It's been a week of grand fiscal statements. Tuesday, it was for Australia as I…

The US is not an example of a fiscal contraction expansion

Recent data releases suggest that the current economic experience on the two sides of the Atlantic is very different. The latest data shows that the UK economy is now contracting and unemployment is rising as fiscal austerity begins to bite. Conversely, the latest US data shows that growth is on-going and the unemployment rate is finally starting to fall. This may be a temporary return to growth because the political developments that may occur later in this year could see some serious, British-style fiscal austerity being imposed on the US economy. At present though, my assessment of these disparate trends is that fiscal austerity is contractionary if non-government spending is insufficient to offset the decline in public spending. However, some observers are trying to hold out the US experience as vindicating those who believe in the notion of a “fiscal contraction expansion”. But the data tells us clearly that the US is not an example of this mania.

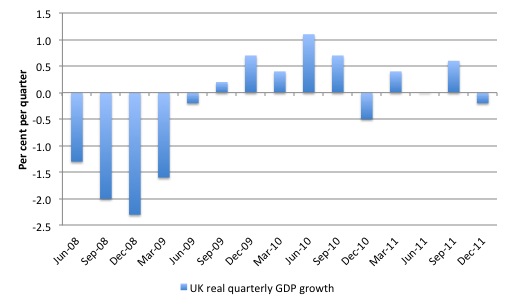

The UK Office of National Statistics released its – latest GDP estimates – for the December quarter 2011 (January 25, 2012) which showed that the British economy contracted in real terms by 0.2 per cent with the production industries contracting sharply by 1.2 per cent.

The following graph shows quarterly real GDP growth in the UK since the second-quarter 2008.

The British government is trying to divert the blame to the Eurozone crisis, which has undoubtedly impacted negatively on British exports. Of-course, if the government really believed that the external environment has deteriorated, then the appropriate reaction would be to bolster domestic demand.

The latest data shows that private domestic spending remains very weak in the face of increasing fiscal austerity which has only just begun. Private domestic spending has been waning for some time now and pre-dates the latest Eurozone developments. The principle reason is the persistently high unemployment combined with the excessive private sector indebtedness left over after the real estate boom.

In that environment, business firms had no incentive to invest because they can meet all existing demand with the capacity already in place.

It is impossible for an economy to grow when private spending his flat, the external sector is in decline, and the government is pursuing a deliberate policy of fiscal austerity.

On the other side of the Atlantic, on January 26, 2012, the US Census Bureau released its latest Manufacturers’ Shipments, Inventories, & Orders data, which “provides broad-based, monthly statistical data on economic conditions in the domestic manufacturing sector. The survey measures current industrial activity and provides an indication of future business trends”,

The data shows that “New orders for manufactured durable goods in December increased $6.2 billion or 3.0 percent … This increase, up five of the last six months, followed a 4.3 percent November increase”.

The data is being interpreted as indicating increased business optimism. The Sydney Morning Herald article (January 27, 2012) – US economy gains as businesses spend more reports that:

Factories are busier in large part because businesses are ordering more communication equipment, industrial machinery and autos. Economists pay close attention to demand for such core capital goods, which are considered a good proxy for business investment plans.

In December, orders for core capital goods rose to a record $US68.9 billion. That’s more than 45 per cent higher than the recession low hit in April 2009.The increase offered some reassurance about the status of the recovery, especially after core capital goods fell in October and November.

Firms only start investing in new capital when they feel that growth prospects are durable.

The US Conference Board also published its Leading Economic Index for December 2011 which:

… increased 0.4 percent in December to 94.3 (2004 = 100), following a 0.2 percent increase in November and a 0.6 percent increase in October.

A spokesperson for the Conference Board said:

… the LEI provides some reason for cautious optimism in the first half of 2012. This somewhat positive outlook for a strengthening domestic economy would seem to be at odds with a global economy that is losing some steam. Looking ahead, the big question remains whether cooling conditions elsewhere will limit domestic growth or, conversely, growth in the U.S. will lend some economic support to the rest of the globe.

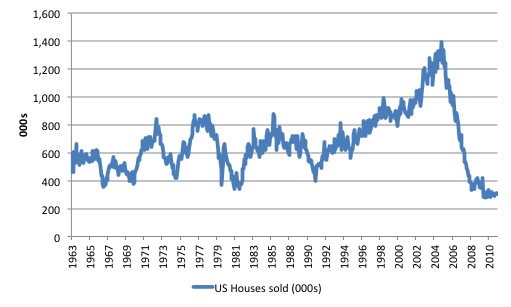

The other major US Census Bureau data release yesterday – New Home Sales – for December 2011 showed that:

An estimated 302,000 new homes were sold in 2011. This is 6.2 percent (±3.6%) below the 2010 figure of 323,000.

New-home sales fell in December 2011 and historical data from the US Census Bureau for New Residential Sales show that “total sales for 2011 were the lowest on records dating back to 1963”.

The following graph shows the history of new residential sales in the US since January 1963. It is stark reminder of the collapse in the housing market.

So the private domestic sector is still acting cautiously and seems more intent on running down the existing debt levels which is leading to relatively subdued consumption spending.

What explains the stark differences between the performance of the UK and US economies at present?

It is possible that some of the difference is due to the UK economy being more exposed to the Eurozone than the US economy. But this just highlights the different fiscal position currently being adopted by the respective national governments in each country.

My assessment is that the major difference between the two economies relates to the conduct of the government in each case. The UK government has been announcing its intention to impose harsh fiscal austerity on the national economy since the day it took office. The fact is that most of the spending cuts are still to come, which doesn’t augur well for 2012, the spending associated with the Olympic Games notwithstanding.

It is highly likely that the “announcement effect” by the government of its intention to harshly cut spending has further eroded confidence among households and business firms, already labouring under the deflationary burden of high unemployment.

By way of contrast, while there has been austerity rhetoric in the US, which is probably held back private spending, the unresolved nature of the current political impasse has not translated into any serious budget cuts to date. The current US regime is still talking job creation and growth, which is far removed from the rhetoric that emerges from the British government.

However, I do not want to suggest that the US government is demonstrating sound macroeconomic policy management. Rather that it hasn’t started to actively undermine private spending and overall economic growth in any major way.

If the political environment changes in 2012 or perhaps 2013 after the November election, and more conservative voices gain traction in actual policy settings, then the US will follow the route taken by many of the Eurozone nations and Britain – that is, back towards recession.

The current neo-liberal mantra that governments can successfully engage in a “fiscal contraction expansion” remains in my view an ideological assertion without empirical foundation. The only successful examples of nations growing out of recession when private spending has been flat and governments engage in fiscal contraction occurs when external conditions were favourable and export growth could compensate for the loss domestic demand arising from the reduction in government deficit.

As I explain in this blog – Fiscal austerity – the newest fallacy of composition – when austerity is the “flavour of the month”, that is, is broadly adopted, such growth opportunities are not sufficient to compensate for the fiscal contraction.

Which brings me to a short empirical discussion.

In November last year, the British economist of some note declared the US for example of an economy that that was successfully pursuing a “fiscal contraction expansion”.

The blog – expansionary fiscal contraction – was written by Paul Ormerod. I would add that I hold Paul in high regard and consider his 1994 book – The Death of Economics – to be one of the better books I’ve read about economics.

Paul Ormerod said:

To many people, this phrase is an oxymoron. How can fiscal contraction be expansionary? But the evidence suggests that this is exactly what has been happening in the United States.

So while I generally think his work to be interesting and thought-provoking, in this case I consider the data fails to support his contention about the “fiscal expansion contraction”. One might go further and so he is plain wrong.

When discussing the notion of a “fiscal contraction expansion”, we have to be sure that we’re not talking at cross purposes. when I conclude that such a notion is generally impossible to achieve I’m not saying that growth cannot occur if the government sector is reducing its deficit in discretionary terms.

Obviously when private spending is strong enough the public sector can contract without damaging economic growth. That is the reason Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) indicates that the time to make discretionary fiscal adjustments of a contractionary nature is when private spending growth is sufficient to keep overall nominal aggregate demand growing in line with real capacity.

So it becomes a matter of timing. Making contractionary fiscal adjustments at a time when private spending is still very subdued is likely to undermine private sector confidence and further damage the prospects of a private sector recovery.

Paul Ormerod says:

In terms of national output, GDP, the trough of the trough of the recession was reached in the second quarter of 2009 (2009Q2). We have now had nine successive quarters of positive growth, and in 2011Q3 the level of output is above that of its peak level before the recession started. Growth has not been as strong as would be desirable, but there has been consistent growth. On any measure, the recession is over.

All of which is correct. Although there is a debate in the profession about the appropriate definition of a recession. Paul Ormerod is using the definition based upon real GDP growth – which says a recession occurs when there are two consecutive quarters of negative real GDP growth. So in that sense the US recession was over more than 2 years ago.

There was an interesting discussion of these issues in this article (November 23, 2008) – What is the difference between a recession and a depression?. There you read that some economists consider “a more meaningful definition of a recession” to be “an extended period of below-trend or below potential growth”

However, given the difficulty of estimating trend real GDP growth, another popular rule of thumb is that a recession occurs “when the unemployment rate rises by more than a given amount over a specified period for example, by more than (say) 1½ or 2 percentage points in 12 months”.

The article says that “(s)uch an approach has the additional advantage of making sense to people with no training in economics, who quite reasonably do not know what GDP is, and who will probably not be able to tell when it is declining, but who certainly recognize a rise in unemployment when they see it”.

So on that basis the US economy is probably still in recession given the slow pace of unemployment rate retrenchment.

But in terms of the data I agree with the turning points in the US business cycle that Paul Ormerod identifies above.

From that observation, Paul Ormerod then says:

Where has the growth come from? Not from public spending! Between 2009Q2 and 2011Q3, current public expenditure in real terms fell by $38 billion, or by some 1.5 per cent.

The private sector grew, the public sector contracted. Private consumption rose by $450 billion, nearly 6 per cent, and capital spending by firms rose by $200 billion, or nearly 13 per cent. There was a slight deterioration in the net export position, but overall the private sector delivered growth.

I could quibble about the actual figures here but that is not going to be the point of contention. You can get detailed National Accounts tables for the US from the US Bureau of Economic Analysis.

In fact real personal consumption rose between 2009Q9 and 2011Q3 by $US435 billion (or 4.8 per cent); real private investment rose by $US385 billion (27.7 per cent), Net exports fell by $US71 billion (21.4 per cent); Total Government spending fell by $US38.4 billion (1.5 per cent) and Federal Government spending rose by $US34.5 billion (3.4 per cent).

Now the disagreement enters.

To extend the example I thought it would be interesting to compare Ireland with the US, given that Ireland was one of the first economies to embrace the austerity approach (as early as January 2009) while private spending was still contracting. The NIPA data for Ireland is available from the Irish Central Statistics Office.

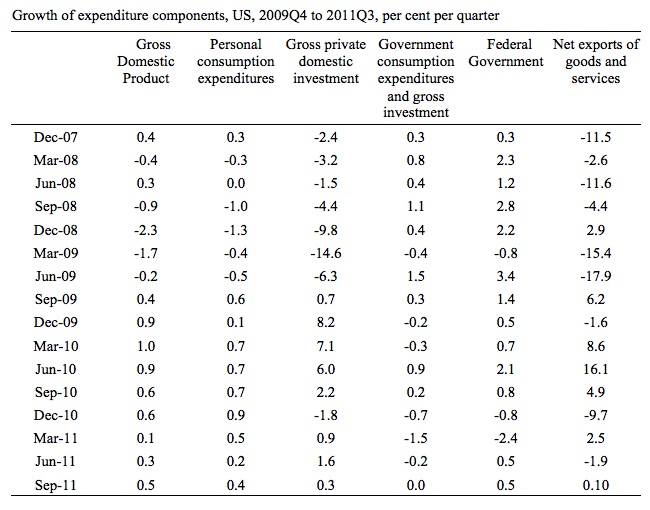

The US data comes first.

The following Table shows the growth in the major expenditure components contributing to real GDP from the peak December 2009-quarter to the latest available data (September-quarter 2011).

You can see that with some exceptions that total government spending continued to grow until the 3rd quarter 2010. Growth in federal government spending was relatively strong until the December-quarter 2010.

If you juxtapose that with growth in real GDP (column 2) then you can see the government spending growth was positive just before the turning point and just after. Equally, government spending growth was still positive as private spending growth shifted from negative to positive territory.

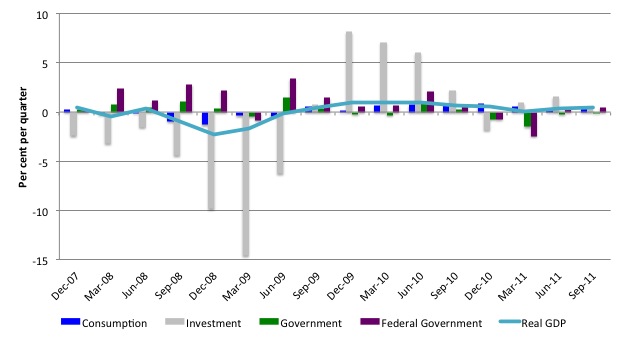

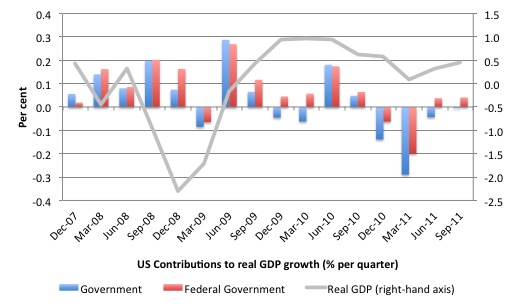

The same data appears in graphical form as follows.

The following table shows the contributions (in percentage points) to real GDP growth from the various expenditure components.

You can see that during the period of private contraction, the government contribution was almost always positive (there was one quarter, March 2009, when the government sector contributed to the negative GDP result).

The important observation is that the government sector mostly contributed to overall growth even after private spending growth was also making a positive contribution.

The following graph is based on of the columns from the previous Table. As private sector spending collapsed and real GDP growth fell the contribution from the government sector was positive (barring one quarter).

It’s also interesting to note that once the contribution of the government sector started tapering and then went into negative territory the overall real GDP growth right in the US began to fall.

The US situation is clearly complicated by the fact that the state governments were contracting while the federal government was trying to stimulate the economy. It was only the strength of the federal stimulus that ensured that the overall contribution of government to real GDP growth was mostly positive at the crucial time when private sector spending was contracting.

I do not believe you can argue that the US economy recovery occurred when both the private and public sector spending was contracting. That is clearly not consistent with the evidence.

It is obvious that if the federal government had compensated the state governments for their lost tax revenue (and averted the cuts in state spending), then the collapse in real GDP growth could have been largely averted.

The overall fiscal stimulus (the consolidation of state and federal initiatives) was clearly inadequate and that is the reason that unemployment rose so sharply and has endured for so long and its elevated level.

It’s interesting to compare the US experience with that of Ireland.

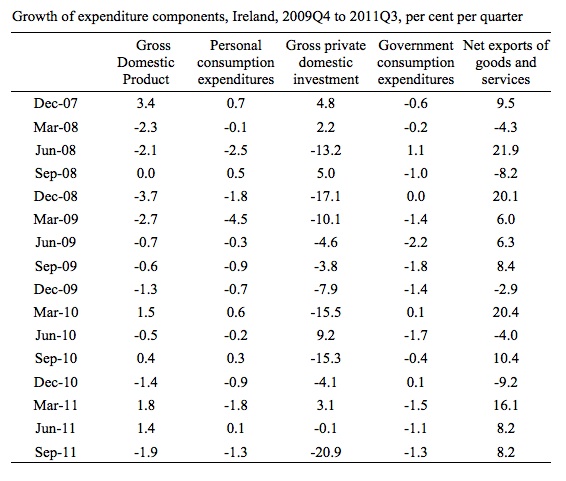

The following table shows the quarterly growth in the major expenditure components in Ireland from 2009Q3 to 2011Q3.

The way the Irish Central statistics office presents its national income data makes it difficult to disentangle public and private investment. So the government spending in this Table relates to its public consumption spending (that is, current goods and services) and the gross private domestic investment data refers to economy-wide spending.

The Irish economy began to contract in the first-quarter 2008.

It is clear that as private spending began to contract, and, in the case of private investment, contracted sharply, government spending was also contracting. In other words, the fiscal contraction was coincident with the private contraction.

This is the “fiscal contraction expansion” scenario and is unlike what happened in the US.

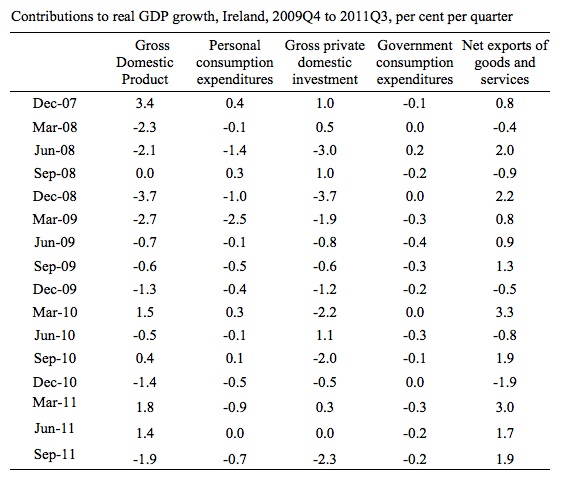

The following table shows the contributions to real GDP growth of the major expenditure components from 2009Q3 to 2011Q3. You can see that the contribution from the government sector has been negative or zero for all but one of the quarters since December 2007 and then it was a miserly 0.2 percentage point contribution.

The negative public contribution has consistently reinforced the ongoing negative profit contribution.

Conclusion

When we are considering the contribution of government spending to real GDP growth we should always form our assessment relative to what the other components of aggregate demand are doing.

If you observe real GDP growing at a time when public spending is contracting, then you are not entitled to conclude, without other information, that fiscal austerity is expansionary.

For fiscal austerity to be expansion, the other components of spending has to be positive and reacting to the fiscal cutbacks in a positive manner.

History tells us that this rarely happens and does not happen when there is widespread fiscal austerity damaging export markets.

Premature fiscal cutbacks are likely to further damage fragile private sector confidence and entrench the malaise in overall spending. Ireland is a perfect example. The British economy appears to be following suit.

Conversely, the US government contribution was positive (mostly) as private spending was declining and one could say the maintenance of that positive contribution extended beyond the turning points in private spending growth, which helped restore some semblance of a positive outlook in the US economy.

Once private confidence improves and spending decisions reflect that optimism then public spending can begin to contract without pushing the economy back into recession.

But until private spending is strong enough, public spending should continue to support aggregate demand expansion. If public spending contracts to early in this environment then real GDP growth will start to decline. The US is a perfect example of that. Paul Ormerod is correct that there has been 9 successive quarters of growth in the US, even though public spending growth has started to decline (and become negative).

But he might have also pointed out that as the public spending growth has moved into negative territory so has the real GDP growth rate.

Saturday Quiz

The Saturday quiz will be back again sometime tomorrow – about the same level of difficulty as always.

That is enough for today!

I’ve been watching the CEO’s of different companies as they come on the news networks and it is amazing how many of them I hear calling for a balanced budget. When it comes to the government they seem to all be reading from the same book and I wonder if it is because of their educational background. How can so many people walk in lockstep in the wrong direction with so few strays? Maybe it is just me. But, I do want to point out that a lot of the CEO’s seem to be optimistic about the US and most of the world – except Europe. Even with their downbeat assement of Europe, from what I have learned here, I suspect that they are too optomistic about Europe anyway.

I also think that Steve Keen’s “debt accelerator/decelerator” analysis could help explain things as well. The private sector in the US is hugely over-leveraged with debt and the initial plunge in the Great Recession was from a sudden loss of momentum and the start of a trend to pay down that debt. The accelerator turned negative, velocity turned negative, and debt stocks started to fall.

Firms and individuals are still paying down that debt, but while the velocity may still be negative (stocks are decreasing), the acceleration has returned to positive and the stocks are decreasing at a lower and lower rate. It’s also possible that private debt is accumulating again, but it can only be temporary–essentially, if growth in the US private sector is resuming without paying down all that debt, it’s likely that we’ll simply hit the exact same point again and have another big drop.

The situation could also be that the acceleration will fluctuate between negative and positive in cycles, slowing and increasing the downward trend in debt stocks and providing the illusion of positive and negative growth over time. Sort of a rollercoaster effect to the bottom vs. a sudden drop.

According to the 4th Qtr US GDP, much of the growth was caused by inventory accumlation. This is what happened in the UK in the 3rd Qtr when unemployment started to rise. I think that the recent fall in US unemployment will stop roughly where it is now, and stay their until further fiscal support is provided, or until the private sector reduce their debt levels and start spending again.

Given Bolo’s comments above though, more fiscal support might be the only way to get unemployment going down again.

So Paul Ormerod might be speaking prematurely.

Bill,

Is not the different USA vs UK experience down to the political cycle (trick cyclists?).

Obama seeks re-election so needs unemployment to fall even if the jobs available are lower paid.

UK Tories are following their small government agenda, attempting to privatise what is left (NHS?) and use the EZ , bond vigilantes etc to cow the UK population to achieve these ends, Personally I await the SNP highlighting UK Gov.,BoE & Treasury antics in preventing growth/employent in Scotland (and by inference the whole of the UK) in the referendum campaign.

Dear ChrisLongs (at 2012/01/28 at 4:50)

I would agree with your assessment. But that doesn’t alter the point that the government support or otherwise for aggregate demand at crucial points in the private spending cycle is important. Your point extends to motivation for the support or withdrawal of the support.

best wishes

bill

Bill,

Thanks for your reply – I must admit to a feeling of hopelessness with regard to UK politicians at present which may have coloured my original comment.

I would support a job guarantee scheme especially for under 25’s but despair that any UK politician is capable of making the necessary arguments for its implementation.

I would forsee the following advantages to such a scheme:

more social inclusion/cohesion

less youth crime

increase in demand & subsequent growth

Thanks for a thought provoking blog.