For years, those who want selective access to government spending benefits (like the military-industrial complex…

The British government can never run out of money

Last week, the UK Office of National Statistics released their – Second Estimate of GDP Q4 2011 – which updates (once more information is available) the flash estimates that were released recently. The information confirms that the British economy went backwards in the fourth-quarter 2011 and confirmed that the September quarter 2011 growth was overestimated and the latest publication revised that downwards from 0.6 per cent to 0.5 per cent, a small revision but downwards nonetheless. There is now a real prospect of the economy entering a double-dip recession. The British government is now under pressure to revise its current budget strategy in order to prevent that probability. However the response of the British government (courtesy of the Chancellor) is to defend its ideological position with outright lies. The Chancellor claims that the British government can do nothing about the slide into recession because it is run out of money. Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) demonstrates its impossibility of that event occurring from a financial perspective. What the Chancellor really is telling the British people is that the government refuses to stop unemployment rising. Why the Opposition and the Press are not exposing these lies is a further problem.

In the Statistical Bulletin – Second Estimate of GDP Q4 2011 we learn that:

- UK real GDP decreased by 0.2 per cent in the December-quarter 2011.

- Production sector output fell by 1.4 per cent – and manufacturing fell by 0.8 per cent.

- Output of the service industries was flat and construction sector output fell by 0.5 per cent.

- Real household final consumption expenditure rose by 0.5 per cent in the December quarter.

- Real wages fell in the December quarter.

While the ONS chose those items to emphasise in their “Headline Figures” the other important result was that the data confirms that the government’s fiscal austerity strategy has not yet impacted on its own contribution to real GDP growth which was positive in the December-quarter 2011.

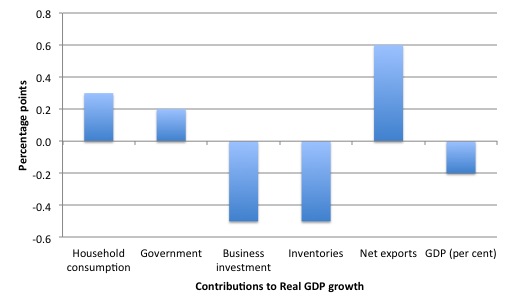

The following graph is taken from the ONS data and shows the contributions to real GDP growth (in percentage points) of the main expenditure aggregates in the national accounts.

After Household consumption made a positive contribution to real GDP growth (0.3 percentage points) after recording negative contributions to the previous three quarters. I will come back to this soon.

The government sector (consumption expenditure) also made a positive contribution to real GDP growth although this contribution slowed in 2011 (0.3 per cent – compared to 1.3 per cent in 2010).

Business investment declined by 5.6 per cent in the December-quarter 2011 and was more than 20 per cent below the peak reached before the crisis.

The UK Press Association put out a report today – ‘Debt noose tightening’ on families which documented recent evidence prepared by the UK Consumer Credit Counselling Service (CCCS) in its publication – Consumer Debt and Money Report.

The data indicates that:

The “interest burden” recorded for the last three months of 2011 equates to almost a quarter (24%) of incomes after regular bills are paid … This share rose by 0.1% from the third quarter of last year as living cost hikes outstripped wage increases …

The Report also suggests that while the heavily-indebted UK households have been trying to “pay down their debts” this capacity “has been slowing as disposable income” has been squeezed by rising “inflation, with expensive petrol, utilities and housing costs and deteriorating employment conditions”.

There was a comprehensive report issued by the Bank of England – The financial position of British households: evidence from the 2011 NMG Consulting survey – in their Quarterly Bulletin (2011 Q4).

The accompanying database is a font of information but large (19 mgbs)

The Report noted that:

61% of households reported that they did not intend to change the amount saved each month. Of the others, a larger share of households were planning to increase saving (22%) than were planning to decrease saving (16%). That means that the net balance of all households planning to increase saving was positive.

But of those who said they would not be increasing their saving:

The most common reasons given by households intending to reduce saving were that households could not save as much each month, either because of the higher cost of essential items, or lower household income

None of this evidence supports the mainstream Ricardian story that households have increased their saving to pay for expected future tax increases (to “payback” the rising budget deficits) and would unleash a new round of spending (that is, reduced its saving) once the government began its deficit reduction plan.

The evidence is that in the face of income constraints arising from unemployment households find it hard to save.

The rising unemployment in Britain will further erode the capacity of British households overall to save,

In this blog from 2010 – I don’t wanna know one thing about evil – I published the results of some research I did on the the official British Treasury documents from the Budget 2011.

The main Budget document discussed the “unsustainable levels of private sector debt” and the need to reduce the vulnerability of households.

This discussion was in the context of a vulnerable and unbalanced economy relying too much on private sector indebtedness for growth and being very sensitive to housing price movements.

It is clear that a growth strategy that relies on the private sector increasingly funding its consumption spending via credit is unsustainable. Eventually the precariousness of the private balance sheets becomes the problem and households (and firms) then seek to reduce debt levels and that impacts negatively on aggregate demand (spending) which, in turn, stifles economic growth.

When those adjustments are stark – as they have been in the recent financial crisis – especially when housing prices collapse – the consequences are wide-ranging and very damaging. A recession induced by a private debt crisis is usually deeper and harder to resolve than a downturn arising in the real sector from, for example, a loss of consumer confidence.

The dominant discussion in the 2011 British Budget papers was about the evils of public debt and the need to reduce it. The justification for the harsh austerity program proposed is all tied up in the public debt arguments.

What you discover if you dig deeper into the supporting documents (as outlined in that blog) is that while the British government claimed it was aiming to restore “strong, sustainable and balanced growth” it was relying on a boost from the private consumption and the external sector.

One paper from the British Office of Budget Reponsibility (OBR) (published April 21, 2011) – Household debt in the Economic and fiscal outlook – revealed that:

Our March forecast shows household debt rising from £1.6 trillion in 2011 to £2.1 trillion in 2015, or from 160 per cent of disposable income to 175 per cent. Essentially, this reflects our expectation that household consumption and investment will rise more quickly than household disposable income over this period. We forecast that income growth will be constrained by a relatively weak wage response to higher-than-expected inflation. But we expect households to seek to protect their standard of living, relative to their earlier expectations, so that growth in household spending is not as weak as growth in household income. This requires households to borrow throughout the forecast period.

The OBR also said that “net worth is forecast to decline as a percentage of income as the household debt ratio is expected to rise and the household assets ratio is expected to fall”.

In other words, while the British government was warning about the unsustainable household debt levels its fiscal austerity program (once it really bites) is reliant on the private sector taking on a rising debt burden over the forecast period and becoming relatively poorer?

Has household consumption turned the corner? One commentator (a bank economist) in the Guardian article (February 24, 2012) – UK GDP figures: what the economists say – said;

… the strength of consumption is a hawkish signal … Consumer spending has shrugged off the weakness in confidence and the squeeze on disposable income when it was at its most intense (as inflation peaked above 5%). Against that background, growth could have been a lot worse … with the headwinds facing the consumer subsiding (as UK inflation has slumped), it is likely to be onwards and upwards from here for the biggest component of GDP by expenditure.

It is true that inflation is now moderating in the UK and this has eased the real squeeze on disposable income.

But I do not consider that the “headwinds facing the consumer” have subsided to the point that a renewed spending boom is ahead in the face of tightening austerity.

As the graph above shows, the fiscal austerity is yet to impact directly. The contribution from the government sector remains positive even though growth is going backwards.

If the government contribution had have been zero in the December-quarter 2011, then real GDP growth would have been -0.4 per cent. It is much more likely that the household sector chose the Xmas period (and the sales that followed) to bring forward consumption at the heavily-discounted prices.

The proof is in the pudding but as unemployment rises and the contribution of the government sector turns negative as the austerity plans bit further then it will hard for heavily-indebted households to maintain robust consumption growth.

The clear sign that forward-looking behaviour is predicting deteriorating conditions is to be found in the 5.6 per cent decline in business investment. Firms only invest if they think they will be able to profitably employ the new productive capacity that they will create.

The decline in investment in the year to December 2011 indicates that British firms are not confident that aggregate demand is likely to be robust and growing in 2012 and beyond.

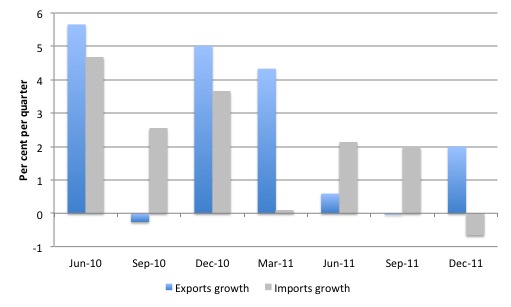

The following graph shows the quarterly growth in exports and imports (current prices) from June-quarter 2010 to the December-quarter 2011. In the December quarter, import spending fell by 0.7 percentage points while exports spending rose by 2 per cent.

So while net exports have improved the message is not unambiguously good given the import contraction.

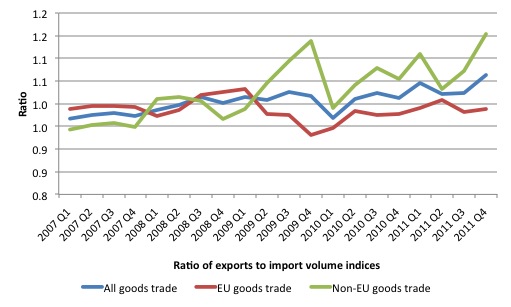

The next graph shows the external sector performance in terms of the ratio of exports to import volumes. The data shows that this ratio has improved towards the end of 2011 but “almost wholly due to the strengthening of trade performance with non-EU countries” (see The UK Office of National Statistics Economic Review – February 2012).

With the currency depreciation, it would be surprising if this ratio had not improved. Imports are also likely to be declining not only because of the relative price effects (exchange rate changes) but also because of the slowing economy and the collapse of business investment.

So when the external contribution to real GDP growth rises we always have to temper our enthusiasm if some of that change is due to a decline in imports.

But the overall point is that the external sector is still not contributing enough to overall demand to maintain growth. Unemployment will still rise and I suspect that will choke of any recovery in consumption.

Given the poor news overall, what would a responsible government response be? It would certainly be different to the response provided to the media by George Osborne.

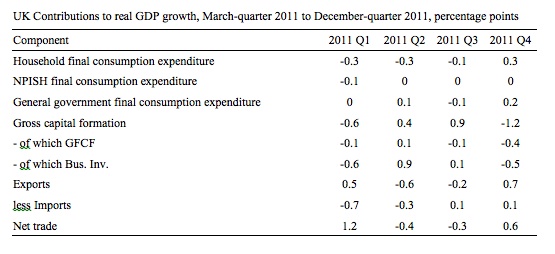

The following Table shows the contributions to real GDP growth of the main expenditure items for the four quarters of 2011.

Overall, real GDP growth has declined from 1.7 per cent in 2010 to 0.6 per cent in 2011.

It is clear that the impacts of fiscal austerity are yet to be felt.

In the UK Daily Telegraph article (February 26, 2010) – Osborne: UK has run out of money – we read that the UK Chancellor George Osborne is not intending to reverse the direction of government policy:

In a stark warning ahead of next month’s Budget, the Chancellor said there was little the Coalition could do to stimulate the economy.

The economy is now teetering on a double-dip recession as a result of a slowdown in spending

British government could immediately alter the situation by abandoning plans for a negative public sector contribution to real growth.

The dramatic fall in business investment is the first sign that the impending austerity is damaging domestic demand.

However the Chancellor disagrees and thinks that the “best hope for economic growth” was for business to increase investment. The question he doesn’t answer is why would firms take that risk in the current climate.

Osborne then rationalised the Government’s position in this way:

The British Government has run out of money because all the money was spent in the good years … The money and the investment and the jobs need to come from the private sector.

Which of-course is an outright lie. The British government can never run out of “money” – it is sovereign in its own currency. I wonder why the press and the Opposition didn’t accuse the Chancellor of outright lies.

Whether the British government should be spending more “money” is not a question relating to its financial capacity (which is infinite) but rather has to be considered in terms of the overall state of aggregate demand in the economy.

With unemployment rising and real GDP growth now negative there is a prima-facie case to be made for more government spending.

It might be that net exports could fill the spending gap left by the collapse of business investment. In other words, our reorientation of the economy towards external activity away from domestic activity may allow the government to avoid taking a stronger spending role in the economy.

However the data shows that while net exports made a positive contribution to real GDP growth, that contribution was insufficient. Further, is unlikely that Britain will enjoy an export-led recovery of sufficient proportions to see significant reductions in its unemployment rate.

And it is also unlikely (and ill-advised) that Britain will enjoy another house of consumption binge of sufficient proportions to justify a contraction of public spending.

Whether it was advisable to run deficits in the “good times” is quite a separate question from the need to run them now. The only temporal link that allows one period’s fiscal position to be assessed against the next period’s position is the impact the past budget has had on the next period’s real economic performance.

In that regard, if the past spending had pushed the British economy into a inflationary situation (that is, nominal demand was growing much faster than the real capacity of the economy to produce), then one might say, other things equal, that the current budget should start to ease the inflationary pressure.

.

But at present, with inflation moderating and real growth heading south, such an argument cannot be made.

The Telegraph story reported that the Chancellor:

… would stand firm on his effort to balance the books by refusing to borrow money.

Conclusion

The question is now whether the decline in British business investment (driven in part by the slowdown in manufacturing) and the improvement in its exports will persist.

With growth now negative, the incentive to firms to increase business investment would appear to be low. They will be able to satisfy the current demand with existing capacity.

I don’t consider the brief return of solid consumption growth to be sustainable as unemployment continues to rise. Thus if government net spending does move closer to balance and the contribution of the government sector becomes negative then the British economy will likely move into a double-dip recession.

But the most extraordinary aspect of all this is that the British Press and the Opposition allow the Chancellor to lie to the British people without sufficient scrutiny.

It might be a matter of opinion whether the outlook for the British economy is positive or negative (I fall on the negative side), but it is a matter of fact that the British government can never run out of money.

For public debate to be conditioned by such lies is a testament to the dominance of mainstream economic thinking, which created the crisis in the first place, and the unwillingness (weakness) of the press to prosecute the myths that define that way of thinking.

That is enough for today!

I had a look for some crumbs of comfort in the figures reported last week and about the only one I could find was that gross government expenditure was still high in absolute terms and pretty much the highest its ever been in deflated terms.

And the driver for that was increased net social benefits – the automatic stabilisers at work again.

Hopefully the timing mismatch between taxation and spending means that the amount shown to come out of the economy relates to the better periods early last year and that the automatic stabilisers will reduce the tax take as well in future months.

“The British government can never run out of “money” – it is sovereign in its own currency”

Indeed, and I am sovereign in my own currency. I can write IOUs to my hearts content, right up to the point where people refuse to take my IOUs any more, because I don’t deliver on them. The UK government could indeed ‘print’ money if it so wished (some might say it already is), but to say it can never run out of money is arrant nonsense. It runs out of money at the point where nobody will accept their ‘money’ for goods and services, because they have no faith that they in turn can use it to buy other goods and services themselves.

Dear Jim (at 2012/02/27 at 21:28)

And in what currency will all these citizens/corporations etc who have lost faith in the Sterling be paying their tax obligations to HM?

Or is Britain going to see a mass exodus of its citizens?

best wishes

bill

MMT is logically and formally consistent and it is standing up to the empirical tests being conducted in the world laboratory of modern ideological idiocy. Every time MMT says things will get worse if you apply neoclassical economics, MMT’s predictions are being borne out.

Without minimising the hard work of MMT theorists (simple conclusions and succinct formulas often take years of hard work to arrive at), MMT ultimately boils down to one fundamental insight. Money is notional. The corollary (in my opinion) is that material/energetic resources are real.

Whilst it is true that neoclassical austerity is knocking a flat economy on the head, it is also true that high energy costs are doing the same thing. Energy costs come in two forms namely money cost (which is notional) and energy cost as energy returned on energy invested (EROEI). It is the second real cost that will become the real story in the next few years (although it will still be misinterpreted by the mainstream as a financial cost issue).

A combination of MMT economics and a dirigisme approach to developing a non-fossil, non-nuclear, renewables economy might still save us if we could globally bend all our efforts to these goals while stablising world population and avoiding wasteful wars and conflicts. I wish I could believe this will actually happen.

Jim, a recession is caused by an increase in the demand for the government’s IOUs.

Dear Bill,

One assumes that Zimbabwe was able to continue printing money ad infinitum then, with no adverse effects, because the citizens always had need of those trillion dollar notes to pay their taxes? And similarly in Weimar Germany? Or have those little examples been erased from the MMT history books?

Jim.

Jim,

For information about Zimbabwe, Weimar etc and hyperinflation see the following links:

Zimbabwe for hyperventilators 101

Printing money does not cause inflation

Wir wollen Brot!

Kind Regards

Jim, Jim, sigh, poor Jim:

Do yourself a favor and search on this site for a few seconds. Try some keywords. Be creative.

Zimbabwe, Weimar, been there, done that. Getting tiresome having to repeat over and over when the answers are right at your literal fingertips.

Bill,

Jim’s persistence, above, is but another bit of evidence to support my past suggestions that someone has to explain MMT using visual as well as written and oral communication strategies. Animation, cartoons, comic strips, etc. are tools to communicate with a large portion of the population (some of whom may be wedded to Austrian, neoclassical, or other economics concepts while others may simply have no familiarity with economics theory). When a society pretends to depend upon an educated electorate among the masses, every mode of communication will be required to participate at the voting booth in an intelligent manner.

By the way, Tom Hickey posted a photo of the audience at the educational forum in Italy over at:

http://mikenormaneconomics.blogspot.com

‘Stephanie Kelton

@deficitowl

tweets:

Here’s a partial view of the bankers’ worst nightmare that is here in Rimini, Italy learning about #MMT this weekend.pic.twitter.com/K9CKa6I6

(h/t Scott Fullwiler via Twitter)’

Unfortunately, not everyone has an opportunity to attend such educational events.

Zimbabwe ‘s problems revolved around a collapse in the real economy, the printing of money was a desperate symptom of this, not its cause.

Bill -as a retired engineer/business man, now writer, I was tempted to answer your filter with the correct arithmetic, while adding a rider “except if you’re a banker; then it can amount to anything you want!”

Since 2008 – 9 I have followed your blogs on MMT and in, general agree, it is potentially a far more logical and engineered system than the self serving bodge up we are suffering under.

My main concern, and this relates to any system, is the innovative ability of humanity to take an inch of opportunity and turn it into a mile of exploitation. In essence this exactly the exploitation which has corrupted the present financial model.

Can you highlight the restraints in MMT that would prevent for one instance, the political bag-men printing, pumping and spinning a nations GDP in order to get re-elected?

Prior to reading your post I was researching LIBOR rates in relation to interest charges on retail/consumer EAR rates. Pre – meltdown 2006 -2009 Libor was running around 5.5%, retail consumer @ 1.22 monthly, business 1.1 (these went up around 17 p/point 2007 and another 10 2008. Then stabilised in 2009 after a further 10p/p rise which continues to this day.

2009 was when the BoE introduced the 0.5% base rate which again continues and LIBOR has settled from an initial 0.55 to around 1.8%.

While I appreciate the risk factor on consumer and medium business, it seems pretty obvious the banks are crucifying the small/medium business and their consumer customers while pocketing the increased margins between interest costs and those charged.

Apart from further propping up the banks, is there any economic sense in support of this?

Ikonoclast, I agree with your comment with the exception of the “non-nuclear, renewables” bit.

Renewables can’t provide base load power reliably except at prohibitive cost and environmental damage.This is because the energy source is unreliable and requires a massive investment in storage and long transmission lines. Advocates of renewables and the anti-nuclear lobby are the best friends the fossil fuel industry has.

Safe,clean,reliable nuclear power plants can be built on the sites of present day coal burners and plug into the existing grid. Existing technology in Generation 3 reactors is being utilized in many nations to reduce and eventually eliminate the toxic contamination resulting from burning fossil fuels and this includes gas. Generation 4 reactors now in the development phase will burn the current stocks of waste nuclear fuel and use uranium or thorium at about 150 times the efficiency of current reactors. The waste produced by these reactors has a much shorter hazardous life (about 300 years maximum) and the waste is of much smaller volume.

Because of the efficiency of Gen 4 reactors the fuel supply is expected to last to thousands of years in the future. By contrast,if we continue on our present course we very likely won’t have a civilization 100 years in the future.

CharlesJ, thanks for those links. For the first time I am starting to get a sound understanding of hyperinflation. It always bugged me how the Japanese could massively increase the money base, yet the broader money supply would barely grow and price inflation go nowhere for long periods of time. It seems that AD must exceed AS before hyperinflation is even possible. Continuing to learn a lot from this excellent blog.

Cheers!

As a non-economist, it strikes me that UK and other governments are increasingly dumping “risk” on to the shoulders of private individuals (particularly those least likely to be able to bear the burden).

The best example of this is Greece. To avoid a disorderly state default, Greece has been forced to accept an austerity package that’ll mean many of its citizens won’t be able to afford to meet essential costs of living (food, housing, medical care etc). Instead of a defaulting state we’ll have huge numbers of desperate individuals defaulting on what they owe and social meltdown – why is that a preferable situation?

MMT stars: http://www.counterpunch.org/2012/02/27/our-very-own-oscar-night-in-rimini/

I have added a few blogs at

http://pshakkottai.wordpress.com/2012/02/26/misunderstood-deficits/

http://pshakkottai.wordpress.com/2012/02/27/national-debt-and-national-wealth-compared/

to show “Cumulative Govt deficit becomes Gross national wealth. Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) is correct! “Unsustainable debt” is just nonsense.”

@Esp Ghia

Learning information so contrary to everything we’ve been taught is rather exhilarating, isn’t it? Even the Federal Reserve has acknowledged the size of the Monetary Base does not correlate with the behavior of the Money Supply.

http://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/feds/2010/201041/201041pap.pdf

Great post Bill. There does seem to be a real misconception about how monetary policy works, and what actually causes inflation. Hyperinflation is really a complete collapse in confidence in the sovereign, that’s what Zimbabwe and Weimar were about. The type of QE – or “printing money” we are talking about is something quite different. Look at Japan – how much QE have they tried in the last 20 years, and they are STILL mired in a deflationary spiral. Or, to take the US as another example. The FED’s balance sheet may be at all time highs, but because the transmission system between the banks and the real economy has been broken – people do not want to borrow and banks have not wanted to lend – the banks take the money they receive from QE (i.e. selling their bonds to the FED), and much of it simply stays on deposit at the FED. If anything, one might say that the BOE and the Treasury should work together. The BOE should purchase enough debt issued by the Treasury to allow for a stimulus program that is large enough to fill the gap in aggregate demand caused by the deleveraging in the private sector.

The chart in this link also implies the money multiplier is bogus – it shows M1 growing faster than M2 in the US and also tries to estimate M3 (which is growing slower still). It looks like US banks have taken the excess liquidity provided by the Fed and, for a host of reasons including tighter lending restrictions, impaired balance sheets and poor loan demand, placed the surplus funds back on deposit with Fed. Does that sound right from an MMT perspective?

http://www.shadowstats.com/alternate_data/money-supply-charts

Esp Ghia,

The Fed is currently paying 25 bps interest on reserves, so banks are keeping them on deposit. They really don’t have much choice because the Fed’s board of governors doesn’t yet seem to understand that pumping up liquidity doesn’t increase banks’ capacity to make loans. Normally banks would compete to loan out their excess reserves to other banks, but as we’re already against the ZLB the only way they can earn a profit on their current reserves is to hold them and collect interest from the Fed.

Ikonoclast (February 27, 2012 at 22:50)

Podargus beat me to it. To many (most?) physical scientists the answer to energy supply is nuclear power, and this is every bit as obvious as MMT may be to you. In this century nuclear power will bring an end to the high cost of energy … and allow people everywhere the technical means to attain a high standard of living. Whether we do it, or continue to treat each other like crap remains to be seen.

http://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/feds/2010/201041/201041pap.pdf is a very good read. I recommend it to anyone. Thanks Ben Wolf.

” If anything, one might say that the BOE and the Treasury should work together.”

Which they could do if we stop this silly pretence that the central bank is ‘independent’ of government. It is no such thing.

The central bank should be operated at board level by a parliamentary committee and the government should just ‘borrow’ from the central bank. Which then amounts to the government asking parliament for approval to spend – which is at it should be.

“Because of the efficiency of Gen 4 reactors the fuel supply is expected to last to thousands of years in the future. ”

With cleaner nuclear – both fission and fusion – the problem shifts to the planetary heat balance equation. The one advantage of renewables is that they don’t affect the heat balance of the planet. What comes in from the sun is converted to usable energy.

Nuclear is like fossil fuels in that it liberates energy from matter – which adds heat to the system without adding any extra cooling capacity.

So even with nuclear we will eventually cook the planet. Which means along with nuclear we need to work hard on energy efficiency – or a planterary sun shade 🙂

The Iran nuclear crisis demonstrates that it will never be as simple as nuclear bringing “an end to the high cost of energy …allowing people everywhere the technical means to attain a high standard of living.”

Nuclear is highly, highly dangerous and anyone with the potential to create nuclear energy has the potential to develop nuclear weapons.