The IMF and the World Bank are in Washington this week for their 6 monthly…

The catechism of the IMF

In early January 2012, the IMF published the following working day – Central Bank Credit to the Government: What Can We Learn from International Practices? (thanks Kostas). In terms of the title you can’t learn very much if you start off on the wrong foot. The bottom line is that if the theoretical model that you are using is flawed in the first place then you wont make much sense applying it. The other point is that while this paper presents some very interesting facts about the legal frameworks within which central banks operate and provide a regional breakdown of their results, their policy recommendations do not relate to the evidence at all. This is because they fail to recognise that the patterns in their database (the legal practices) are conditioned by the dominant mainstream economics ideology. So concluding that something is desirable because it exists when its existence is just the reflection of the dominant ideology gets us nowhere. Their conclusions thus just amount to erroneous religious statements that make up the catechism of the IMF and have no substance in reality.

The “paper documents and analyzes worldwide institutional arrangements governing central bank lending to the government in order to identify practices and provide policy recommendations”.

But also imposes the IMF line, but central banks should not lend to “governments” because such behaviour would be inflationary.

Note they use the word “government” in what they call “a broad sense to refer to the state, including entities such as local governments and public enterprises”. Again, this is an ideological conception of the meaning of government. It echoes the notion that central banks are in some way independent of government in the monetary system.

In other words the IMF conception of “government” is not very broad at all and excludes the reality is that both central banks and treasuries engage in “vertical” transactions with the non-government sector which are exclusive to the unit that issues the currency in that monetary system.

In this context, Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) uses the word “government” to refer to the consolidated treasury-central bank operations.

To learn more about vertical transactions as distinct from horizontal transaction in a monetary system please read the following blogs – Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 3

To learn about the consolidation of treasury and central bank operation please read this blog – The consolidated government – treasury and central bank.

The IMF paper says its:

… findings and recommendations are intended to be a useful tool for Fund staff advice and for country authorities interested in revisiting policies for central bank financing of the government.

I would conclude that the findings and recommendations of the paper will further mislead I missed our and provide the basis for misleading and poor advice to countries that the IMF is involved in. The fact is that the main thrust of the paper is erroneous.

The key findings of the paper are summarised as follows:

(i) about two-thirds of the countries in the sample either prohibit central bank lending to the government or restrict it to short-term loans; (ii) most advanced countries and a large number of countries with flexible exchange rate regimes feature strong restrictions on government financing by the central bank; and (iii) when short-term loans are permitted, in most cases market interest rates are charged, the amount is limited to a small proportion of government revenues, and only the national government benefits from this financing.

So the IMF has surveyed current practice which is dominated by a conservative approach to central bank practices largely inherited from the now-defunct convertible currency/fixed exchange rate monetary system.

Based on an empirical survey of existing practice, the IMF uncritically makes the following recommendations.

- As a first best, central banks should not finance government expenditure. The central bank may be allowed to purchase government securities in the secondary market for monetary policy purposes. Restrictions to monetizing the fiscal deficit are even more compelling when countries feature fixed or quasi-fixed exchange regimes to avoid fueling a possible traumatic exit from the peg.

- As a second best, financing to the government may be allowed on a temporary basis. In particular, central bank lending to the government is warranted to smooth out tax revenue fluctuations until either a tax reform permits a stable stream of revenues over time or markets are deep enough to smooth out revenue fluctuations. Financing other areas of the state, such as provincial governments and public enterprises, should not be allowed.

- The terms and conditions of short-term loans should be established by law. Central bank financing should be capped at a small proportion of annual government revenues (on a case-by-case basis), priced at market interest rates, and paid back within the same fiscal year. Communication between the government and the central bank for the disbursement and cancellation of these loans is necessary to facilitate the central bank’s systemic liquidity management.

- As a good transparency practice, transactions that involve central bank financing to the government should be disclosed on a regular basis, including the amount and financial conditions applied to these loans.

The point is that there is no questioning of the existing practice, its historical antecedents, its place in monetary developments, and its theoretical underpinnings. It is just assumed that the existing practice is justifiable and optimal (or first-best in their terminology).

The IMF paper claims that “provisions for central bank lending to the government … may undermine central banks’ autonomy and/or credibility” and that “(f)rom an operational perspective, central bank loans to the government may, if implemented in a disorderly manner, become a source of distortion for monetary operations and for central banks’ liquidity management”.

What do those points mean?

The IMF analysis conveniently ignores “central bank purchases of government securities in the secondary market” which they treat “as part of the central bank’s regular conduct of monetary operations” but recognise “that they may become an indirect form of government financing”.

For example, the current ECB Securities Market Program (SMP) is being justified as a monetary operation to smooth markets and make it easier for them to manage their interest rate target but is, in fact, an unambiguous means of funding Eurozone governments struggling to get private funding at reasonable yields.

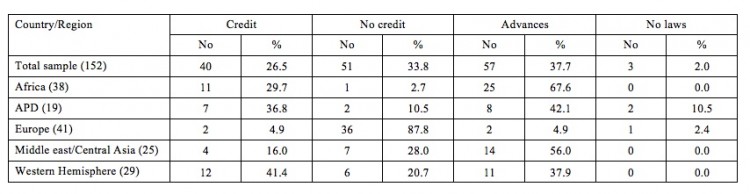

The sample for the study – drawn from the IMFs Central Bank Legislation Database – consists of:

1. 152 countries, including those belonging to 4 currency unions.

2. 38 countries from Africa, 19 from Asia and the Pacific, 41 from Europe, 25 from the Middle East and Central Asia, and 29 from the Western Hemisphere.

The IMF note that:

More than two-thirds of the countries in the sample either prohibit central banks from extending credit to governments or only allow them to grant advances to cope with temporary shortages in government revenues … However, this pattern of restrictions is not uniform across regions. Europe exhibits the most restrictive legal provisions, with these restrictions being driven by the limitations imposed by the treaty establishing the European Community …

I created the following Table to summarise the results of their database analysis. APD is Asia and Pacific. The four categories are: (a) long-term credit provision to government is permitted; (b) credit provision is prohibited; (c) advances of credit are permitted – usually extending an overdraft facility over 12 months; and (d) no legal framework for credit provision.

The Table shows the full sample (152 countries) and then breaks the results up into regions (the numbers in parentheses are country frequency).

The interesting result is that if you take Europe out of the sample, the proportion of nations that allow direct long-term credit provision from the central bank to the treasury rises to 35 per cent (from 27 per cent), the proportion prohibiting long-term credit provision falls to 14 per cent (from 34 per cent), and the proportion which allows short-term credit rises to 50 per cent (from 38 per cent).

So there is a clear regional bias to prohibition of direct central bank credit provision. Where direct long-term credit is allowed the IMF say that “central bank financing exclusively benefit the central government” although some public corporations are also included.

I haven’t time today to investigate this spatial bias in terms of how it might be related to economic performance. The IMF present some correlations which suggest that direct credit provision is “positively correlated” with inflation, “positively correlated” with real GDP growth in all emerging and developing countries but not so in advanced countries (although that result is not “statistically significant”). They admit they did not do any “rigorous empirical analysis” of these relationships.

That is actually an interesting PhD topic that I might propose to the next interested student who seeks my supervision in this area of study.

The IMF paper says that the degree of prohibition seems “to be inversely correlated to the country’s level of development” but that is a different “correlation” to whether prohibition provides for better economic performance. China is relatively undeveloped but outstripping the Eurozone in terms of economic performance at present.

The other result of interest is in the IMF find that “countries featuring flexible exchange-rate regimes have the most restrictive provisions the central bank financing of the government”.

The adoption of inflation targeting regimes has also imposed “strong limitations on central bank financing and fiscal deficits, with the aim of granting central banks political and operational autonomy”.

Please read my blog – Central bank independence – another faux agenda – for more discussion on this point.

So from an MMT perspective, many nations with flexible exchange rates are not taking advantage of their currency sovereignty and are instead operating within rigid monetary frameworks that stifle their capacity to advantage domestic prosperity.

The IMF conclude that:

Conventional wisdom favors the notion that limited central bank lending to the government is conducive to lower inflation and this, if sustained over the long run, promotes higher rates of economic growth.

I love it when mainstream economists use terms like “conventional wisdom favours”. What convention are they actually appealing to here?

It is the convention that is generated by mainstream macroeconomic models which presume – that is, assert – that central bank lending to governments is inflationary and that low rates of real growth also accompany high inflation.

On the latter point, the empirical evidence suggests that inflation has to be very high before real growth is impeded. The scale of inflation that we typically see is well below the thresholds that have been found to damage will growth.

On the first point, the central bank lending is inflationary, the so-called “conventional wisdom” is based upon flawed macroeconomic models and deficient understandings of the way the monetary system works in relation to aggregate spending and monetary operations that might be associated with government spending.

The mainstream framework assumes that one of the reasons why a government should issue debt to “fund” deficit spending and introduce rules that prevent their central banks from directly “funding” such eficit spending is because such practices reduces the inflation risk associated with deficits.

The claim is that the debt-issuance drains the capacity of the private sector to spend and reduces the impact of the public spending on aggregate demand.

The mainstream macroeconomic textbooks all have a chapter on fiscal policy (and it is often written in the context of the so-called IS-LM model but not always).

The chapters always introduces the so-called Government Budget Constraint (GBC) that alleges that governments have to “finance” all spending either through taxation; debt-issuance; or money creation.

This conception – in a fiat monetary system – fails to understand that government spending is performed in the same way irrespective of the accompanying monetary operations. That is, government spending is an act of crediting private bank accounts (or issuing cheques which amounts to the same end).

The GBC literature claims that money creation (borrowing from central bank) is inflationary while the latter (private bond sales) is less so. These conclusions are based on their erroneous claim that “money creation” adds more to aggregate demand than bond sales, because the latter forces up interest rates which crowd out some private spending.

All these claims are without foundation in a fiat monetary system and an understanding of the banking operations that occur when governments spend and issue debt helps to show why.

So what would happen if a sovereign, currency-issuing government (with a flexible exchange rate) ran a budget deficit without issuing debt – that is, was directly funded by the central bank?

Like all government spending, the Treasury would credit the reserve accounts held by the commercial bank at the central bank. The commercial bank in question would be where the target of the spending had an account. So the commercial bank’s assets rise and its liabilities also increase because a deposit would be made.

The transactions are clear: The commercial bank’s assets rise and its liabilities also increase because a new deposit has been made. Further, the target of the fiscal initiative enjoys increased assets (bank deposit) and net worth (a liability/equity entry on their balance sheet).

Taxation does the opposite and so a deficit (spending greater than taxation) means that reserves increase and private net worth increases.

This means that there are likely to be excess reserves in the “cash system” which then raises issues for the central bank about its liquidity management. The aim of the central bank is to “hit” a target interest rate and so it has to ensure that competitive forces in the interbank market do not compromise that target.

When there are excess reserves there is downward pressure on the overnight interest rate (as banks scurry to seek interest-earning opportunities), the central bank then has to sell government bonds to the banks to soak the excess up and maintain liquidity at a level consistent with the target.

In the recent period, more central banks are now offering a return on overnight reserves (so-called deposit facilities) which reduces the need to sell debt as a liquidity management operation.

However, there is no sense that these debt sales have anything to do with “financing” government net spending. The sales are a monetary operation aimed at interest-rate maintenance.

So M1 (deposits in the non-government sector) rise as a result of the deficit without a corresponding increase in liabilities. It is this result that leads to the conclusion that that deficits increase net financial assets in the non-government sector.

What would happen if there were bond sales? All that happens is that the banks reserves are reduced by the bond sales but this does not reduce the deposits created by the net spending. So net worth is not altered. What is changed is the composition of the asset portfolio held in the non-government sector.

The only difference between the Treasury “borrowing from the central bank” and issuing debt to the private sector is that the central bank has to use different operations to pursue its policy interest rate target. If it debt is not issued to match the deficit then it has to either pay interest on excess reserves (which most central banks are doing now anyway) or let the target rate fall to zero (the Japan solution.

There is no difference to the impact of the deficits on net worth in the non-government sector.

Mainstream economists would say that by draining the reserves, the central bank has reduced the ability of banks to lend which then, via the money multiplier, expands the money supply.

However, the reality is that:

- Building bank reserves does not increase the ability of the banks to lend.

- The money multiplier process so loved by the mainstream does not describe the way in which banks make loans.

- Inflation is caused by aggregate demand growing faster than real output capacity. The reserve position of the banks is not functionally related with that process.

So the banks are able to create as much credit as they can find credit-worthy customers to hold irrespective of the operations that accompany government net spending. If a private sector entity wishes to spend and doesn’t have the funds available immediately then, if credit-worthy, they can just go to the bank and borrow.

Further, this doesn’t lead to the conclusion that deficits do not carry an inflation risk. All components of aggregate demand carry an inflation risk if they become excessive, which can only be defined in terms of the relation between spending and productive capacity. The inflation risk occurs when spending chases goods and services.

As a result, it is totally fallacious to think that private placement of debt reduces the inflation risk. It does not.

You may wish to read the following blogs – Why history matters – Building bank reserves will not expand credit – Building bank reserves is not inflationary and The complacent students sit and listen to some of that – for more detailed discussion of this issue.

So it turns out that the “conventional wisdom” is inapplicable to fiat currency systems.

But that doesn’t stop the IMF from laying out what they call their “general principles for the design of an appropriate framework to govern central bank lending to the government”.

So out of nowhere, other than a mainstream macroeconomics text book, and certainly not the result of the research they present in this paper, the IMF conclude the following:

… this paper underscores that central banks should refrain from lending to the government …

The paper doesn’t underscore anything of the sort.

All the paper does is document existing practice, which of course reflects the dominant economic paradigm of the day.

While the paper talks of first best behaviour, there is no analytical framework provided to justify the conclusion that “central banks should refrain from lending to the government”.

The IMF also claim that:

Governments in industrial countries and emerging market economies should have no access to central bank money because they can raise money to finance fiscal deficits from domestic and international capital markets.

This is equivalent, in a fiat monetary system, to saying that the government should create an elaborate deception that it is being funded by the private sector when in fact it is just borrowing what it has already spent.

In the process, the elaborate institutional structure that the government creates to issue date to maintain this illusion that it is revenue constrained, is tantamount to creating a complicated and resource intensive system of corporate welfare.

Moreover, as I noted before, is conclusion is just an article of IMF faith rather than being an evidence-based result of their research. It is the equivalence of a religious statement.

I laughed when I read the next conclusion which applied to nations that operate within fixed exchange rate mechanisms, such as the Eurozone.

The IMF say that in these cases “countries should consider adopting a more restrictive legislation to limit central banks from monetizing fiscal deficits”.

So not only is the IMF advocating the perpetuation of these restrictive exchange-rate relationships, which reduce the flexibility of governments to advance domestic prosperity, but they are also advocating that such governments should be at the behest of the private bond markets.

The current malaise in the Eurozone should disabuse us of advocating either constraint on the choices available to the democratically elected government of the nation.

The IMF also notes that the capacity of central banks to “purchase government securities in the secondary market exclusively for monetary policy purposes” should be restricted and limited to “extreme circumstances”.

They think that these sort of transactions should be limited “exclusively for the purposes of monetary operations”, by which they presumably mean liquidity management.

From an MMT perspective, there should be no restrictions on the central bank to manage interest rates (yields) along the yield curve.

Clearly the motivation expressed by central bankers in the US and the UK in relation to the quantitative easing in the last several years – that is, to expand the capacity of banks to lend – was erroneous, but they were actually engaged in managing long-term interest rates.

Quantitative easing could only have stimulated the economy via the latter impact on interest rates. The fact that it appears to have a relatively small impact is because the private sector has reduced its borrowing propensity as it engages in necessary deleveraging.

There were several other suggestions, all of which related to limiting the capacity of the democratically elected government to use its fiscal tools for benefit.

All were relatively pernicious, but this particular one caught my eye:

The law should protect the central bank against the event that the government does not pay its obligation on time. The central bank should be empowered to debit the government account it holds, or to issue marketable securities on behalf of the government for a value equal to the loan plus interest in arrears.

So when unelected and unaccountable part of the government bureaucracy would be empowered to undermine the statistical capacity of the democratically elected government.

But once again this is just a statement of IMF faith and doesn’t follow at all from the research being presented.

Conclusion

This is one of those papers that could have been restricted to just documenting the patterns in the database.

At that level, the results were of interest and provided some good information on the regional patterns of central bank restrictions.

But the inference that they conducted, had nothing to do with the evidence presented.

First, they failed to recognise that the empirical patterns in the database are conditioned by the dominant economic ideology. Of-course we will find a majority of nations with legal frameworks preventing the central bank from providing long-term credit to governments.

That tells you nothing about the desirability of such a practice given that the dominant ideology considers central bank advances to governments to be toxic.

It’s just a circular exercise.

They could have renamed the paper – the Catechism of the IMF.

Saturday quiz

The Saturday quiz will be back sometime tomorrow – and I promise that I am trying to ensure everybody gets 5 out of 5 correct so that I can stop preparing them.

That is enough for today!

The IMF,the World Bank,the rating agencies etc etc ad nauseum – why do these dangerous fools have any credibility given their disastrous histories?

The psychology of this mass insanity is quite fascinating.I suppose we will have to wait till the full catastrophe appears in the rear view mirror in order to get a handle on it.

It’s how you do politics. You get some institution or allegedly independent third party to concoct a paper wrapping the religious beliefs in some sort of pseudo-scientific format.

Then when you’re pushing those beliefs you refer to the authority of the independent report.

It’s a classic trick that is based on the ‘appeal to authority’ logical fallacy.

The sad thing is that it works, because reason is so undermined in the population.

It’s interesting to note that QE in the UK recently has involved secondary market intervention by BoE in the maturity region where there is new gilt issuance. A charade, in other words.

What is interesting is that if one reads the Appendix III of the paper (which documents specific per country institutional arrangements) he will find out that (with the exception of Eurozone) most developed countries *do* allow central bank direct credit to the government. Canada, Japan and the US fall in that category while the UK is not included in the appendix.

So even the IMF findings about developed countries arrangements are highly biased due to the Eurozone policy restrictions.

“The sad thing is that it works, because reason is so undermined in the population.”

That was never more true than on Newsnight – reputedly BBCs flagship TV news journalism program – last night.

In a round table discussion on the failure of capitalism-as-we-know-it and the lack of alternatives, between a Tory spin doctor, a banker and a right-wing Labour MP (some balance …), the Tory was allowed to posit that, as long as we accept individual property rights and their exchange, then we have to accept “capitalism”, ergo as-we-know-it, ergo the neo-liberal variation. This went unchallenged.

A similar argument on a satirical news program a few weeks ago was shot down in flames by comedians and the editor of Private Eye. Such is the state of mainstream journalism in the UK right now.

that was indeed a gruelling, depressing episode of newsnight, though eric hobsbawm’s earlier point, that capital no longer seem to need workers was spot on.

Kostas Kalevras says:

Friday, January 20, 2012 at 21:50

” . . . (with the exception of Eurozone) . . . ”

Paragraph 2 of Article 123 of the Lisbon treaty specifically permits Central Bank lending to “publicly-owned financial institutions”?

Would it help California (or any state within the USA) to setup a state bank to use the money created by the bank to use during times of austerity (like right now) with the understanding that when the bank loan is paid off it disappears? If it is a home mortgage the return happens in more than twenty years.

@partha

Only if the Fed authorized the state bank to borrow reserves and then use them to buy California bonds, which to my knowledge isn’t in the cards. Beyond that the bank would have no ability to create money and fund California’s spending. That privilege is limited solely to the consolidated federal government.

«It’s how you do politics. You get some institution or allegedly independent third party to concoct a paper wrapping the religious beliefs in some sort of pseudo-scientific format.»

And it works for everything! Our previous prime-minister was discovered to have hired an OECD ex-employee to write a nice “paper” complimenting the state of education in Portugal. Needless to say it was presented as a OECD paper and that the state of Education is everything but fine.

“The sad thing is that it works, because reason is so undermined in the population”.

Seems to me it’s not a question of the ignorance (of relatively abstruse economic theory – loftily equated here with “reason”) on the part of a populace that’s the problem. It was ever thus and always will be, but that never impeded ordinary people going about their daily lives using a blend of impulse, instinct and horse-sense.

The problem is the eternal one:- the pursuit by a minority of a disproportionate share of political power. That both gives them privileged access to wealth and is the principal means of maximising wealth, recursively, once acquired.

Truisms I’m afraid but a perhaps necessary corrective to the belief that seems to prevail here that these basic drives *must* (surely) be able to be tempered or re-directed by reasoned persuasion. They’re not: they’re amenable only to countervailing (countervailingly crude, that is) discouragement, by sufficiently powerful opposed interests.

The IMF was and is designed as the creature of the neo-liberal ideology which captured the seats of power in the West three decades ago, following a well worked-out plan which (beginning in Pinochet’s Chile) succeeded brilliantly in its strategic aims (Michael Hudson among others has done a superb job documenting that recent history). So, of course it booms out a message consonant – as Bill says – only with that ideology and therefore fundamentally flawed. But propagandists don’t stop just because dissidents comprehensively rubbish their assertions, only when their political masters are dethroned.

The Irrational Monetary Fund bureaucrats make no mention of the private financial sector bursting inflationary bubbles that cause so much mayhem. What a bunch of constipated dogmatists!

Hello bill

Made a search for central bank financing and you came up! Read quickly. Will go back and review later. Interesting indeed.