The IMF and the World Bank are in Washington this week for their 6 monthly…

IMF – the height of hypocrisy but still wrong as usual

When I read the latest news from the IMF early this morning I sent out a tweet saying that it was the height of hypocrisy for the IMF now to be trying to reclaim the high ground in the current economic debate by lecturing nations about the dangers of fiscal austerity. The IMF will always be part of the problem rather than the solution. They are consistently the architects of misinformation and bully national governments on the basis of that misinformation only to come back 3 months later and say “gee whiz”, look how bad things become. Currently the IMF is pleading for more funds. If I was a national government contributing to this bullying, incompetent organisation I would immediately cancel the cheque and, instead, spend the money pursuing domestic growth for the benefit of the citizens is that rely on my decisions. The current position of the IMF represents the height of hypocrisy. Further their forecasts are significantly error prone as usual. Wrong models will generally produce terrible forecasts that have to be continually revised. In the case of the IMF, these errors are also systematically biased by the ideological nature of their approach to macroeconomics.

On January 24, 2012, the IMF released their World Economic Outlook Update – which has raised alarm bells in the World’s press. The IMF also released their Fiscal Monitor Update on January 24, 2012. Both documents are carried the same confused message.

Somehow the current solution requires fiscal consolidation within a growth strategy. The IMF has worked out that the medium-term resolution this crisis is for economies to resume growth. They also know full well that growth in aggregate spending is required to achieve that. The problem is that they are fundamentally compromised by the irreconcilable conflict between their obsession fiscal austerity and the reality that spending generates growth.

I last considered the inaccuracy of the IMF forecasts in this blog – 100 per cent forecast errors are acceptable to the IMF and earlier in this blog – The first act of fiscal consolidation – terminate the IMF funding.

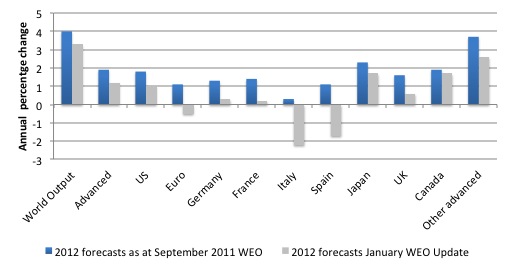

The latest WEO upgrade provides new forecasts for 2012, considerably less optimistic than those that were available in the full September 2011 release of the WEO.

The following graph compares the 2012 forecasts as at September 2011 with the latest IMF forecasts that came out yesterday. The blue bars of the earlier forecasts for 2012 and the grey bars are the most recent. In every case, the forecasts are now significantly more pessimistic.

In the case of the Eurozone the IMF has gone from a 1.1 per cent annual growth projection to a -0.5 real growth projection for 2012 in the space of 3 months.

In the case of Italy, it is flipped from a positive growth scenario 0.3 per cent per annum to a 0.6 contraction.

In the case of Spain, the revisions are even more stark. Workers in September 2011 they were predicting a 1.1 per cent real growth rate to 2012 and has now been revised to -0.3 growth rate.

The fact is that the optimistic 2012 forecasts presented in September 2011 whenever realistic. It was quite clear that the fiscal austerity being imposed upon the Eurozone was always going to result in sharp contractions in real growth.

The IMF has a history of providing overly optimistic growth forecasts at a time when it is bullying national governments to impose fiscal austerity. The opposite is also the case, their growth estimates that typically conservative when governments are introducing fiscal stimulus packages, which I put down to the use of models that deny the strength of fiscal policy (and the related multipliers).

That is the inherent bias of their macroeconomic modelling is to downplay the role of government deficits and give excessive weight to Ricardian type effects with respect to private sector spending.

The graph is consistent with this bias. Their constant advocacy of fiscal consolidation is based on their view that private sector spending was tied to public spending but mostly in an inverse manner (Ricardian equivalence and crowding out). I consider this is more detail below.

Applying that erroneous causality then would lead them to be excessively optimistic at a time of fiscal contraction.

My criticism of the IMF forecasting performance should not be interpreted as being anti-forecasting. Rather it is the systematic bias in their forecasts that render them useless but dangerous.

I consider that a forecasting organisation should be excluded from having policy influence when there is systematic bias in the errors they make which arise from using erroneous models that reflect their free-market ideological leanings rather than capturing the way the economy actually works.

That failure of that ideology has been demonstrated by the crisis and the economics dynamics since the crisis began.

While the errors are bad enough, the danger arises from the fact that the IMF uses these forecasts as a tool to influence economic policy of democratically elected governments. The IMF is never accountable for the policy failures that they inflict on national economies.

According to the WEO Update:

The global recovery is threatened by intensifying strains in the euro area and fragilities elsewhere. Financial conditions have deteriorated, growth prospects have dimmed, and downside risks have escalated … the euro area economy is now expected to go into a mild recession in 2012 as a result of the rise in sovereign yields, the effects of bank deleveraging on the real economy, and the impact of additional fiscal consolidation.

So real growth depends on spending and when the private sector is not spending then the public sector has to fill the gap. As a result of listening to the advice of the IMF among others, the Eurozone nations are cutting by sources of growth.

The IMF say that the “most immediate policy challenge is to restore confidence and put an end to the crisis in the euro area by supporting growth, while sustaining adjustment, containing deleveraging, and providing more liquidity and monetary accommodation”.

Which is otherwise known as the impossible conservative dream.

All of these problems could be simply achieved by increasing budget deficits with the support of the ECB. If the latter announced that it would unconditionally fund growth-based strategies by member governments in the so-called sovereign debt crisis ends immediately.

The IMF also introduce a new narrative in an attempt to rationalise the ongoing anti-deficit mantra with the obvious realisation that fiscal austerity is killing growth. They say:

Countries should let automatic stabilizers operate freely for as long as they can readily finance higher deficits.

What exactly does that mean? The automatic stabilisers operate automatically as a matter of course.

Is the IMF suggesting that the discretionary austerity that is being imposed on national economies in Europe should not also try to compensate for the counter cyclical deficit movements arising from the automatic stabilisers?

Given that a substantial component of the budget deficit outcomes in Europe over the last few years have been of a cyclical nature, that is, driven by the automatic stabilisers, upon what basis does the IMF boss claim a sharp and quick fiscal contraction is required.

In several cases, the Stability and Growth Pact conditions governing the scale of budget deficit outcomes in Europe were violated as a consequence of the operation of the automatic stabilisers.

This new rhetoric appears to be the way the IMF is trying to moderate its hostility to budget deficits yet at the same time be holding itself out to be pro-growth, when it is obvious that the only way out of this crisis is for the economies to grow.

At any rate, national governments which issue their own currency had no funding problems. And the ECB, as noted above, could easily resolve the funding problems of member states in the EMU any time it chose.

The IMF also said that:

Overdoing fiscal adjustment in the short term to counter cyclical revenue losses will further undercut activity, diminish popular support for adjustment, and undermine market confidence.

Which is stating the obvious. But what they can’t bring themselves to say is it any procyclical fiscal adjustment when private spending is weak and unemployment is hard is totally without theoretical justification.

The IMF is playing this cute game now – trying to juggle temporal distinctions – the fiscal austerity is necessary but not in short-term.

When does the short-term become the medium-term? The whole emphasis on fiscal consolidation leads one into a unfathomable dilemma such as the IMF is currently in.

By having these rigid notions that a budget deficit outcome in somehow something that policymakers should target, analysts and commentators will always find themselves compromised like this.

It’s far better to acknowledge that the budget deficit should not be a policy target but rather will reflect the state of the economy. The policy target should be to generate appropriate rates of employment and GDP growth, and let the budget balance be whatever is necessary to achieve that target.

There is no compromise in that position. One would advocate reducing budget deficits when aggregate spending was pushing up against the real capacity of the economy to respond in real terms (that is, by producing the goods and services).

That is, fiscal policy would become typically counter-cyclical. Advocating degrees of pro-cyclical fiscal policy will never produce adequate outcomes on a sustainable basis.

The WEO Update was preceded by a speech in Berlin on January 23, 2012 – Global Challenges in 2012 – given by Christine Lagarde, the IMF boss.

This is the speech wish declined that unless governments adopted a “collective determination to reach a corporate solution”:

… we could easily slide into a “1930s moment”. A moment where trust and cooperation break down and countries turn inward. A moment, ultimately, leading to a downward spiral that could engulf the entire world.

The “1930s moment” was cute rhetoric but totally at odds with the position that the IMF has been adopting.

The IMF boss claimed she was hopeful that “we can avoid such a scenario” for one “simple reason”

… we know what must be done.

Given the IMF’s track record that was an extraordinary statement to make.

She had the audacity to say that the Eurozone has come a long way “in addressing the new realities it faces”.

She was referring to the ESFS, which is incapable of dealing with the scale of the problem it was intended to solve. She was also praising the ECB for making “long-term liquidity available to banks”.

I wonder how the German hosts took the last comment about the ECB.

She outlined 3 imperatives for the Eurozone: ” stronger growth, larger firewalls, and deep integration.”

She claimed that “timely monetary easing will be important” and it brought fiscal austerity “will only add to recessionary pressures”.

But then you get the rub – she claimed that “several countries have no choice but to tighten public finances, sharply and quickly”. So much for the collective and cooperative solution!

And then we encountered the curious concession that appears to have crept into IMF rhetoric. She said:

Automatic stabilizers, which let tax revenues fall and spending rise as the economy weakens, should certainly be allowed to operate.

See the discussion above for why this narrative is nonsensical.

But on the US, the IMF boss claimed the key priorities must be:

… to relieve the burden of household debt and to deal decisively with the issue of public debt … [and that ] … American policymakers need to find a way … of bringing down tomorrow’s deficits-including by reforming entitlements and raising revenue-without bringing down today’s economy.

Again, these cute narrative – keeping the IMF anti-deficit mantra going but trying to hold itself out as being pro-growth.

The only policy priority and macroeconomic level for the US at the moment is to generate enough employment growth to quickly and sharply reducing unemployment rate. That requires an expansion of the budget deficit in the US and a commitment to the private sector that the fiscal support for growth will be maintained for long enough so that they can successfully reduce private debt.

The IMF position is exemplified in the following conclusion drawn by the IMF boss:

… credible measures that deliver and anchor savings in the medium term will help create space for accommodating growth today-by allowing a slower pace of consolidation.

From the Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), governments that issue their own currency do not save in that currency. Running budget surpluses does not provide any extra spending capacity for the national government.

When a user of the currency, such as a household or a firm, spends less than they earn the accumulation of the stock of financial assets (saving) provides increased spending capacity in the future at any given level of income.

A currency issuing government can always spend irrespective of its past fiscal outcomes.

I agree that there has to be credible measures to “deliver and anchor savings” but those savings have to be in the non-government sector which is currently carrying excessive debt levels as a result of the credit binge prior to the crisis.

The only reasonable concept of “fiscal space” relates to the relationship between aggregate spending in the economy and the capacity of the real productive sector to respond to that spending via production of real goods and services.

Once the economy reaches full employment (the inflation barrier) then expanding the budget deficit any further will be inflationary. The government has two choices at that point: (a) maintain the level of stimulus intact; or (b) increase taxes on the non-government sector to reduce its spending capacity and provide more “real” space for public spending.

That choice is not a financial nature but, rather, would reflect the political environment that the government faces.

It is to an absurd proposition to suggest that running surpluses (or sharply reducing deficits) at a time when economic growth is plunging provides the government with “space for accommodating growth today”.

The IMF boss finished her speech with a “funds drive” claiming that the IMF must “step up” its “lending capacity”.

It’s a curious situation really. On the one hand, the IMF is demanding national governments cut spending. Yet on the other hand, the IMF wants the governments to provide them with more funds so they can l lend to other governments, who are wrecking their economies by following the IMF advice (coercion) to reduce spending.

Such is the compromised position of the ideologue. No government should provide the IMF with any additional funds. The world would be better off without the IMF.

Since becoming the IMF boss, the former French finance minister has modified the rhetoric somewhat. For example, on October 10, 2010, the US ABC This Week program ran an interview with the then French Finance minister Christine Lagarde, who is now the IMF head.

When asked to justify the European fiscal austerity obsession, but then finance minister said:

If we do not reduce the public deficit, it’s not going to be conducive to growth. Why is that? Because people worry about public deficit. If they worry about it, they begin to save. If they save too much, they don’t consume. If they don’t consume, unemployment goes up and production goes down. So we need to attack that circle from the deficits.

This is the discredited Ricardian Equivalence argument used by mainstream macroeconomists to justify cutting fiscal deficits.

Ricardian Equivalence refers to the notion (loosely) that households and firms are deliberately refraining from spending as much as they might at present because they expect that the deficits will have to be paid back via higher future tax rates and so are saving to make sure they can pay those future taxes.

The overwhelming evidence negates the validity of the concept. Private spending is flat because people are scared of unemployment, they are trying to pay down debt after the credit-binge, and firms are experiencing poor sales and so have no incentive to create new productive capacity because they can meet their expected sales with existing capacity.

Harvard economist resurrected the modern form of this view in the 1970s. He has been making predictions ever since that are always negated by the subsequent events.

Barro claimed that spends on our behalf and raises money (taxes) to pay for the spending. According the mainstream view, when the budget is in deficit (government spending exceeds taxation) it has to “finance” the gap, which Barro claims is really an implicit commitment to raise taxes in the future to repay the debt (principal and interest).

Under these conditions, Barro then proposes that current taxation has equivalent impacts on consumers’ sense of wealth as expected future taxes.

So the government spending has no real effect on output and employment because individuals assess the total stream of income and taxes over their lifetime in making consumption decisions in each period and save now to meet future tax obligations.

.

In these blogs – Deficits should be cut in a recession. Not! and Pushing the fantasy barrow – I explain in more detail the highly restrictive assumptions that have to hold (in theory) for the notion to even have internal theoretical consistency.

Should any of these assumptions not hold (at any point in time), then the model cannot generate Barro’s conclusions and any assertions one might make based on this work are groundless – that is, purely religious statements.

First, capital markets have to be “perfect” (remember those Chicago assumptions) which means that any household can borrow or

It is clear that none of the required assumptions hold in the real world.

At the time, Barro outlined this notion, there was a torrent of empirical work, particularly after the US Congress gave out large tax cuts in August 1981, which was the first real world experiment possible.

The tax cuts were legislated to be given over 1982-84 to stimulate aggregate demand. Barro’s adherents all predicted there would be no change in consumption and saving should have risen to “pay for the future tax burden” which was implied by the rise in public debt at the time.

But, if you examine the US data you will see categorically that the personal saving rate fell between 1982-84 (from 7.5 per cent in 1981 to an average of 5.7 per cent in 1982-84).

Once again this was an example of a mathematical model built on unreal assumptions generating conclusions that were appealing to the dominant anti-deficit ideology but which fundamentally failed to deliver predictions that corresponded even remotely with what actually happened.

The problem is that the mainstream macroeconomists still hang on to this idea of a “fiscal contraction expansion” and it is evidenced by the former finance minister’s statement above.

She was then challenged to explain why continuing the stimulus in France would not be good for growth. She replied:

… if I look at my numbers, which is better than, you know, theories and — and — and speculations, if I look at my numbers, we’ve stimulated the French economy massively in the year 2009, end of 2008, 2009. And my numbers are now going up. I’ve got growth up 1.6 percent from negative 2.6 percent. I’ve got unemployment down from 9.6 percent down to 9.3 percent. And I’ve got deficits down, as well, from 8.2 percent, where we thought it would be down to 7.7 percent. So the numbers are good. Unemployment is going down. Why would I inject more public money into the system when private investment is picking up?

Which just tells us that the fiscal stimulus had worked and should have been maintained to allow the unemployment rate to continue falling while private investment recovered.

The fact that “private investment is picking up” (at that time) also negates the earlier belief that private sector spending fell when budget deficit rose because private agents feared the deficits.

One wouldn’t inject more “public money into the system” if the pickup in private spending was sufficient to restore full employment. It is quite clear in the French case that the fiscal stimulus had positive early effects but was not sufficient to replace the lost private spending.

Conclusion

The whole emphasis on fiscal consolidation which is underpinned by the flawed IMF concept of “fiscal space” is based upon the adoption of rigid notions that a budget deficit outcome should be a policy target.

Given the endogeneity of the budget outcome (as evidenced by the counter-cyclical nature of the automatic stabilisers), targetting a particular budget outcome will typically lead to failure. The budget outcome will always reflect the state of the economy. When the economy is weak the budget deficit will rise and vice-versa.

The policy target should be to generate appropriate rates of employment and GDP growth, and let the budget balance be whatever is necessary to achieve that target.

There is no compromise in that position. One would advocate reducing budget deficits when aggregate spending was pushing up against the real capacity of the economy to respond in real terms (that is, by producing the goods and services).

That is, fiscal policy would become typically counter-cyclical. Advocating degrees of pro-cyclical fiscal policy will never produce adequate outcomes on a sustainable basis.

Digression – Youth Unemployment

I have been prodding the media for months now trying to get some attention in the national debate for the appalling youth labour market. For more detail see my most recent commentary on the Australian Labour Force data – Australian labour force data – things are getting worse.

On Tuesday, I briefed a journalist at the Sydney Morning Herald article (Chris Zappone) who then wrote this article (January 24, 2012) – Young workers hit by rising unemployment.

That prompted many radio interviews including:

ABC Radio National Breakfast – Youth unemployment: 18,500 teen jobs wiped out in December – Information.

5AA Adelaide – Youth unemployment on the rise.

Last week, ABC Brisbane Morning Show also covered the issue – Worst job figures since 1992.

Most of the other stations have not made the audio publicly available.

That is enough for today!

Doesn’t the fact that the IMF forecasts are always inaccurate prove beyond doubt that Ricardian effects cannot occur. After all the whole premise requires prophetic abilities in the population, and if ‘trained economists’ can’t get it right how are the ordinary people supposed to.

hear hear. I saw that this morning. very bad. On models, this is a paper I found to be enlightening?

Debunking the Myths of Computable General Equilibrium Model

Here is some evidence of expansionary fiscal contraction?

http://www.paulormerod.blogspot.com/2011/11/expansionary-fiscal-contraction.html#comment-form

Hasn’t put Mervyn King off prophecying:

“There is no reason to despair.All crises come to an end, and businesses will find ways to trade with each other and meet the needs of consumers.”

I see no reason why this crisis will not go on forever, but if it does end, it won’t be bacause of Mervyn.

He also announced that:

“Helped by the right policy actions, the UK and world economies can and will recover. And when they do so, they will be on a more sustainable footing than at any point in the past 15 years.”

Sounds nice, but a bit vague.

Interesting (sic) that NS&I Government saving/borrowing has been so popular witht the wealthey that;

“As of March 2011, the Direct Saver had only 19,874 customers but they had saved an average of £85,000 each, amounting to £1.7bn in the accounts.”

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-16703084

Ann Pettifor (UK) has made similar criticisms over the years. No matter how many critics it has and no matter how much evidence is gathered to show how wrong they have always been, they occupy the same social space they have for years.

King doesn’t seem to know what to do. To say that all crises come to an end is to say virtually nothing. Of course, if you have cancer, the pain will eventually ebb, when you are dead. Not vey helpful to you in the meantime. The same goes for King’s vacuous commentary. Brown should have sacked him when PM, but was was constitutionally incapable of making a decision that mattered.

Your blog is wonderfully educational for someone like me, who has no real “economics” qualifications to speak of. However, there’s one thing that bothers me about your posts, specially this one, and it is the constant stream of typos and grammar mistakes that seem to slip under your radar. I think it would be good if you proof read your posts more thoroughly before submitting, even if that meant you would post them later. It makes for an easier reading experience, specially for those who are new to the MMT blogosphere.

Juan,that is a fair criticism,up to a point. But I get the impression that Bill is a very busy man with many irons in the fire and he writes his blog in a hurry and quite often not in his office.

Obviously it would be nice if he had a secretary who could proof read the blogs before posting them but I doubt if the budget runs to that.

Personally,I am just grateful that we have a person of the calibre of Bill Mitchell here in Australia who is standing up for sensible economic policy and is prepared to spend the time and effort to educate students, economic specialists AND the general population.

With some sympathy for Juan, I agree, Podargus: how Bill churns this stuff out on an almost daily basis is beyond me.

I suspect that Bill sometimes dictates into speech recognition software, possibly at brekky with a mouthful of muesli.

Dear Juan (at 2012/01/26 at 6:15) and Podargus and John

Thanks for the criticism. I am aware of the issue. But I set aside a certain amount of time for the blog each day and that is it. Otherwise it would take over everything. There will be more errors in recent days because John is correct in his guess – I have been experimenting with voice recognition software which is definitely not perfect. It is getting better but needs some more training.

In general, the production of my blog involves interaction with databases, spreadsheets, text editors, graphics programs, statistics and econometric programs and external WWW sites etc on a daily basis with lots of swapping between each – writing, capturing and/or producing graphics, reading things etc. I have streamlined it as best I can but I will not go beyond the time I set.

Further, I often do it while sitting waiting for flights or in trains and/or other conveyances and so the world is rarely calm.

But I will try to improve.

best wishes

bill

paul,

these vacuous remarks could have been uttered by Sir Desmond Glazebrook ( http://www.quotefully.com/tvshow/Yes,+Prime+Minister/Sir+Desmond+Glazebrook ). Perhaps King was promoted to his level of incompetence?

Grammar Police are starting to get everywhere.

It’s a worrying sign. You get the impression they are not actually interested in the content, just the typos.

Strange people.

Bill doesn’t need a proof-reader – that’s what we are.

Mention politely what the error in the text is and Bill will usually correct it on his next pass.

That’s the advantage of a dynamic medium over print.

Fear the old for they have wealth, power and they vote. Fear the young for they revolt.