As part of a another current project, which I will have more to say about…

Ratings agencies and higher interest rates

On Friday, April 24, 2009 there was a story in the Australian entitled Deficit spike may lift rates as Government considers $300bn debt blowout which introduced the next step in the neo-liberal fight to retain control of the policy debate – the dreaded ratings agencies. Accordingly, the Government spending (wait for it) … “blows out the deficit” and this will “jeopardise Australia’s triple-A credit rating, leading to higher interest rates.” So if you cannot win the “crowding out” battle to justify an attack on deficit spending its time to wheel out those credit rating agencies to scare the children of our land. As you will read this sort of reasoning is nonsensical in the extreme.

The journalist David Uren claims:

Analysts are forecasting debt levels of $300 billion, and warn that unchecked borrowings would jeopardise Australia’s triple-A credit rating, leading to higher interest rates.

A combination of record deficits and a massive surge in debt repayments will force the Treasury to raise more than $140billion between now and June 2011, testing market limits

First, who are these analysts and are they “objective”? More on this later.

Second, statements like “record deficits” are unhelpful. We always compare the size of these things with some scale parameter to give them some correspondence with past outcomes. So professional economists will never just talk about the nominal value but compare it to GDP. At present the projected deficit of around $50 billion in 2009-10 will be around 2 per cent of GDP. This is dwarfed by the 3.3 per cent of GDP deficit in 1982-83 (the last John Howard budget) as the economy dealt with the major 1982 recession, and then the 3.0 per cent of GDP deficit in 1991-92; the 4.1 per cent of GDP deficit in 1992-93; and the 4.0 per cent of GDP deficit in 1993-94; and the 2.9 per cent of GDP deficit in 1994-95 as the economy struggled to get out of that recession.

Of-course, I am just citing the data to question the economic accuracy of the reporting rather than suggesting that the size of the deficit is something we need to worry about. You might like to read or re-read my blog – How large should the deficit be? – where I demonstrate why it is meaningless and stupid to concentrate on the actual size of the deficit whether you are talking about it in absolute terms or as a percent of GDP. That should never be a focus of concern. Governments must concentrate on the spending gap and make sure they close it as fast as they can to prevent the damaging rise in unemployment.

Third, the Government is not being forced to raise any revenue at all in relation to the net spending it is engaging in on our behalf to address the spending gap. The fact that they are issuing public debt is voluntary and is not necessary to “finance” its spending. The Australian government is the monopoly issuer of the $AUD and can spend it at will without any prior need to “raise revenue”. The fact that the Treasury is simultaneously issuing debt owes more to monetary policy ambitions (maintaining the RBA cash rate target) than anything else. It is also driven by an ideological viewpoint – see my blog Will we really pay higher interest rates? – that all Government net spending should be fully covered by raising the same amount fully “from the private debt markets”. That is purely a religious act – it is certainly not grounded in any reasonable understanding of the options that the sovereign issuer of the currency has at it disposal.

So it would be better to just have some accurate reporting based on how the system actually operates.

Anyway, the Government (voluntarily) has a $200 billion “borrowing ceiling” and they are now planning to exceed that. Of-course, they have to if they insist on their voluntary obsession with matching net spending $-for-$ with market borrowing. Note I use the word matching rather than financing. It is just a matching transaction.

And those analysts! Well it turns out to be an employee of the notorious credit rating agency Standard and Poors who have a vested interest in ramping up the public debate so they get more business. More about this later!

The journalist reports that the S&P employee said the agency “retained confidence in the Government and expected it to outline in next month’s budget its plan for returning to surplus, but cautioned that the borrowing could not continue indefinitely.”

The employee is then quoted as saying:

If debt levels continue to mount at the pace they are likely to over the near term, that is something we would be taking a look at; however, we are comfortable with the near-term debt profile and operating position.

Another investment bank (USB) economist was quoted in the article as saying: “If they …[Australian Government] … have to add another $25 billion a year to their issuance program, it would have a material impact forcing up yields.” This is implying that the investor support will decline and a premium will be imposed via the auction process. Apparently, Britain and Germany are now suffering a declining “investor support”.

In the current IMF forecasts, they are claiming we will hit a snag in raising money from international markets unless we preserve the credit rating. The S&P employee was quoted as saying in this regard to ability to generate export earnings relative to foreign debt, that:

… We are confident that this Government, which has a history of fiscal conservatism in opposition and in government to be running modest surpluses over the medium term with low debt levels. We have a comfort that, on both sides of parliament, there is a strong fiscal conservatism, and we think that Australia will get back to surplus over the medium term and that is what keeps Australia’s (AAA) rating stable.

It is almost beyond belief that these characters are paid a salary as analysts to say and think this sort of nonsense. To understand why it is so, we digress to consider Japan.

Japan and Moody’s

In November 1998, the day after the Japanese Government announced a large-scale fiscal stimulus to its ailing economy, Moody’s Investors Service began the first of a series of downgradings of the Japanese Government’s yen-denominated bonds, by taking the Aaa (triple A) rating away. The next major Moody’s downgrade occurred on September 8, 2000.

Then, in December 2001, Moody’s further downgraded the Japan Governments yen-denominated bond rating to Aa3 from Aa2. On May 31, 2002, Moody’s Investors Service cut Japan’s long-term credit rating by a further two grades to A2, or below that given to Botswana, Chile and Hungary.

In a statement at the time, Moody’s said that its decision “reflects the conclusion that the Japanese government’s current and anticipated economic policies will be insufficient to prevent continued deterioration in Japan’s domestic debt position … Japan’s general government indebtedness, however measured, will approach levels unprecedented in the postwar era in the developed world, and as such Japan will be entering ‘uncharted territory’.”

The then Japanese Finance Minister responded (with some foresight): “They’re doing it for business. Just because they do such things we won’t change our policies … The market doesn’t seem to be paying attention.” Indeed, the Government continued to have no problems finding buyers for their debt, which is all yen-denominated and sold mainly to domestic investors.

In the New York Times the logic of the rating was questioned:

How … could a country that receives foreign aid from Japan have a better rating than Japan itself? Japan, with an economy almost 1,000 times the size of Botswana’s, has the world’s largest foreign reserves, $446 billion; the world’s largest domestic savings, $11.4 trillion; and about $1 trillion in overseas investments. And 95 percent of the debt is held by Japanese people …

Former Moody’s President, John Bohn Jr. had in 1995 claimed that: “We’re in the integrity business: People pay us to be objective, to be independent and to forcefully tell it like it is.” (Reference: Ratings Trouble, Institutional Investor, October 1995: 245).

How do these agencies approach the rating of sovereign debt? Moody’s defines a rating is “an independent opinion on the future ability and legal obligation of an issuer of debt to make timely payments of principal and interest on a specific fixed-income security”. Similarly, for S&P “a credit rating is S&Ps opinion of the general creditworthiness of an obligor, or the creditworthiness of a an obligor with respect to a particular debt security or other financial obligation, based on relevant risk factors”.

The agencies continually claim that they are providing an indicator of the “probability that the issuer will default on the security over its life…” So when considering sovereign debt as opposed to corporate debt, the agencies are suggesting that as the public debt to GDP ratio rises, the risk that the government will become insolvent rises. And their logic must be that default follows sovereign insolvency even when the sovereign debt is denominated in the government’s own currency. It doesn’t take long to realise that this logic is no logic.

Rating sovereign debt according to default risk is nonsensical. While Japan’s economy was struggling at the time, the default risk on yen-denominated sovereign debt was nil given that the yen is a floating exchange rate.

Once we understand how a sovereign government operates with respect to the monetary system this point become obvious.

First, when a particular government bond matures (that is, becomes due for repayment) the Government of Japan would simply credit the bank account of the holder with the principle and interest and cancel the accounting record of that debt instrument. Simple as that. The banking reserves would rise by that amount and the wealth of the private investor would change in mix from bond to bank deposit.

Second, the massive fiscal deficits that the Japanese Government has run since the 1990s just work in the same way – adding reserves on a daily basis to the banking system (as people spend the yen and deposit them back into bank accounts etc). The bond issues are designed to give the private sector an interest-bearing financial asset to replace the non-interest earning bank reserves. The way the Bank of Japan (BOJ) has kept the interest rate in Japan at virtually zero for years now is that they do not issue debt volume of debt to match the reserve-add of the deficit spending. That is, they leave just enough excess reserves in the cash system overnight each day to force the interbank market to compete the rate down to zero. This is a very clever way of ensuring that the longer rates (the so-called investment rates) are as low as they can be.

Third, what if the Japanese Government decided it didn’t want to issue any more debt but still ran the deficits? The net spending would still occur – day by day – and provide stimulus to the economy. But the liquidity effects would just remain in the excess banking reserves and force the private sector to hold the new net financial assets pouring in each day via the deficits in the form of reserves rather than interest-bearing bonds. The other angle on this that is often overlooked is that the bond holdings of the private sector also constitute an income source – that is, the government interest payments on its outstanding debt constitute another avenue for stimulus. So when the Government retires debt it reduces private incomes.

The Japanese Government is very sophisticated and knew that Government debt was seen as a safe haven during its decade or more of volatile economic times and also realised that the steady and predictable income flow derived by the private sector holding the public debt was a source of security and a positive influence on growth.

So any notion that a government that is running large fiscal deficits and also issuing debt for monetary policy reasons or in the Japanese case (given they have zero short-term interest rates anyway) for risk reduction purposes, might be a risk is ridiculous.

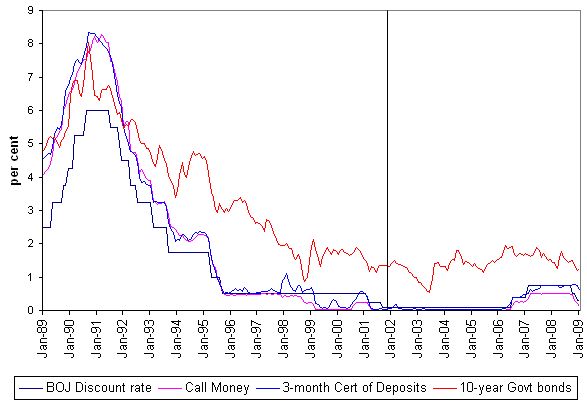

The following graph is a long time-series look at the major Japanese money market interest rates. You will see that over the period that Moody’s was playing stupid downgrading games with the Japanese Government that no interest rate effects were detected. The vertical black line is December 2001.

Note that this analysis does not consider foreign-currency denominated public debt which is subject to exchange rate exposure and clearly tells us that a sovereign government should never issue debt in any currency other than its own. But in the Japanese case, the ratings agencies clearly stated they were rating default risk not currency risk.

For Australia, foreign holders of our public debt will clearly face exchange rate (or currency) risk. But that is not related to the decision of the Government to net spend unless you bring the old furphy out that these amorphous hedge funds out there will mark a currency down if a Government borrows to much. That is possible but unlikely. Suggesting that this will push up interest rates (to provide some cover for the currency risk) assumes that the Government is stupid enough to keep borrowing from markets that want to impose this type of penalty.

If that was the case, then you will understand by now that this behaviour is entirely voluntary given they do not have to “finance their deficits”. So it would not be the deficits that were pushing the rates up but the stupidity of the neo-liberal constrained Government policy whereby it has to match net spending with debt issues ($-for-$). Purely voluntary – totally unnecessary – and very stupid.

Why do flexible exchange rates matter?

Some progressive economists think the answer to our problems – global financial instability – hedge funds etc – is to return to the old Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates. That is definitely not the answer. For a sovereign government spending in its own flexible exchange rate currency is simple – credit bank accounts which add to reserves. The Government does not promise that these reserves are convertible into anything else.

Under the fixed exchange rate system (or a gold standard) the Government is actually promising to exchange the domestic currency on issue for say gold or foreign currency reserves. In those cases, the Government is not sovereign in its own currency and can run out of foreign exchange reserves if there is a run on its own currency.

Ratings agencies and corruption

While the ratings agencies hold a strong position in financial markets, recent history has uncovered their problematic ways.

The three leading agencies are Standard & Poors (the oldest dating back to 1860), Moodys and Fitch (both of which began life in the early C20). All three were instrumental in the early days of the railroad companies and helped them borrow massive amounts. Of-course, many of the railroad companies went broke. So the problems with the ratings system has been around for a long time.

But they continue to hold a strong position. For a product (company) trying to raise funds, it is crucial to get a triple-A rating then the large institutional investors like superannuation funds and insurance companies can purchase the assets (being prevented by their charters from taking lower rated paper). So there has always been a massive incentive for firms to work in tandem with the ratings agencies.

Further, under the Bank of International Settlements Basel II framework, which imposes capital requirements on commercial banks, highly rated loans score more highly and provide strong advantages for the banks.

The ratings agencies, however make well-documented mistakes, which have been monumental in impact and for which they have largely escaped accountability. Classic failures are the Orange County and Enron disasters where the agencies were clearly incompetent. As we show next, while the earlier “mistakes” suggested faulty rating models or methods, the later sub-prime debacle revealed endemic corruption.

In retreat, the ratings agencies either said that their mistakes were based on corporate fraud – their Enron defence or that investors should use other information in addition to their ratings. But they admitted, for example, to the UK Treasury Select Committee that a great many investors without significant intelligence capacities rely on them to guide their investments.

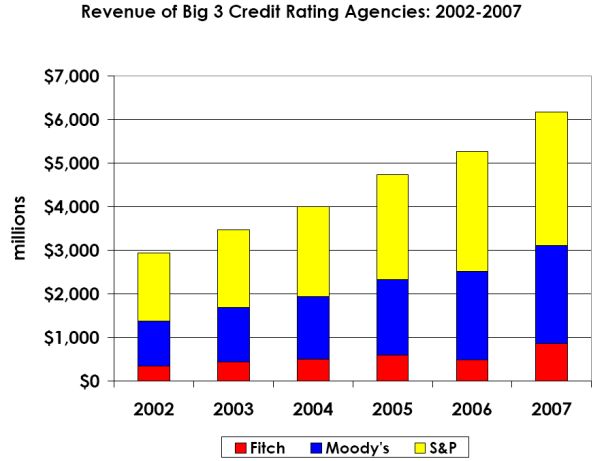

But it gets worse. During the boom years leading up to the beginning of this crisis the agencies also boomed. The following graph shows the growth in revenue of the three largest agencies over the debt binge period.

You may also want to look at the share prices of McGraw-Hill (owner of Standard & Poors) and Moody’s over this period (just click return on your browser to come back to the blog). As you will see – both agencies boomed and these “analysts” were paid very handsomely for their work.

But the revenue boom of the agencies was funded by the companies that they were rating. Conflict of interest? No, straight out corruption.

In Who’s to Blame for the Economy? Rating Agencies, Dan Freed writes:

Though the ratings agencies held themselves up as independent arbiters of credit quality, it appears they actually just pimped themselves out to the issuers, who paid them for their ratings. As The New York Times reported in December, when Countrywide Financial complained to Moody’s that it didn’t like a rating on a security it issued, Moody’s changed it a day later without any new information coming to light. A Moody’s spokesman denies the agency has ever done this, the Times reported.

But when the executives and “analysts” of the major agencies were subjected to the “blow torch” by the The US Congress Oversight Committee hearings into this matter, some plaintiff admissions emerged. Employees (those “analysts”) of leading agencies admitted taking “money for ratings”. See also this page further information and links to this.

So nothing they say should really be believed at any level. They share the same problems that the auditing profession face. Their fortunes depend on how they rate/audit the companies that are hiring them or using them as “objective” indicators of corporate quality. It is a no-brainer.

The best thing the governments could do would be to regulate the ratings agencies out of existence or legislate that they had to pay (including their analysts) cash for mistakes. Better the former – just get rid of them and force the investment community to invest some real effort into sound financial product appraisal.

Conclusion

The basic point of this blog is to disabuse readers of the neo-liberal view that: (a) public debt issuance will drive up interest rates. They will help the central bank maintain target rates (which could more easily be done by just paying a return on excess reserves). The debt issuance is an entirely voluntary act by our Federal government which does not have to finance its net spending; and (b) the ratings agencies are a blight on our economic landscape.

Digression: Another gem of journalistic boganity

In today’s paper, Fairfax journalist Paul Daley wrote:

… the [Australian] Government … is spending tens of billions of dollars it does not have to prop up the economy … while foreshadowing its willingness to dole out more unthinkable sums on a national broadband network … With unemployment climbing, Australians are concerned about personal circumstance. But they are not so self-absorbed they are immune to worrying about their country’s future finances … Householders understand the simple equation that borrowed money must be repaid. As it is with household shopping, the mortgage and other loans, so it is with the nation’s finances.

It doesn’t get much worse than that. The Australian government has as many Australian dollars as it wants! It is the monopoly issuer. The sovereign government which issues the currency is totally different to a household which uses the currency. The latter faces a budget constraint and has to pay back its debts. The former has no budget constraint can pay back any debt it issues without compromising its spending capacity. A sovereign government has no financial constraint, which is not the same thing as saying they face no spending constraints. But these are voluntarily imposed; or political; or real (there may be no idle resources).

In the earlier article I criticised, the journalist was reporting what others were saying. It was not an opinion piece. That doesn’t reduce the author’s responsibility to balance the discussion which in that case he did not. He used macroeconomic concepts in a totally inapplicable way and reinforced them with commentary from so-called experts who clearly demonstrate vested interests (working in the corporate world).

But Daley’s article is an opinion piece. In that case, why do these journalists, who clearly don’t understand the complexity of the modern monetary system, continue to write this nonsense (as their “opinion”) in the full knowledge their message is being indelibly etched in the minds of their, also untrained readers. In reality, they are just perpetuating the neo-liberal fabrications about the role of government and public goods provision and that is their intent or they are too ignorant to know better. Either way, it is unacceptable. Lucky I didn’t pay for the newpaper!

Etymology of boganity

An international reader has asked me about my bogan register and the low art of boganity, which, aptly, rhymes with profanity.

Boganity is the behaviour exhibited by bogans. Here is the definition from Wikipedia of the noun bogan!

While this is often interpreted in “class” terms – haves and have-nots – I use the term more narrowly to represent wanton ignorance while in in a position of power – which should be taken to mean a journalist with a typewriter and massive daily circulation communicating with a largely uninformed public.

You are absolutely spot on . I wish you were telling it like it is on the American scene. Well you are due to the strpng similarities of the two systems. Warren and others are trying to talk some sense via Warren’s website and afew others, but you have a way of expressing it so clearly and logically that even the “unschooled” should be able to “get it”. What is so difficult about understanding that a government, and more to the point a government that is the sovereign issuer of its own non convertible currency, is NOT run the the same way as a household or a business and does not have the same constraints on its spending?

Weel done Billy!

I was thinking as I read that government should just ignore the ratings agencies and get on with doing what it has to do but regulating them out of existence would be better (and more satisfying).

One problem for a government wishing to spend whatever amount it truly feels it will take is that the ratings agencies voices are heard very loudly around election time, repeated by journalists everywhere, panicking voters about “massive government debt” and giving the opposition ammunition to use.

Thanks Barton. I appreciate your feedback. I do try to take an international view where I can. But the Internet is global and a lot of people in the US are reading my blog (I can tell via IP addresses on the logs). A way of spreading the message is to refer to an post that you might like here when you are making a comment somewhere else. That instantly notifies people who haunt that blog about my work.

And as to your last point … it does amaze me that the neo-classical text book macroeconomics persists when applied to the sovereign issuer of its own non convertible currency. I think it is that economics is not learned by many people and they think it is more complex than what it actually is. So these witchdoctors of so-called science can just make up whatever suits their ideological purpose and people believe them.

Anyway, best wishes

bill

In about 12-18 months as our next national election approaches, these credit rating analysts will be in the media every day talking about “risk” etc. Problem is people will believe them even though they hold the debt which is wealth to them and generates a better income stream than if they just left the “cash” in the banking system as deposits (and excess reserves). Stupidity will rule and you can bet that the Opposition leader whoever it is by then will be making the most of it. Humans really lead a low brow existence at times.

Considering that the majority (probably all) first year economics courses teach students a bastardised version of the truth it is little wonder that the journo’s get it wrong.

The simple solution is to change the way 1st year macro courses are taught at universities. Unfortunately nobody has the ticker to do it.

Leaving it until 2nd or 3rd year before introducing how a modern money economy operates is merely closing the gate after the horse has bolted.

Cheers

Alan.

Hi bill

i’ve just discovered your blog, and reading about how the real monetary system works is very enlightening, to say the least. ofcourse this type of info will rarely, if ever, be reported in the msm,

i have a quick quesiton re something you said in this piece. You said that soveriegn govts. don’t have financial restraints as distinct from spending restraints…..now reading on your previous blog posts i had assumed the ability to print money and issue the naitonal currency as a given to having NO spending constraints. can i assume that govts. DO have spending constraints, if so what are they ? also, why do they persist in issuing debt and paying a % of gdp annually in paying the interest on that debt if it’s gesture economics.

Also, would you say it is healthier for a country to have the bulk of it’s debt issuance ‘owned’ by the domestic populace i.e via pension funds. Or is who owns the debt irrelevant so long as it can issue debt it’s own currency.

Dear Alan

You are correct – the damage is done. Randy Wray and I are currently writing a modern monetary text book for introductory economics which we hope is the first step in filling that void. But trying to get it adopted by lecturers will be the next challenge.

best wishes

bill

Dear Tricky

Thanks for your question. When I distinguished between financial and spending constraints I was referring to the following. It is clear that a sovereign government (one that issues its own non-convertible currency) has no financial constraints. It does not have to “finance” its own spending and the funds that it receives from taxpayers and those who buy its debt ultimately come from itself via government spending. That is absolutely the case.

By the way, the “printing money” characterisation is not very sound. It is a neo-liberal construction and usually used in a pejorative sense implying some mad government in a basement flooding the economy with ever increasing amounts of paper which people wheel around in wheelbarrows to buy a loaf of bread as inflation accelerates out of control! Governments do not spend by printing money. All spending is done via crediting reserves in the banking system irrespective of whether it is “accompanied” by tax collections, bond issues or a solar eclipse!

Then we have to ask: what level of net spending (deficits) should it engage in? Then you confront the spending constraints. First, it is clear there are political (not economic) constraints – media perception; the myopia and ignorance of the Government and its advisors etc. Second, there are economic (real) constraints imposed by how much is available for sale. The Government can theoretically spend infinitely from a financial perspective but there is only so much real goods and services available to buy. So the Government clearly can purchase whatever is available for sale at any point in time. Attempting to expand nominal spending beyond that real capacity will be inflationary. But then by that time you already would have full employment so why would they be stupid enough to do that.

And the best place to start is for the Government to use this fiscal capacity to by up all the labour resources that are currently for sale (the unemployed) at a minimum wage and use that labour force for productive purposes – including the development of a new green workforce.

Why they continue issuing debt is covered in earlier blogs – for example the Deficit 101 series – Part 3 specifically covers that question. Also more recently blogs such as Will we be paying higher interest rates? also discusses the political reasons. Apart from monetary policy considerations (interest-rate target maintenance) all the other reasons they continue to issue debt are voluntary. Further, I will write a blog soon about why the Sydney Futures Exchange lobbied the Government in 2001-02 to continue to issue government debt despite the fact the Federal Government was running massive surpluses. That is an interesting story about corporate welfare and is telling in its conclusion.

I don’t know whether “healthy” is a term I would use to describe who owned government debt. Clearly, domestic debt holders have no exchange rate (currency) risk and the Government could say it is providing wealth to its own citizens (financing the accumulation of saving by running deficits). But that might be a bit xenophobic. The key is the last point – a sovereign government should never issue debt in a foreign currency – then it loses its sovereignty with respect to capacity to pay back and it could “run out of funds” and become “insolvent” with respect to that debt.

best wishes

bill

bill

thanks for your reply. one final question if i may…if the real spending constraints are what is available for sale. would that be measured as a nations gdp. so when a country talks about running a deficit at say, 80% of gdp, is it spending less than what is available for sale in the economy ? And what of japan’s deficit, at one point 175% of gdp. that clearly wasn’t inflationary. Or am i confusing matters and using the wrong metrics.

hi bill

i have made an error in my figures, i was confusing debt targets with deficits. so japans debt was 175% of gdp not it’s deficit. is that more accurate ?

Dear Tricky

If a country did have a budget deficit equal to 80 per cent of GDP then the remaining 20 per cent would be non-government spending (either consumption, net exports or investment). That would be a very strange economy. At present, even with the expansion going on, Australia’s federal deficit is around 1.5 to 2 per cent of GDP. It should be much more (over 5 to 6 per cent) given the spending gap that is present and getting worse.

best wishes

bill