Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

Saturday quiz – December 31, 2011 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for yesterday’s quiz. The information provided should help you understand the reasoning behind the answers. If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

The government has two macroeconomic policy arms available – fiscal and monetary policy. However, it only has control over monetary policy.

The answer is True.

First, this question relies on an understanding that the treasury and central bank are both part of the consolidated government sector. Please read my blog – The consolidated government – treasury and central bank – for more discussion on this point.

In terms of monetary policy, the fundamental principles that arise in a fiat monetary system are as follows.

- The central bank sets the short-term interest rate based on its policy aspirations.

- Government spending is independent of borrowing which the latter best thought of as coming after spending.

- Government spending provides the net financial assets (bank reserves) which ultimately represent the funds used by the non-government agents to purchase the debt.

- Budget deficits put downward pressure on interest rates contrary to the myths that appear in macroeconomic textbooks about ‘crowding out’.

- The “penalty for not borrowing” is that the interest rate will fall to the bottom of the “corridor” prevailing in the country which may be zero if the central bank does not offer a return on reserves.

- Government debt-issuance is a “monetary policy” operation rather than being intrinsic to fiscal policy, although in a modern monetary paradigm the distinctions between monetary and fiscal policy as traditionally defined are moot.

Accordingly, debt is issued as an interest-maintenance strategy by the central bank. It has no correspondence with any need to fund government spending. Debt might also be issued if the government wants the private sector to have less purchasing power.

Further, the idea that governments would simply get the central bank to “monetise” treasury debt (which is seen orthodox economists as the alternative “financing” method for government spending) is highly misleading. Debt monetisation is usually referred to as a process whereby the central bank buys government bonds directly from the treasury.

In other words, the national government borrows money from the central bank rather than the public. Debt monetisation is the process usually implied when a government is said to be printing money. Debt monetisation, all else equal, is said to increase the money supply and can lead to severe inflation.

However, as long as the central bank has a mandate to maintain a target short-term interest rate, the size of its purchases and sales of government debt are not discretionary. Once the central bank sets a short-term interest rate target, its portfolio of government securities changes only because of the transactions that are required to support the target interest rate.

The central bank’s lack of control over the quantity of reserves underscores the impossibility of debt monetisation. The central bank is unable to monetise the federal debt by purchasing government securities at will because to do so would cause the short-term target rate to fall to zero or to the support rate. If the central bank purchased securities directly from the treasury and the treasury then spent the money, its expenditures would be excess reserves in the banking system. The central bank would be forced to sell an equal amount of securities to support the target interest rate.

The central bank would act only as an intermediary. The central bank would be buying securities from the treasury and selling them to the public. No monetisation would occur.

However, the central bank may agree to pay the short-term interest rate to banks who hold excess overnight reserves. This would eliminate the need by the commercial banks to access the interbank market to get rid of any excess reserves and would allow the central bank to maintain its target interest rate without issuing debt.

So the private sector cannot directly influence the central bank’s capacity to set interest rates. Clearly the central bank considers developments in the private sector but that is a different matter.

However, the private sector does ultimately determine the budget balance associated with fiscal policy (including how much tax revenue the government receives for a given set of tax rates and how much spending the government will provide for a given welfare structure).

The budget balance has two conceptual components. First, the part that is associated with the chosen (discretionary) fiscal stance of the government independent of cyclical factors. So this component is chosen by the government.

Second, the cyclical component which refer to the automatic stabilisers that operate in a counter-cyclical fashion. When economic growth is strong, tax revenue improves given it is typically tied to income generation in some way. Further, most governments provide transfer payment relief to workers (unemployment benefits) and this decreases during growth.

In times of economic decline, the automatic stabilisers work in the opposite direction and push the budget balance towards deficit, into deficit, or into a larger deficit. These automatic movements in aggregate demand play an important counter-cyclical attenuating role. So when GDP is declining due to falling aggregate demand, the automatic stabilisers work to add demand (falling taxes and rising welfare payments).

When GDP growth is rising, the automatic stabilisers start to pull demand back as the economy adjusts (rising taxes and falling welfare payments).

The cyclical component is not insignificant and if the swings in private spending are significant then there will be significant swings in the budget balance.

The importance of this component is that the government cannot reliably target a particular deficit outcome with any certainty. This is why adherence to fiscal rules are fraught and normally lead to pro-cyclical fiscal policy which is usually undesirable, especially when the economy is in recession.

While the short-term interest rate is exogenously set by the central bank, economists consider the budget outcome to be endogenous – that is, it is determined by private spending (saving) decisions. The government can set its discretionary net spending at some target to target a particular budget deficit outcome but it cannot control private spending fluctuations which will ultimately determine the final actual budget balance.

So the best answer is true.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Saturday Quiz – May 1, 2010 – answers and discussion

- Understanding central bank operations

- Building bank reserves will not expand credit

- Building bank reserves is not inflationary

- Deficit spending 101 – Part 1

- Deficit spending 101 – Part 2

- Deficit spending 101 – Part 3

- A modern monetary theory lullaby

- Saturday Quiz – April 24, 2010 – answers and discussion

- The dreaded NAIRU is still about!

- Structural deficits – the great con job!

- Structural deficits and automatic stabilisers

- Another economics department to close

Question 2:

Americans enjoy a higher material standard of living as a result of the Chinese holdings of US government debt.

The answer is True.

We are considering the macroeconomic outcomes only in this question. We might have concerns about the distributional consequences within the US that might arise from an on-going external deficit – that is that some might benefit while others will be losing jobs as manufacturing heads to China. But when we think in macroeconomic terms (which is mostly the case in this blog) we are dealing with aggregates and so the distributional questions, while very important, are abstracted from.

That qualification also has to be tempered by the important insights that progressive economists such as Michal Kalecki who showed how the distribution of income impacts on aggregate demand. Please read my blog – Michal Kalecki – The Political Aspects of Full Employment – for more discussion on this point.

But with those caveats in mind here is the explanation.

First, China can only do what the Americans and everyone else it trades with allow them to do. They cannot sell a penny’s worth of output in USD and therefore accumulate the USD which they then use to buy US treasury bonds if the US citizens didn’t buy their stuff. Presumably, people buy imported goods made in China instead of locally-made goods (which are more expensive) because they perceive it is their best interests to do so.

There is often a curious inconsistency among those who advocated free markets. They hate government involvement in the economy yet propose complex regulative structures (for example, tariffs) which would increase government control on resource allocation and, not to mention it, force citizens (against their will) to purchase goods and services they reject in an open comparison (on price and whatever other characteristics).

Many economists do not fully understand how to interpret the balance of payments in a fiat monetary system. For example, most will associate the rise in the current account deficit (exports less than imports plus net invisibles) with an outflow of capital. They then argue that the only way the US (if we use it as an example) can counter this is if US financial institutions borrow from abroad.

They then assume that this is a problem because it means, allegedly, that the US nation is “living beyond its means”. It it true that the higher the level of US foreign debt, the more its economy becomes linked to changing conditions in international credit markets. But the way this situation is usually constructed is dubious.

First, exports are a cost – a nation has to give something real to foreigners that it we could use domestically – so there is an opportunity cost involved in exports.

Second, imports are a benefit – they represent foreigners giving a nation something real that they could use themselves but which the local economy will benefit from having. The opportunity cost is all theirs!

Thus, on balance, if a nation can persuade foreigners to send more ships filled with things than it has to send in return (net export deficit) then that is a net benefit to the local economy. I am abstracting from all the arguments (valid mostly!) that says we cannot measure welfare in a material way. I know all the arguments that support that position and largely agree with them.

So how can we have a situation where foreigners are giving up more real things than they get from the local economy (in a macroeconomic sense)? The answer lies in the fact that the local nation’s current account deficit “finances” the desire of foreigners to accumulate net financial claims denominated in $AUDs.

Think about that carefully. The standard conception is exactly the opposite – that the foreigners finance the local economy’s profligate spending patterns.

In fact, the local trade deficit allows the foreigners to accumulate these financial assets (claims on the local economy). The local economy gains in real terms – more ships full coming in than leave! – and foreigners achieve their desired financial portfolio. So in general that seems like a good outcome for all.

The problem is that if the foreigners change their desire to accumulate financial assets in the local currency then they will become unwilling to allow the “real terms of trade” (ships going and coming with real things) to remain in the local nation’s favour. Then the local economy has to adjust its export and import behaviour accordingly. If this transition is sudden then some disruptions can occur. In general, these adjustments are not sudden.

So if you understand this then you will be able to appreciate the following juxtaposition:

- Neo-liberal myth: US consumers have to borrow $billions from foreigners to keep consuming.

- MMT reality: US consumers are funding $billions in foreign savings (accumulation of $US-denominated financial assets by foreigners).

Here is a transactional account of how this works which starts off with a US citizen buying a Chinese product.

- US citizen buys a nice little Chinese car.

- If the US consumer pays cash, then his/her bank account is debited and the Chinese car dealer’s account is credited – this has the impact of increasing foreign savings of US dollar-denominated financial assets. Total deposits in the US banking system, so far, are unchanged.

- If the US consumer takes out a loan to buy the car, then his/her bank’s balance sheet now records the loan as an asset and creates a deposit (the loan) on the liability side. When the US consumer then hands the cheque over to the car dealer (representing the Chinese firm – ignore intervening transactions) the Chinese car company has a new asset (bank deposit) and my loan boosts overall bank deposits (loans create deposits). Foreign savings in US dollars rise by the amount of the loan.

- So the trade deficit (1 car in this case) results from the Chinese car firm’s desire to net save US dollar-denominated financial assets and sell goods and services to the US in order to get those assets – it is the only way they can accumulate financial assets in a foreign currency.

What if the Chinese car company then decided to buy US Government debt instead of holding the US dollar-denominated bank deposits?

Some more accounting transactions would occur.

- The Chinese company would put in an order for the bonds which would transfer the bank deposit into the hands of the central bank (Federal Reserve) who is selling the bond (ignore the specifics of which particular account in the Government is relevant) and in return hand over a bit of paper called a bond to the Chinese car maker’s lawyers or representative.

- The US Government’s foreign debt rises by that amount.

- But this merely means that the US Government promises, on maturity of the bond, to credit the Chinese car firm’s bank account (add reserves to the commercial bank the car firm deals with) with the face value of the bond plus interest and debit some account at the central bank (or whatever specific accounting structure deals with bond sales and purchases).

If you understand all of that then you will clearly understand that this merely amounts to substituting a non-interest bearing reserve balance for an interest-bearing Government bond. That transaction can never present any problems of solvency for a sovereign government.

The US consumers get all the real goods and services and the Chinese have bits of paper.

I know some so-called progressives worry about the stock of debt that the Chinese are holding. But the US government holds all the cards. The debt is in US dollars and they never leave the US system.

The Chinese may decide they have accumulated enough and will seek to alter the real terms of trade (that is, reduce its desire to export to the US). In that situation the US will no longer be able to exploit the material advantages and the adjustment might be sharp and painful. But that doesn’t negate that while the situation is as described the material benefits are flowing in favour of the US citizens (overall).

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Twin deficits – another mainstream myth

- Export-led growth strategies will fail

- What you consume or what you produce?

- Modern monetary theory in an open economy

- Debt is not debt!

- The piper will call if surpluses are pursued …

Question 3:

The creation of a sovereign wealth fund from the proceeds of a budget surplus represents increased national savings.

The answer is False.

From the perspective of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) the national government’s ability to make timely payment of its own currency is never numerically constrained by revenues from taxing and/or borrowing. Therefore the creation of a sovereign fund by purchasing assets in financial markets in no way enhances the government’s ability to meet future obligations. In fact, the entire concept of government pre-funding an unfunded liability in its currency of issue has no application whatsoever in the context of a flexible exchange rate and the modern monetary system.

The misconception that “public saving” is required to fund future public expenditure is often rehearsed in the financial media. In rejecting the notion that public surpluses create a cache of money that can be spent later we note that Government spends by crediting an account held by the commercial banks at the central bank. There is no revenue constraint. Government cheques don’t bounce! Additionally, taxation consists of debiting an account held by the commercial banks at the central bank. The funds debited are “accounted for” but don’t actually “go anywhere” and “accumulate”.

Thus is makes no sense to say that a sovereign government is saving in its own currency. Saving is an act that revenue-constrained households do to enhance their future consumption opportunities. The sacrifice of consumption now provides more funds in the future (via compounding). But the government doesn’t have to sacrifice spending now to spend in the future.

The concept of pre-funding future liabilities does apply to fixed exchange rate regimes, as sufficient reserves must be held to facilitate guaranteed conversion features of the currency. It also applies to non-government users of a currency. Their ability to spend is a function of their revenues and reserves of that currency.

So at the heart of the mis-perceptions about sovereign funds is the false analogy mainstream macroeconomics draws between private household budgets and the government budget. Households, the users of the currency, must finance their spending prior to the fact. However, government, as the issuer of the currency, must spend first (credit private bank accounts) before it can subsequently tax (debit private accounts). Government spending is the source of the funds the private sector requires to pay its taxes and to net save and is not inherently revenue constrained.

However, trying to squeeze the economy to generate these mythical “pools of funds” which are then allocated to the sovereign fund as if they exist is very damaging. You can think of this in two stages.

First, the national government spends less than it taxes and this leads to ever decreasing levels of net private savings (unless there is a strong positive net exports response). The private deficits are manifest in the public surpluses and increasingly leverage the private sector. The deteriorating private debt to income ratios which result will eventually see the system succumb to ongoing demand-draining fiscal drag through a slow-down in real activity.

Second, while that process is going on, the national government is actually spending an equivalent amount that it is draining from the private sector (through tax revenues) in the financial and broader asset markets (domestic and abroad) buying up speculative assets including shares and real estate.

Accordingly, creating a sovereign fund amounts to the government competing in the private equity market to fuel speculation in financial assets and distort allocations of capital.

However, as you can see from pulling it apart, this behaviour has been grossly misrepresented as providing “future savings”. Say the sovereign government ran a $15 billion surplus in the last financial year. It could then purchase that amount of financial assets in the domestic and international capital markets. But from an accounting perspective the Government would no longer have run that surplus because the $15 billion would be recorded as spending and the budget would break even.

In these situations, the public debate should be focused on whether this is the best use of public funds. It would be hard to justify this sort of spending when basic infrastructure provision and employment creation has been ignored for many years by neo-liberal governments.

So all we are talking about is a different portfolio of assets.

The following blog may be of further interest to you:

Question 4:

Engaging unemployed workers in a government public works program to dig a large hole and fill it in again on a daily basis will provide no enduring benefit to national income.

The answer is False.

This question allows us to go back into J.M. Keynes’ The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money. Many mainstream economics characterise the Keynesian position on the use of public works as an expansionary employment measure as advocating useless work – digging holes and filling them up again. The critics focus on the seeming futility of that work to denigrate it and rarely examine the flow of funds and impacts on aggregate demand. They know that people will instinctively recoil from the idea if the nonsensical nature of the work is emphasised.

The critics actually fail in their stylisations of what Keynes actually said. They also fail to understand the nature of the policy recommendations that Keynes was advocating.

What Keynes demonstrated was that when private demand fails during a recession and the private sector will not buy any more goods and services, then government spending interventions were necessary. He said that while hiring people to dig holes only to fill them up again would work to stimulate demand, there were much more creative and useful things that the government could do.

Keynes maintained that in a crisis caused by inadequate private willingness or ability to buy goods and services, it was the role of government to generate demand. But, he argued, merely hiring people to dig holes, while better than nothing, is not a reasonable way to do it.

In Chapter 16 of The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, Keynes wrote, in the book’s typically impenetrable style:

If – for whatever reason – the rate of interest cannot fall as fast as the marginal efficiency of capital would fall with a rate of accumulation corresponding to what the community would choose to save at a rate of interest equal to the marginal efficiency of capital in conditions of full employment, then even a diversion of the desire to hold wealth towards assets, which will in fact yield no economic fruits whatever, will increase economic well-being. In so far as millionaires find their satisfaction in building mighty mansions to contain their bodies when alive and pyramids to shelter them after death, or, repenting of their sins, erect cathedrals and endow monasteries or foreign missions, the day when abundance of capital will interfere with abundance of output may be postponed. “To dig holes in the ground,” paid for out of savings, will increase, not only employment, but the real national dividend of useful goods and services. It is not reasonable, however, that a sensible community should be content to remain dependent on such fortuitous and often wasteful mitigations when once we understand the influences upon which effective demand depends.

So while the narrative style is typical Keynes (I actually think the General Theory is a poorly written book) the message is clear. Keynes clearly understands that digging holes will stimulate aggregate demand when private investment has fallen but not increase “the real national dividend of useful goods and services”.

He also notes that once the public realise how employment is determined and the role that government can play in times of crisis they would expect government to use their net spending wisely to create useful outcomes.

Earlier, in Chapter 10 of the General Theory you read the following:

If the Treasury were to fill old bottles with banknotes, bury them at suitable depths in disused coalmines which are then filled up to the surface with town rubbish, and leave it to private enterprise on well-tried principles of laissez-faire to dig the notes up again (the right to do so being obtained, of course, by tendering for leases of the note-bearing territory), there need be no more unemployment and, with the help of the repercussions, the real income of the community, and its capital wealth also, would probably become a good deal greater than it actually is. It would, indeed, be more sensible to build houses and the like; but if there are political and practical difficulties in the way of this, the above would be better than nothing.

Again a similar theme. The government can stimulate demand in a number of ways when private spending collapses. But they should choose ways that will yield more “sensible” products such as housing. He notes too that politics might intervene in doing what is best. When that happens the sub-optimal but effective outcome would be suitable.

So the answer is false. As long as the road builder is paying on-going wages to construct, tear up and construct the road again then this will be beneficial for aggregate demand. The workers employed will spend a proportion of their weekly incomes on other goods and services which, in turn, provides wages to workers providing those outputs. They spend a proportion of this income and the “induced consumption” (induced from the initial spending on the road) multiplies throughout the economy.

This is the idea behind the expenditure multiplier.

The economy may not get much useful output from such a policy but aggregate demand would be stronger and employment higher as a consequence.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

Premium Question 5:

A strategy to force the government to balance its budget means that the private domestic sector has to be continuously accumulating debt overall unless the current account moves into surplus.

The answer is True.

This is a question about the sectoral balances – the government budget balance, the external balance and the private domestic balance – that have to always add to zero because they are derived as an accounting identity from the national accounts. The balances reflect the underlying economic behaviour in each sector which is interdependent – given this is a macroeconomic system we are considering.

To refresh your memory the balances are derived as follows. The basic income-expenditure model in macroeconomics can be viewed in (at least) two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of spending; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the income produced. Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances.

From the sources perspective we write:

GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

From the uses perspective, national income (GDP) can be used for:

GDP = C + S + T

which says that GDP (income) ultimately comes back to households who consume (C), save (S) or pay taxes (T) with it once all the distributions are made.

Equating these two perspectives we get:

C + S + T = GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

So after simplification (but obeying the equation) we get the sectoral balances view of the national accounts.

(I – S) + (G – T) + (X – M) = 0

That is the three balances have to sum to zero. The sectoral balances derived are:

- The private domestic balance (I – S) – positive if in deficit, negative if in surplus.

- The Budget Deficit (G – T) – negative if in surplus, positive if in deficit.

- The Current Account balance (X – M) – positive if in surplus, negative if in deficit.

These balances are usually expressed as a per cent of GDP but that doesn’t alter the accounting rules that they sum to zero, it just means the balance to GDP ratios sum to zero.

A simplification is to add (I – S) + (X – M) and call it the non-government sector. Then you get the basic result that the government balance equals exactly $-for-$ (absolutely or as a per cent of GDP) the non-government balance (the sum of the private domestic and external balances).

This is also a basic rule derived from the national accounts and has to apply at all times.

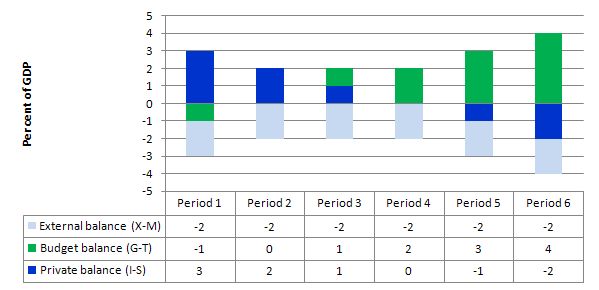

The following graph with accompanying data table lets you see the evolution of the balances expressed in terms of percent of GDP. I have held the external deficit constant at 2 per cent of GDP (which is artificial because as economic activity changes imports also rise and fall).

To aid interpretation remember that (I-S) > 0 means that the private domestic sector is spending more than they are earning; that (G-T) < 0 means that the government is running a surplus because T > G; and (X-M) < 0 means the external position is in deficit because imports are greater than exports.

If we assume these Periods are average positions over the course of each business cycle (that is, Period 1 is a separate business cycle to Period 2 etc).

In Period 1, there is an external deficit (2 per cent of GDP), a budget surplus of 1 per cent of GDP and the private sector is in deficit (I > S) to the tune of 3 per cent of GDP.

In Period 2, as the government budget enters balance (presumably the government increased spending or cut taxes or the automatic stabilisers were working), the private domestic deficit narrows and now equals the external deficit. This is the case that the question is referring to.

This provides another important rule with the deficit terrorists typically overlook – that if a nation records an average external deficit over the course of the business cycle (peak to peak) and you succeed in balancing the public budget then the private domestic sector will be in deficit equal to the external deficit. That means, the private sector is increasingly building debt to fund its “excess expenditure”. That conclusion is inevitable when you balance a budget with an external deficit. It could never be a viable fiscal rule.

In Periods 3 and 4, the budget deficit rises from balance to 1 to 2 per cent of GDP and the private domestic balance moves towards surplus. At the end of Period 4, the private sector is spending as much as they earning.

Periods 5 and 6 show the benefits of budget deficits when there is an external deficit. The private sector now is able to generate surpluses overall (that is, save as a sector) as a result of the public deficit.

So what is the economics that underpin these different situations?

If the nation is running an external deficit it means that the contribution to aggregate demand from the external sector is negative – that is net drain of spending – dragging output down.

The external deficit also means that foreigners are increasing financial claims denominated in the local currency. Given that exports represent a real cost and imports a real benefit, the motivation for a nation running a net exports surplus (the exporting nation in this case) must be to accumulate financial claims (assets) denominated in the currency of the nation running the external deficit.

A fiscal surplus also means the government is spending less than it is “earning” and that puts a drag on aggregate demand and constrains the ability of the economy to grow.

In these circumstances, for income to be stable, the private domestic sector has to spend more than they earn.

You can see this by going back to the aggregate demand relations above. For those who like simple algebra we can manipulate the aggregate demand model to see this more clearly.

Y = GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that the total national income (Y or GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

So if the G is spending less than it is “earning” and the external sector is adding less income (X) than it is absorbing spending (M), then the other spending components must be greater than total income.

Only when the government budget deficit supports aggregate demand at income levels which permit the private sector to save out of that income will the latter achieve its desired outcome. At this point, income and employment growth are maximised and private debt levels will be stable.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

Apropos Question #4: Excellent reasoning! Tomorrow I will write a blog why all Germans and Austrians are Keynesians although they either deny it or don’t know it. Blowing up the Viennese sky with rockets is a perfect substitute for digging holes in mother earth. Happy 2012.

Grudgingly agree with question 1)

Bill wins again

One day…

Stephan,

all the best for the new year.

And I’m looking forward to how the Germans/Austrians are closet Keynsians. It should be rather entertaining.

Cheers

Graham Wrightson

Bill, regarding this: Keynes clearly understands that digging holes will stimulate aggregate demand when private investment has fallen but not increase “the real national dividend of useful goods and services”.

But then again, stimulating aggregate demand increases “the real national dividend of useful goods and services”, hole diggers go shopping. In other words, It is not necessary that receivers of the government payments do something useful for the real national dividends to go up.

Question 5 is all very true. The issue though is whether the optimal state for public purpose would be to have a zero trade deficit and zero net savings. If foreign holdings of the issuing government’s bonds and bank reserves were subjected to an asset tax (collected electronically as “negative interest”) then that would encourage trading partners to buy real goods and services rather than hording financial assets. That would provide jobs and support the skill base in what otherwise would have been the trade deficit nation. It would also prevent despotic elites in exporting nations from appropriating their national earnings. Financial assets can be hoarded by dictators etc far more easily than real goods and services can. We have set up a tragic situation where we exchange dictators’ electronic account statements in our asset markets for real goods from despotic regimes. That keeps our currency strong but actually hurts those of us who would rather have real jobs providing stuff for the people in countries who provide us with stuff not to mention impoverishing the people in those countries.

We need a system where imbalances are self correcting. A free floating currency system where an asset tax balances government spending would be a self correcting system wouldn’t it? You talk about “increasing private sector indebtedness” but with all the tax burden shifted onto gross asset values, there would be a massive transfer from debt financing to equity financing. It would tax advantage a very low debt, high investment, bubble free economy free from trade imbalances.

About question 5, it is important to realise that aggregate demand depends on peoples’ take home pay. Shifting the tax burden to being an asset tax would mean that the tax level would not reduce take home pay and so would not reduce aggregate demand.