It's Wednesday and I discuss a number of topics today. First, the 'million simulations' that…

Rising working poor proportions indicates a failed state

The Sydney Morning Herald’s economics editor Ross Gittins wrote an article today (June 20, 2012) – This is no Sunday school: prosperity comes with pain – where he argued that the real world is not like his Sunday School (where all was forgiven) and that “discord and suffering are the price we pay for getting richer”. He might have also qualified that statement by saying that some get richer while others endure discord and suffering. I thought about that because I have been reading a number of related reports on the concept of the working poor – workers who for various reasons (pay, hours of work, job stability) live below the poverty line. I usually focus on the pain that unemployment brings but the working poor, many of whom are full-time workers, are also a highly disadvantaged cohort. It is not enough to just create growth that creates full employment. The policy framework also has to take responsibility for making sure that no-one who works is in poverty. A rising proportion of workers classified as working poor indicates according to metrics I use a failed state. The US is one such state.

For international readers, the Australian economy is currently undergoing a major shift in industry composition, employment structures and regional locations of activity that are causing huge pain to some sectors of the economy and the people that work in those sectors. I have written before about how Australia has a ‘two-speed economy’ at present although that dichotomy is contested and vaguely defined even for those, such as me, who seek to emphasise spatial growth differentials.

It is clear that there is increasing precariousness in the East coast economy (particularly, NSW and Victoria) where the majority of Australians live and where most of the employment is generated, relative to the prosperousness of the mining regions of Western Australia, Queensland and the Northern Territory.

Several coincident factors are driving the spatial growth differentials including strong terms of trade for non-rural, particularly base metal commodities and the consequential exchange rate appreciation. The former has flooded the mining sector with demand while the latter has damaged sectors such as manufacturing.

Further, the major city property booms have now abated and many households are now holding record debt levels while house prices fall. This is particularly so in Melbourne and Sydney where the industry dynamics are least favourable.

To cap that off, the Federal Government is now engaged in its obsessive pursuit of budget surpluses and squeezing the disposable incomes of the same households that are trying to deleverage.

On top of those trends are wider movements such as the digital revolution that has changed the way we shop and interact. In the last few days our two major newspaper companies (Fairfax and News Ltd) have announced huge changes in the way they do business with substantial job losses in traditional media and the likelihood that our major national printed dailies will disappear in the not too distant future being replaced solely by pay-for-view digital editions.

Gittins is commenting within this context and argues that:

Sometimes people are laid off because the economy is in recession, but at present it’s happening because powerful forces are changing the industrial structure of the economy. Older industries are shrinking; newer ones are expanding.

His point is that while it is “tempting to look for someone to blame” when one is a victim of structural change, “when there are major changes in the forces bearing down on an industry, there’s no point imagining change could have been resisted, nor any way all human pain could have been avoided”.

The message he wants to give us is that:

The economy isn’t run like a Sunday school. In an economy like ours, everyone – bosses, workers, customers – pursues their self-interest. The economic game is played for keeps. So everyone runs a greater or lesser risk of losing their job. Even bosses get the bullet.

Sure enough although one might conjecture that the amount of religious doctrine spun about the economy by the dominant neo-liberals (aka ideology) is not far removed from the sort of religious fantasy (aka nonsense) that young children have to put up with in “sunday school”.

Further, the playing field in which the “bosses, workers, customers” pursue their self-interest is hardly level – those categories blur the underlying class differences that still pervade our basic interactions in a capitalist economy.

I know – talking about class is so yesterday and it makes me a dinosaur – someone with a sclerotic mind that hasn’t caught up with the new age of household shareholders and youthful entrepreneurship and all the rest of the cant that the neo-liberals use as smokescreens to obfuscate what lies beneath the heap of lies they spin.

Class is alive and functioning. Bosses representing capital still control the means of production (although in more complex ways than before) and workers are still workers without the means to live without working. The bosses (as representatives of capital) still want the workers to work as hard as they can and to pay them as little as they can get away with.

The workers want to, in general, work as little as they can and get paid as much as they can squeeze out of the system. The two objectives remain in conflict with each other. We can put whatever veneer we like over all of that but when push comes to shove the conflict emerges – redolent of the industrial beginnings and intense.

And it still remains that the bosses are one and the workers are many and that mass unemployment tips the scales further in favour of the former.

I agreed with much of the rest of the article about shifting economic power (the rise of India and China) and technological advances and how they do not by necessity lead to mass unemployment. They certainly change the composition of employment and as that process occurs there are winners and losers.

I gave a talk on Monday night at a National Conservation Council Public Forum on Clean Energy where I discussed the employment prospects in renewables and what the closure of the coal industry would mean. I noted that progressives needed to accompany their zeal for renewable technologies (the discussion tends to get lost in the gee-whiz characteristics of bio-mass and community energy – it all sounds good) with a recognition that the transition to these new technologies had to be managed in a just way – we have written a series of papers/reports on the concept of Just Transition.

The point is that mass unemployment is not the only thing government policy should seek to alleviate. It also should be designed to minimise the costs of structural change by giving appropriate guarantees of income security and training to those who are the losers. I see a Job Guarantee as being part of that policy framework.

Anyway, Ross Gittins promotes the hands-off approach (that is, the neo-liberal approach) to structural change – that is, the losers will get picked up in the groundswell of change if they are resilient enough and absorbed in to new jobs elsewhere. The lessons of history are that such a market-mediated processes are very imperfect and tend to leave regions, demographic cohorts etc out in the cold for a long period, especially when the macroeconomic settings are wrong – that is, mass unemployment and underemployment is tolerated by the fiscal authorities.

The latter situation prevails today in Australia. There are 12.6 per cent of willing workers officially idle (unemployment or underemployed). Remember that to be classified as “employed” one only has to work one hour or more in the Survey week. So the process of structural change that is going on in Australia (and everywhere) at the moment is much more painful and costly that would otherwise be the case if the Government ensured there were enough jobs to go around.

Ross Gittins finishes by saying:

Market economies deliver almost continuously rising material prosperity. But they do so by continually changing, and that change comes with a fair bit of pain for many people.

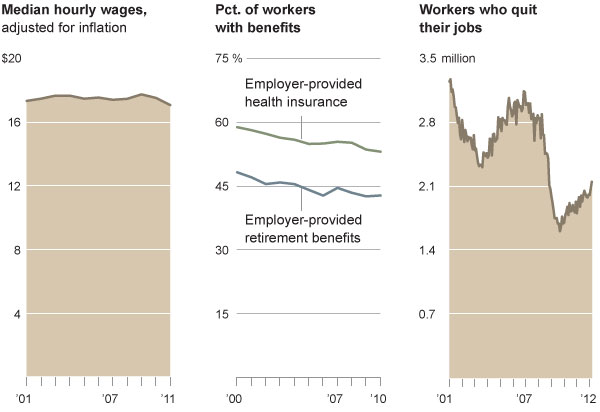

There was an interesting graphic in the New York Times (June 19, 2012) under the title – Tough Times, Even for Those With Jobs – which I reproduce here. It originally appeared in the The State of Working America, published by the Economic Policy Institute.

There was a related article in the New York Times (June 18, 2012) – Lost in Recession, Toll on Underemployed and Underpaid.

The New York Times article focuses not on the “misery” of unemployment but on the fact that “many middle-class and working-class people who are fortunate enough to have work are struggling as well”.

We must always consider broad measures of labour underutilisation when considering the state of the economy, because underemployment is now a serious problem across many nations and creates a phenomenon that is referred to as the Working Poor.

So when a commentator like Ross Gittins talks about prosperity from growth he ignores the rise of the Working Poor in recent decades.

The New York Times article says:

These are anxious days for American workers. Many … are underemployed. Others find pay that is simply not keeping up with their expenses: adjusted for inflation, the median hourly wage was lower in 2011 than it was a decade earlier … Good benefits are harder to come by, and people are staying longer in jobs that they want to leave, afraid that they will not be able to find something better. Only 2.1 million people quit their jobs in March, down from the 2.9 million people who quit in December 2007, the first month of the recession.

The graphic above bears testimony to these claims.

The observation about quits is very important.

Economics students who undertake a mainstream approach are taught that fluctuations in unemployment reflect supply-side changes arising from imperfect information (about wages and inflation) and/or changing preferences of workers between leisure and work.

In this mainstream macroeconomics labour market model, the real wage (the purchasing power of the money wage) is assumed to be determined in the labour market at the intersection of the labour demand function and the labour supply function. The equilibrium employment level is constructed as full employment because it suggests that every firm who wants to employ at that real wage can find workers who are willing to work and every worker who is willing to work at that real wage can find an employer willing to employ them. Frictional unemployment is easily derived from the Classical labour market representation, as is voluntary unemployment.

Please read my blog – Less income, less work, less income, more work! – for an introduction to the “classical” labour market.

Holding technology constant (and hence the labour demand function is fixed), all changes in employment (and hence unemployment) are driven by labour supply shifts. There have been many articles written by key mainstream economists (such as Milton Friedman) that argue that business cycles are driven by labour supply shifts.

The essence of all these supply shift stories is that quits are constructed as being counter-cyclical despite all evidence to the contrary. This induced Lester Thurow in his marvellous book from 1983 – Dangerous Currents to ask:

why do quits rise in booms and fall in recessions? If recessions are due to informational mistakes, quits should rise in recessions and fall in booms, just the reverse of what happens in the real world.

So one of the most simple ways to reject the mainstream macroeconomics conception of the labour market, which constructs unemployment as being a supply side phenomenon and hence quits as being countercyclical is to look at the quit rate.

As the New York Times article (reporting the State of Working America) reports (and the graphic shows) the quit rate has fallen sharply in the US during the downturn.

In fact, if you examine any data on quit rate behaviour from any country (that you can get data for) you will sese that the quit rate behaves in a cyclical fashion as we would expect – that is, it rises when times are good and falls when times are bad. Many studies have demonstrated this phenomenon for several countries where decent data is available.

It is one of those simple but terminal flaws that pervade the neo-classical economics approach. Too often the debunking exercising focuses on arcane and very technical arguments that are lost in the ether (for example, the Cambridge Controversies). But one doesn’t have to get involved at that level to realise how defective the mainstream approach is – it gets the most simple and obvious facts wrong.

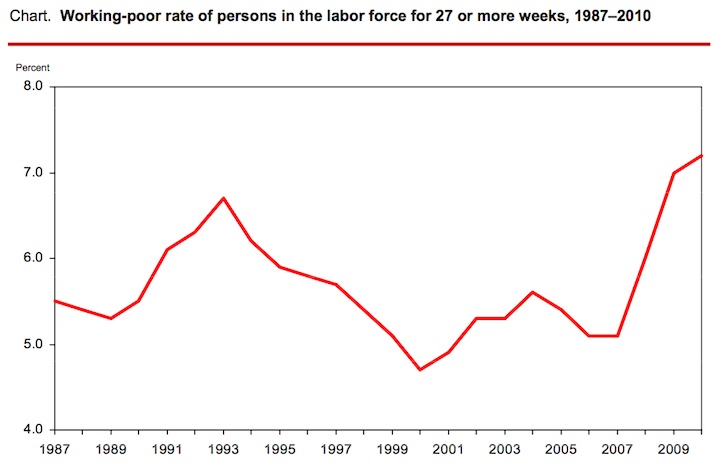

Lets go back a little in time a . The US Bureau of Labor Statistics publishes an annual A Profile of the Working Poor and in the 1999 Edition (BLS Report 947) we read that:

In 1999, 32.3 million people, or 11.8 percent of the population, lived at or below the official poverty level-2.2 million fewer than in 1998. While most of these people were children and adults who did not participate in the labor force, some 6.8 million were classified as the “working poor.” This was 362,000 fewer than in 1998, continuing a 6-year downtrend. The working poor are individuals who spent at least 27 weeks in the labor force (working or looking for work), but whose incomes fell below the official poverty level. Of all persons who worked 27 weeks or more, 5.1 percent were classified among the working poor in 1999, down 0.3 percentage point from the previous year.

So 5.1 per cent of those who worked in 1999 were impoverished, which, in itself, is an indictment of policy failure in the richest economy in the World.

Of the working poor cohort, the following breakdown provides some further insight:

Below Poverty Line (%)

Total in labor force – 6.5%

Did not work during the year – 37.5%

Worked during the year – 6.2%

Usual full-time workers – 4.8%

Usual part-time workers – 11.7%

Involuntary part-time workers – 23.2%

Voluntary part-timers – 10.1%

So you can see that being out of the labour force was the major reason for poverty in the US in 1999 and that unemployment was the next major cause of poverty (although one might argue that the causality is bi-directional a problem that proposals like the Job Guarantee would overcome).

Low pay explains why 4.8 per cent of full-time workers were below the poverty line in 1999. 11.7 per cent of part-time workers were also poor in 1999, reflecting a combination of a lack of hours, usually accompanied by low pay and unstable job tenure.

The BLS Report allows the reader to further drill down into gender, ethnicity, industry and occupation, marital status and family structure. All the cross tabs provide further insights.

The A Profile of the Working Poor, 2007 showed that the percentage of working poor rose after the 2001 recession but fell again as growth ensued. By 2007 there were:

… 7.5 million were among the “working poor.” This level is slightly higher than the level reported in 2006 … In 2007, the working poor rate-the ratio of the working poor to all individuals in the labor force for at least 27 weeks-was 5.1 percent, unchanged from the rate reported in 2006 … 3.6 percent of those usually employed full time were classified as working poor, compared with 11.9 percent of part-time workers.

That is, some improvement especially among full-time workers.

Fast track to now. The most recent report – A Profile of the Working Poor, 2010 (BLS Report 1035), published in March 2012 showed a considerably worse situation:

… 10.5 million individuals were among the “working poor” in 2010; this measure was little changed from 2009 … In 2010, the working-poor rate-the ratio of the working poor to all individuals in the labor force for at least 27 weeks-was 7.2 percent, also little different from the previous year’s figure (7.0 percent) … 4.2 percent of those usually employed full time were classified as working poor, compared with 15.1 percent of part-time workers.

The following chart provides a better historical view of the way in which the American economy has fared in this context. It is taken from the BLS chart in the 2010 Profile.

You can see that, in fact, 1999 was a good year and 2010 is the worst year shown here (spanning 1987-2010). Unemployment is also at the highest level over the same period.

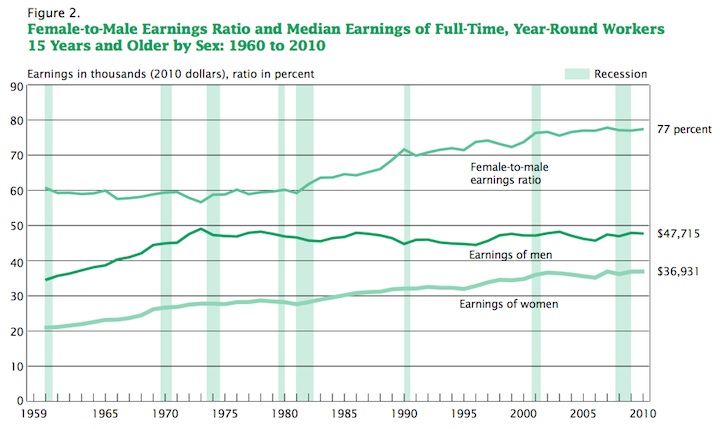

In September 2011, the US Census Bureau published – Income, Poverty, and

Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2010 – which contained further interesting evidence of the deterioration in the US economy.

The following graph (their Chart 2) covers real median earnings for men and women since 1959 in the US for full-time, year-round workers who are persons “who worked 35 or more hours per week (full time) and 50 or more weeks during the previous calendar year (year round)”.

I found this a stunning graphic. Real male full-time median earnings have been constant since the early 1970s in the US.

So not only is the US economy failing to produce enough jobs and hours of work but for those who are lucky to have work the real median pay is not growing.

The New York Times article also notes that:

And household wealth is dropping. The Federal Reserve reported last week that the economic crisis left the median American family in 2010 with no more wealth than in the early 1990s, wiping away two decades of gains. With stocks too risky for many small investors and savings accounts paying little interest, building up a nest egg is a challenge even for those who can afford to sock away some of their money.

While the American narrative (and I don’t really want to get into cultural or national stereotyping here) tell the world how great the land of the free is the objective data tells a story of a failing economy with a dysfunctional policy framework.

As the introductory graphic shows:

1. Workers are receiving less employer-provided retirement and health benefits with no commensurate expansion from public equivalents.

2. Real median pay is stagnant of falling.

3. Workers are hanging onto these low quality jobs because they are better than no job and the prospects for career expansion via job mobility are extremely low.

Conclusion

When I give public presentations on poverty and unemployment, I am often asked in the question time how I judge policy effectiveness. I reply with a simple rule of thumb.

I judge the policy framework and the economy by not how rich it makes society in general but how rich it makes the poor!

It is not an original benchmark but I think it is an effective one. It doesn’t make much sense to speed up the train if you leave an increasing proportion of the potential passengers behind on the station.

A society that generates rising poverty rates and cannot even see that all those working are over the poverty line is a deeply flawed one.

The neo-liberal legacy is clearly leading to failed states. The US is one such state in my view based on things that matter.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2012 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

That last figure for median income is very hard hitting. It blows a smoking hole in any pretensions by mainstream economists that we should accept extreme inequality because of all the “progress” made under neoliberal reforms. Unfortunately I’m sure all the Austrians will claim that real median incomes haven’t risen because the fed inflated away all the gains, and what we really need is even more neoliberalism and an end to fractional reserve banking.

The bosses (as representatives of capital) still want the workers to work as hard as they can and to pay them as little as they can get away with.

The workers want to, in general, work as little as they can and get paid as much as they can squeeze out of the system. The two objectives remain in conflict with each other. Bill Mitchell

What if workers were paid with common stock? Then wouldn’t the distinction between capital and labor lessen? And why isn’t labor paid with common stock? Because there is no need to so long as the banking cartel allows the capitalists to steal their workers’ purchasing power?

I can’t see much prospect for improvement in the Australian situation as long as our two major political parties are enamoured of the neo-liberal abomination. PM Gillard has the gall to go galivanting overseas and lecturing all and sundry how they should follow the economic management example of Australia.It would be funny if it was not so pathetic.

Re Clean Energy – The National Conservation Council,along with most other environmental groups,has not got a clue on this issue as they continue to believe in the fairy tale that renewables (aka unreliables) will displace fossil fuels – in their dreams and the fossil fuel industry loves them for it.

The only clean energy source which is practical and acheivable in the time frame needed is nuclear energy.

@Podargus:

We already have a free, massive fusion reactor:

http://landartgenerator.org/blagi/archives/127

As for unreliability:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/High-voltage_direct_current

A HVDC line could go from Perth to Sydney and only have 12% transmission loss, or go halfway around the world and lose 60% in transmission. The sun is shining somewhere all the time.