries, which inevitably, if things go wrong, will create liabilities for the surplus countries. In other words, it would be a mechanism of transfers from the surplus to the deficit countries. That’s why the European Central Bank feels, and with total justification, that it is not the job of a central bank to do something which a government could perfectly well do itself but doesn’t particularly want to admit to doing …

The only circumstance in which looking at the data for the euro area as a whole has merit is in realising that actually the euro area does have the resources, if you were to regard it as a single country, to make appropriate transfers within itself. It doesn’t actually need transfers from the rest of the world. But the whole issue is, do they wish to make transfers within the euro area or not? That is not something that a central bank can decide for itself. It is something that only the governments of the euro area can come to a conclusion on. And that is the big challenge that they face.

I agree with the Governor that the term “LOLR” is being misused in the current debate. But I disagree that the ECB’s job is not to “do something which a government could perfectly well do itself but doesn’t particularly want to admit to doing”. That statement is catogorically incorrect when applied to the governments in the EMU.

The member states in the EMU cannot spend without funding that spending via taxation and or debt-issuance. The only institution in the EMU that can spend without recourse to prior funding is the ECB. That is the consequence of the flawed design of the monetary system that the neo-liberal conservatives in Europe forced upon the member states at the inception of the union.

It might not be the job of the ECB as they define it to bail out governments but it is that or the system collapses. It is clearly the job of the ECB to ensure there is financial stability in the monetary system that is it as the “centre” of. Central banks exist to guarantee financial stability. At present, there is a major risk of financial mayhem in the Eurozone and that has to be a primary focus of the ECB.

They cannot hide behind the claim that all they are concerned about is price stability. If they continue to assert that “independence” then they won’t have a monetary system to worry about.

Mervyn King clearly realises though that the ECB “does have the resources” and could “make appropriate transfers” if there was a political will to do so.

But the Germans have been supporting a nonsensical mendacity – trying to get China and Brazil – vastly poorer nations to lend them money instead. They somehow don’t have any sense of pride.

The UK Telegraph (November 20, 2011) in this article – Spain – the fifth victim to fall in Europe’s arc of depression – said that:

German finance minister Wolfgang Schauble – the most dangerous man in the world – is imposing a reactionary policy of synchronized tightening on the whole eurozone through the EU institutions, invoking a doctrine of “expansionary fiscal contractions” that has no record of success without offsetting monetary and exchange stimulus. What is abject is that EU bodies should acquiesce in this primitive dogma.

The “most dangerous man in the world” certainly has been strident in recent months in his view that the only solution is extended austerity.

Wolfgang Schäuble wrote in Financial Times (September 5, 2011) – Why austerity is only cure for the eurozone that:

The recipe is as simple as it is hard to implement in practice: western democracies and other countries faced with high levels of debt and deficits need to cut expenditures, increase revenues and remove the structural hindrances in their economies, however politically painful …

There is some concern that fiscal consolidation, a smaller public sector and more flexible labour markets could undermine demand in these countries in the short term. I am not convinced that this is a foregone conclusion, but even if it were, there is a trade-off between short-term pain and long-term gain. An increase in consumer and investor confidence and a shortening of unemployment lines will in the medium term cancel out any short-term dip in consumption …

… governments need the disciplining forces of markets …

He might be convinced that austerity is good for a nation but the evidence is clearly pointing to the fact that there is massive short-term pain involved which is undermining the achievement of the basic objectives – to reduce budget deficits.

Further, this ascetic idea that long-term gain will come – defies the known intergenerational effects of entrenched unemployment. Yes, growth will return eventually but from a much lower base and be restricted in its potential growth path by the lack of investment now (productive capacity is not being added).

But even when growth returns, the private saving caches that were accumulated over years of hard work for many will have been wiped out and millions of citizens (the youth of today) will be without work experience and adequate skills.

Economists like to use expressions such as “medium-term”. When is that? Europe has already been immersed into this crisis for 4 years or so now and it is deepening. There will be very little growth next year as world export markets soften (already we are seeing that in Asia) as a result of the austerity being imposed on economies by governments.

2013 is likely to be subdued at best. So when is the medium-term when the big private spending comeback cancels “out any short-term dip in consumption”? And will it cancel out the major short-term collapse in investment (which reduces potential growth)? And will it replace the lost income that has seen private saving balances wiped out? And will it restore the hard-won pensions that are being carved into by malign governments?

My answers to all those questions are an emphatic NO.

I am doing some research at present and will report in due course – but my surmise is that the economic damage being done in Europe at present will exceed the damage incurred during the Second World War when Germany was once again on the rampage! Note I am only considering economic dimensions. The personal damage during the 1939 War were, of-course, immense.

Schäuble gave an interview to the Focus Magazine on November 14, 2011 and said:

The key issue for the euro zone is the trust of the financial markets. What the financial markets can’t really comprehend is 17 countries with one currency. How does it work? We have an independent central bank that is not to be exploited to finance our governments. But we have not agreed on common fiscal policy up to now. We believed that the Stability and Growth Pact would keep things on an even keel. It was a step in the right direction, but didn’t go far enough. That’s why we have made it more stringent. The improved Pact, which has just been finalised, has more – and sharper – teeth, and takes effect at a much earlier stage. In addition to this, we must move fiscal policy further into the community sphere in Europe, and strengthen its institutional foundations.

As I discussed in this recent blog – The hypocrisy of the Euro cabal is staggering – the Germans violating the SGP for several years from 2001 to 2005. If they hadn’t have maintained the level of fiscal stimulus (above that permitted under the Treaty) then their economy would have probably fallen into recession.

The evidence is clear – austerity is killing growth and private confidence is deteriorating not improving. Schäuble’s claim that a private recovery is imminent is just a statement of religious doctrine – there is no theory or evidence to support it.

Last week (November 18, 2011) he gave a speech – Finanzmärkte und Politik: Lehren aus den Krisen (“Financial markets and politics: Lessons learned from the crises”) at the Frankfurt European Banking Congress and said that the ECB should never take on the role of “lender of last resort” because if they did “the financial markets would simply presume the euro would not remain a stable currency”.

Yesterday (November 22, 2011) the German Finance Minister was at it again. He gave a speech to the German Parliament and Reuters reported that he reiterated the German position that they would not risk price stability. They quoted him as saying:

We will do everything to ward off the dangers for the stability of the euro as a whole. But we will only do that in a way that we can be sure that the joint European currency remains a stable currency. That’s the promise we gave for the common European currency – that it is a stable currency with an independent central bank that is not there to be a state financier.

This UK Guardian article (November 16, 2011) – Hard truths about the euro from Mervyn King – also falls prey to the conventional logic by claiming the ECB would face insolvency if it took over the risk currently being borne by the member state governments in the EMU:

The big point remains: if the ECB were to subscribe for large quantities of new Italian and Spanish debt it would be accepting a risk that ultimately falls on all governments in the eurozone, since they’re people who stand behind the ECB itself. If the new Italian and Spanish bonds on the ECB’s books were to turn rotten, the losses would fall on the rest of the eurozone. So it’s best to be explicit about that credit risk, rather than to pretend it can be lost in the wash of everyday central banking activity.

Put another way, the essential problem is that the eurozone doesn’t have a single government with a single balance sheet. If it did, the option of printing a heap of cash to erode the value of euro-denominated sovereign debts (at the expense of rich northern European countries) would exist. But it is not allowed. Them’s the rules in the eurozone: members aren’t liable for each others’ debts.

But the rules allow the ECB to buy as much debt as it likes via the secondary markets which is equivalent to buying them at primary tender – for all intents and purposes.

While the member states in the EMU do face insolvency risk because they operate with a foreign currency (the Euro), the ECB has no risk. It has an infinite minus one euro cent capacity to issue Euros into the monetary system.

The rules that the EMU have put in place do not negate that fact. They only define ways in which that capacity has to manifest. And – they could be changed to make the ECBs role for functional and direct.

But they don’t negate the fact that the ECB cannot go broke in terms of any Euro-denominated liabilities.

All of this depressing stuff saw me delve into history a bit today (although the delving was driven by wider research interests rather than an escape from the Teutonic version of neo-liberalism – which is at the extreme end of neo-liberalism – the idiot end!).

Which brings me to the title of today’s blog – Wir wollen Brot!

Here are some photos that were sourced from the (fabulous) German Bundesarchiv.

The first – Im Kampf gegen den Kältetod (the fight against hyperthermia) – was taken in Berlin (at the old Plaza – a Vaudeville Theatre) on March 7, 1947 and the caption “In Berlin hat die Polizei Ermittlungen angestellt, wo sich Menschen in Todesgefahr infolge Hunger und Kälte befinden. Die Zahl der Hilfsbedürftigen geht in die Tausende” reports that the Berlin police have found that there are thousands who are cold and hungry with no place to live.

This photo was taken in the “Düsseldorfer Hofgarten” on March 28, 1947 and captured some 80-100 thousand people protesting because they didn’t have enough food. The signs read (more or less) “we are hungry” and “We want bread”.

That was just 65 years ago.

Then reflect a bit more on history.

The Economic Consequences of the Peace (1919) was John Maynard Keynes’ commentary on Treaty of Versailles. He had been the British Treasury’s representative at the Versailles Conference.

The book demonstrated that Germany had been unfairly dealt with by the Treaty which had several consequences. Among them was the view that Britain (in particular) would go easy on Germany in the ensuing years (the “appeasement”) which amounted to Chamberlain turning a blind eye to the increasingly dangerous (and manic) Hitler. It also provided Hitler with a organising vehicle to unify the German people against the rest. World War 2 followed as a consequence.

Here is a long but very interesting quote from Chapter VI Europe after the Treaty, where Keynes was reflecting on the short-sightedness of Britain, France, Italy and the US (the “Council of Four”) in their approach to Germany (and Austria):

This chapter must be one of pessimism. The Treaty includes no provisions for the economic rehabilitation of Europe,-nothing to make the defeated Central Empires into good neighbors, nothing to stabilize the new States of Europe, nothing to reclaim Russia; nor does it promote in any way a compact of economic solidarity amongst the Allies themselves; no arrangement was reached at Paris for restoring the disordered finances of France and Italy, or to adjust the systems of the Old World and the New.

The Council of Four paid no attention to these issues, being preoccupied with others,-Clemenceau to crush the economic life of his enemy, Lloyd George to do a deal and bring home something which would pass muster for a week, the President to do nothing that was not just and right. It is an extraordinary fact that the fundamental economic problems of a Europe starving and disintegrating before their eyes, was the one question in which it was impossible to arouse the interest of the Four. Reparation was their main excursion into the economic field, and they settled it as a problem of theology, of polities, of electoral chicane, from every point of view except that of the economic future of the States whose destiny they were handling …

The essential facts of the situation … are expressed simply. Europe consists of the densest aggregation of population in the history of the world. This population is accustomed to a relatively high standard of life, in which, even now, some sections of it anticipate improvement rather than deterioration. In relation to other continents Europe is not self-sufficient; in particular it cannot feed Itself. Internally the population is not evenly distributed, but much of it is crowded into a relatively small number of dense industrial centers. This population secured for itself a livelihood before the war, without much margin of surplus, by means of a delicate and immensely complicated organization, of which the foundations were supported by coal, iron, transport, and an unbroken supply of imported food and raw materials from other continents. By the destruction of this organization and the interruption of the stream of supplies, a part of this population is deprived of its means of livelihood. Emigration is not open to the redundant surplus. For it would take years to transport them overseas, even, which is not the case, if countries could be found which were ready to receive them. The danger confronting us, therefore, is the rapid depression of the standard of life of the European populations to a point which will mean actual starvation for some (a point already reached in Russia and approximately reached in Austria). Men will not always die quietly. For starvation, which brings to some lethargy and a helpless despair, drives other temperaments to the nervous instability of hysteria and to a mad despair. And these in their distress may overturn the remnants of organization, and submerge civilization itself in their attempts to satisfy desperately the overwhelming needs of the individual. This is the danger against which all our resources and courage and idealism must now co-operate.

On the 13th May, 1919, Count Brockdorff-Rantzau addressed to the Peace Conference of the Allied and Associated Powers the Report of the German Economic Commission charged with the study of the effect of the conditions of Peace on the situation of the German population. “In the course of the last two generations,” they reported, “Germany has become transformed from an agricultural State to an industrial State. So long as she was an agricultural State, Germany could feed forty million inhabitants. As an industrial State she could insure the means of subsistence for a population of sixty-seven millions; and in 1913 the importation of foodstuffs amounted, in round figures, to twelve million tons. Before the war a total of fifteen million persons in Germany provided for their existence by foreign trade, navigation, and the use, directly or indirectly, of foreign raw material.” After rehearsing the main relevant provisions of the Peace Treaty the report continues: “After this diminution of her products, after the economic depression resulting from the loss of her colonies, her merchant fleet and her foreign investments, Germany will not he in a position to import from abroad an adequate quantity of raw material. An enormous part of German industry will, therefore, be condemned inevitably to destruction. The need of importing foodstuffs will increase considerably at the same time that the possibility of satisfying this demand is as greatly diminished. In a very short time, therefore, Germany will not be in a position to give bread and work to her numerous millions of inhabitants, who are prevented from earning their livelihood by navigation and trade. These persons should emigrate, but this is a material impossibility, all the more because many countries and the most important ones will oppose any German immigration. To put the Peace conditions into execution would logically involve, therefore, the loss of several millions of persons in Germany. This catastrophe would not be long in coming about, seeing that the health of the population has been broken down during the War by the Blockade, and during the Armistice by the aggravation of the Blockade of famine. No help, however great, or over however long a period it were continued, could prevent those deaths en masse.” “We do not know, and indeed we doubt,” the report concludes, “whether the Delegates of the Allied and. Associated Powers realize the inevitable consequences which will take place if Germany, an industrial State, very thickly populated, closely bound up with the economic system of the world, and under the necessity of importing enormous quantities of raw material and foodstuffs, suddenly finds herself pushed back to the phase of her development, which corresponds to her economic condition and the numbers of her population as they were half a century ago. Those who sign this Treaty will sign the death sentence of many millions of German men, women and children.”

Earlier, in Chapter 1, Keynes wrote “If the European Civil War is to end with France and Italy abusing their momentary victorious power to destroy Germany and Austria-Hungary now prostrate, they invite their own destruction also, being so deeply and inextricably intertwined with their victims by hidden psychic and economic bonds.”

The events that followed the Treaty are historically etched in our modern history. Two major events were directly related to the way the Council of Four treated Germany at Versailles.

First, the hyperinflation on Weimar Republic – which today dominates the German psyche – was the direct result of the onerous reparations and the carve up of territory which included major German productive capacity.

Very few people understand how the staggering Weimar hyperinflation occurred. They focus exclusively on the expansion of the money supply and so carry this over into the present day and think that if the ECB was to bailout all the nations by supporting their growth-inducing budget deficits there would be a recurrence of this price instability.

The reality is that the hyperinflation episode was not a result of the central bank expansion of its balance sheet (issuing more notes) – that was a symptom rather than a cause. Two points are clear. First, the Treaty of Versailles imposed unrealistic reparation obligations on Germany which forced it to “print money”. Second, the invasion of the Ruhr by Belgo-Franco troops after the war cut German’s export income.

There was a nice summary of this in an article today published in the Melbourne Age (November 23, 2011) – Germany picks the wrong war. The author (Saul Eslake) wrote:

Those hyper-inflations, and similar episodes in other countries occurred not simply or solely because central banks printed enormous quantities of money: but rather because they did so in order to maintain demand in circumstances where, for very different reasons, the supply side of their economies had been massively eroded.

In the case of Weimar Germany, the Reichsbank began printing money in order to pay the reparations imposed by the Treaty of Versailles. And those money-printing operations were dramatically stepped up after January 1923 when, after Germany failed to deliver one hundred thousand telegraph poles to France, 40,000 French and Belgian troops invaded and occupied the Ruhr Valley, Germany’s industrial heartland, dramatically curtailing Germany’s export income (and hence its capacity to earn the foreign exchange needed to pay reparations to France).

There is almost always a major loss of productive capacity involved prior to the inflationary event.

Please read my blog – Zimbabwe for hyperventilators 101 – for more discussion on this point.

On Zimbabwe, Eslake wrote that “The hyper-inflation experienced more recently in Robert Mugabe’s Zimbabwe resulted from his government’s printing of huge amounts of currency to pay for the continued activities of his government while simultaneously destroying the productive capacity of Zimbabwe’s agricultural sector by handing it over to his cronies.” Exactly.

And that “All of these situations are worlds away from that facing the euro zone today”:

Japan’s experience of the past 20 years demonstrates that it is actually very difficult to generate inflation by expanding the central bank’s balance sheet, even when that is an explicit objective, in circumstances where potential supply exceeds aggregate demand by a wide margin … There is no want of potential supply in Europe. Unemployment is stuck at 10 per cent. Twenty per cent of the euro zone’s industrial capacity lies idle.

For all I know, Wolfgang Schäuble who was born in 1942 may have been carried by his mother or father to one of those hunger demonstrations that cropped up all over Germany in the aftermath of the Second World War.

Fortunately, the World learned a lesson or two between the Treaty of Versailles and the immediate period after the Second World War ended. After the termination of the War, the victorious allies did not repeat the mistake of the Treaty of Versailles. Even after the devastation that Germany caused as a result of its misguided territorial ambitions and heinous ethnic policies, the Marshall Plan sought to build not destroy.

Interestingly, June 5, 1947 George Marshall announced the European Recovery Program (ERP) (which became known as the Marshall Plan) at Harvard University on June 5, 1947. So at least some sense was coming out of Harvard in those days.

The ERP “was intended to rebuild the economies and spirits of western Europe, primarily … the key to restoration of political stability lay in the revitalization of national economies”.

The victorious allies did not preach austerity although Germany had clearly lived well beyond its real resource limits during the War. They were faced with a massive destruction of public and private infrastructure and knew that a return to very fast economic growth was necessary to minimise the damage and contain it in historical time.

The upshot was a very progressive public spending campaign.

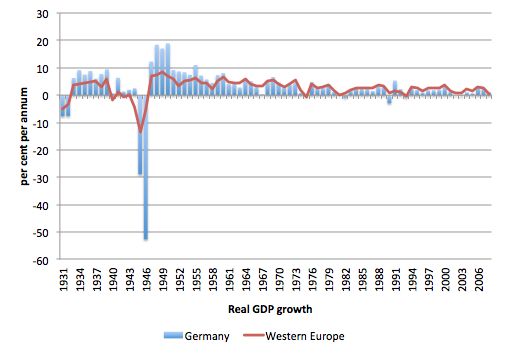

Between 1948 and 1952 Europe’s economic growth achieved its historical high. The late Angus Maddison maintained a wonderful Historical Database and the following graph uses that data.

It shows annual real GDP growth from 1931 to 2008 for Western Europe (red line) and Germany (blue columns) and the bounce-back after the War on the back of the Marshall Plan is clear. Other initiatives were also tried which might have helped but with the macroeconomic clout – the strong growth in aggregate demand – the growth could not have occurred.

Within a short time, poverty and hunger all but disappeared in Western Europe and this led to around 3 decades of sustained growth supported by strong fiscal activism. Between 1948 and 1973 (just before the OPEC oil shocks), per capita GDP rose by 5.8 per cent on average a year in Germany (and similar though lower amounts in other Western European nations).

I realise that there are major debates about the territorial ambitions of the Americans that might have motivated the Marshall Plan and, in particular, their anti-communist obsession. They are another story.

I certainly wouldn’t advocate giving Germany more control over nations in the EMU. But the ECB could clearly play the role of paymaster for the deficit-led growth boost. That is what the EMU needs more than anything. Then they can sort out the major defects in their monetary system – which I consider requires its eventual abandonment in favour of political union only.

Conclusion

Germans appear to have a very selective historical memory and have constructed certain events (the 1920s) in selective ways to reinforce the conservative neo-liberal ideology.

If the austerity bent they are insisting on continues more idle capacity will appear and they will be further undermine the future growth path of the region.

Ironically, by scaring off productive investment through austerity they actually increase the inflation risk in the future. While in the Weimar years the French and Belgians seized Germany’s industrial heartland and reduced the inflationary-room for growth, the current austerity is killing growth in productive capacity and so for a given nominal spending growth rate, the inflation risk becomes higher.

It is also clear that the austerity approach is not working to achieve their goals – however misguided those goals are. Budget deficits will rise as a result of the automatic stabilisers reacting to further declines in real GDP growth.

The only card they can play is the ECB and they should use the currency-issuing capacity to “fund” deficits in all nations commensurate with the existing private spending gap.

This would fast track domestic growth, increase world trade and would achieve reductions in budget deficits, rising exports, and significant reductions in unemployment.

The bond market traders would flood back into European tenders at low yields and the ECB could gently retire back into its conservative world.

If they don’t do that then as Saul Eslake notes:

Germany’s economic and political generals are re-fighting the wrong wars. In so doing, they are risking the whole European project, and more besides.

They should study the lessons of the two great European wars in the C20th and stop lying about what happened.

That is enough for today!

They can’t find the bazooka because it’s a panzerfaust and Michael Meister hid it up his own backside. I’m surprised he wasn’t blushing when they asked home where it was.

A period erased from economic history as usually told is Germany after the hyperinflation, before Hitler. What made it Springtime for Schicklegruber in Deutschland was not inflation but austerity, a mirror of today’s Bundesbank & ECB behavior.

Here is a quote on this that /L posted here a while ago, from Per Gunnar Berglund’s book Abolishing Unemployment

“The German Chancellor during the late Weimar republic, Heinrich Brüning, was the most obsessed by fiscal orthodoxy of all statesmen at the time. His fear of budget deficits made him pursue a policy of merciless austerity, which forced the German unemployment rate up to 40 percent. The increasingly desperate population came to view Hitler as “unsere letzte Hoffnung” – our last hope. A racy detail in this historical misery, is that Keynes met Brüning in Berlin 1932. The Chancellor had to face harsh criticism, but Brüning boldly declared that it would be folly to give up “a hundred yards from the finishing post”. But Brüning never reached the finishing post. Instead, he unrolled the red carpet for Hitler.”

I always find it instructive to do weather forecasts ‘in the long run’. In the long run there will be snow in the Sahara.

Economics should realise that it is doing weather forecasts for the economy.

Dear Bill

Germany isn’t the only country insisting on fiscal austerity. The Dutch, British and Finns are doing the same, although Britain is of course not part of the Eurozone.

The German trade surplus is now 5% of GDP. If other countries were to pursue the same policy of wage moderation, the German trade surplus would disappear and plunge the German economy in a recesssion. That’s the problem with mercantilism through wage moderation. You either end up giving your goods away or else you have to reverse course eventually in order to run a trade deficit and recoup the surplusses invested or lent abroad. It should be clear that demand stimulation through exports is a foolish policy, if only because, unlike internal demand stimulation, it can’t be practiced by all countries at the same time.

Regards. James

The solution that Bill advocates is a popular one, and I’m not impressed by it. Obviously the ECB will not go bust if it buys periphery debt which turns out to be worthless. But the important point is that if the periphery manages to sell the ECB a series of bum steers, that amounts to a subsidy by core countries of the periphery.

Core countries (and the periphery, come to that) DID NOT JOIN the EZ on the basis that they were going to have to subsidise other countries. To that extent I don’t blame Germans for sticking to the rules originally agreed to.

The EZ faces a number of options, all of them defective, as follows:

1. Bill’s “solution” is essentially to kick the can down the road. That is, give Greeks more money and hope they reform and become more competitive. Well that’s just a joke.

2. Continue imposing austerity on the periphery. That could lead to anarchy in some periphery countries.

3. Have some countries leave the EZ: possibly Germany and other core countries or possibly some periphery countries.

4. Go for a full blown fiscal union, like the US or UK. I just don’t see that working. The cultural and historical features of different regions of the US and UK are sufficiently strong that rich areas don’t mind subsidising poor areas. I don’t see that working in the EU.

Wasn’t the Marshall plan the perfect anti-MMT plan? European countries did not use their own currencies to rebuild, they used US dollars instead.

Ralph,

You’ve got that the wrong way around. Bill’s plan bails out the German and French banks and confirms the savings they’ve accumulated by running a vendor financing scheme in the periphery.

The periphery didn’t join a Eurozone expecting that Germany would run a persistent 5% GDP export surplus. They bought German battleships on the understanding that the Germans would holiday in the Islands with the proceeds – thus completing the monetary circuit, clearing the initial investment and allowing it all to start again.

It’s not just the liabilities that disappear on default. The assets do too. Any sort of bailout by the ECB allows both sides to keep their spoils.

Ralph: Following your logic through, I conclude that the Eurozone is fundamentally flawed and must change or break up. This is what Bill and many others argue. You have simply pointed out the fundamental flaw, which seems to be that in a currency union the rich regions MUST subsidize the poor regions, as you point out for the US and UK. In a true fiscal union, as in the US and UK, the support occurs by fiscal transfers, federal funds flow differentially to regions based on “need”. A fiscal European Union would require that same thing, by one mechanism or another. You state that this is not politically acceptable, nor was this envisioned in the construction of the Eurozone. Thus the fundamental flaw. The ECB buying Greek bonds is the only mechanism available for the transfer of funds in the current structure. It is no different from the transfer of funds that occurs in a federal monetary union. So, either you have it or you don’t, the mechanics don’t matter. So, the ECB buying bonds is not kicking the can down the road, only to delay a final collapse, it could be a sustainable mechanism for enabling the required fiscal transfers. If not allowed then breakup is inevitable by your logic. Regards, Jim Thomson

“If Britain is already meeting a larger percentage of its budget deficit by seigniorage than Germany did at the height of its hyperinflation, why is the pound now worth about as much on foreign exchange markets as it was nine years ago, under circumstances said to have driven the mark to a trillionth of its former value in the same period, and most of this in only two years? Meanwhile, the U.S. dollar has actually gotten stronger relative to other currencies since the policy was begun last year of massive “quantitative easing” (today’s euphemism for seigniorage). ”

http://www.prosperityagenda.us/node/200

Evans-Pritchard came to the same conclusion in his editorial following the Spanish election the other day:

“It Germany genuinely wishes to save Spain and Italy, it must allow EMU-wide reflation and mobilize the ECB as a lender of last resort to halt the bond crisis, since the EFSF rescue fund does not exist. To create a currency without such a backstop is criminally irresponsible. If this role is illegal under EU treaty law – and that is arguable – then EU treaties must be changed immediately. If Germany cannot accept this for understandable reasons of sovereignty or ideology, it should accept the implications and prepare an orderly break-up of monetary union. That is the only honourable course.”

That clearly spells out the dilemma for Merkel and Schäuble: They actually do not want to break up EMU, but they are also loath to let the ECB get the bazooka out. And while the latter arguably does have to do with economic ideology (including its historical evolution), the principal reason, at least as I see it, is to be found in domestic politics. Note that Merkel has her own party and coalition partner, the liberal party, to appease, both of which have considerable numbers of dissidents only held in check by party discipline (some call it extortion) and would most likely have gone into staunch euro-opposition long ago if they didn’t happen to be the parties in power. Very similar, incidentally, to the period of labour market reforms carried out by the social democrat/green government after 2003, which the same parties would have opposed fiercely had they come from the conservative-liberal block.

Now, Merkel has closely observed what that episode has done to the social democrats who collapsed to 23 percent of the vote in the last general elections and haven’t really recovered from that. Merkel and Schäuble are intend on avoiding this fate for the CDU if at all possible, and that, I believe, explains why they initially opposed every single step in the political reaction to the euro crisis since spring 2010, yet have always caved in eventually. Each time they took blame from their own constituency for that, but I daresay it was not the same as if they had gone along straight away with the Greek bailout, the first euro safety net, the extended safety net… I think there is a good chance that the same procedure will repeat with regard to the ECB as a lender of last resort.

I realise this must sound cynical, given the partly unnecessary economic hardship (as well as the unemployment and capital stock hysteresis that Bill points to) imposed on peripheral countries by artificially prolonging the crisis. In fact, this very criticism is being levelled at Merkel by the progressive left in Germany. But face it: Those are not the people that are going to vote for her in the next general election anyway. A vast majority of Germans is strictly opposed to both bail-outs and the ECB “printing money”, and for those people not to turn their back on the conservative party, you at least have to credibly put up a fight. And yes, Merkel’s approval ratings for handling the euro crisis have gone up lately as she opposed French push for a banking license for the EFSF and demanded more “structural reforms” in Greece or Italy. My guess, again, is that the German government will come round eventually – but not before the situation gets even worse. It might of course be too late when they do.

The alternative to fiscal transfers to the periphery is for Germany to run a fiscal deficit large enough to stimulate domestic demand and reverse the trade flow. But of course, that would violate the “Stability and Growth Pact”!

Do increased productivity in the western world pull up wages? We had many years of growth before the crises. Where is the wealth that will help us out?

The Germans should look at their own Volkswagen, which decided growth was the only way to deal with its high fixed costs and liabilities.

“Central banks exist to guarantee financial stability.”

And the best way to do that is to have a current account deficit = 0, gov’t debt = 0, private debt = 0, and have the currency printing entity have liabilities (medium of exchange) and no assets.

Please don’t judge us germans by the rubbish and reckless politics coming from our government. They are just puppets like everywhere else – and the puppeteers are working globally.

Bill Mitchell goes at great lengths to explain German economic thinking as it is represented by the German finance minister Schäuble. You can put German hypocrisy in much more simpler terms, it works like this:

The times are hard for German artisanry in seeking customers and orders. They often phone in the evening hours offering their excellent services to homeowners who are in our village more and more quite wealthy retirees and pensioners. This potential clientèle mainly lives on the public pension scheme fed by current employees’ contributions (on the decline) and by additional funds derived from the overall tax income completed by public debt. So according to the critics of public spending these pensioners and retirees live on BAD MONEY, they are a heavy burden on Germany’s financial stability and they represent Germany’s demographic crisis, too.

I often talk to these artisans about economics and politics in general and find them ranting and raving against public spending and debt in Germany. On the one hand these guys seek any money for their services regardless the source it comes from, on the other hand they draw their profit from those publicly and finally debt-funded incomes and condemn the tax man at the same time as a ruthless exploiter of their personal wealth. These guys are Minister Schäuble’s party electorate and he perfectly knows how to represent their blind-minded spirit.

The commentary is of course generally correct, but because it also leaves out certain details, and this makes it just another attempt of ideological manipulation of the readers.

There is a decisive difference between Germany 1945, and Greece, Irland, Portugal and Spain 2011. Today, there are MILLIONS of rich people in those states who have been profiting from their inept and corrupt governments, who have avoided paying taxes on their incredible incomes either completely, or at absurdly low taxrates, which their lobbyists and representatives have pushed through the parliaments, against the interest of country and the rest of the people.

You see, Paul Krugman’s “We are the 99%” is not just a phrase! When you look at the statistics you can easily find that the assets of the 1% are far bigger than the government debt of the countries concerned.

Not mentioning such little details says a lot about the motive behind your “alternative economic thinking”, as you choose to call it.

Dear DrLecter (at 2011/11/26 at 9:50)

From what you wrote, I would conclude that you have not read one of my academic works (journal articles and books) over the years nor many of my blogs.

Perhaps you would like to outline – in some detail – what you think my “motive” and “ideological manipulation” encompasses. Spell it out rather than generalise.

One cannot include one’s world view and every known fact that relates to it in each blog – they are long enough as it is.

best wishes

bill

It strikes me that the financial markets’ concern for the Euro as a stable currency is right at the root of the whole problem, both in EU and US — the financial markets have been allowed to become far too important a factor in the capital system, a place for the wealthy to run and hide their money rather than put it at some well-evaluated and reasonable risk ensconced in a development and production environment. Our whole world needs to minimize the unproductive capital markets and redirect capital flows into truly productive activity.

@bill

> The member states in the EMU cannot spend with funding

should be “without funding”?

Dear viosz (at 2011/12/01 at 6:51)

Thanks very much. I appreciate the scrutiny.

I have fixed it now.

best wishes

bill

Great article.

For the reasons of the German gov acting this way I agree with @Dagmar Brandt above, most Germans don’t have a clue about economics (me included) and German media, public or gov, alltogether supporting austerity for other states to “recover”, treating other nations like households.

So German people feel they earned the money they got from all the massive euro zone exports, they won the European competition (as the Euro zone was designed to be competitive) and don’t understand why other nations don’t pay back their debt by taxing the rich or selling their islands as their neighbour would have to sell it’s car or house to the bank to pay his debt. This is my personal experience from local discussions.