It's Wednesday and I discuss a number of topics today. First, the 'million simulations' that…

Growth is lagging because spending is lagging – the solution is clear

A recurring theme in the press and one that I get several E-mails about a month is that a national government has “more space to net spend” if its past history of deficits and debt are lower than otherwise. This is also related to the acceptance by many so-called progressive economists that national government budgets should be balanced over the course of the business cycle – that is, it is fine to go into deficit when there is a downturn but the government should pay it back via surpluses when the economy is strong. Neither proposition has merit but serve as powerful buttresses for the continuation of the neo-liberal attack on government fiscal freedom and full employment. Government deficits have not caused the crisis. Growth is lagging because spending is lagging. If the non-government sector cannot sustain aggregate spending to ensure unemployment drops then there is only one sector left in town folks!

These myths were once again rehearsed in the Washington Post article by Robert J. Samuelson (unrelated to the late economist Paul Samuelson) – Why U.S. economic policy is paralyzed – (July 9, 2012).

The Washington Post, caught in the thrall of Peter G. Peterson and his money, is intent on being a vehicle for neo-liberal propaganda. And this was a media organisation that exposed the Watergate scandal. Now while I assess the paper to be an ideological rag – I still conclude that it remains influential – which is more the pity.

Robert J. Samuelson basically claims that:

… the retreat from balanced budgets has weakened America’s response to today’s downturn, the worst since the Great Depression. It has limited government’s ability to “stimulate” the economy through higher spending or deeper tax cuts – or, at least, to have a meaningful debate over these proposals. The careless resort to deficits in the past has made them harder to use in the present, when the justification is stronger.

The weak US federal government response to the current downturn is due to the power of ideology over sound economic sense. Its less than robust fiscal response to the crisis has no financial basis – it is being driven by pressure that the conservatives are placing on the government to engage in fiscal austerity.

That pressure also has no grounding in reality. The underlying hypothesis adopted by the conservatives is that dramatic cuts in national government spending will not damage growth and will provide space for the private sector to expand.

Despite strong evidence to the contrary, the conservatives still hang onto the notion that government net spending undermines private enterprise – except, of-course, when it is in the form of direct handouts to the business sector. To be fair, the extremists even eschew corporate welfare.

There is no magical cut-off threshold where the government encounters an inability to “stimulate the economy”. A fiat currency-issuing government can always purchase whatever is on offer in the currency that it issues. That is not to say that it always should buy whatever is on offer. Quite clearly it needs to net spend enough such that the gap left by non-spending non-government entities (households, firms, external sector) is closed and income produced at full employment is continually spent.

Warren Mosler’s little piece in the Huffington Post today (July 9, 2012) – The Certainty of Debt and Taxes – The Fiscal Cliff Burden of Proof – is very succinct in this regard.

Where there are “desires to not spend” this means that “at full employment, either a private sector entity or the government will be spending more than its income to offset the demand leakages”. I would use the terminology non-government sector here instead of private sector to ensure exhaustion of the relevant categories but the point is clear.

Budget deficits are the norm for a nation that desires full employment and experiences a private domestic sector deficit that is smaller than the external deficit.

Robert J Samuelson attempted to clarify the previous statement:

The balanced-budget tradition was never completely rigid. During wars and deep economic downturns, budgets were allowed to sink into deficit. But in normal times, balance was the standard. Dueling political traditions led to this result … Kennedy’s economists, fashioning themselves as heirs to John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946), shattered this consensus. They contended that deficits weren’t immoral and could be manipulated to boost economic performance. This destroyed the intellectual and moral props for balanced budgets.

That would appear to be a revision of modern history. I would conclude that the history of the US since the 1930s has been marked by deficits in 85 per cent of the years – some goods real GDP growth years and some bad. That is, in some years (and sequence of years) the budget deficits have been driven by cyclical impacts, while in many other years, the discretionary budget deficits have driven growth (or allowed growth to recover).

It is always useful to consult the evidence. Budget data is available annually in some detail from 1930 from the US Government Budget Office.

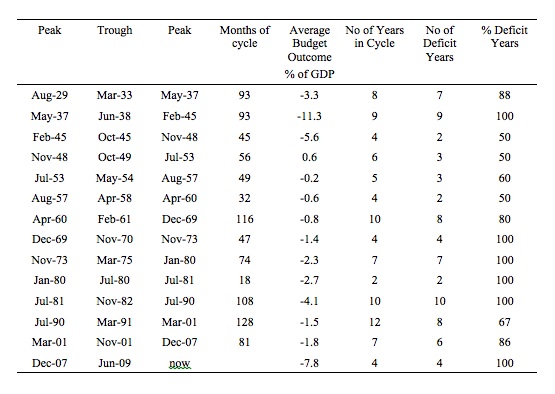

Using the US Business Cycle Expansions and Contractions analysis from the US National Bureau of Economic Research we can examine the budget balances “over the cycle” since 1930. The NBER dating shows that there were 14 distinct business cycles between August 1929 and June 2009 in the US.

The following Table shows the distinct business cycles since 1930 – Peak to Peak and the Average Budget Outcome over the full cycle. It also shows the proportion of years within each cycle that the budget was in deficit. Given the NBER analysis dates the cycles by quarters and the US Budget Office provides historical budget data for years, there is some approximation in fitting the years to the cycles. But a check of quarterly budget data since 1960 suggests that the approximation is not misleading in any way.

The point is that the only time the US federal budget achieved a average surplus over the business cycle was for the 1948-1953 cycle. The other point to note is that real GDP growth was negative in 1948 and 1950 as the government tried to run a pro-cyclical budget position.

It is also hard to mount a case that there was a balanced budget bias in the period prior to 1960s. It is clear in the immediate Post World War 2 period, the governments ran surplus more than in other periods.

I would note that there are no valid intellectual props for balanced budgets per se. The claim that budget deficits should be offset by budget surpluses over the business cycle is not only a defiance of history but also logic. Why should that be the case? They say it is to keep debt levels down to some level. Which level? Enter more mythology – but we will come back to that soon.

The moral prop is, in fact, not an ethical positional (I am aware of the debate about the differences that might be made between morals and ethics in moral philosophy) – but an ideological one. There is nothing intrinsically good about a budget balance. It is an accounting result driven by the behaviour of all sectors in the economy. The government cannot never guarantee a particular budget outcome is delivered such is the dependence on the final outcome on non-government spending and saving decisions (via their impact on economic activity and government revenues – the automatic stabilisers).

The ideological position is that government is best small and insignificant and the free market is best left unregulated. The prop that argues against budget deficits is just the same prop that claims that self-regulating private markets maximise income and wealth for all. I assume that as a result of the crisis – no-one with any basic analytical capacity – would believe that nonsense any more.

Remember that a budget deficit adds to aggregate demand (spending) because government spending (the injection of spending) exceeds taxation revenue (the drain or destruction of spending). Similarly, a budget surplus drains aggregate demand because the injection is less than the drain. Surpluses destroy private sector purchasing power and put a squeeze on private sector wealth.

So what happens to aggregate demand overall depends on what components are adding to spending and what components are draining it.

Consider the states where a nation can run a budget surplus without undermining overall aggregate demand. First, the external sector could be in surplus (so that foreigners overall are spending more in the local economy than the locals are spending abroad – which includes net income transfers across borders). So the external sector would be adding to aggregate demand overall.

What about the private domestic sector? If it spends less than it earns (that is, it is net saving as a sector) then it will be draining demand. This situation would normally occur if the leakage from household saving is greater than the injection from private sector investment (capital formation).

Can the government safely run a budget surplus in this case and still maintain high quality services and full employment? It all depends on whether the external net injection is greater than the net leakage from the private domestic sector. If so, then growth can continue and the government will be able to sustain a budget surplus. This is the situation that Norway, for example, finds itself in.

Clearly that combination of balances is rare and also not possible for all (or even many) nations.

If the private domestic sector spends more than it earns – so dis-saves as an overall sector – then it would be adding to aggregate demand. Given it is budget constrained, the private domestic sector could only achieve this outcome if the external sector was in deficit and the “foreign saving” was funding the private domestic sector deficits.

Under these conditions as long as the credit-driven private domestic spending boom outweighs the leakages arising from the external deficit, the economy will grow and the government would be able to record budget surpluses on the back of the GDP growth (boosting tax revenue). This is the outcome recorded in many nations leading up to the crisis.

But of the two situations, this possibility is unsustainable because eventually the private sector balance sheet becomes precarious. Once the private sector begins the process of balance sheet consolidation, then the budget surpluses quickly vanish and what happens to the economy depends on the response of the political classes to the need for higher budget deficits.

A private credit-binge cannot sustain growth indefinitely. So when people advocate balanced-budgets averaged over the business cycle they are also advocating that the private domestic balance should be the average external balance over the same cycle. If the external balance is in deficit on average (as it is in most nations) then this advocacy amounts to desiring the private domestic sector to be continuously increasing its debt. The combination that created the crisis we are in.

When neo-liberals and their ilk make these sweeping statements – that balanced budgets are moral – they never reveal that they understand the macroeconomic linkages that tie the budget outcome to the other balances.

As an aside, I have received several E-mails recently asking me about sectoral balances. Who invented them etc? There is a notion out in the cyber world that Wynn Godley invented them while he was at Cambridge and the Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) proponents mis-use Wynn’s work. That might be the topic of another blog but for now be assured that while Wynn Godley certainly raised awareness of the sectoral linkages in the recent era, this framework is derived directly from the National Accounting framework and has been around for a while before Wynn Godley wrote about them. They were in macroeconomics books in the 1960s.

According to Robert J. Samuelson, the “all these permissive deficits” as morality collapsed in the US (from Kennedy onwards) are now coming home to roost are to blame for the current lack of recovery:

The recovery is lackluster. Economic growth creeps along at 2 percent annually or less. Unemployment has exceeded 8 percent for 41 months. But economic policy seems ineffective. Since late 2008, the Federal Reserve has kept interest rates low. And budget deficits are enormous, about $5.5 trillion since 2008.

It is very simple – the recovery is lacklustre because the deficits have been too small. The fact that the near zero interest rate regime has not filled the gap (stimulated aggregate demand) should also inform us about the ineffectiveness of monetary policy. And … it has nothing to do with being in a so-called liquidity trap.

Please read my blog – The on-going crisis has nothing to do with a supposed liquidity trap – for more discussion on this point.

Economic growth is a response to aggregate spending. We know that inflation is falling. So we can safely conclude there is insufficient nominal aggregate demand growth at present.

GDP after all can be decomposed into the value element (market prices) and the real component (output). GDP can grow just because there is inflation. But its lacklustre performance is all down to a lack of real output growth. More spending is needed.

Robert J. Samuelson is opposed to more spending because:

… it collides with the 1960s’ legacy. Running routine deficits meant that the federal debt (all past annual deficits) was already high before the crisis: 41 percent of the economy, or gross domestic product (GDP), in 2008. Huge deficits have now raised that to about 70 percent of GDP; Krugman-like proposals would increase debt further. It would approach the 90 percent of GDP that economists Kenneth Rogoff of Harvard and Carmen Reinhart of the Peterson Institute have found is associated with higher interest rates and slower economic growth.

Ahh – I know you were waiting for the RR work to rear its ugly head. Journalists typically bring it into play when they want to refute the more spending approach.

The US government cannot spend more – so the argument goes – because it will push the debt level beyond the so-called 90 per cent of GDP danger line and so growth will be destroyed.

I wonder how many of those who quote or summarise RR have actually read the suite of papers and understood the methodology and caveats of the work? Not many is my guess. This article by RR – Debt and growth revisited is a good lay summary.

Note that:

1. They analyse all public debt – domestic and foreign-currency.

2. They do not isolate fiat-currency issuing governments with floating exchange rates and let us know what the situation is for that cohort. So there is a complex conflation of important institutional arrangements and economic behaviours.

3. Most importantly, they admit that:

Temporal causality tests are not part of the analysis

They acknowledge that the non-linearity of the relationships being considered make it hard to undertake conventional causality tests. All they are considering are contemporaneous relationships.

Which means? That the analysis provides no reliable guide to policy makers.

Have a look at the Table they provide in the above-cited article. Australia’s real GDP growth rate doubled when Federal debt to GDP jumped across the 90 per cent threshold. Why? Because the deficits were building public infrastructure and wide-spread construction efforts and supporting private saving (so that private spending could be maintained).

Causality? Very clearly -> deficits drove nominal aggregate demand growth in a growing economy and debt rose because of the institutional arrangements in place to match government net spending with private debt issuance.

Then consider say Japan. Its growth rate is obviously lower as the public debt ratio has been above 90 per cent. But in which years were those observations? RR tell us “Japan in the last decade” – a decade marked by the struggle to recover from a devastating collapse in private sector spending and the need to expand budget deficits markedly to maintain some semblance of real GDP growth.

Causality? Obviously, the low growth forced the Japanese government to increase deficits (and increase the debt ratio). That is, the causality is backwards.

If we were to examine the other cases and pick through the historical record (I have done this for a number of the countries covered) then the situation will become very mirky and not the least supportive of RR’s claims that a discretionary move by the government to push up the debt ratio beyond the 90 per cent threshold will undermine growth.

Which means Robert J. Samuelson should be more circumspect in what he says.

Moreover, when he writes:

, imagine that the country had adhered to its balanced-budget tradition before the crisis. Some deficits would have remained, but the cumulative debt would have been much lower: plausibly between 10 percent and 20 percent of GDP. There would have been more room for expansion. Balancing the budget might even have forced Congress to face the costs of an aging society.

… we know he isn’t undertaking any coherent macroeconomic analysis here, but rather spouting the ideology espoused by the Peter G. Peterson and ilk deficit terrorists.

There is no extra “room” for expansion if a nation has a lower deficit (or balanced-budget) to begin a downturn with. The room for expansion is all to do with what real capacity is lying idle and in what currency the goods and services that can be produced with that capacity are for sale.

There is massive room for expansion in the US at present – as evidenced by the persistently high unemployment rate. Does anyone seriously believe that the US government could not offer a job to anyone who wanted it in the US at some credible minimum wage to undertake community work and environmental services (for example) and no-one would turn up to the job depot next morning to claim their wage?

Many might not like that use of the idle labour. There would be inevitable claims that it is wasteful etc. But my bet is that millions would turn up in the first week looking for a job.

That is excess capacity and the US government has unlimited means to deploy it productively. The only constraint is the ideological dislike for such government activity.

Moreover, the US government could embark on a massive public infrastructure development phase (employing the workers above) and revitalise some of the worst parts of its urban infrastructure and see to it that the poor have better housing and means of support.

Does any one out there deny that real GDP would increase – quick smart? Does anyone think that other capitalists would suddenly stop investing because they feared that the deficits would bankrupt the government? My bet is that private investment would jump upwards as firms realised that millions of workers now had wages and were able to improve their real living standards.

My bet is that the pool of government jobs would shrink fairly rapidly (as it did for example in Argentina when the government introduced its Head of Household job guarantee scheme in 2002).

Conclusion

We just have to keep countering this sort of misinformation and providing readers with frameworks in which to place these statements and test their logical coherence.

That is what I try to do with this blog. Nothing much more than that.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2012 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Dear Bill

One reasonable argument for keeping government debt within limits is to prevent interest payments from competing with social expenditures. If the public debt is 200% of GDP and the real rate of interest is 3%, then 6% of GDP has to be taxed in order to pay the interest on the debt. If government expenditures are 40% of GDP, then 15% of the government budget will have to be used to pay the interest on the debt. That is more than health care costs in every country except the US.

Regards. James

@ James Schipper

Or perhaps interest payments could be seen as a form of social expenditure.

Let’s imagine a situation where most investors in government bonds are middle class savers, thinking about their retirement, future health costs, etc.

Then 6% of annual GDP would be transferred to them via interest payments. The middle class would have a higher standard of living than otherwise, and the government could thus safely decide to spend less on health and education in the knowledge that a large chunk of the population now has the means to pay by themselves, based on their higher incomes.

ABS (Australian Bird Statistics)

6102.0.55.001 – Bird Labour Statistics: Concepts, Sources and Methods

2.1 BIRD FRAMEWORK (FOOD SEARCHING)

*See other frameworks for family rearing and singing songs (just for the heck of it) to celebrate being alive.

2.2 BIRDS BEING BIRDS WILL SEARCH FOR FOOD CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

Birds in scope

A) Engaged in being a bird

B) Not engaged in being a bird

i) Actively looking for food

1) Available to look for food

2) Not available to look for food

ii) Not actively looking for food

NOTES:

A) Live birds, happy to be birds at last!

B) Birds with clipped feathers (on the way to being stone-cold dead birds).

i) – Includes clipped birds who despite being steam-rolled by leisure (entertainment) ‘actively’ look for food 1 hour per day;

1) – Includes lazy clipped birds with a bad attitude who pretend to look for food 1 hour per week;

2) – Includes dumb drunk UN-preened clipped birds of whom it has been socially mandated that somebody should feed them because they deliberately only look for food 1 hour per month;

ii) – Includes dead birds and ‘volunteer’ clipped birds who are just ghosts of the Conceptual Framework, and therefore don’t have to be counted anymore thank G.O.D.!

“The door to the cage is open, but this little bird – when will it fly free”. [Kabir – in a different context but transferable nonetheless]

US income tax rates in the 50s and 60s were higher for the wealthy than they are now. So there is “room for expansion”.

@ James Schipper, Jose Guilherme

MMT specifies that taxes do not fund the expenditures of the currency issuer. They merely extinguish the liabilities incurred when the money collected in taxes was created. (This is not as complex as it might appear. Simply set it up as double-entry accounting, and this follows from that in an almost trivial manner.) Taxation then might be thought of as the death of the money collected. Further, all government spending by the issuer must thus be via creation (birth) of new money (and new liabilities).

A similar thing happens when the issuer “borrows” money to fund its expenditures. The “borrowed” money offsets the initial liabilities, but in this case, an equal replacement of the “borrowed” money is created as a government bond. “Green money” (currency) is replaced with “blue money” (bonds), which is better described as a debt swap (or a credit swap if you are the lender), the total liabilities being unchanged from before to after the “borrowing” occurs. (Note: “Green money” is highly liquid, and thus does not pay interest. “Blue money” is less liquid, with holder accepting interest in lieu of this liquidity.)

Of course, this “borrowing” occurs ostensibly to fund expenditures, and when these expenditures are then made, new liabilities are created. The key take-away from this is that these new liabilities (new money creation) occur regardless of whether or not the borrowing transaction occurred. (Again, this is simply double-entry accounting.) Because of this, MMT maintains that borrowing too (in addition to taxation) does not fund the expenditures of the issuer. In both cases, expenditures are always funded via the creation of new money. The “borrowing” transactions are then superfluous, as they provide no additional fiscal space to the issuer, and this is exactly what MMT asserts.

Going on to Jose Guilherme’s response to James Schipper, why then would the issuer even conduct the “borrowing” transactions? As Jose points out, bonds can be used as a kind of risk-free annuity suitable for pension savings, in particular that portion of pension saving nearing its due date for payout. These near-term liabilities on the pension fund are thus guaranteed, simplifying and solidifying the pension managers’ obligations for near-term payments. It is important to note that the interest payments on these bonds are also made with new money, and thus have no impact on the taxation and “borrowing” policies of the issuer. They do not take away from either the issuers’ current or future spending plans.

In all of this of course, the issuer must always be on guard against any inflationary pressures that might arise, but the mainstream formulation for inflation (printing money = inflation) is incorrect, and best ignored. The MMT formulation, that inflation is driven by capacity issues, is far better, and should be used in place of the mainstream formulation.

@ James Schipper, Jose Guilherme

Why do you conflate deficit spending and debt? Sureley there’s no need match deficit spending with debt, is there?

Isn’t it the case that deficit spending is to maintain aggregated demand and therefore full employment, while issuing government debt is about maintaining a level of bank reserves?

Or perhaps interest payments could be seen as a form of social expenditure. Jose Guilherme

It’s “corporate welfare”, according to Bill. How can that be good except to fascists? If people need welfare then let’s give it to them generously, not pretend that they are earning interest on what monetarily sovereign governments have no need to borrow in the first place. It also hurts our exports when foreigners can earn a risk-free return on their export earnings instead of purchasing what we export? Aren’t our exports being “crowded out” by sales of sovereign debt to foreigners?

Anyway, borrowing by monetary sovereigns stinks. Alexander Hamilton as much as admitted that it’s purpose is to bribe the rich into supporting the national government. That need is long past in the US.

while issuing government debt is about maintaining a level of bank reserves? Tristan Lanfrey

That’s more fascism, isn’t it? Why the heck should the government regulate the amount of reserves that the banks have?

There is enough money in the American economy, but most of it is held by the rich. This explains the low level of aggregate demand that is prolonging this recession.

We’re not going to convince the rich to give more of their wealth to people who need it, so the solution is more government spending. I just hope that money does not mostly get snatched by the rich again.

@ Benedict@Large

“As Jose points out, bonds can be used as a kind of risk-free annuity suitable for pension savings…”.

That’s right. The government, by issuing Treasury bonds, is providing individuals with an important investment option. By buying or not buying bonds individuals may choose between consumption in the present or later in life. If they prefer to bet on a higher standard of living after retirement (admitting they get their forecasts right and are still alive and well after, say, age 65) they will buy a high amount of bonds during their professional lives and then “live on interest” after retirement.

@ Tristan Lanfrey

I’m not conflating at all deficit spending and debt. I’m just saying that a monetarily sovereign government may freely choose to keep issuing bonds not to finance itself but only in order to provide an extra risk-free vehicle where the middle class may park its savings.

@ F. Beard

It’s not necessarily corporate welfare, it all depends on who’s buying the bonds.

If you want to prevent corporations from having access to this type of securities, fine. Just pass a law stipulating that they may be sold to individuals exclusively, perhaps on the Treasury web site.

I would agree with Tyler in this sense. Discussing the US economy without addressing the concentration of wealth and income misses the biggest part of the picture. When a small portion of the population holds that much wealth they can’t find good places to invest any more and turn to speculation. It’s happened twice now.

Just pass a law stipulating that they may be sold to individuals exclusively, perhaps on the Treasury web site. Jose Guilherme

Not good enough. That’s still benefiting some (typically the rich) at the expense of others. We all pay taxes directly or indirectly (including the “stealth inflation tax”) but not every one can afford to buy bonds or at least to the same extent as the rich can.

If people need a guaranteed income stream at retirement, then let the government provide it as needed. Beyond that, they can take their risks with private investments. And once the troublesome nationwide boom-bust cycle is abolished along with other government support for banking then private investing should be a lot safer.

“If people need a guaranteed income stream at retirement, then let the government provide it as needed. Beyond that, they can take their risks with private investments”.

F. Beard

I agree the government should provide for a minimum, a floor for every citizen. But why deny people the possibility of choosing extra income at retirement by making sacrifices in the present, through postponing consumption via buying T bonds?

Plus, this would have the advantage of not forcing middle class people to invest (some would say, speculate) in shares with the purpose of providing for retirement. We all saw the disastrous effects of such behaviour in the USA: millions of soon-to-be pensioners watching their savings being literally wiped out in a catastrophic stock market crash.

As for truly rich people, they will likely still prefer the stock market and hedge funds.

But why deny people the possibility of choosing extra income at retirement by making sacrifices in the present, through postponing consumption via buying T bonds? Jose Guilherme

People should be able to save risk-free in nominal terms. And a monetarily sovereign government (Who else possibly could?) should provide that service for its fiat. And that service should be free up to normal household limits. But the government should not pay interest for those savings (nor should it lend them out).

And people should be able to save risk-free in real terms too but that is not possible to guarantee unless unconscionable limits on money creation are imposed.

But as for receiving a real return that should require real investment which requires real risk taking.

But under the current debt money system the clearing banks get a cut of the surplus for nothing….nothing.

The Note is as good as the Bond.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yAdUtAl6elM

Has anyone formalized a blue money-green money system which divides the two properties of money, a measure of value for transactions and a store of value for savings? Green money would have a shelf life and could be converted to blue by paying a conversion tax. Blue money would have a generous lifetime cap and be an opportunity fund, a saving fund or a safety net fund. There would be credit with a shelf life but no interest and no opportunity to plunder unearned or future income. Wealth would be earned and the system a reincarnation of the American Dream.