It's Wednesday, and as usual I scout around various issues that I have been thinking…

The Eurozone has failed – time for an orderly retreat

The voice from the parallel universe announced that “The euro as a currency is a great success indeed … it is backed by remarkable fundamentals” and harsh fiscal austerity is “the best way to get sustainable growth and job creation”. The only problem is that the voice was none other than the retiring ECB boss Jean-Claude Trichet as he prepared to retire from his post in October 2011. During his term, Trichet was constantly preaching how the introduction of the Euro was a “success”. The only problem is that it is hard to reconcile that conclusion with an examination of the actual data. The Eurozone has failed and an orderly dismantling of the entire monetary system with a return to floating sovereign currencies is the only way that any semblance of prosperity will return.

The former ECB boss would undoubtedly argue that the ECB’s success lay in stabilising the inflation rate. But there was nothing particularly unique about the Eurozone in that respect.

Trichet and his ilk would argue that the ECB’s approach to inflation targeting has several advantages over previous monetary policy approaches. Many of the alleged gains are attributed to the fact that inflation targeting allegedly provides the central bank with the independence it needs to be credible, transparent and accountable – essential conditions for an effective policy regime.

The enhanced policy credibility allegedly allows a higher sustainable growth rate. The enhanced central bank independence overcomes the time inconsistency problem whereby an inflation bias is generated by the pressure the elected government places (implicitly or explicitly) on non elected officials in the central banks to achieve popular outcomes. Thus inflation targeting can allegedly lock in a low inflation environment.

It is also often argued that inflation targeting not only reduces inflation variability but also reduces the variance of output growth. If certainty in monetary policy generates more stable nominal values, it is argued that lower interest rates and reduced risk premiums follows. This allegedly stimulates higher real growth rates via an enhanced investment climate.

Further, inflation persistence is allegedly reduced because one time shocks to the inflation rate are quickly eliminated by the policy coherence. The reduced inflation variability allows more certainty in nominal contracting with less need for frequent wage and price adjustments. This in turn means less need for indexation and short-term contracts.

However, the implications of this are a flatter short-run Phillips curve. In other words, higher disinflation costs – more unemployment and real GDP losses.

How large are the output losses following discretionary disinflation? Can these output losses be attenuated by the design of the monetary policy? The conservatives argue that the losses are minimised if the disinflation is rapid. The credible research literature shows that the losses are inversely related to the speed of disinflation.

There is also no credible empirical research which shows that a more politically independent central bank can engineer disinflations with attenuated real output losses.

The evidence is that while inflation targeting does not generate significant improvements in the real performance of the economy, the ideology that accompanies inflation targeting does damage the real economy because it embraces a bias towards passive fiscal policy which in our view locks in persistently high levels of labour underutilisation.

Disinflationary monetary policy and tight fiscal policy can bring inflation down and stabilise it but it does so at the expense of creating and maintaining a buffer stock of unemployment. The policy approach is seemingly incapable of achieving both price stability and full employment.

An examination of the research literature suggests that inflation targeting has not been effective in achieving its aims. This is despite the constant claims by the proponents to the contrary. Only a minority of the research literature supports the contrary view.

The most comprehensive and rigorous work on the impact of inflation targeting shows that it does not deliver superior economic outcomes (mean inflation, inflation variability, real output variability, long-term interest rates).

Considered in isolation, inflation targeting does not appear to make much difference. It is certainly hard to distinguish it from non-inflation targeting countries, especially those which have adopted the broader fight inflation first monetary stance, such as the US.

But the real damage comes from the discretionary fiscal drag which is the ideological partner to inflation targeting.

Please read my blog – Inflation targeting spells bad fiscal policy – for more discussion on this point.

Which brings me to a very interesting Bloomberg Op Ed today (April 2, 2012) – Euro Was Flawed at Birth and Should Break Apart Now – written by one Charles Dumas, who works for a London-based macroeconomic research organisation.

He writes that:

Since the launch of the euro in January 1999, Germany and the Netherlands have experienced a growth slowdown and loss of wealth for their citizens that would not have happened had they never joined the euro.

We know this to be true, because we can compare the progress of these two Northern European economies with that of Sweden and Switzerland, which kept their freely floating currencies in 1999 and continued to grow as before. Indeed, over the period of the euro’s existence, the German and Dutch economies have grown significantly more slowly than those of the U.S. and the U.K., despite the debt crisis now engulfing the “Anglo-Saxons.”

While the counter-factual (whether Germany and the Netherlands, two of the Eurozone “powerhouses” would have grown faster without the Euro) is difficult to be conclusive about, the fact that two non-Euro, EU nations and the big two Anglo-nations (both of which have been hit hard by recession) have outperformed the EZ powerhouses is hard to argue against.

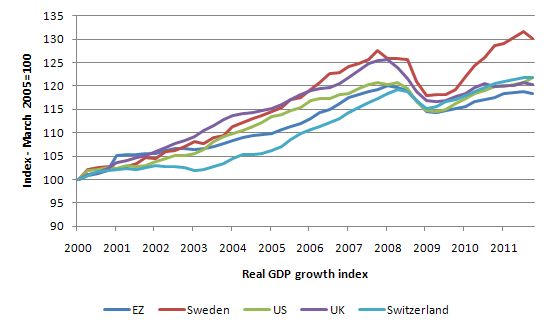

Consider the following graphs taken from National Accounts data available from the Eurostat database. The first graph shows in index number form (March 2000 = 100) the quarterly growth in real GDP for the Eurozone (EZ), Sweden, Switzerland, the UK, and the US from the inception of the common monetary union.

We see that the Eurozone nations as a whole (and the membership changed slightly during this period given that not all 17 current EMU nations entered at the outset) have performed below all but Switzerland in the period before the crisis but have had the worst recovery since the crisis (even though the crisis was not as harsh from peak to trough).

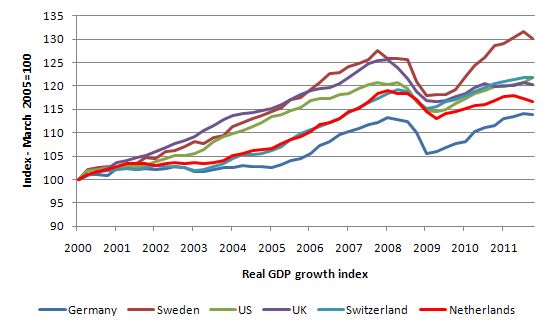

The second graph explicitly shows the comparison with Germany and the Netherlands, to overcome the fact that some stronger Eurozone nations (including some of the southern states during the credit-binge prior to the crisis) were blurring the picture.

The conclusion is even more emphatic.

The other point that Charles Dumas makes which is crucial when appraising the success or otherwise of the Eurozone is whether the growth performance of the powerhouse Northern nations, as modest as it was, reflected sound principles.

Charles Dumas writes:

Sweden and Switzerland grew as fast or faster in 2001-11 as they did in 1991-2001. The German and Dutch economies, by contrast, not only slowed down in 2001-2011 (to 1.25 percent from 3 percent in the case of the Netherlands), they also suppressed wage growth to adjust for the effects of the euro. As a result, real consumer-spending growth fell to a feeble one quarter of a percent a year in these countries. A recent report on the Netherlands’ experience in the euro calculated that if growth and consumer spending had followed the pattern of Sweden’s and Switzerland’s in the decade from 2001, Dutch consumers would have been 45 billion euros ($60 billion) a year better off.

In this blog – The German model is not workable for the Eurozone – I discussed this point in relation to the Hartz reforms that were imposed on the German workforce as a way to artificially tilt the EMU-playing field in favour of the Germans which had the effect of creating an unnatural economic environment for the Southern states to have to operate in.

The latter were doomed to fail no matter what independent of their fiscal positions (noting that Spain was running budget surpluses in the lead up to the crisis and Greece budget deficits).

We need to emphasise that the EU elites went one step further than the rest of the advanced world in adopting neo-liberalism. The decision to impose the monetary union meant they also abandoned floating exchange rates and deliberately, under pressure from the dominant Germans, chose to eschew the creation of a federal-level fiscal authority.

So we had the nonsensical situation of a common currency effectively rendering the member-states as foreign-currency users without an exchange rate and without the prospect of federal redistribution assistance in the face of asymmetrical and negative aggregate demand shocks. States such as California would have been bankrupt years ago if the US federal system had have adopted such a monetary system design. Same for states in Australia, for example.

The Germans had cultivated their own brand of extreme neo-liberalism which is known as ordoliberalism. The aim of the designers was to firmly limit the capacity of the “state”. I wrote about the influence of ordoliberalisms in this blog – Rescue packages and iron boots.

It was obvious that during the Maastricht process the neo-liberal leanings of the designers were never going to allow a fully-fledged federal fiscal capacity to be created, which would have allowed the EMU to actually effectively meet the challenges of the asymmetric aggregate demand shocks that the crisis generated.

Instead they wanted to limit the fiscal capacity of the state in the false belief that a self-regulating private market place would deliver the best outcomes and be resilient enough to withstand cyclical events. The Germans, of-course, knew that by signing up to the EMU they would have to change the way they pursued their mercantilist ambitions.

Previously, the Bundesbank had manipulated the Deutsch mark parity to ensure the German export sector remained very competitive. That is one of the reasons they became an export powerhouse. It is the same strategy that the Chinese are now following and being criticised for by the Europeans and others.

Once the Germans lost control of the exchange rate by signing up to the EMU they had to manipulate other “cost” variables to tilt the trade field in their favour. The Germans were aggressive in implementing their so-called “Hartz package of welfare reforms”. A few years ago we did a detailed study of the so-called Hartz reforms in the German labour market. One publicly available Working Paper is available describing some of that research.

The Hartz reforms were the exemplar of the neo-liberal approach to labour market deregulation. They were an integral part of the German government’s “Agenda 2010. They are a set of recommendations into the German labour market resulting from a 2002 commission, presided by and named after Peter Hartz, a key executive from German car manufacturer Volkswagen.

The recommendations were fully endorsed by the Schroeder government and introduced in four trenches: Hartz I to IV. The reforms of Hartz I to Hartz III, took place in January 2003-2004, while Hartz IV began in January 2005. The reforms represent extremely far reaching in terms of the labour market policy that had been stable for several decades.

The Hartz process was broadly inline with reforms that have been pursued in other industrialised countries, following the OECD’s job study in 1994; a focus on supply side measures and privatisation of public employment agencies to reduce unemployment. The underlying claim was that unemployment was a supply-side problem rather than a systemic failure of the economy to produce enough jobs.

The reforms accelerated the casualisation of the labour market (so-called mini/midi jobs) and there was a sharp fall in regular employment after the introduction of the Hartz reforms.

The German approach had overtones of the old canard of a federal system – “smokestack chasing”. One of the problems that federal systems can encounter is disparate regional development (in states or sub-state regions). A typical issue that arose as countries engaged in the strong growth period after World War 2 was the tax and other concession that states in various countries offered business firms in return for location.

There is a large literature which shows how this practice not only undermines the welfare of other regions in the federal system but also compromise the position of the state doing the “chasing”.

But in the context of the EMU, the way in which the Germans pursued the Hartz reforms not only meant that they were undermining the welfare of the other EMU nations but also droving the living standards of German workers down.

So it is clear that the German model that the “powerhouses” followed in the period leading up to the crisis attacked the welfare of their own populations and made it virtually impossible for the other member states to enjoy enduring success once they had surrendered their currency sovereignty and the capacity to adjust to trade imbalances via exchange rate variations.

It was obvious that with “fixed exchange rates” imposed on member nations, the there would be wide imbalances emerging in real exchange rates (measures of external competitiveness that take into account local productivity, price movements and nominal exchange rates) across the Eurozone.

It was obvious – and it was the German design – that nations such as Italy and Greece and the other nations that didn’t harshly repress the growth in living standards of their citizens – would become increasingly non-competitive. The “German Model” guaranteed that and the German growth was driven by that.

The fact that it was an unsustainable strategy appeared to escape the attention of the Euro elites, who to this day remain in denial.

Charles Dumas writes:

No wonder the Germans and Dutch are angry. But their anger should be directed at the governments that took them into the euro, not at the hapless citizens of Mediterranean Europe, who now are also suffering the effects of the common currency.

Sweden and Switzerland didn’t have to make any such sacrifice of ordinary people’s prosperity, while at the same time they enjoyed stronger employment as well as budget and current-account balances. That leads to only one conclusion: The euro was a mistake from the outset. It should be abandoned in unison and soon.

Whether we need to hold out Sweden and Switzerland as exemplars of sound fiscal practice is another matter. I would not. But the point is clear. The nations with flexible exchange rates and sovereign currencies have done better over the last 11 years (overall) and have come out of the crisis better, notwithstanding their own government’s attempts at undermining the growth process.

Charles Dumas also notes that the artificial sense of stability implied by the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) was “irrelevant to these problems, and in any case was ignored even by the policy’s main proponent: Germany”. He was referring to the “blithe assumption that such imbalances would be evened out by the ready mobility of labor” and itemised why such a neo-liberal belief was flawed from the start (“absence of a common language, tax structure and social-security entitlements etc).

In terms of the current stock take – “13 years later, where are we?” – Charles Dumas notes that fiscal austerity is pushing the financial ratios (deficits, public debt ratios) so revered by the Euro elites in the opposite direction to that desired – “The austerity program the Greeks are following — their only option, given that without control of their own currency they cannot devalue — has made both the deficit and debt ratios greater”.

The automatic stabilisers are swamping the discretionary net cuts given that the latter are severely undermining growth. This phenomenon is spreading across the EMU – with Italy having “no prospect of improvement” and “Other euro-area economies are in worse shape”.

As the recessive forces further undermine the financial viability of these nations – there will be a sequence of forced exits – “meaning that Portugal will probably have to leave the euro shortly after Greece”.

I am often asked about the nub of the European problem. My answer is always the same. The problem is the Euro. In saying that I am not denying that the lack of financial oversight as the ECB’s “one-level-fits-all” monetary policy created unsustainable real estate booms in certain nations, etc were not serious issues.

Further, there may be a need for some changes in tax systems (say in Greece) and other entitlements given the real outlook. But these issues are not causes. They are just conduits to amplify the crisis.

The major issue is the Euro.

Charles Dumas notes that:

All these symptoms of the euro’s poor design are linked. Wage suppression in Germany and the Netherlands has created artificial cost competitiveness, boosting exports to, and exacerbating inflation in, Mediterranean Europe. Lower wages in Northern Europe, meanwhile, have ensured weak demand for imports from the South. The resulting trade surpluses enjoyed by Germany and the Netherlands were, and will be, wastefully invested in such assets as U.S. subprime-mortgage paper and Greek government bonds.

In the future, the euro can survive only if these surpluses are given away as unrequited transfers — more or less what is happening now, in the form of bailouts. With 2012-13 prospects for global growth much weaker than in 2010-11, dependence on the German “export machine” will blight the whole European economy, heightening the malignant effects of the euro.

In other words, a fiscal transfer has to take place. In Australia, for example, fiscal transfers between states are mediated through the Commonwealth Grants Commission which works to ensure that standards of living are broadly similar across all states irrespective of economic performance.

But the reliance on Germany to generate the largesse which is then distributed to the nations that it has impoverished via the impoverishment of its own workforce (real wage suppression) is unsustainable.

The crisis has demonstrated that Germany is not capable of maintaining sufficient growth to play this role and could only achieve the modest growth it did by harsh suppression of the living standards of its own workers.

Charles Dumas correctly notes that the ECB is the only thing that is keeping the EMU afloat at present. I disagree with his assessment that the “ECB has engaged in unprecedented and dubious practices to expand the euro system’s central-bank balance sheet, accepting junk collateral against the provision of banking liquidity”.

The quality of the ECB’s balance sheet is irrelevant given that it is the sole issuer of the Euro. It can always fund anything in Euros!

But he is correct in saying that:

… liquidity provision will not stop fiscal tightening from deepening recessions in Mediterranean Europe, widening deficits and debt ratios, and threatening banking crises.

The long-term lending that the ECB has been engaged in to the commercial banks was based on spurious grounds – that lending to the private sector was being constrained by a lack of reserves. The reality is that credit growth is low in the EMU because the state of the private economies is so parlous that there is a paucity of credit-worthy borrowers actually seeking loans.

That is why these credit operations of the ECB will not stop a deepening recession. The path to growth has to come from fiscal expansion and austerity is deliberately preventing that from happening.

I also agree with him that “(s)equential disorderly exits from the euro need to be avoided because of the huge and extended financial turbulence they would cause”.

I have been advocating for years a break-up of the EMU. The crisis brought the design flaws into stark relief. You didn’t need to understand Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) to see that the system is inoperable and cannot deliver long-term prosperity. At best, its growth rates have been inferior and it biases nations towards constant recession or stagnancy.

Further, and most importantly, it is incapable of meeting large variations in aggregate demand that arise from time to time.

In that case, I agree with Charles Dumas who says an orderly break-up is essential:

… the simultaneous return to freely floating national currencies offers both the best economic outlook for the member states, and the least damaging euro-decommissioning process.

This would be challenging, of course, but it could be done. All domestic deposits, transactions and obligations (including home mortgages) would be converted 1-to-1 into each new home currency. The ECB would become the guardian of a legacy “European Transition Currency” into which cross-border euro contracts would be converted at the 1:1 ratio, but without money-creating powers … And leaving the euro area is likely to be cheaper than staying in it. A recent report on the Netherlands and the euro estimated the net initial cost to that country of leaving would be 51 billion euros, an amount the economy would more than recoup within two years, by not having to continue contributing to euro-area bailouts.

All of which I have been advocating for a long while now.

The point – also made by Charles Dumas – is that the real situation in many parts of Europe is now dire – Spain is heading for Depression-level unemployment levels (and they already have more than 50 per cent of their youth out of work). This trend is being mirrored right across Europe at varying intensities.

The current policy tack will make the situation worse.

Conclusion

As Dumas says:

The politics of Mediterranean Europe could soon be seriously destabilized. It is less than 40 years since the dictatorships of Franco in Spain, Salazar and Caetano in Portugal, and Papadopoulos in Greece ended. Their equivalents may not be about to return yet, but the risk of turmoil is increasing rapidly.

By hook or by crook, the situation will have to change. Orderly change will be preferred although I think the Euro elites will hang onto their mantra for a while yet as the situation crumbles further.

But advanced nations cannot endure 50 per cent youth unemployment rates for long periods. They cannot endure 25 per cent unemployment rates overall for long periods.

Governments cannot stand for election with any credibility while their policies increase suicide rates and impoverish increasing numbers of their citizens.

That is enough for today!

I would argue that the EURO in itself is not the only reason for the present problems. At least a similar if not more problematic aspect is the fact that cheap credit was provided to the south-european countries and this on the basis of money flows under the EU budget. However, any reasonable economist should have been able to recognise that the medium term sustainability for these countries with regard to their economic capacity to service such higher debt levels are at least questionable if not outright impossible. Therefore, the corresponding banking institutions should have restrained themselves of lending to this countries at the lower rates that became common after the EURO’s introduction. If interest would have maintained the risk premium as was common prior to the EURO, no such level of debt build-up would have been possible.

The present solutions try to (except part of the Greek debt) transfer the losses of mal-investments to the general public. To me, this is a violation of the principles of the free market at the very least but borders on theft as it affects property rights of the average person who was completely innocent in this scheme. The idea to separate risk from an investment does violate major principles which the success of Western society is based on and is an attack on the principles of the rule of law in the widest sense.

The rule of law intends to reward ethical and positive (for the country as a whole) behaviour and tries to punish incorrect and damaging behaviour. The present activities of governments and central banks do however promote exactly the opposite situation in that it rewards unreasonable risk taking by transferring eventual losses to the general public and punishes virtuous behaviour by paying interest below the level of inflation for real safe investments.

So, please, widen the topic a bit and you might find a lot of other aspects to the whole story.

Dear Bill

Denmark is another EU country that still has its own currency. Why wasn’t it part of the comparison?

Second, we should be comparing per capita GDP growth, not total GDP growth. The US still has a growing population while most European countries either have stable populations or populations that have very slow demographic growth. Total population isn’t a very good figure either. It is better to look at the population between 18 and 65. Maybe Germany has the same population as in 2000 but fewer people between the age of 18 and 65.

Regards. James

@Linus: “At least a similar if not more problematic aspect is the fact that cheap credit was provided to the south-european countries”.

I think this is just another symptom of the same Euro problem. As you note, by joining the Euro these countries received credit ratings commensurate with the whole Euro zone (erroneously low as it turns out, but that’s not the point) lowering the price of credit to levels inappropriate for those economies. Had they not joined, this would most likely not have occurred.

The real point is that in a sovereign state, the moral hazard you point out is a serious political problem, not a financial one. In the Euro zone they’ve turned this political problem into a financial one and used this to justify the “pump and dump” theft of wealth you refer to as “necessary”.

My 50 cents to the debate: http://economia.elpais.com/economia/2012/04/02/actualidad/1333358972_371777.html

The article says that 7 out of 10 new unemployed in February are from Spain. The outcome of the new austerity measures from the goverment. My bet is that by the end of 2012 Spain will have more 6 million persons unemployed.

moral hazard you point out is a serious political problem, not a financial one

Well, it becomes a political problem only if and when the misallocation of capital and the losses of malinvestments are not allowed to occur where they occurred, namely in this case due to lack of diligence and care by the investors when extending credit to those nations. However if we adhere to free market principles and to capitalistic rules, the problems will be with those investors who will have to take the losses.

It is not just simply a matter of moral hazard but represents a major breach of a rule based society; the results of these serious violations that are not simply occurring in Europe but in the USA too, are not yet known as of now. The idea that the USA has mastered the crisis is far from certain. I am waiting to see the consequences of these questionable actions that affect the whole fabric of society. Step by step it will lead to either an authoritarian, repressive state, if democratic rights can be eliminated or to chaos, if democracy (the electorate) is able to react.

The path between hyperinflation (loss of trust in a currency) and outright deflation becomes narrower by the day and within a few years we will find out on which side we dropped down.

Dear Bill:

I was delighted to see your brief mention of the role of the Commonwealth Grants Commission in managing equalization between Australian states (since your last week’s post “A seriously reckless act” I have being trying to work out the logic behind equalization). I wonder, when you have time, if you could discuss equalization in the context of MTT (or vice versa).

As in Australia (I would guess), equalization in Canada is an intensely political issue. Provinces are uninvolved in the transfer, except to the extent that they may qualify for cash payments; provincial governments do not contribute financially to equalization, and each province’s ability to raise tax revenues is unaffected by the transfer. Nonetheless, many Canadians believe that they are “making payments” to “have not” provinces, in a kind of inter-provincial charity scheme, via the federal treasury, as equalization is putatively “financed” from federal government “general revenues”. This misunderstanding is perpetuated, for instance, on Wikipedia, where it is (currently) written:

“As an example, a wealthy citizen in New Brunswick, a so-called “have not” province, pays more into equalization than a poorer citizen in Alberta, a so-called “have” province. However, because of Alberta’s greater population and wealth, the citizens of Alberta as a whole are net contributors to Equalization, while the citizens of New Brunswick are net receivers of Equalization payments.”

However (assuming I understand MMT correctly), since the Government of Canada is a sovereign issuer of currency, there are no actual “contributors” to our equalization system, nor does equalization have to be sourced from general revenues. So the Government of Canada is not robbing Pierre to pay Paul; it is just topping up Paul’s bank account to make sure he can access the same level of services as Pierre. So the whole equalization debate, in an MMT context, comes down to a simple calculation of how much Paul needs to be topped up. What recommendations would modern monetary theorists make for design of effective federal equalization systems?

Linus,

“The path between hyperinflation (loss of trust in a currency) and outright deflation becomes narrower by the day and within a few years we will find out on which side we dropped down.”

Loss of trust in a currency only becomes a problem where the issuer (the state) is unable to effectively collect taxes. Taxation creates a demand for the currency, provided the population have only a limited capacity to avoid or evade it.

Kind Regards

I don’t believe that an orderly retreat is a possibility. A disorderly retreat–at varying degrees of intensity and chaos–may well be in the offing. There are too many vested interests in the idea of the Euro. The Euro essentially represents the neoliberal programme of universal privatization and concentration of the commons in a few plutocratic hands; it is the movement towards universal corporate governance. I doubt they will give that vision up without a stiff fight.

Loss of trust in a currency only becomes a problem where the issuer (the state) is unable to effectively collect taxes.

And this can happen all too easily, especially in the developing world.

Well, that was a remarkably tendetious article.

First of all, what’s remarkable is that the author completely ignores the fact that Germany has had to deal with the consequences and costs of integrating a country (one larger than Greece in fact) into its economic structure – neither Switzerland nor Sweden nor the anglo-saxon countries have had an East Germany re-unification project to finance and shoulder, all by themselves. Certainly, such a project can have positive effects on GDP growth, like the short-lived 1990-1991 boom shows: generous pension and exchange rate regulations in the wake of the re-unification could artifically increase the purchasing power of the new citizens and increase consumption. But while the infrastructure investments kept having a positive effect on net GDP during the last decades, there were massive negative effects that quickly followed: deindustrialization and mass unemployment were long-lasting burdens on german economic growth from the mid-90s up until today even. Part of the reason why the labor market reforms were implemented was exactly the east german situation, and the slow economic growth periods Germany went through are due to far more than just introducing the Euro.

Also most fascinating, albeit truly inexplicable, is the permeating insistance that the german state in particular somehow tried to increase its wage competitivity only to spite and damage the southern state economies. How preposterous. Neither Greece nor Spain nor Portugal have shown any interest in wide-ranging economic reforms that would have been needed for them to compete with Germany in the fields that Germany cared about, and this has been the case long before the introduction of the Euro. Other up and coming countries – like Ireland – chose to specialize in areas that Germany didn’t directly compete in to the same extent. Yet others, namely Italy, while being a direct competitor to Germany, have also lacked a concerted effort to keep up, reform and produce growth in the 90s as well, before the Euro introduction. The competition was and still is not South Europe, but rather China, South Korea, India and (to a significantly smaller extent) the eastern european block – Germany has had to deal with the rapid rise of several major competitors in the industrial production field throughout the 90s and 00s with massive amounts of cheap labour becoming available on the global market. Cutting edge technologies are of course one way to keep ahead, but that only gives you a partial advantage – at some point you have to either level out your wage growth, or, alternatively, give up competing. Germany chose to not give up competing, and it was a choice that had pretty widespread support across the political field and in the unions. Naturally, one can argue that the balance on stagnating real wages has been tilted too far and many think that now is the time for a re-adjustment – hence the increase in labour protests and renegotiations of wages, as well as the critique of the mini-job sector and the lack of a universal minimum wage. I expect all this to be targeted by reforms within the next couple of years, if not by the current government, then by the next one. But it is pretty hard to argue with the fact that while the job creation in the last half a decade wasn’t perfect, and the quality of those jobs is debatable, and the statistics not quite as transparent and correctly presented as one wishes, Germany has still reached pretty solid ground in terms of employment, including enviable youth/young worker participation, and the positive trend has been pretty unwaivering throughout the crisis.

Also interesting how the article and Bill’s comments completely ignore the fact that financial transfers within the EU in general and the Eurozone in particular have been part and parcel of EU politics since forever. The common agricultural policy as well as the funds for regional development have been redistributing funds from net donor countries (like Germany) to net receiver countries (like Greece) through the EU budget for many decades now. Amazingly enough, a convergence of economic performance, regional development and standards of living has always been the main goal of the European Union project, including the Euro project.

In closing, it is also interesting to note that had Germany kept its sovereign currency, it would have had an instrument more, and not less, of manipulating the competitivness equation. Greece might have had more flexibility in masking their lack of competitivness through rampant inflation, but Germany could have used inflation as well, besides having the means of supressing wage growth if additionally needed. One only has to look at the abysmall growth performance of Greece in its drachma times throughout the 80s and the early-to-mid 90s to see that just having a sovereign currency does not mean that their economy would have competed any better with the german one, and some of the roots of their problems lie in things above and beyond the Euro.

@ Bruce

From the comments here I get the feeling that most here assume that the USA has successfully mastered the crisis and is now on the way to greener pastures. However, the FED and US Government have basically followed a very similar path to Europe with the major difference that they acted quickly and avoided the serious questions by kicking the can.

The same principles of free markets and capitalism have been violated in the most serious way by pumping liquidity into the system plagued by malinvestments and trying to avoid to make the required write-offs (banks still being allowed to value assets per model instead of market values). With their policies they try to give the banks time to heal. The required cleaning of the system as prescribed by Schumpeter (creative destruction) has been avoided by abandoning the principles of the free market and capitalism.

By now we are not yet in a position to evaluate the side effects of these actions but I dare to speculate some of the outcomes that will result.

1. The financial system will turn to be much more unstable as all that liquidity does not move in the areas the central planers at the FED hoped for but will create additional malinvestments with additional related problems down the road.

2. The purchasing power by the average citizen will be reduced step by step resulting in a maybe sudden or not so sudden reduction of consumption.

3. The rather off-handedly called moral hazard produces the need to turn the government to be more and more authoritarian or if democratic forces can assert themselves into a rather chaotic state.

On the level of cities and states we can recognise that the crisis has not been resolved by far and it is simply a matter of time until write-offs are unavoidable.

To assume that due the fact that a country can tax you in its currency does not negate the possibility that trust in a currency can be lost.

If one subscribes to the idea, that a room full of phds are able to manage the wellbeing of a country’s economy by manipulating monetary policies then I wonder, why the UDSSR collapsed. They were able to manipulate many aspects of economic activity to a much higher degree but failed nevertheless. To call the loss of the dollar’s value of 97% in 99 years a stable monetary policy, is a rather naive perspective in my eyes.

I am not all that certain of me being correct, but I did not find any reasonable arguments yet that changed my mind.

To assume that due the fact that a country can tax you in its currency does not negate the possibility that trust in a currency can be lost.

Correction:

The fact that a country can tax you in its currency does not negate the possibility that trust in a currency can be lost.

Austrian economics: 99.9% fact free.

@Linus Huber:

“The fact that a country can tax you in its currency does not negate the possibility that trust in a currency can be lost.”

It does. The fact that the state has a police force, army and court system that can put you in jail for not paying taxes means it doesn’t matter if you refuse to believe in a currency (whatever that means). In the end, you still need some of that money to avoid imprisonment, thus rendering trust a moot issue. The currency might be make-believe but those batons, guns and prison bars are not.

It does. The fact that the state has a police force, army and court system that can put you in jail for not paying taxes means it doesn’t matter if you refuse to believe in a currency (whatever that means).

That’s a nice theory, but, in practice, it doesn’t. The whole population can not be imprisoned.

@MamMoTh:

If you take things to that extreme, you’re basically talking about either a revolution or a total collapse of the state. I don’t think any monetary system or economic framework, even a neo-liberal one, can survive that. If the whole population refuses to pay taxes all at once, you need to consult a historian, not an economist.

Bill

Have you entered that competition to design the best way for a country to leave the eurozone?

A quarter of a million would keep you in surfboards and guitars for a few years.

@ Grigory

What else are these people presently in charge playing with. They do not care about the risk they take by their present policies with regard whether the situation may result in a total collapse but simply that things hold together while they still are in charge.

They always will state that things are working ok, not to worry. Well they do until they don’t.

“That’s a nice theory, but, in practice, it doesn’t. The whole population can not be imprisoned.”

The usual excluded middle argument.

Getting from here to there is a process over time not an instantaneous teleportation event.

Andrei,

“Also interesting how the article and Bill’s comments completely ignore the fact that financial transfers within the EU in general and the Eurozone in particular have been part and parcel of EU politics since forever.”

These transfers are generally seed funding that tries to leverage in private sector investment. They are however supply-side initiatives which don’t seem to work very well for economies that are demand deficient. Demand attracts private investment, so while economies are demand deficient supply-side initiatives will only be of limited use.

Fiscal transfers are needed to allow nations within the EZ to run higher budget deficits when there is a lack of demand.

Kind Regards

“Fiscal transfers are needed to allow nations within the EZ to run higher budget deficits when there is a lack of demand.”

That should read “Fiscal transfers are needed to allow nations within the EZ to spend more when there is a lack of demand”.

I don’t think I agree with that generalization – in fact, I would say that a majority of the structural funds are in fact targetted either at state investments or, as is the case of the current CAP, as direct payments to end-users.

The structural funds do have a self-involvment clause, but since they are largely used for infrastructure or environmental projects and research and education facilities they necessarily go through the regional state institutions that participate, and so that self-involvment is essentially government spending as well. Seen like that, the EU programmes are in fact a way to stimulate government spending in the member countries, since they promise funds that can only be accessed by contributing local funds as well.

Take for instance this PDF overview of various example regional development funds projects – excuse the glossy brochure format and the rah-rah tone of self-gratulation that exhudes from it, but it is actually a moderately interesting overview on the diversity of stuff the structural funds are financing. While there are of course plenty of example projects that involve private investors and companies, you will see that most of those are actually interface projects between R&D, universities and companies or pilot projects exploring some new technologies.

And the really big projects (in terms of total funding) are stuff like environmental reparations and infrastructure, which are of course state projects. I think that structural development in a port or a highway in Greece, or a light rail transit system in Irland or a rehabilitated rail line in Romania, or an upgraded airport in Bulgaria, are exactly the kind of state spending that one is talking about when advocating increasing the deficits in order to spur growth. And those are the projects where the majority of the structural EU funds end up.

Now there is a discussion to be had on exactly how many of these projects are actually well planned and bring added value, but that’s a discussion any form of government spending will be subject to – in fact, I think there is an argument to be made that EU-supervised funding like this will slightly increase the chances of a reasonably well planned project and slightly decrease the chances of corruption swallowing the funds.

Getting from here to there is a process over time not an instantaneous teleportation event.

The usual belief that black swans don’t exist.

Anyway, since the government can neither imprison a large part of the population for not paying taxes, nor force the private sector to net save in its unit of account, it is not true that the government can control the value of its currency solely through its coersive power.

@MamMoTh:

“Anyway, since the government can neither imprison a large part of the population for not paying taxes, nor force the private sector to net save in its unit of account, it is not true that the government can control the value of its currency solely through its coersive power.”

This is a denial of both history and current reality. Can a tyrant kill or torture everyone? No – and yet dictatorships are sustained by that very threat. Can everyone win the lottery? No – but millions buy tickets. People tend to think about themselves, not aggregates.

Can you even explain why people pay taxes now? Do you think it’s voluntary? If you went out into the street and asked people if they would choose to avoid taxes legally, what do you think their response would be? Of course they understand that not everyone can go to jail. But humans don’t have a hive mind – no one wants to be the first to be locked up. Yet if there was no enforcement of tax evasion punishment, watch how quickly everyone would join in if a few people started publicly getting away with it.

Could you give me an alternative explanation of why people pay their taxes right now, in this reality?

@ Grigory

To a great degree, most people feel that taxes are a reasonable way of ensuring that a government can ensure services to the population that are required to maintain an orderly and secure environment. To a great part, we do feel as well, that the government tries to implement and maintain rules that are favourable for the majority of the population. I would say that this is probably about the standard ideas in this regard.

Over the past many years, the supposed security provided by government led to a higher degree of individualism in that people are less and less dependant on each other. Individual difficulties are no more solved within a wider family unit but the government has taken over those tasks. These developments are resulting in increasingly antisocial behaviour by taking advantage of the government benefits while avoiding the related costs when the possibility exists. An average wage earner does of course not have the option to avoid taxes but when we look at those 1% of the population, we would certainly recognise that they find ways to avoid taxes by transferring wealth to greener pastures with lower or no tax obligations. Changes always start at the margin.

Let us consider an actual example. Enormous wealth has been transferred out of the country to avoid taxation. In today’s environment, the Government simply cannot control such flows of capital. A government might enforce a rule to disallow such transfers but by the time the law would take effect, we can be certain, that the capital has left already. Naturally, governments will chase those that cheat on taxes and will try to trace funds that disappeared for taxation but this is a rather hazardous job with very limited results as these tax-avoiders are watching every move by the government and are ready to react at a moment’s notice.

We increasingly live in a divided society with the 1% (or less) and their assistants (depending on the country 10 – 30% of the population) making the rules and ruling over the remaining the debt slaves that seem unable to rise above the immediate problems of daily life. The only difficulty for the 1% is to overcome real democracy that might threaten there position and I subscribe to the idea, that democracy will react in a most serious way.

To come back to the original point of loss of trust in a currency, I am still of the opinion that it might occur even in a developed country due to the very fact that capital is extremely easy to move nowadays. As however presently central banks the world over follow very similar policies (I think that this situation is coordinated by the FED) and increase their balance sheets dramatically, it is no more a question which currency is the most beautiful but rather which one is the least ugly.

Oh, the country I refer to is Greece of course, but Spain and others might not be far behind.

@Linus Huber:

“To a great degree, most people feel that taxes are a reasonable way of ensuring that a government can ensure services to the population that are required to maintain an orderly and secure environment”

Spot on – this is why we don’t have a revolt against taxes where we all dare the government to imprison everyone, MamMoTh style. There’s no simmering feeling of intense injustice.

I agree that our tax system is very skewed towards the 1%. However, demand for currency is a pull, and it can come from anywhere. If even a minority segment of the population has tax obligations in that currency, they create demand that spreads to everyone. If someone somewhere is willing to give up real resources for fiat money, then that creates an implicit convertibility between real and monetary resources. Think about people earning below the taxable threshold ($6000 here in Australia) – the money they have is still valuable because other people are willing to swap it for labor.

The fact that dollars might exist, untaxed and unaccounted for somewhere else in the world, does not change that fact. Capital may flee but the millions of people living within the borders of that country generally don’t. As long as they live there, and a sizable amount of them are asked to pay taxes in that currency, the currency will still be convertible to their labor, and thus will have value.

If you would like a ridiculous example of this, look no further than World of Warcraft. This online game has a totally fiat currency – it’s just gold that is useful inside the game and nowhere else. Yet people pay actual “real” money for WoW gold – it’s a 3 billion dollar industry. So why is there an exchange rate between completely fictitious money and ours? It’s because the game taxes you for playing (ie living in WoW-land) in it’s currency. You need gold to buy supplies and equipment needed to make gameplay easier. This creates a demand (in-game) for gold. But getting gold is time-consuming, requiring real-world labor. This sets up a conversion between gold and human labor, and human labor converts to real money. Note that not everyone needs to be taxed in gold for it to be valuable – a very small fraction of the population plays the game (I don’t). Yet the few that do get taxed in gold for playing are enough.

“The usual belief that black swans don’t exist.”

Even black swan events are a rapid continuous process, not a teleportation event.

And the solution is the same – dampen the change.

MamMoth:

That’s a nice theory, but, in practice, it doesn’t. The whole population can not be imprisoned.

It’s a nice theory that tax-driven, monetary economies don’t work, that actual universal imprisonment, rather than the universal threat of enforcement, and even more, the universal belief in the morality of money and debt, is needed. But that theory doesn’t work. Taxation, money, debt are incredibly effective means of directing human activity, and have frequently been used to enslave, imprison whole populations. That is what the IMF does. They have been amazingly successful in enforcing the odious debts they impose on their victims.

That taxes drive money is a tautology. It just says that the demand for money is driven by the demand for money, that debts you owe lead you to accumulate debts owed to you. MMT is the part of economics which is a fully developed, i.e. entirely trivial, scientific, mathematical, philosophical theory. Everything is an obvious corollary of trivial definitions. The fiat money, the taxes, the debts of a monetary system are far realer, of far more intrinsic value, than the silly stuff like gold and silver and even paper and electrons people have used to represent them, and laughably confused with them. (Meant to support Roger Erickson when he was making such a point here some time ago.)

Linus: If these dollars exist outside the country, unaccounted for and untaxed, then they just function as a tax, as long as they stay outside the country. They help drive the demand for dollars, not dampen it. The US government should just print enough dollars to functionally-finance counter the deflationary effect of this foreign dollar saving, the saving which itself has reduced the domestic ability to create the wealth that these dollars are (pen)ultimately a claim on. The only time they will then have real, major, possibly negative effect on the domestic economy is when they go back into it, during a time of full employment, from foreign suitcases and Treasury holdings. And then the gov has another shot at nabbing the crooks.

Here’s a short movie script, @Linus also:

Black Swan v. Tax System:

Black Swan: Awwwkk. I am the great & terrible black swan. Swan-Ra. Look upon my financial crises and despair! I will rend the value of your money with my talons of hyperinflation & financial crisis!

(Gunshot)

(Cooking Sounds)

Tax System: MMmm, that was good eating. Now my bro, Government spending, will pay the cook and tip the waiter for the nice meal. Hard to find such tasty swans these days.

The End.

Those who believe that the power of a government is unlimited, sounds extremely naive to me.

The most productive of society and the wealthy will leave a country that abandons the principles of Free Markets and Property rights and those staying behind will face an ever increasing poverty (loss of purchasing power). Money as well as people are able to migrate when a government’s policies become overbearing and destructive. Smart and wealthy people will always be welcome in other places. Everything, even government’s power, has its limits. The same will happen to the present bail out mania (and the transfer of losses to the general public) that rages in Europe and the USA, it will also end with much more serious consequences than when the Free Market would have been allowed to function.

“Smart and wealthy people will always be welcome in other places. ”

They will, but few actually move in reality. I’ve used that argument in court against the UK government and the statistical evidence is pretty clear. Most people, even the smart and wealthy ones, prefer to stay at home where their family and friends are.

“Everything, even government’s power, has its limits. ”

Nobody believes a government’s power is unlimited. But it does have the power to bring everything available into production which is to the benefit of all. Even the smart and the wealthy.

Well, we did not experience yet a major dislocation, but simply looking at Greece will show us how the population reacts to a dictatorial government presently in charge. Watching Greece will certainly provide some clues on how populations will react during distress and the idea that our own country is isolated from such a situation, may be a serious error. As far as I can recognise, masses of young people are leaving the country to find employment somewhere else (at least the educated ones) and enormous wealth has been transferred out of the Greek banks.