I have received several E-mails over the last few weeks that suggest that the economics…

Labour market deregulation will not reduce unemployment

Underlining the current obsession with fiscal austerity is an equally long-standing obsession with so-called structural reform. The argument goes that growth can be engendered by deregulating the labour market to remove inefficiencies that create bottlenecks for growth even when fiscal austerity is slashing aggregate demand and killing growth. The 1994 OECD Jobs Study the provides the framework for this policy approach. The only problem is that it failed even before the crisis emerged. But with policymakers intent on slashing aggregate demand, which they know will kill growth, they have to offer something that they can pretend will generate growth. The structural reform agenda has zero credibility in the same way that fiscal austerity has zero credibility.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics released the latest Job Vacancy data today for the November quarter 2011. The highlights (seasonally adjusted) are:

- Over the year to the November-quarter 2011, job vacancies have fallen by 12.1 thousand or 6.3 per cent.

- Over the last quarter, job vacancies have fallen by 6.1 thousand or 3.3 per cent.

- Vacancies in the private sector fell by 11.7 thousand (original data) or 6.7 per cent, while vacancies in the Public sector fell by 500 a decline of 2.8 per cent over the last 12 months.

- The unemployment-vacancy ratio (a measure of the strength of the labour market) was 3.2 in November 2010 and has risen to 3.5 in the November-quarter 2011, a sign of a deteriorating labour market overall. This is still a long way from the astronomic value of 28.2 in the third-quarter 1991, at the height of that recession.

The Sydney Morning Herald report (January 11, 2012) – Job vacancies slide 3.3% – quoted a bank economist as saying that the following vacancy reflect firms delaying their hiring decision because of “fears about the European sovereign debt crisis and the outlook for the Australian economy”.

The major risk areas for large-scale retrenchments appeared at the retail trade, manufacturing, and the real estate sector. The latter two sectors have been already reducing vacancies over the last 12 months.

Household spending is now very muted and that will impact over the next 12 months on the retail sector and related sectors that depend on growth in household spending.

Now what is all this got to do with structural adjustment and labour market deregulation?

In the past, movements in vacancies and unemployment have been misconstrued by proponents of structural adjustment and labour market deregulation.

I last wrote about this topic in the blog – The OECD is at it again and Extending unemployment benefits … an omen and Nobel prize – hardly noble.

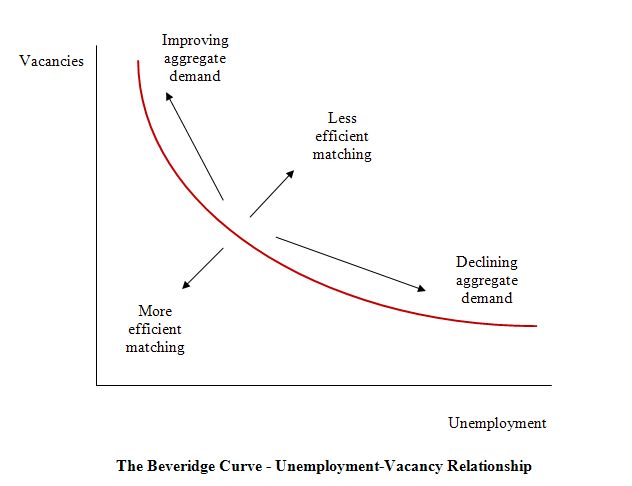

Economists have long used the unemployment-vacancy (UV) relationship, the so-called Beveridge curve, which plots the unemployment rate on the horizontal axis and the vacancy rate on the vertical axis to investigate these sorts of questions. The following diagram is the usual depiction of the UV relationship with vacancies on the vertical axis and unemployment on the horizontal axis. The red line is a UV curve at some point in time.

The logic is that movements along the curve are cyclical events and shifts in the curve are alleged to be structural events. So a movement “down along the red curve” to the south-east suggests a decline in the number of jobs available due to an aggregate demand failure, while a movement “up along the red curve” indicates improved aggregate demand and lower unemployment. If unemployment rises in an economy where there are movements along the UV curve it is referred to as “Keynesian” or “Cyclical” unemployment – that is, arising from a deficiency in aggregate demand.

However, the notion that there is a neat decomposition between shifts in and movements along the curve is highly contested and has not been reliably established in the empirical or theoretical literature.

One of my earliest papers, which came from my PhD work was published in 1987 – ‘The NAIRU, Structural Imbalance and the Macroequilibrium Unemployment Rate’, Australian Economic Papers, 26(48), pages 101-118 – showed that structural imbalances (supply constraints) can be the result of cyclical variations and can be resolved, in part, by attenuating the amplitude of the downturns using fiscal policy.

In other words, there is no decomposition as the mainstream would like us believe.

This is reinforced by work I did a decade ago where it is clearly shown that where the UV curve shifts, almost always the shifts were associated with major recessions which generated structural-like changes in the labour market. In other words, the shifts are driven by cyclical downturns (aggregate demand failures) rather than any changes in autonomous supply side behaviour (like worker attitudes changing, or welfare policy introducing distortions to incentives, etc). More about which later.

The mainstream search literature (for which Nobel Prizes have been awarded) claims that “shifts in the curve” (out or in) indicated non-cyclical (structural) factors were causing the rising falling unemployment. The prize winners claimed this meant that if the UV curve was shifting out then the labour market was becoming less efficient in matching labour supply and labour demand and vice versa for shifts inwards.

The factors that allegedly “cause” increasing inefficiency are the usual neo-liberal targets – the provision of income assistance to the unemployed (dole); other welfare payments, trade unions, minimum wages, changing preferences of the workers (poor attitudes to work, laziness, preference for leisure, etc).

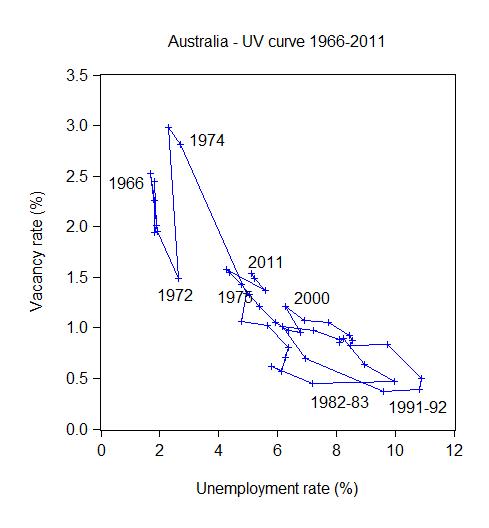

The following graph plots the Beveridge (UV) curve for Australia from 1966 to 2011. The vacancy rate (vacancies as a percent of the labour force) is shown on the vertical axis and the unemployment rate is shown on the horizontal axis.

In the period from 1966 to the mid-1970s, the UV curve was very steep indicating that the economy was at full employment (2 per cent unemployment) and there were always more vacancies unfilled than workers to fill them.

This was a very dynamic period because the firms had to structure their jobs to be attractive in order to entice the scarce supply of workers to take them. The firms also invested heavily in capital equipment to reduce labour inputs and this accelerate productivity (and real wages) growth.

The outward shifts in the UV curve are clearly evident. These outward shifts were common around this time and later (early 1990s) in many nations.

The architects of the OECD Jobs Study – LSE economists Layard, Nickell and Jackman – [Reference: Layard, R., Nickell, S. and Jackman, R. (1991) Unemployment, Macroeconomic Performance and the Labour Market, Oxford University Press: Oxford] were instrumental in misleading the public (and policy makers) about these shifts.

They argued (Pages 4, 38) that these shifts are due to a failure of the unemployed to seek work as effectively as before. They explained the outward shift in the European Beveridge curve by:

… a fall in the search effectiveness … among the unemployed.

They later claimed that (Page 268) that the UV shift were due to “the rise in long-term unemployment, which reduces search effectiveness …”

What does this mean?

LNJ (Page 38) offered the following explanation:

Either the workers have become more choosey in taking jobs, or firms become more choosey in filling vacancies (owing for example to discrimination against the long-term unemployed or to employment protection legislation.

They suggested that the first reason dominates.

There was always what economists call an “observational equivalence problem” in attempting to test for this. This sort of problem arises when movements in the data are consistent with competing theoretical explanations.

In this case, job search time will lengthen when there are large cyclical downturns and the probability of gaining a job decreases.

But with high UV ratios (at the time), it becomes a fallacy of composition to conclude that if all individuals reduced their reservation wage to the minimum (to maximise supply-side search effectiveness) that unemployment would significantly fall (given the small estimated real balance effects in most studies).

Further, unless growth in labour requirements is symmetrical and labour force growth steady on both sides of the business cycle, the pool of unemployed can rise and remain persistently high.

While it is impossible to directly test changes in the motivation of individuals independent of the hypothesis that the shifts are collateral damage of severe recessions the dates when the UV curve shift should give you a good idea of what is going on.

The Australian Beveridge curve shown above exhibited a substantial outward shift during the 1974-75 recession (the first OPEC oil shock). Later instability is apparent in 1982 and then 1991-92.

It is no surprise that these shifts or periods of instability occurred during major demand-side recessions. That is, they are driven by cyclical downturns (macroeconomic events) rather than any autonomous supply side shifts.

At these times, there was no major shift in any policies which the neo-liberals have identified as “structural impediments” to search-effectiveness. The Australian experience is replicated in every nation I have examined closely. The notion that the shifts in the UV curve are due to some policy-induced structural deterioration in search effectiveness beggars belief.

To advance the view that the workers suddenly choose this sharp rise in unemployment and then to design policies which hack into unemployment benefits and other protections to stop reduce the “incentives” for the unemployed to remain that way also beggars belief.

However, undaunted by some empirical evidence, the work of LNJ provided much of the “academic” justification for the OECD Jobs Study agenda, which was released in 1994.

The Jobs Study, exploited the misinformation about the shifts in the UV curve and set out the blueprint for labour market deregulation which has dominated the last 15 or so years. Governments around the world started to implement the OECD agenda – the so-called labour market activism – with more or less vigour.

The OECD constantly pressured governments to abandon the hard-won labour protections which provide job security and fair pay and working conditions for citizens.

Their solution? Cut benefits, toughen activity tests, eliminate trade union influence, abandon minimum wages and reduce any subsidies that prolong the search propensity by workers.

The result? Even before the crisis, unemployment remained well above the full employment levels in most nations; real GDP growth was muted relative to the past; real wages growth has been suppressed relative to productivity growth – leading to a massive redistribution of real income to profits; private gross capital formation has been lower than in the past.

Most economies failed to provide enough employment relative to the preferences of the labour force and persistent demand-deficient unemployment was accompanied by rising underemployment in many countries.

Assessment: the deregulation agenda was a failure.

Even the OECD had to make concessions in this regard.

In the period leading up to the crisis, there was a lot of work aimed at establishing the empirical veracity of the orthodox view that unemployment rose when real wages and workplace protections increased. This has been a particularly European and English obsession. There has been a bevy of research material coming out of the OECD itself, the European Central Bank and various national agencies, in addition to academic studies.

The overwhelming conclusion to be drawn from this literature is that there is no conclusion. These various econometric studies, bias their analyses in favour of finding validity in the orthodox line of reasoning. However, even then, they provide no consensus view as Baker et al (2004) show convincingly.

Just prior to the crisis, partly in response to the reality that active labour market policies have not solved unemployment and have instead created problems of poverty and urban inequality, some notable shifts in perspectives are evident among those who had wholly supported (and motivated) the orthodox approach which was exemplified in the 1994 OECD Jobs Study.

In the face of the mounting criticism and empirical argument, the OECD began to back away from its hard-line Jobs Study position. In the 2004 Employment Outlook, OECD (2004: 81, 165) admitted that “the evidence of the role played by employment protection legislation on aggregate employment and unemployment remains mixed” and that the evidence supporting their Jobs Study view that high real wages cause unemployment “is somewhat fragile.”

Then in 2006, the OECD Employment Outlook entitled Boosting Jobs and Incomes, which claimed to be a comprehensive econometric analysis of employment outcomes across 20 OECD countries between 1983 and 2003 went further. The study sample for the econometric modelling included those who adopted the Jobs Study as a policy template and those who resisted labour market deregulation. The Report revealed a significant shift in the OECD position. OECD (2006) finds that:

- There is no significant correlation between unemployment and employment protection legislation;

- The level of the minimum wage has no significant direct impact on unemployment; and

- Highly centralised wage bargaining significantly reduces unemployment.

The only robust finding that the OECD (2006) demonstrated was that employment protections do not impact on the level of unemployment but merely redistribute it towards the most disadvantaged – including the youth who have not yet developed skills and have little work experience.

That point is obvious. In a job-rationed economy, supply-side characteristics will always serve to only shuffle the unemployment queue. The problem is a shortage of jobs. Unemployment dances very closely to labour demand not labour supply.

Unemployment dancing to labour demand

You will increasingly hear in the coming months policy makers and business lobbyists calling for more structural reform in the labour market. The extreme versions will claim that growth is being constrained by the labour market – thus diverting attention from the fact that firms only employ if they can sell the production that is created.

This diversionary tactic denies that unemployment is a demand phenomena – arising due to a deficiency in demand.

Instead the notion is that unemployment is a result of supply-side constraints that have to be eliminated through deregulation.

The reality is that unemployment is typically a demand phenomenon – that is, it reflects a systemic failure to create enough jobs as a result of deficient aggregate demand.

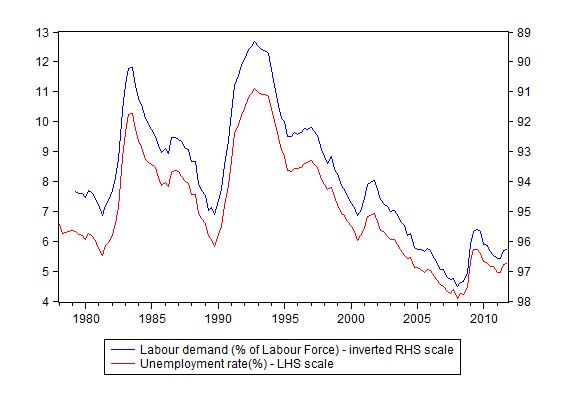

The following graph shows the unemployment rate on the left hand scale plotted against the sum of employment and vacancies (as a percentage of the labour force) as a measure of labour demand on the right hand scale (inverted) from the first-quarter 1978 to the third-quarter 2011 (that is, the data incorporates the latest vacancy information released today).

The correspondence between the two series is striking and a major part of the variation in the unemployment rate is clearly is associated with the evolution of demand.

You can see that labour demand is no falling again – after the effects of the fiscal stimulus through 2010-11 have started to wane upon its withdrawal.

The late Franco Modigliani presented similar graphs for France, Germany, and the United Kingdom, which shows that as job availability declines the unemployment rate rises, with the concomitant outcomes that the search process lengthens as does the average duration of unemployment. Modigliani (2000: 5) concluded:

Everywhere unemployment has risen because of a large shrinkage in the number of positions needed to satisfy existing demand.

Reference: Modigliani, Franco (2000) ‘Europe’s Economic Problems’, Carpe Oeconomiam Papers in Economics, 3rd Monetary and Finance Lecture, Freiburg, April 6.

Where data is available, you could draw similar graphs for most nations.

Phase diagrams

To examine this further, we can examine some phase diagrams.

I first started using phase analysis in this 2001 paper – Exploring labour market shocks in Australia, Japan and the USA, which has since been published but you can get the free working paper version at the link provided. You will find reference in that paper to other relevant material if you are interested.

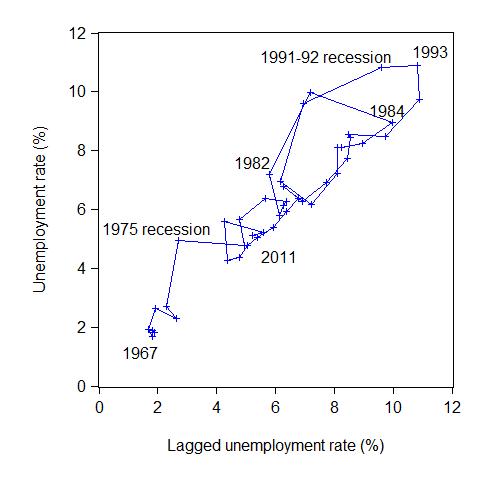

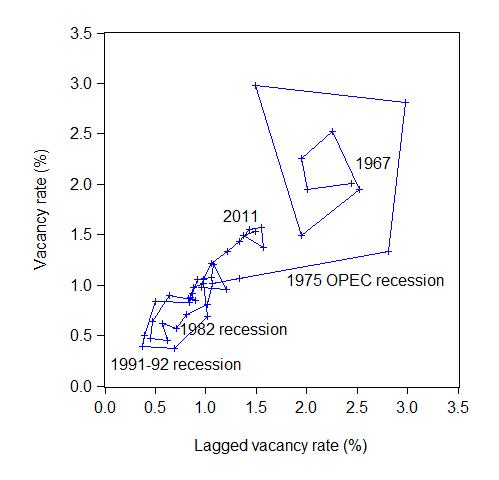

The following two phase diagrams show the current values of the respective time series plotted on the y-axis against the lagged value of the same series on the x-axis. The annual data is from 1966 to 2011 (so the graphs are for 1967 to 2009 given the lagged values).

These scatter plots are helpful in four distinct ways:

First, the charts provide information on whether cycles are present in the data.

Second, the presence of “attractor points” can be determined. The points might loosely be construed as the middle of each of the traced-out ellipses.

Third, the magnitude of the cycles can be inferred by the size of the cyclical ellipses around the attractor points.

Fourth, the persistence (strength) of the attractor point can be determined by examining the extent to which it disciplines the cyclical observations following a shock. Weak attractors will not dominate a shock and the relationship will shift until a new attractor point exerts itself.

The first graph shows the phase diagram for the Australian unemployment rate while the following graph shows the phase diagram for vacancies.

Australia shifted its attractor in the 1974-76 period and the two subsequent recessions have oscillated around this higher point with varying cyclical magnitude. The explanation for Australia’s persistently high unemployment rate revolves around the factors that generated the shift.

It is also clear that the economy takes several years to recover from a large negative shock even if the attractor remains constant. Japan, also shifted its attractor in the period following the first oil shock. The extent of the shift compared to Australia was small. There was also a relatively speedier resolution to the 1980s downturn compared to Australia.

The next graph shows phase diagram for the vacancy rate. Once again, the 1974-75 disturbances in the unemployment rate attractor in Australia also promoted a shift in the vacancy rate attractor, although in this case the movement was downwards.

The supply-side analysis interprets the unemployment shift (and outward movements in the UV curve above) as indicative of a decline in labour market efficiency. The cure – structural adjustment aka labour market deregulation.

But using the same logic, we would interpret the inward shift in the vacancy relationship as a sign of increasing efficiency in the process that matches labour supply and labour demand (less unfilled vacancies are present at any time).

Clearly, both states cannot hold. The unemployment behaviour cannot be indicating a deteriorating structural efficiency while the vacancy relationship is depicting the opposite.

A consistent interpretation for both movements can be found in the view that the Australian economy has been demand constrained as a result of a regime shift in government policy in the mid-1970s. The same findings can be found for other nations with the same explanation.

The rapid rise in unemployment in 1974 was so large that subsequent (lower) growth with on-going labour force and productivity growth could not reverse the stockpile of unemployed.

Whatever endogenous supply effects that may have occurred in skill atrophy and work attitudes were not causal but reactive.

The phase diagram analysis suggests that to restore full employment, the economy needs a major positive shock of a sufficient magnitude to shift the current attractor point downwards.

It is almost definite from the earlier analysis and related empirical work reported in my recent book with Joan Muysken – Full Employment abandoned – that this shock has to be aggregate and focused on the demand side.

That is, large-scale job creation is required.

Interestingly, in a 1997 paper, Richard Layard cast doubt on the supply-side labour market policies that he had initially promoted (in LNJ, 1991 above) and which were so zealously taken up by the OECD and governments around the world.

[Reference: Layard, R. (1997) ‘Preventing Long-Term Unemployment’, in Phillpott, John (ed.), Working for Full Employment, Routledge, London, 190-203]

Layard (1997: 202) concludes that:

If we seriously want a big cut in unemployment, we should focus sharply on those policies which stand a good chance of having a really big effect. It is not true that all polices which are good in general are good for unemployment. There are in fact very few policies where the evidence points to any large unambiguous effect on unemployment and … some widely advocated policies for which there is little clear evidence.

He included changes to “social security taxes”, changes to “job protection rules”, “productivity improvements”, and “decentralizing wage bargaining” as “policies whose effects are difficult to forecast”.

He further argues (Page 192) that further cuts in the duration of benefits would only increase employment at the costs of the creation of an underclass with an “ever-widening inequality of wages.”

His preferred strategy to resolve the unemployment dilemma was government job creation, which would allow people to reacquire:

… work habits … to prove their working capacity … [and to restore] … them to the universe of employable people. This is an investment in Europe’s human capital.

This is, of-course, consistent with our assessment that a Job Guarantee would not only be the most efficient inflation anchor available but would also be sufficient to shift the attractor down to levels consistent with full employment.

Conclusion

This blog was the result of work I am doing on UV relationships at present and coincided with today’s data release from the ABS.

It is relevant because there are already calls for structural reforms, which will clearly further undermine the living standards and job security of workers. This deregulation will reinforce the damage that fiscal austerity is doing in the countries with high unemployment.

The problem for the structural reform lobby is that like the arguments used to justify fiscal austerity, there is no credible evidence available to support claims that labour market deregulation increases employment, real wages, and productivity.

While there have been a number of research articles published in self-serving mainstream journals, supposedly proving that unemployment support reduces employment by undermining the incentives of the jobless to search for work, the reality is that the evidence is deeply flawed and inconsequential.

The literature is replete with such datasets, spurious techniques and other niceties that the mainstream researchers use to cheat on their findings or mislead the reader as to what is actually being demonstrated.

The most sustainable argument that can be maintained is that unemployment is the result of a failure of aggregate demand to generate enough economic activity and employment growth.

That is enough for today!

Bill, I agree that structural factors of the type you cite do not have much to do with currently elevated unemployment levels. On the other hand there is one factor (which could be classified as structural) which could be hindering the recovery. This is that we’ve cut down our reliance on irresponsible lending and borrowing. Assuming this irresponsible behaviour is not resurrected, then a few structural changes in the economy may be required.

As it says in the latest Worthwhile Canadian Initiative post, if Humpty Dumpty is put back together in a way that is different from how he was pieced together before falling, that will take longer than if the bits are just stuck back the way they originally were.

See: http://worthwhile.typepad.com/worthwhile_canadian_initi/2012/01/the-speed-of-recovery-plucking-and-psst.html

OK, I haven’t read the whole post yet, but where does this come from?:

# There is no significant correlation between unemployment and employment protection legislation;

This is what the study says:

However, there is evidence that too-strict legislation will hamper labour

mobility, reduce the dynamic efficiency of the economy and restrain job creation. This

may worsen job prospects of certain groups, like young people, women and the long-term

unemployed.

Ralph: Actually, I think Bill and I might be on the same page here, at least roughly.

Oh my God, Bill!

Couln’t help notice this.

> Economists have long used the unemployment-vacancy (UV) relationship, the so-called Beveridge curve

And they wonder why real scientists don’t take them seriously?

What if the majority of the assumed relationship was imposed by other interdependencies, and is not intrinsic? That highly adaptive state is exactly what biological systems are. These orthodox economists can’t see the adaptive agility for the flexible components. Maybe some ultraviolet goggles would let them more easily see the obvious?

I would love to see a poll of economists, including their response to the following questions.

1) In a extremely multi-variate system, how much predictive power is gained by plotting a presumed relationship between any two?

2) And even if a semi-stable relationship if observed, over some time period, would it not make more sense to look for the “presumed” hidden interdependencies with other variables that can make the supposedly related two-variables gyrate wherever wanted, in synchrony or any other permutation desired? So that they’re no longer hidden, but viewed simply as yet more options?

3) Aren’t multi-variate systems chock full of multi-variate “transistor-like” linkages, where diverse indirect control signals – e.g., public_initiative=public_spending – can gate and drive “primary” signals such as vacancy and/or unemployment, to any permutations desired?

[In fact, once this perspective is opened, it’s clear that, like with other transistors, it’s more productive to treat any optional “hole” to be filled – whether noticed & labeled as a vacancy or not – as the vehicle for fulfilling system potential.]

ps: It’s the epitome of irony that the city of Darwin hosts orthodox economists wielding more influence than their biologists, engineers or other system scientists. The emperor not has only no clothes, he has no logic either. I’m more & more of the opinion that orthodox economics is an orthodoxy invented by the powerful, for the powerful, and is failing totally in democratizing it’s own views. It’s turned into ideological propaganda for a presumed ruling class.

You have to wonder what’s in the beveridge they’re drinking. And who’s preparing the formula fed to students. It’s spawning Irrelevantivity Theory. You can almost visualize the Space Crime Curvature in all the self-fraud.

“Interestingly, in a 1997 paper, Richard Layard cast doubt on the supply-side labour market policies that he had initially promoted (in LNJ, 1991 above) and which were so zealously taken up by the OECD and governments around the world.”

This sounds to me like scientific behavior, i.e. changing their view in light of evidence. I seem to recall that you stated similar about the godfather of the NAIRU concept. Might these be “mainstream economists” who are scientific enough to affect a change?

From the above, it is apparent to me that most economists have no idea how the world works, are not scientists, and practice voodoo.

No wonder Reagan called it “VooDoo Economics”

Ralph in particular spouts non-sense.

To build an economic paradigm for macro economics which does not take into consideration the following metrics for policy is absurd:

In particular, labor’s share of GDP, should be a policy metric. The Golden Era of the OECD saw this at ~60%. I assert that policy should manage this ratio, raising the JG wage when it goes below this value, and lowering the JG wage when it exceeds this value.

Next, the ratio of highest paid to lowest paid in companies was ~ 36:1 during the Golden Era. I assert that policy should manage this ratio, enhancing the power of unions when it exceeds this value, and curbing the power of unions when it is less than this value

Next, national service. All young adults between 18-24 should be in national service, both men and women. Everyone should spend the first two years in shit jobs meeting national needs. During the second year all should be tested via a battery like the SAT. The top 15% as shown on tests like the SAT should be offered full scholarships for tertiary education, in fields necessary for national development. The next 20% should be offered Technical training. The top 50% should be offered enlistment in the 6 uniformed services(navy, marine corps, coast guard, army, airforce, public health service) with the tertiary bound offered Officer training. The bottom 50% should be further stratified into apprentice ship bound and unskilled labor. Upon completion of national service all graduates get the equivalent of the GI bill, that is the opportunity to continue their education under scholarship, at whatever level they choose.

This program would be part of the JG regime, and would qualify participants for social security pension, starter home loans, and other incentives appropriate for those starting families.

Folks like Ralph can’t see the forest for the trees. They are so focused on immediate gratification they don’t acknowledge the importance of human capital in the system. For example:

My uncle went to university and studied engineering after WWII under the GI bill. None of his siblings went to University. He was the first, and his father was a master carpenter, not a university grad. My uncle was responsible for critical systems on the Vanguard Project, the Navy’s first earth orbit satellite program at Martin Marietta.

I went to university and studied Chemistry, Biology, Calculus, Physics, and Economics. I taught at the primary, secondary, and tertiary levels. My students are at Stanford, University of South Wales, Delft, and other top schools. I invented the paging and handoff algorithms necessary for second generation cellular to ring phones anywhere in the network. I co-invented thumbprint scanning. I automated the SATURN auto assembly line. I developed NexTel’s billing system, and many other key systems.

My doctorate was funded via the GI bill. The investment made by my country in me paid handsome dividends.

Dr. George W. Oprisko

Executive Director

Public Research Institute

www. publicresearchinstitute.org

With regard Ralph’s comment. Ponzi finance was necessary for full employment in the OECD

BECAUSE SHORT SIGHTED ECONOMIC POLICY MADE BY THE LIKES OF YOU, STAGNATED WAGES

If the JG was implemented and managed to restore labor’s GDP fraction to 60%, the amount of lending necessary to maintain

full employment would be much less, and the ability of households to repair their balance sheets would be greatly improved, and the speed of this activity heightened.

Dunno about Bill, but Steve Keen has important points here. Lending activity adds to demand when growing, and detracts from demand when shrinking. It is vital that something like the JG exist to dampen these swings.

INDY

George, I think your proposals would go along way to sort out the ‘unemployables’ that Ralph frets over. (that is, the tragic human by products of the current arrangements).

What I find most remarkable about the push for labour market deregulation since the mid-90s (here in Germany it didn’t come to fruition until 2003) was the kind of utter nonsense you were able to spout about the connection between labour market institutions and unemployment. My favourite bit has to be this one from the OECD Jobs Study quoted in Baker et al:

“According to Chapter 8 of the Jobs Study (OECD 1994, p. 178):

‘In some countries, there have been major reforms in benefit entitlements which give some more specific idea of how long lags may be. In Canada, entitlements rose in 1972 and unemployment rose unusually in 1978 and more strongly around 1983. In Finland, entitlements rose in 1972 and unemployment rose sharply (in contrast to its Scandinavian neighbors) through to 1978; in Ireland, changes increasing entitlements occurred over 1971 to 1985, and its rise in unemployment was particularly large (as compared to other European countries) from 1980 to 1985. In Norway, major increases in entitlements occurred in 1975 and 1984 (although also before and after these dates), and unemployment rose exceptionally around 1989. Entitlements rose in Sweden in 1974 and in Switzerland in 1977, with major rises in unemployment in 1991 in both cases. These experiences suggest lags between rises in entitlements and later sharp rises in unemployment of 5-10 years for Canada, Ireland and Finland but perhaps 10 to 20 years in Norway, Sweden and Switzerland.’

Such breathtaking leaps in association must require extremely strong theoretical priors. As Manning (1998, p. 144) puts it, “I think that we would all agree that this is absurd. In fact, one could write a very similar paragraph relating performance in the Eurovision Song Contest to unemployment.”

@ Eclair

I am still puzzled on the reasoning of some mainstream thinking people – that someway if you make firing people easier, there will be more employment!

I still remember a debate going on the TV over the cut of the firing compensations (what workers USED to get when they were fired for reasons outside their control – now it’s almost nothing), one fiscal law specialist was critising the Government approach. He said “When companies move to a country they don’t do it with firing costs in mind, they think how they are going to start producing. If they don’t, they are not serious”. While he was not an economist, he pretty much favoured other “micro” approaches like fixing justice, fighting corruption, improve the education system, etc. He also supported the entry in the euro as a “way to discipline Governments”. He obviously failed in the last part, but that is probably due to his formation in Fiscal Law.

So we are now, in Spain, in the verge of the perfect storm for a decade of 20% or more unemployment. First austerity, and the new goverment is about to approve measures to deregulate the labour market (again). “Employment first” was the slogan during the electoral campaign, now it seems to be “Unemployment first, employment who knows, full employment never”.