I have received several E-mails over the last few weeks that suggest that the economics…

Revisionism is rife and ignorance is being elevated to higher levels

Sometimes I read things and consider either I live in a parallel universe or the writers do. I always conclude the latter. There is an increasing number of articles and commentaries coming out which aim to re-write history in favour of the writer’s reputation or that of his/her mates. Revisionism, which includes the practice of personal reincarnation is rife at present. Everybody seemed to predict the crisis. Even those that clearly in their own writing didn’t have a clue that the trouble was coming predicted it. As part of this process, key organisations that should be learning from the crisis such as the BIS are demonstrating that they are in an educational void. They have become just another propaganda machine. And so the crisis continues as ignorance is elevated to higher levels.

Which tradition?

Take for example this UK Guardian article written by on J. Bradford Delong (June 29, 2012) – Explaining current US Treasury rates is beyond even the economic prophets – which caused a bit of a stir among progressive economists over the weekend after it was released. He is an American economist.

Guardian readers would have understood from this article that there is a strong group of leading (mostly US) economists including Dr Delong himself who knew all along the crisis was coming and what should be done about it when it came because they were all working in a tradition of Hyman Minsky, despite at least one admitting he only recently read any of Minsky’s work.

The paragraph that inflamed many was:

So the big lesson is simple: trust those who work in the tradition of Walter Bagehot, Hyman Minsky, and Charles Kindleberger. That means trusting economists like Paul Krugman, Paul Romer, Gary Gorton, Carmen Reinhart, Ken Rogoff, Raghuram Rajan, Larry Summers, Barry Eichengreen, Olivier Blanchard, and their peers. Just as they got the recent past right, so they are the ones most likely to get the distribution of possible futures right.

I won’t go into detail about the contributions of this coterie. But we know full well that characters like Larry Summers (part of the Committee to save the World – Please read my blog – Fiscal austerity damages real growth and prolongs the financial downturn – for more discussion on this point) was a key player in the financial deregulation that led to the bust.

We know that Olivier Blanchard failed to understand the macroeconomic implications of the financial deregulation. Please read my blog – We are sorry – for more discussion on this point.

In a 2010, IMF Staff Position Note entitled – Rethinking Macroeconomic Policy, written by Blanchard with co-authors Giovanni Dell’Ariccia and Paolo Mauro we read that:

… we thought of monetary policy as having one target, inflation, and one instrument, the policy rate. So long as inflation was stable, the output gap was likely to be small and stable and monetary policy did its job. We thought of fiscal policy as playing a secondary role, with political constraints sharply limiting its de facto usefulness. And we thought of financial regulation as mostly outside the macroeconomic policy framework … [and] … Little attention was paid, however, to the rest of the financial system from a macro standpoint.

They also indicated they believed in the money multiplier and the myth that reserve volumes influence lending (“This led to an emphasis on the “credit channel,” where monetary policy also affects the economy through the quantity of reserves and, in turn, bank credit.”) which is expounded in detail by Blanchard in his macroeconomics textbook.

In other words, he didn’t understand how the modern banking system actually works. Please see my blog – Money multiplier and other myths – for more discussion.

He believed in Ricardian Equivalence – one of the myths used to justify fiscal austerity. The IMF paper he co-authored said they had “wide skepticism about the effects of fiscal policy, itself largely based on Ricardian equivalence arguments.” Please read my blog – Deficits should be cut in a recession. Not! – for more discussion on Ricardian equivalence.

Blanchard and Co wrote that they considered that monetary policy alone “could maintain a stable output gap … [so] … there was little reason to use another instrument” (that is, fiscal policy). And then along came the crisis that Delong claims they all predicted, which has demonstrated that monetary policy has failed dramatically to rekindle growth.

Blanchard and Co said that they had:

Increased confidence that a coherent macro framework had been achieved was surely reinforced by the “Great moderation,” the steady decline in the variability of output and of inflation over the period in most advanced economies.

Please read the blog – The Great Moderation – where I show why this proposition was never well-established.

Dr Delong himself hasn’t actually drowned himself in glory in the recent period. In a Bloomberg opinion piece (July 5, 2011) – Sorrow and Pity of Another Liquidity Trap – J. Bradford Delong – asserted:

… (t)here is only one real law of economics: the law of supply and demand. If the quantity supplied goes up, the price goes down”

He was then confounded by the apparent abrogation of that law when it comes to US Treasury bond yields. He notes that between 2002 and 2007 the increased supply of bonds led him to conclude that:

this expanded supply would exert substantial pressure on interest rates to rise.

But he rationalises this by arguing that the “demand for Treasuries was inordinately high, in part because the supply of alternatives was low” and suggests that private bond issuers reduced their demand for funds because they lacked “confidence” in the set of available investment opportunities.

He admits to thinking that it was only a matter of time before “the market’s appetite for Treasury bonds at high prices and low interest rates had to reach its limit” given that “(s)upply and demand isn’t just a good idea – it’s the law”.

He also says that in 2008 he considered the US “had a little time for expansionary fiscal policy to boost the economy … before the bond-market vigilantes would arrive” and:

They would demand higher interest rates on Treasury bonds, which would begin seriously crowding out the benefits of fiscal stimulus. The U.S. government would have to react, pivoting from fighting joblessness, via deficit spending, to reassuring the bond market via long-run tax increases and spending cuts to Medicare and Medicaid.

That is all straightforward mainstream macroeconomics – the crowding out story and the view that private bond markets essentially call the shots and the government is a passive player in seeking funds.

The empirical world certainly didn’t pan out as he claimed and it is clear that bond markets will buy whatever debt is being issued at high prices (low yields).

There is also no inflation threat emerging from the expansion of the central bank balance sheets – quite the opposite.

He then offered his mea culpa:

Although I worked for three years in the Clinton Treasury Department, and am a card-carrying member of the economist guild, I predicted none of this. Like most of my peers, I was wrong. Yet the most interesting thing is that I could have – should have – been right. I had read economist John Hicks; I just didn’t quite believe him.

The reference to J.R. Hicks was in relation to the concept of a liquidity trap. I considered that link more fully in this blog – Whether there is a liquidity trap or not is irrelevant and more recently in this blog – The on-going crisis has nothing to do with a supposed liquidity trap.

Like Paul Krugman, who is included in Dr Delong’s group of cogniscenti, Dr Delong was “wrong”, because in his own words, he didn’t consider the liquidity trap to be a serious description of real possibilities despite being having sat in his “first graduate economics class in 1980? listening “to Marty Feldstein and Olivier Blanchard – two of the smartest humans I am ever likely to see” who assured him that “Hicks’s liquidity trap was a very special case, into which the economy was unlikely to wedge itself again”.

Hmm. Dr Delong represented the Hicks liquidity trap (from the 1930s) in terms of “that interest rates paid by creditworthy governments would remain low after a financial crisis … even in the face of enormous budget deficits that greatly expand the supply of government bonds”.

Delong claims that normally when interest rates fall (and bond prices rise) business investment is stimulated and household saving becomes less attractive – both stimulatory outcomes. But during a financial crisis, there is “an increased desire among businesses and households to safeguard more of their wealth in cash” and total spending falls and a recession emerges.

What if the central bank conducts open market operations (with the fancy title of quantitative easing) and buys “bonds for cash”? He says that:

… when rates become so low that there’s little difference between cash and short-term government bonds, open-market operations cease having an effect; they simply swap one zero- yielding government asset for another, with their hunger to hold more safe, liquid assets unsatisfied. This is the liquidity trap.

So he concludes that “we need deficit spending” to fill the gap left by private spending. But even though the government runs a deficit and borrows “creating more of the safe, cashlike assets that private investors want” why is the demand for bonds so high? He doesn’t answer that. In a true liquidity trap (a la Keynes) the demand for bonds evaporates because people fear capital losses.

For someone who in his own words is an economist “who … [is] … steeped in economic and financial history” this is a major oversight.

Dr Delong prefers to channel his version of Hicks and conclude that “(a)s long as output remains depressed and there is slack in the economy, printing more bonds will have negligible effect in increasing interest rates” and says he is “sorry” for ignoring that message.

The point is that De Long “generally” believes deficits to be damaging for private spending because he thinks they drive up interest rates but in this special case – they are safe … for a time. Eventually the build-up in the monetary base will be inflationary in his view because supply will exceed demand. The current demand for “cash” will move into a demand for goods and services and all those reserves will be loaned out and spent.

Please read the following blogs – Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary – for further discussion as to why increasing banks reserves neither enhance the capacity of the private banks to lend or increase the risk of inflation.

I needn’t say too much about Drs Rogoff and Reinhardt. Why haven’t they sought to correct on the public record the continued mis-use of the analysis that appears in their book This Time is Different. A lot of commentators quote this book without it seems having read it in detail.

Of critical importance, quite apart from the other issues that one might have with Reinhart and Rogoff’s analysis (and I have many), one has to appreciate what they are talking about. Most of the commentators do not spell out the definitions of a sovereign default used in the book. In this way they deliberately (or through ignorance – one or the other) blur the terminology and start claiming or leaving the reader to assume that the analysis applies to all governments everywhere.

It does not. On Page 2 of the draft, Reinhart and Rogoff say:

We begin by discussing sovereign default on external debt (i.e., a government default on its own external debt or private sector debts that were publicly guaranteed.)

Their analysis, inasmuch as it has any credibility relates to problems that national governments face when they borrow in a foreign currency. Please read my blog – Watch out for spam! – for more discussion on this point.

But why haven’t the authors written strongly about this abuse of their research?

I could go into massive detail about the work of all the above-named “economists who are steeped in economic and financial history” and in Dr Delong’s estimate were right!

You will be hard-pressed to find anything in their work (Raghuram Rajan and to some extend Barry Eichengreen apart) that would suggest they were predicting the crisis and understood why it occurred and how it can be solved.

The thing that curled the ears of many progressives was the claim that these economists worked in the Minskian tradition. The best response to the article was from my colleague Randy Wray – Brad Delong: We’re all Minskians now!. Randy was a doctoral student under Minsky.

That was a very outlandish piece of reinvention by Dr Delong, consistent with many economists who are now attempting to play catch-up and blur what they did or didn’t know or believe pre- and post-crisis.

Some of the outrage against Dr Delong was driven by personal ego (I am not including Randy in that assessment) and in that sense was unhelpful. Sort of along the lines – “why wasn’t I included in the list of economists who are steeped in economic and financial history who knew all?”.

But substantively, it is a real concern when economists who basically operate within the mainstream macroeconomics tradition lay claim to prescience and channel writers that they have never written about or whose thoughts they have never advanced – except now – when it is obvious to them that they were wrong.

You should read Randy’s reply to Dr Delong for more detail on some of the other claims he made in the Guardian piece.

And then … the BIS Annual Report

The Bank of International Settlements – 82nd Annual Report – covering the period from April 1, 2011 to March 31, 2012 (released June 24, 2012) is an exemplorary demonstration of how the World’s key financial and economic institutions have failed to learn anything from the crisis and persist in perpetuating erroneous analysis.

But it goes beyond that even. If extended to its logical conclusion it is hard not to conclude that the BIS (and central banks in general) feel they are blameless in the creation of the crisis and further, despite their regular calls that they are independent, think that their policy ambit includes treasury, industry and labour market policy.

The degree of their self-belief is only matched by the level of their revisionism and ignorance.

I haven’t the time (nor the inclination to review the whole document) but here are some snippetts.

In Chapter I. Breaking the vicious cycles the problem according to the BIS is laid out. We read that the high levels of debt carried by the private sector as a result of the “leverage-driven real estate boom” has spawned a “necessary deleveraging process for households” which is “far from complete”.

We can agree on that. But then the BIS claim that an:

… important factor slowing the deleveraging process among households is the simultaneous need for balance sheet repair and deleveraging in the financial and government sectors.

Why conflate the private and government sectors? No reason is given. Apparently, it is just a given that governments have to cut their debt at the same time as the non-government sector is doing so. Earlier they talk about the problem of reliance on export-led growth.

Astute readers will realise that under current institutional (voluntary) arrangements which are in place in most nations and determine the way in which governments spend (and issue debt), it is impossible for the government and non-government sectors to simultaneously reduce debt. One sector’s surplus is the other sector’s deficit.

The reason that the private deleveraging process is struggling is because governments are acting in violation of that “sectoral” rule and, by imposing fiscal austerity, are killing growth – the source of private saving.

Who understands that? Certainly not the writer’s of the BIS Annual Report.

We then read that the:

… given the ongoing need to improve balance sheets, any effects from stimulative fiscal policy will be limited by overindebted agents using additional income to repay debt rather than spend more. As a result, weak growth is likely to continue.

Which tells us two things:

1. Government deficits stimulate income which is then the source of private saving (as above). The private debt overhang is so large as a result of the neo-liberal endorsed credit binge that there is a need for higher than normal saving ratios to fix the private balance sheets.

2. Government deficits are thus too small as evidenced by the weak growth. From a sectoral perspective, aggregate spending can come from the government sector and/or the non-government sector. If the latter are engaged in a period of weak spending then growth requires an enhanced contribution from the government sector. It is impossible to engender income and output growth any other way.

But the BIS thinks that the real cause of the weak (and in some cases non-existent recovery) is that:

Persistent imbalances across industries are also impeding recovery. Because labour and capital do not easily shift across industries, the misallocation of resources during the boom tends to work against recovery in the aftermath of a crisis. Hence, countries where the sectoral imbalances were most apparent are facing higher and more protracted unemployment as their industrial structure only slowly adjusts.

This is the standard neo-liberal structural (supply-side) explanation. The reality is that demand collapses in some sectors more dramatically than others. Unemployment in those industries rises. But the collapse is a demand-driven outcome.

Sudden recessions such as the current crisis do not occur because of industry imbalances. They occur because demand collapses. It is clear that demand patterns can create unstable industry structures – such as the massive growth of construction in Spain servicing the real estate boom.

But the solution isn’t to wait for the industry structure to resolve itself.

The free market economists are continually claiming that economies have to go through blood-letting if there are structural imbalances so that the high-cost industries are expunged and resources re-allocated back to the best-use patterns.

This argument never adds up the costs of letting the “market work”. As I have indicated before doyens of the market such as Milton Friedman has acknowledged that his estimate of such a resolution might be something like 15 years – that is, 3/4 of one generation confined to unemployment and the rest of the nation enduring massive, permanent income losses.

Further, it was the belief in the self-regulating private market which led to the massive deregulation and lack of regulative oversight of the financial sector. The resource misallocation they talk about occurred because of a lack of regulation – because the market was allowed to do its own thing more than in the past.

So why will the resource allocation improve without major government intervention?

The other point, in relation to the costs of adjustment, is that the role of the government sector should be to attenuate those costs. It can do that very easily in a major downturn by increasing its role as a direct employer.

If the non-government sector fails to employ then there is only one sector left.

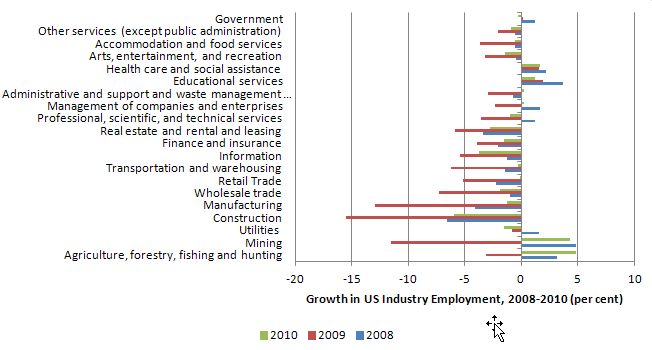

Just to check where the employment was lost in the US between 2008 and 2010 I dug out the US Bureau of Labour Statistics data – Industry Output and Employment and compiled the following graph.

We should recall that the US housing bubble burst in 2006 but growth continued across the industry structure until overall demand started to falter in 2008.

It is clear that negative growth in 2008 and 2009 was spread broadly across the industry structure but was worse in Mining, Construction, Manufacturing, Wholesale trade, Retail Trade, Information and Real Estate.

That is a pattern common in most recessions – whether they be financially motivated (risky balance sheets) or driven by pessimistic investment.

Moreover, the response of government in employment terms has been pathetic and goes a long way to explain why unemployment rose so dramatically in the US and has stayed at those persistently high levels for some years now.

The same lack of public sector response is common in other nations.

If you believed the BIS, then there is nothing that policy can do. Monetary policy has done everything and is now too expansionist and fiscal policy is dangerous given the alleged sovereign debt problem.

There was another extraordinary argument presented in the BIS Annual Report. Under a sub-heading “Overburdened central banks face risks” we read that:

The extraordinary persistence of loose monetary policy is largely the result of insufficient action by governments in addressing structural problems. Simply put: central banks are being cornered into prolonging monetary stimulus as governments drag their feet and adjustment is delayed.

First, since when does a central bank in a sovereign nation face any default risk? What does being overburdened mean in the context of a currency issuer? Nothing!

Second, the reason why the “loose monetary policy” (and we could dispute that assessment given that it is likely required real interest rates are lower than they currently are in most economies) is being maintained is because central bankers have generally expressed concern about the weak growth outlook. Also, given their obsession with inflation-first strategies, the subdued inflation environment is giving no signal for rate rises.

The reason their is weak growth has everything to do with an over-indebted private sector being confronted by governments imposing fiscal austerity onto them. Growth has to falter in those circumstances.

Further, since when has the central bank or the central bank of the central bank become commentators on fiscal policy. They are unaccountable, unelected and claim to be independent.

But under the sub-heading “The abysmal fiscal outlook” we get the full montie. This is the most appalling section (Chapter V) of the Report. Here is a sample:

… the fiscal maelstrom has toppled many sovereigns from their unique perch where the market considered them to be essentially free of credit risk and, in that sense, riskless. The loss is particularly worrisome given weak economic conditions and a global banking system still largely dependent on government support. The shrinking supply of safe assets is harming the functioning of financial markets and driving up funding costs for the private sector. And it is helping push banks into risky practices, such as rehypothecation – that is, the use of the same collateral for multiple obligations. Over the past year, much of the world has focused on Europe, where sovereign debt crises have been erupting at an alarming rate. But, as recently underscored by credit downgrades of the United States and Japan and rating agency warnings on the United Kingdom, underlying long-term fiscal imbalances extend far beyond the euro area.

So why are yields low in the US, UK, Australia, Japan? Why are they high in Spain and Greece? Why do they insist on referring to the Eurozone countries as sovereigns?

You will note that the assessment of fiscal sustainability is solely based on what the rating agencies thinks. That should tell you everything. The rating agencies downgraded Japan in the early part of this century and yields didn’t move. They downgraded the US recently and yields fell.

Why not just consider the reality – yields are low where governments issue their own currency and variously higher where they don’t.

The BIS say:

Sovereigns under fiscal pressure have been losing their risk-free status – and the accompanying economic benefits – at an alarming rate.

Which sovereigns? The Euro nations, where yields have risen, indicating bond markets have assessed that the relevant member states are at risk of default (and have defaulted in the case of Greece) do not issue their own currency and do not have their own central bank. The bond markets know that. They have not attacked any nation with its own central bank because they know in those case there is no solvency risk.

The rest of the BIS analysis in this context is spurious to say the least.

Conclusion

Revisionism, which includes the practice of personal reincarnation is rife at present. Everybody seemed to predict the crisis. Even those that clearly in their own writing didn’t have a clue that the trouble was coming.

And those organisations that should be learning from the crisis such as the BIS are demonstrating that they are in an educational void. They have become just another propaganda machines.

And so the crisis continues.

Its lucky the Tour de France is on – otherwise one might get a bit depressed.

The way things are done in Romania

When pesky watchdogs get in the road – the solution is simple. This snippet came from the EU Observer.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2012 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Have the MMT people lobbied the Guardian for a right to reply to this propaganda?

If one accepts that the yields on bonds of states that didn’t alienate their right to issue currency are low for reasons other than supply and demand, then one must admit that “a state is not one more economic player as any other”.

The chain of inferences coming from admitting that “a state is not one more economic player as any other” results in admissions not very palatable to MSE: it is propping up minority interests at the expense of majority interests.

The issue threatens the cornerstone of the whole propaganda scheme.

On the other hand, truth is slowly beginning to emerge. Therefore: let’s revise.

Why do you falsely claim that Olivier Blanchard has ever believed in Ricardian equivalence? Why do you falsely claim that the statement “Fiscal austerity damages real growth and prolongs the financial downturn” is a criticism of rather than an agreement with Larry Summers?

There is an awful lot here that just ain’t so…

Brad,

Why do you go Fox News on everyone that critiques you rather than responding in any substantive way? I have seen nothing from you in any of your comments on any of these pieces that amounts to anything more than shooting the messenger and/or moving the goal posts.

You wrote the piece suggesting all these people got it right, and it has been countered with links that this is not so. You wrote the piece suggesting these people were Minskyans when those of us who know Minsky’s work know that there is little or nothing in their work resembling Minsky. Further, those truly working in the Minskyan tradition did get things right well before 2007 and also got right many of the things you admitted to not getting right in 2008; you curiously make no mention of any of this. For a piece that was intended to praise those that got it right and also point out those who got it right were working in the Minskyan tradition, this seems more than a little strange.

Will you respond in a way befitting an academic at a top university or should we expect more of the same?

Best,

Scott Fullwiler

I think there are 2 different issues here.

Larry Summers played a negative policy role in the Clinton administration via his support for disastrous banking deregulation.

On the other hand it is quite true that as a new keynesian he has supported fiscal deficits to remedy the current recession.

Of course, he supports deficits based on different theoretical gounds than MMT – liquidity trap, etc. – but still he is on the same side of MMTers in the present, crucial political debates over austerity.

Summers, Krugman, Delong et alia are tactical allies. IMO they should be supported whenever they come out against austerity while keeping clear that MMT has a different overall approach to economics, inherited from the post-keynesian school – that is to say, empirically more valid and theoretically more sound.

DeLong was a Clinton appointee and he takes great pride in being part of the government surplus generated during the latter part of that Administration.

Now that he has seen the Minskian light, I wonder if he realizes that those surpluses were the flip side of the run up in private debt, in which case he can also take credit for our current situation.

I wonder if DeLong chose a UK newspaper in which to publish his revisionism because the UK is nowhere near as alive to the failure of ‘great moderation’ economics. Nor has the UK the vibrant culture of economic debate that in the US has publicised, debated, created and collaborated in promoting alternatives to this failure.

I can well understand why the likes of that ugly sister of the IMF Blanchard, wants to off-shore the rehabilitation of his reputation, but surprised if DeLong expects anything other than a hoot from critics of neo-conservative economics. But we’re in an era of ‘anything goes’ as far as the PR lies and deceptions fallen stars in politics and economics will promote about themselves. After all, we’re on the way to GFC2.

The problem with a lot of these prominent US neoclassical or neoconservative economists is exactly that. They are prominent. Proximity to power in the (now only temporarily) most powerful country in the world has given them a false and vastly inflated sense of their own insightfulness, astuteness and brilliance. Within the distorting force field of US capitalist politics, ideological orthodoxy and not historical or analytical accuracy is the key to political, professional and social success. Access to mainstream media for the purposes of promulgating views and agendas is given only to those who toe the line and support the ideological status quo.

Power is not about morality or honesty nor is it about scientific or historical accuracy. Power is about those in power being right even when they wrong. What is happening with these orthodox and prominent economists is exactly this. They are displaying the consistent behaviour of those in positions of prominence and power. They are right even when they are wrong.

I applaud and support the efforts of modern heterodox economists like Bill Mitchell and Steve Keen who are attempting to steer economics in an empirical direction. Sadly however, I think they will not be successful. The instrumental power of the plutocrats and their orthodox, neoclassical legitimation system is now far too great. They (the powers that be) will never allow late stage capitalism to be reformed. However, since capitalism is an endless growth system and since it is now running up against the hard limits to growth it will destroy itself, the carrying capacity of the biosphere (for humans) and even the holocene climate benignity. Beliefs that we humans are special, exist over and above nature and have an “endless progress” destiny are unempirical and philosophically immature. As the ancient Greek philosophers understood, hubris is the precursor of tragedy.

Dear Brad DeLong (at 2012/07/02 at 22:03)

Thanks for your comment.

One can only judge a viewpoint by what is written and heard. The IMF Staff Position Note I quoted from – entitled – Rethinking Macroeconomic Policy, which was written by Olivier Blanchard with co-authors Giovanni Dell’Ariccia and Paolo Mauro, begins as such:

There was no attempt to separate the authors’ views from the collective we. It is apparent that they are talking about their own journey and that of the profession.

Further, Blanchard et al., write:

Then under the sub-heading “A Limited Role for Fiscal Policy” we read:

So, fiscal policy was ignored because of RE arguments.

As noted the authors give the impression they are undertaking a self-assessment as part of the mainstream macroeconomics profession and trying to work out why they were so wrong.

I do not believe that I have deliberately manipulated any quotations to “fit” the person to a stereotype. If they really thought these ideas were nonsense from the outset why would they not qualify the collective (we) as appropriate to allow the reader to appreciate that these were not their personal views. The overwhelming impression from the paper is that they were being good enough to admit they were wrong and to tell us what they had learned from the errors made.

In the textbook by Olivier Blanchard – Macroeconomics (1997 edition – the only one close to hand), the author consider Ricardian Equivalence in Section 29.2 (pages 597-600).

We read:

He then notes that “tax cuts rarely come with the announcement of tax increases a year later. Consumers have to guess when and how taxes will eventually be increased. This fact does not by itself invalidate the Ricardian equivalence argument. No matter when taxes will be increased the government budget constraint still implies that the present value of future tax increases must always be equal to the decrease in taxes today.”

So from an inter-temporal perspective, Olivier Blanchard is telling his students that today’s government deficits have to be repaid by future generations. Students would conclude that future budget surpluses are required to repay these current deficits. Those spurious notions – an feature of long-run New Keynesian models form a fundamental part of the Ricardian equivalence notion.

It is true that he then indicates that the short-run empirics do not seem to support the short-run version of Ricardian Equivalence (perhaps as he suggests consumers know future taxes might rise but suspend the distant event from their immediate decision-making).

From that he concludes:

The policy recommendation is that the government has to run surpluses to offset the deficits. It is unclear from that piece text as to whether the thinks the lower long-run output more than offsets the short-run gains.

The way in which he sees higher government debt lowering investment is via a combination of mainstream crowding out effects and expectational effects. The latter are the sort of effects that feed into Ricardian Equivalence notions.

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) rejects the basic New Keynesian long-run proposition relating to deficits as outlined above.

As to Larry Summers, his role in the deregulation of the financial system as part of the Clinton Administration is well known. It is clear that he (and all those named by you in the Guardian article) consider fiscal policy to be useful at present, which separates your group from the Barro-Chicago camp. But that doesn’t mean you are part of the Minskyian tradition. It puts you in the more traditional deficit dove camp.

best wishes

bill

A social-democratic, progressive and broadly Keynesian economist who is prominent on the Australian blog scene stated in his blog a strong preference for “Hard Keynesianism”. He explicitly stated this meant that government deficits (in downturns) and government surpluses (in booms) should balance out over the business cycle. He initally made this point without any qualification that I couild see. I pointed out that this meant (in a growing economy) that the money supply would shrink in proportionate terms over time and deleteriously affect the financial economy’s capacity to generate aggregate demand. He then added the qualification that “balanced over the business cycle” contained the implicit assumption that the money supply would be allowed to expand (via a controlled net deficit) to meet the money supply needs of economic growth.

I believe he wrote in complete good faith and did indeed mean this from the outset. My concern at that point in the debate was about the tendency of many economists to “talk in code” with one message for the cognoscenti on the one hand and another message for political rhetorical purposes on the other. Put another way, this means that many economists entering the public political debate do not speak literally, precisely and comprehensively with all necessary caveats on each statement. Amongst most qualified economists “balanced over the business cycle” no doubt does contain the implication that money supply be permitted to expand to meet growth. However, it took my literalist pedantry and committment to reason “reductio ad adsurdum” to draw this fact out.

The average man in the street, a layperson in economic matters, will take the statement “balanced over the business cycle” quite literally. Conservative or orthodox political rhetoric also promotes this view that literally balancing the government budget over time is an iron clad rule. Then, when more progressive economists say “balanced over the business cycle” but mean in fact “balanced over the business cycle but with a deficit allowance to expand the money supply in line with growth” they are;

(1) remaining subservient to the dominant political-rhetorical lie about government deficits and what they mean in complex practice; and

(2) failing to educate the public properly so that the democratic polity can reject simplistic falsehoods about national economic policy.

Whilst saying this in the context of growth capitalism, I do not resile from my statements above that economic growth is about to hit the hard limits to growth. The challenge for MMT is to not be another theory that is fighting the last “war” (the war for adequate structural deficits and full employment in a growth economy) when it should be preparing us to fight the next “war” (organising an economy in a de-growth scenario).

It is patently clear from limits to growth analysis and ecological footprint analysis that we have reached the limits to growth (about 2010, plus or minus 5 years) and are now in overshoot mode. In overshoot mode we can continue expanding for some time while we use up irreplaceable, non-renewable resources; our natural capital in other words. At some point, a collapse to well below our current level of population and production then becomes inevitable. Whilst it is fashionable for many of those who admit limits to physical growth to still say that there are no (or very distant) limits to knowledge growth, qualitative technology growth and artistic/aesthetic/humane growth the actual case is considerably more sombre.

Even growth in these above more qualitiative arenas is physically mediated (inevitably) by growth in infrastructure complexity and energy use. The laws of thermodynamics indicate that knowledge growth and technology growth, being higher states of order, require higher levels of energy “consumption”, or more accurately exergy consumption, to produce and maintain.

MMT needs to engage with thermoeconomics or biophysical economics in order to develop a comprehensive economic discipline to face our real, impending situation and the dire existential threat it poses.

I think you set the bar a little high, ikonoklast. To demand that economists set out and organise how life should be lived in toto is , in my opinion, ridiculous.

However, To ask them to explain their positions and prognoses is not.

If professor mitchell’s efforts to illuminate the catastrophic tendencies of his peers disappoint you, you should seek out something that satisfies your desires, not demand their immediate satisfaction from someone outside that line of work.

Mitchell,Wray, Hudson all go back to the funny old idea

“What do we do with the people?”

and their answer seems to be:

Value them, for they will not be there forever,at the end you might be alone

@Ikonoclast

“MMT needs to engage with thermoeconomics or biophysical economics in order to develop a comprehensive economic discipline to face our real, impending situation and the dire existential threat it poses.”

I agree. But this does not mean going for de-growth.

The P2P Foundation blog published recently a, imo, very good critique of degrowth:

http://blog.p2pfoundation.net/essay-of-the-day-five-argumentative-fallacies-and-one-methodological-fallacy-without-which-degrowth-cannot-stand/2012/06/30

The immediate problem we face is not lack of energy or other resources. The immediate problem we face is lack of employment or productive occupation.

Actually, the problem is more difficult. Given the increase in productivity up to the present and foreseeable in the next future, the problem we face is not a problem of having people working productively; it is a problem of having people sanely occupied.

GDP growth can continue with lowering energy intake per GDP unit. Say that global GDP could triple while only doubling the energy intake. Would that be sustainable?

The answer is fundamentally we do not know. There is too much uncertainty. Under current technology and known resources, it would not be. But what if we discover both new techniques (and new sources) to harvest energy and refresh the planet?

It is also not clear that higher order states require more exergy. A human requires less exergy than an elephant.

Economists and politicians could quite contribute to a sustainable future by learning and practicing MMT 😉

That would give engineers the proper environment to address the issues of potential energy lack or global warming. Example: cutting energy consumption by half while letting living standards unchanged in the developed countries is a realistic aim.

“”MMT needs to engage with thermoeconomics or biophysical economics in order to develop a comprehensive economic discipline to face our real, impending situation and the dire existential threat it poses.””

For goodness sake, economics can barely hold onto its own prejudices, let alone these neo sinecures ‘byophisicality/thermoconics’

In my human opinion,mmt shoud keep its original fococus on full employment and zero humiliation

Bill: Excellent deconstruction. While it is true that the New Keynesians are on-board for some more fiscal stimulus their analytical framework is faulty. Moving forward, if they are willing to read and use Minsky, I welcome them aboard. But to really understand Minsky they must throw out the entire macroeconomic framework they learned, they’ve used, and they teach. All the textbooks must be thrown out. They must disown virtually everything they’ve ever written. Personally I don’t care if they do a public Mea Culpa. They can do it privately and then move on. But I see no reason for them to try to declare they had it right all along and to try to defend the indefensible.

Critics of my 2 previous posts have variously said;

1. “I think you set the bar a little high, ikonoklast. To demand that economists set out and organise how life should be lived in toto is , in my opinion, ridiculous.”

Yes, it would be ridiculous if I had said “that economists set out and organise how life should be lived in toto”, but I didn’t say that. I said that MMT theorists need to engange with thermoeconomics or biophysical economics in order to develop a comprehensive economic discipline to face the de-growth challenges which will inevitably follow from overshooting the hard limits to growth.

2. PG questions the de-growth prediction and states “The immediate problem we face is not lack of energy or other resources. The immediate problem we face is lack of employment or productive occupation.”

In fact both of these are problems right now. Energy and other resource shortages are beggining to impinge in the Middle East and North Africa and elsewhere. The BRICs and the West will soon be competing for energy and other scarce resources. In other words if energy etc. is not in immediate shortage in the West it soon will be within as little as 5 to 10 years, well within necessary planning timeframes.

PG further says, “Say that global GDP could triple while only doubling the energy intake. Would that be sustainable?” The answer would be no unless we can transition to a point where renewables supply all of the this energy and extra energy i.e. double the quantity of energy useage.

And states: “It is also not clear that higher order states require more exergy.” Actually it is 100% clear from the Laws of Thermodynamics no exceptions to which have been found in the known universe.