Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

Saturday Quiz – September 29, 2012 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for yesterday’s quiz. The information provided should help you understand the reasoning behind the answers. If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

Assume a nation is running an external surplus equivalent to 2 per cent of GDP and the government manages to run a budget surplus equivalent to 1 per cent of GDP. The national income changes associated with these balances would ensure that the private domestic sector was running an overall deficit of 1 per cent of GDP.

The answer is False.

This question requires an understanding of the sectoral balances that can be derived from the National Accounts. But it also requires some understanding of the behavioural relationships within and between these sectors which generate the outcomes that are captured in the National Accounts and summarised by the sectoral balances.

We know that from an accounting sense, if the external sector overall is in deficit, then it is impossible for both the private domestic sector and government sector to run surpluses. One of those two has to also be in deficit to satisfy the accounting rules.

The important point is to understand what behaviour and economic adjustments drive these outcomes.

So here is the accounting (again). The basic income-expenditure model in macroeconomics can be viewed in (at least) two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of spending; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the income produced. Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances.

From the sources perspective we write:

GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

From the uses perspective, national income (GDP) can be used for:

GDP = C + S + T

which says that GDP (income) ultimately comes back to households who consume (C), save (S) or pay taxes (T) with it once all the distributions are made.

Equating these two perspectives we get:

C + S + T = GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

So after simplification (but obeying the equation) we get the sectoral balances view of the national accounts.

(I – S) + (G – T) + (X – M) = 0

That is the three balances have to sum to zero. The sectoral balances derived are:

- The private domestic balance (I – S) – positive if in deficit, negative if in surplus.

- The Budget Deficit (G – T) – negative if in surplus, positive if in deficit.

- The Current Account balance (X – M) – positive if in surplus, negative if in deficit.

These balances are usually expressed as a per cent of GDP but that doesn’t alter the accounting rules that they sum to zero, it just means the balance to GDP ratios sum to zero.

A simplification is to add (I – S) + (X – M) and call it the non-government sector. Then you get the basic result that the government balance equals exactly $-for-$ (absolutely or as a per cent of GDP) the non-government balance (the sum of the private domestic and external balances).

This is also a basic rule derived from the national accounts and has to apply at all times.

So what economic behaviour might lead to the outcome specified in the question?

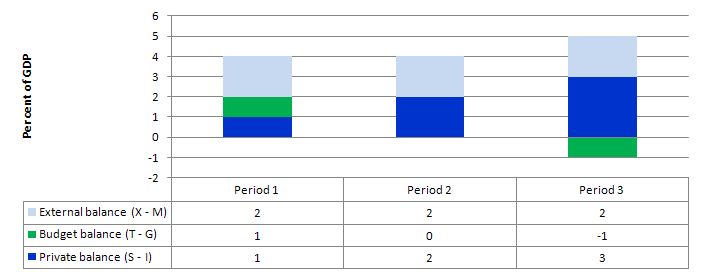

The following graph shows three situations where the external sector is in surplus of 2 per cent of GDP (note I have written the budget balance as (T – G).

The data in Period 1 describes the situation outlined in the question. You will note that with the government budget in surplus (of 1 per cent of GDP) the private domestic balance is in surplus (1 per cent of GDP). The net injection to demand from the external sector (equivalent to 2 per cent of GDP) is sufficient to “fund” the private saving drain from expenditure without compromising economic growth. The growth in income would also allow the budget to be in surplus (via tax revenue).

In Period 2, the rise in private domestic saving drains extra aggregate demand and necessitates a more expansionary position from the government (relative to Period 1), which in this case manifests as a balanced public budget.

Period 3, relates to the data presented in the question – an external surplus of 2 per cent of GDP and private domestic saving equal to 3 per cent of GDP. Now the demand injection from the external sector is being more than offset by the demand drain from private domestic saving. The income adjustments that would occur in this economy would then push the budget into deficit of 1 per cent of GDP.

The movements in income associated with the spending and revenue patterns will ensure these balances arise.

The general rule is that the government budget deficit (surplus) will always equal the non-government surplus (deficit).

So if there is an external surplus that is greater than private domestic sector saving (a surplus) then there will always be a budget surplus. Equally, the higher the private saving is relative to the external surplus, the larger the budget deficit.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Barnaby, better to walk before we run

- Stock-flow consistent macro models

- Norway and sectoral balances

- The OECD is at it again!

Question 2:

Starting from the external situation in Question 1, with the surplus being the equivalent of 2 per cent of GDP but this time the budget surplus is currently 2 per cent of GDP. If the budget balance stays constant and the external surplus rises to the equivalent of 4 per cent of GDP then you can conclude that national income also rises and the private surplus moves from minus 2 per cent of GDP to plus 2 per cent of GDP.

The answer is False.

Please refer to the explanation in Question 1 for the conceptual material required to understand this question and answer.

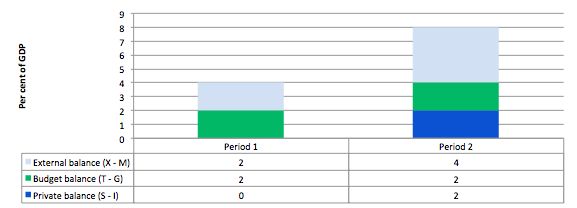

Consider the following graph and accompanying table which depicts two periods outlined in the question.

In Period 1, with an external surplus of 2 per cent of GDP and a budget surplus of 2 per cent of GDP the private domestic balance is zero. The demand injection from the external sector is exactly offset by the demand drain (the fiscal drag) coming from the budget balance and so the private sector can neither net save overall nor spend more than its earns. So the starting position for the private domestic sector is a balanced state.

In Period 2, with the external sector adding more to demand now – surplus equal to 4 per cent of GDP and the budget balance unchanged (this is stylised – in the real world the budget will certainly change), there is a stimulus to spending and national income would rise.

The rising national income also provides the capacity for the private sector to save overall and so they can now save 2 per cent of GDP. Please note the difference between saving and saving overall.

The fiscal drag is overwhelmed by the rising net exports.

This is a highly stylised example and you could tell a myriad of stories that would be different in description but none that could alter the basic point.

If the drain on spending (from the public sector) is more than offset by an external demand injection, then GDP rises and the private sector overall saving increases.

If the drain on spending from the budget outweighs the external injections into the spending stream then GDP falls (or growth is reduced) and the overall private balance would fall into deficit.

You may wish to read the following blogs for more information:

- Back to basics – aggregate demand drives output

- Stock-flow consistent macro models

- Norway and sectoral balances

- The OECD is at it again!

- Barnaby, better to walk before we run

- Saturday Quiz – June 19, 2010 – answers and discussion

Question 3:

If all bank loans had to be backed by reserves held at the bank (a 100 per cent reserve requirement) then the capacity of the banks to lend would be more constrained which would help maintain financial stability.

The answer is False.

In a “fractional reserve” banking system of the type the US runs (which is really one of the relics that remains from the gold standard/convertible currency era that ended in 1971), the banks have to retain a certain percentage (10 per cent currently in the US) of deposits as reserves with the central bank. You can read about the fractional reserve system from the Federal Point page maintained by the FRNY.

Where confusion as to the role of reserve requirements begins is when you open a mainstream economics textbooks and “learn” that the fractional reserve requirements provide the capacity through which the private banks can create money. The whole myth about the money multiplier is embedded in this erroneous conceptualisation of banking operations.

The FRNY educational material also perpetuates this myth. They say:

If the reserve requirement is 10%, for example, a bank that receives a $100 deposit may lend out $90 of that deposit. If the borrower then writes a check to someone who deposits the $90, the bank receiving that deposit can lend out $81. As the process continues, the banking system can expand the initial deposit of $100 into a maximum of $1,000 of money ($100+$90+81+$72.90+…=$1,000). In contrast, with a 20% reserve requirement, the banking system would be able to expand the initial $100 deposit into a maximum of $500 ($100+$80+$64+$51.20+…=$500). Thus, higher reserve requirements should result in reduced money creation and, in turn, in reduced economic activity.

This is not an accurate description of the way the banking system actually operates and the FRNY (for example) clearly knows their representation is stylised and inaccurate. Later in the same document they they qualify their depiction to the point of rendering the last paragraph irrelevant. After some minor technical points about which deposits count to the requirements, they say this:

Furthermore, the Federal Reserve operates in a way that permits banks to acquire the reserves they need to meet their requirements from the money market, so long as they are willing to pay the prevailing price (the federal funds rate) for borrowed reserves. Consequently, reserve requirements currently play a relatively limited role in money creation in the United States.

In other words, the required reserves play no role in the credit creation process.

The actual operations of the monetary system are described in this way. Banks seek to attract credit-worthy customers to which they can loan funds to and thereby make profit. What constitutes credit-worthiness varies over the business cycle and so lending standards become more lax at boom times as banks chase market share (this is one of Minsky’s drivers).

These loans are made independent of the banks’ reserve positions. Depending on the way the central bank accounts for commercial bank reserves, the latter will then seek funds to ensure they have the required reserves in the relevant accounting period. They can borrow from each other in the interbank market but if the system overall is short of reserves these “horizontal” transactions will not add the required reserves. In these cases, the bank will sell bonds back to the central bank or borrow outright through the device called the “discount window”.

At the individual bank level, certainly the “price of reserves” will play some role in the credit department’s decision to loan funds. But the reserve position per se will not matter. So as long as the margin between the return on the loan and the rate they would have to borrow from the central bank through the discount window is sufficient, the bank will lend.

So the idea that reserve balances are required initially to “finance” bank balance sheet expansion via rising excess reserves is inapplicable. A bank’s ability to expand its balance sheet is not constrained by the quantity of reserves it holds or any fractional reserve requirements. The bank expands its balance sheet by lending. Loans create deposits which are then backed by reserves after the fact. The process of extending loans (credit) which creates new bank liabilities is unrelated to the reserve position of the bank.

The major insight is that any balance sheet expansion which leaves a bank short of the required reserves may affect the return it can expect on the loan as a consequence of the “penalty” rate the central bank might exact through the discount window. But it will never impede the bank’s capacity to effect the loan in the first place.

The money multiplier myth leads students to think that as the central bank can control the monetary base then it can control the money supply. Further, given that inflation is allegedly the result of the money supply growing too fast then the blame is sheeted home to the “government” (the central bank in this case).

The reality is that the reserve requirements that might be in place at any point in time do not provide the central bank with a capacity to control the money supply.

So would it matter if reserve requirements were 100 per cent? In this blog – 100-percent reserve banking and state banks – I discuss the concept of a 100 per cent reserve system which is favoured by many conservatives who believe that the fractional reserve credit creation process is inevitably inflationary.

There are clearly an array of configurations of a 100 per cent reserve system in terms of what might count as reserves. For example, the system might require the reserves to be kept as gold. In the old “Giro” or “100 percent reserve” banking system which operated by people depositing “specie” (gold or silver) which then gave them access to bank notes issued up to the value of the assets deposited. Bank notes were then issued in a fixed rate against the specie and so the money supply could not increase without new specie being discovered.

Another option might be that all reserves should be in the form of government bonds, which would be virtually identical (in the sense of “fiat creations”) to the present system of central bank reserves.

While all these issues are interesting to explore in their own right, the question does not relate to these system requirements of this type. It was obvious that the question maintained a role for central bank (which would be unnecessary in a 100-per cent reserve system based on gold, for example.

It is also assumed that the reserves are of the form of current central bank reserves with the only change being they should equal 100 per cent of deposits.

We also avoid complications like what deposits have to be backed by reserves and assume all deposits have to so backed.

In the current system, the the central bank ensures there are enough reserves to meet the needs generated by commercial bank deposit growth (that is, lending). As noted above, the required reserve ratio has no direct influence on credit growth. So it wouldn’t matter if the required reserves were 10 per cent, 0 per cent or 100 per cent.

In a fiat currency system, commercial banks require no reserves to expand credit. Even if the required reserves were 100 per cent, then with no other change in institutional structure or regulations, the central bank would still have to supply the reserves in line with deposit growth.

You might like to read these blogs for further information:

- Lending is capital- not reserve-constrained

- Oh no … Bernanke is loose and those greenbacks are everywhere

- Building bank reserves will not expand credit

- Building bank reserves is not inflationary

- 100-percent reserve banking and state banks

- Money multiplier and other myths

Question 4:

A sovereign currency-issuing government needs to raise tax revenue to implement and provision its socio-economic agenda.

The answer is True.

First, to clear the ground we state clearly that a sovereign government is the monopoly issuer of the currency and is never revenue-constrained. So the question is not about the tax revenue per se but rather the role taxes play in the monetary system. A sovereign government never has to “obey” the constraints that the private sector always has to obey.

The foundation of many mainstream macroeconomic arguments is the fallacious analogy they draw between the budget of a household/corporation and the government budget. However, there is no parallel between the household (for example) which is clearly revenue-constrained because it uses the currency in issue and the national government, which is the issuer of that same currency.

The choice (and constraint) sets facing a household and a sovereign government are not alike in any way, except that both can only buy what is available for sale. After that point, there is no similarity or analogy that can be exploited.

Of-course, the evolution in the 1960s of the literature on the so-called government budget constraint (GBC), was part of a deliberate strategy to argue that the microeconomic constraint facing the individual applied to a national government as well. Accordingly, they claimed that while the individual had to “finance” its spending and choose between competing spending opportunities, the same constraints applied to the national government. This provided the conservatives who hated public activity and were advocating small government, with the ammunition it needed.

So the government can always spend if there are goods and services available for purchase, which may include idle labour resources. This is not the same thing as saying the government can always spend without concern for other dimensions in the aggregate economy.

For example, if the economy was at full capacity and the government tried to undertake a major nation building exercise then it might hit inflationary problems – it would have to compete at market prices for resources and bid them away from their existing uses.

In those circumstances, the government may – if it thought it was politically reasonable to build the infrastructure – quell demand for those resources elsewhere – that is, create some unemployment. How? By increasing taxes.

So to answer the question correctly, you need to understand the role that taxes play in a fiat currency system.

In a fiat monetary system the currency has no intrinsic worth. Further the government has no intrinsic financial constraint. Once we realise that government spending is not revenue-constrained then we have to analyse the functions of taxation in a different light. The starting point of this new understanding is that taxation functions to promote offers from private individuals to government of goods and services in return for the necessary funds to extinguish the tax liabilities.

In this way, it is clear that the imposition of taxes creates unemployment (people seeking paid work) in the non-government sector and allows a transfer of real goods and services from the non-government to the government sector, which in turn, facilitates the government’s economic and social program.

The crucial point is that the funds necessary to pay the tax liabilities are provided to the non-government sector by government spending. Accordingly, government spending provides the paid work which eliminates the unemployment created by the taxes.

So it is now possible to see why mass unemployment arises. It is the introduction of State Money (government taxing and spending) into a non-monetary economics that raises the spectre of involuntary unemployment. As a matter of accounting, for aggregate output to be sold, total spending must equal total income (whether actual income generated in production is fully spent or not each period). Involuntary unemployment is idle labour offered for sale with no buyers at current prices (wages).

Unemployment occurs when the private sector, in aggregate, desires to earn the monetary unit of account, but doesn’t desire to spend all it earns, other things equal. As a result, involuntary inventory accumulation among sellers of goods and services translates into decreased output and employment. In this situation, nominal (or real) wage cuts per se do not clear the labour market, unless those cuts somehow eliminate the private sector desire to net save, and thereby increase spending.

The purpose of State Money is for the government to move real resources from private to public domain. It does so by first levying a tax, which creates a notional demand for its currency of issue. To obtain funds needed to pay taxes and net save, non-government agents offer real goods and services for sale in exchange for the needed units of the currency. This includes, of-course, the offer of labour by the unemployed. The obvious conclusion is that unemployment occurs when net government spending is too low to accommodate the need to pay taxes and the desire to net save.

This analysis also sets the limits on government spending. It is clear that government spending has to be sufficient to allow taxes to be paid. In addition, net government spending is required to meet the private desire to save (accumulate net financial assets). From the previous paragraph it is also clear that if the Government doesn’t spend enough to cover taxes and desire to save the manifestation of this deficiency will be unemployment.

Keynesians have used the term demand-deficient unemployment. In our conception, the basis of this deficiency is at all times inadequate net government spending, given the private spending decisions in force at any particular time.

So the answer should now be obvious. If the economy is to fulfill its political mandate it must be able to transfer real productive resources from the private sector to the public sector. Taxation is the vehicle that a sovereign government uses to “free up resources” so that it can use them itself. But taxation has nothing to do with “funding” of the government spending.

To understand how taxes are used to attenuate demand please read this blog – Functional finance and modern monetary theory.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- The budget deficits will increase taxation!

- Will we really pay higher taxes?

- A modern monetary theory lullaby

- Functional finance and modern monetary theory

- Deficit spending 101 – Part 1

- Deficit spending 101 – Part 2

- Deficit spending 101 – Part 3

Premium Question 5:

Assume a nation’s central bank successfully maintains a zero interest rate policy and recession keeps the inflation rate at zero. Under these circumstances a fiscal austerity program can achieve reductions in the public debt ratio even if the movements in the automatic stabilisers that result from the recession that the austerity causes tax revenue to decline.

The answer is True.

First, some background.

While Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) places no particular importance in the public debt to GDP ratio for a sovereign government, given that insolvency is not an issue, the mainstream debate is dominated by the concept.

The unnecessary practice of fiat currency-issuing governments of issuing public debt $-for-$ to match public net spending (deficits) ensures that the debt levels will rise when there are deficits.

Rising deficits usually mean declining economic activity (especially if there is no evidence of accelerating inflation) which suggests that the debt/GDP ratio may be rising because the denominator is also likely to be falling or rising below trend.

Further, historical experience tells us that when economic growth resumes after a major recession, during which the public debt ratio can rise sharply, the latter always declines again.

It is this endogenous nature of the ratio that suggests it is far more important to focus on the underlying economic problems which the public debt ratio just mirrors.

However, mainstream economics starts with the analogy between the household and the sovereign government such that any excess in government spending over taxation receipts has to be “financed” in two ways: (a) by borrowing from the public; and/or (b) by “printing money”.

This basic analogy is flawed at its most elemental level. The household must work out the financing before it can spend. The household cannot spend first. The government can spend first and ultimately does not have to worry about financing such expenditure.

However, in mainstream framework for analysing these so-called “financing” choices is called the government budget constraint (GBC). The GBC says that the budget deficit in year t is equal to the change in government debt over year t plus the change in high powered money over year t. So in mathematical terms it is written as:

Which you can read in English as saying that Budget deficit = Government spending + Government interest payments – Tax receipts must equal (be “financed” by) a change in Bonds (B) and/or a change in high powered money (H). The triangle sign (delta) is just shorthand for the change in a variable.

However, this is merely an accounting statement. In a stock-flow consistent macroeconomics, this statement will always hold. That is, it has to be true if all the transactions between the government and non-government sector have been corrected added and subtracted.

So in terms of MMT, the previous equation is just an ex post accounting identity that has to be true by definition and has not real economic importance.

But for the mainstream economist, the equation represents an ex ante (before the fact) financial constraint that the government is bound by. The difference between these two conceptions is very significant and the second (mainstream) interpretation cannot be correct if governments issue fiat currency (unless they place voluntary constraints on themselves to act as if it is).

Further, in mainstream economics, money creation is erroneously depicted as the government asking the central bank to buy treasury bonds which the central bank in return then prints money. The government then spends this money. This is called debt monetisation and you can find out why this is typically not a viable option for a central bank by reading the Deficits 101 suite – Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 3.

Anyway, the mainstream claims that if governments increase the money growth rate (they erroneously call this “printing money”) the extra spending will cause accelerating inflation because there will be “too much money chasing too few goods”! Of-course, we know that proposition to be generally preposterous because economies that are constrained by deficient demand (defined as demand below the full employment level) respond to nominal demand increases by expanding real output rather than prices. There is an extensive literature pointing to this result.

So when governments are expanding deficits to offset a collapse in private spending, there is plenty of spare capacity available to ensure output rather than inflation increases.

But not to be daunted by the “facts”, the mainstream claim that because inflation is inevitable if “printing money” occurs, it is unwise to use this option to “finance” net public spending.

Hence they say as a better (but still poor) solution, governments should use debt issuance to “finance” their deficits. They also claim this is a poor option because in the short-term it is alleged to increase interest rates and in the longer-term is results in higher future tax rates because the debt has to be “paid back”.

Neither proposition bears scrutiny – you can read these blogs – Will we really pay higher taxes? and Will we really pay higher interest rates? – for further discussion on these points.

A primary budget balance is the difference between government spending (excluding interest rate servicing) and taxation revenue.

The standard mainstream framework, which even the so-called progressives (deficit-doves) use, focuses on the ratio of debt to GDP rather than the level of debt per se. The following equation captures the approach:

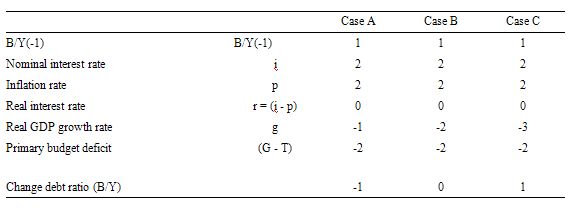

So the change in the debt ratio is the sum of two terms on the right-hand side: (a) the difference between the real interest rate (r) and the GDP growth rate (g) times the initial debt ratio; and (b) the ratio of the primary deficit (G-T) to GDP.

The real interest rate is the difference between the nominal interest rate and the inflation rate.

The standard formula above can easily demonstrate that a nation running a primary deficit can reduce its public debt ratio over time as long as economic growth is strong enough.

Furthermore, depending on contributions from the external sector, a nation running a deficit will more likely create the conditions for a reduction in the public debt ratio than a nation that introduces an austerity plan aimed at running primary surpluses.

But it is also true that an austerity package which damages real growth can also reduce the public debt ratio.

That is the focus of this question. Assumes:

- Current public debt to GDP ratio is 100 per cent = 1. This assumption doesn’t alter the conclusion it just makes the numbers easy.

- Nominal interest rate (i) and the inflation rate (p) remain constant and zero, which means the real interest rate (r = i – p) = 0.

The following Table shows three cases:

- Case A – primary budget surplus to GDP ratio exceeds the negative GDP growth rate.

- Case B – primary budget to GDP ratio is equal to the negative GDP growth rate.

- Case C – primary budget to GDP ratio is less than the negative GDP growth rate.

The case in question is Case A.

In Case A, the primary budget surplus to GDP ratio (2 per cent – note it is presented as a negative figure given that the budget balance is presented as [G – T]) exceeds the negative GDP growth rate (-1 per cent). In this case, the debt ratio falls by the difference (given the real interest rate is zero).

As long as the primary surplus as a per cent of GDP is exactly equal to the negative GDP growth rate (Case B), there can be no reduction in the public debt ratio. This is because what is being added proportionately to the numerator of the ratio is also being added to the denominator.

Under Case C where the primary budget surplus is 2 per cent and the contraction in real GDP is 3 percent for the debt ratio rises by the difference.

How likely is it that Case A would occur in the real world when the government was pursuing such a fiscal path? Answer: unlikely.

First, fiscal austerity will probably push the GDP growth rate further into negative territory which, other things equal, pushes the public debt ratio up. Why? The budget balance is endogenous (that is, depends on private activity levels) because of the importance of the automatic stabilisers.

As GDP contracts, tax revenue falls and welfare outlays rise. It is highly likely that the government would not succeed in achieving a budget surplus under these circumstances.

So as GDP growth declines further, the automatic stabilisers will push the balance result towards (and into after a time) deficit, which, given the borrowing rules that governments volunatarily enforce on themselves, also pushed the public debt ratio up.

So austerity packages, quite apart from their highly destructive impacts on real standards of living and social standards, typically fail to reduce public debt ratios and usually increase them.

So even if you were a conservative and erroneously believed that high public debt ratios were the devil’s work, it would be foolish (counter-productive) to impose fiscal austerity on a nation as a way of addressing your paranoia. Better to grit your teeth and advocate higher deficits and higher real GDP growth.

That strategy would also be the only one advocated by MMT.

Just a quibble perhaps, but wouldn’t question 4 be clearer if it read that gov’t needs to “levy taxes” rather than “raise tax revenues” which could imply increasing them?

Also, I had the following letter published in a local newspaper:

Stimulus, not austerity, is what Canada needs

The Daily News, September 29, 2012

Fiscal difficulties of the provinces are a result not only of direct federal downloading, but also of federal austerity.

As long as Canada imports more than it exports, and our private sector wants to net save, there will be a purchasing power gap.

This gap has to be filled by federal deficits or the economy will spiral downward with a consequent loss of tax revenues at all levels.

The evidence is clear in the Euro-zone where attempts to balance national budgets through contraction have failed, and have led to mass unemployment and riots in the streets.

The welfare of Canadians will be enhanced when the Conservative government spends money and puts people to work – not by irresponsible budget cuts that terminate jobs and jeopardize our health and safety.

Larry Kazdan, Vancouver

© Copyright (c) Postmedia News

By the way, there is a big scandal in Canada right now, because we have had an e-coli outbreak in meat, which may be linked to gov’t cutbacks of meat inspectors and lab scientists.

Bill,

A little disappointed in #3 reply.

As I wrote to the question yesterday, the work of IMF researchers Benes and Kumhof found that resort to full-reserve banking, as proposed IN the Chicago Plan and later supported by Fisher in his “100 Percent Money” and academic textbooks on full-reserve banking, would result in exactly the changes postulated in the question:

1. bank lending would be reduced ( a reduction in private sector debt),

2. This would lead to greater financial and economic stability.

This IMF Working Paper Begins:

” Abstract

At the height of the Great Depression a number of leading U.S. economists advanced a

proposal for monetary reform that became known as the Chicago Plan. It envisaged the

separation of the monetary and credit functions of the banking system, by requiring 100%

reserve backing for deposits. Irving Fisher (1936) claimed the following advantages for this

plan:

(1) Much better control of a major source of business cycle fluctuations, sudden

increases and contractions of bank credit and of the supply of bank-created money.

(2) Complete elimination of bank runs.

(3) Dramatic reduction of the (net) public debt.

(4) Dramatic reduction of private debt, as money creation no longer requires simultaneous

debt creation.

We study these claims by embedding a comprehensive and carefully calibrated model of the banking system in a DSGE model of the U.S. economy.

We find support for all four of Fisher’s claims. Furthermore, output gains approach 10 percent, and steady state inflation can drop to zero without posing problems for the conduct of monetary policy.”

END

Isn’t it time for all MMT to recognize the reality that 100 Percent Money and full-reserve banking are not merely throwbacks to the era of a gold-standard, and that these actually represent an effort of learned, progressive economists to replace the gold-standard with a method for stabilizing the purchasing power of the currency?

The IMF research report is evidence of the real socio-economic benefits available by a true reform to the money system, one which actually accomplishes that to which MMT ascribes.

Respectfully.

Sorry, I was dumb enough to comment on the quiz before reading your explanations here. But however, I still have huge problems with #3 and #4. If both these aspects are important then you may want to use (if at all possible) a somewhat clearer approach. E.g., explaining #4 you state “But taxation has nothing to do with “funding” of the government spending.” That was _exactly_ what was on my mind when thinking about #4 – but nevertheless I got it wrong and “earned” the accusation of being too neo-liberal… not the nice way 😉 Anyways, I appreciate your work and effort a lot and am looking forward to further debriefings.

“We study these claims by embedding a comprehensive and carefully calibrated model of the banking system in a DSGE model of the U.S. economy.”

DSGE doesn’t model the US Economy. It models a economist’s fantasy world that has no relationship in the real world.

Re: You can read about the fractional reserve system from the Federal Point page maintained by the FRNY.

This link doesn’t work.

how do you quantify the desire of the private sector to save?

if the majority of the people say wanted the net savings of the 1%

how much government defecits would be neccessary ?

To Neil Wilson.

Glad you read that far through.

Really.

Dr. Kumhof presented his paper last week in Chicago.

He expects blatant DSGE criticism.

He can only work with what the IMF has as its national macro-economic model.

Steve Keen was there.

He had zero criticism of Dr. Kumhof’s work, which was superior to Keen’s.

Finally, Dr. Kaoru Yamaguchi presented his internationally-recognized Systems-Dynamic modeling of an open economy using non-debt based money and came to the same conclusions as Dr. Kumhof.

An internationally accepted central bank DSGE model.

An internationally-recognized Systems-Dynamics based Open-economy model.

What do you have?

FYI, Dr. Kumhof stated that he welcomes professional criticism and discussion of the work, co-authored by Dr. Jaromir Benes. In fact he is seeking it out.

Please do.

I believe you can find him in the IMF book.

Thanks.

You are very fond of appeals to authority. You do realise that is a logical fallacy. It does not strengthen the argument.

“In fact he is seeking it out.”

How about he’s never worked in a Building Society in the real world.

Money is naturally endogenous. Therefore you have to have an enforceable way of stopping that from happening if you want to stop the acceleration effect of debt.

100% reserves doesn’t do that, because I can still obtain the reserves after the fact and make the shortage somebody else’s problem due to the dynamic nature of funding flows. So I can internalise the profits and socialise the losses.

And I do that (roughly) by selling loans at a slightly higher price, or by taking a slightly lower turn, which allows me to ‘poach’ savings from other institutions. Very quickly the system will become systemically short of reserves and it will be very difficult to see where that shortage emanated. So you will get the wild gyrations of interest rates that we got during the monetarist experiments of the 1980s – because ultimately you are trying to control volume in a dynamic system.

I live in Halifax, UK. Halifax was the largest Building Society in the world. The techniques for aggressively expanding a loan book while reserve constrained were developed here. I know the people that did it and retired very well out of it.

So it’s not that a ‘loanable funds’ world wouldn’t look more stable, it’s that the real world isn’t loanable funds and its very difficult to put the real world endogenous system in that box.

From a system perspective that means that the control function should work with the natural endogenous structure rather than trying to fight it by pretending that it isn’t. Then it has more chance of working properly.

Neil,

Thanks for that.

Couple of things.

First, your earlier comment – about DSGE models. The public attacks on DSGE are voluminous – pointedly Keen’s on Krugman. That is why I mentioned Keen’s presence.

Perhaps you read further on the IMF’s revision to DSGE that “by embedding a comprehensive and carefully calibrated model of the banking system” (which includes the CB) the authors have overcome all of the valid primary objections.

Certainly Economics-debunker Keen saw clearly that the study had corrected the common DSGE flaws, producing outputs that had a primary metric for both public and private debt.

At that point, Neil, all DSGE criticisms become merely rhetorical.

“Money is naturally endogenous”.

Says who? Why so?

Read Soddy on the nature of money and explain his errors.

Money is a legal, social construct and its debt-based endogeneity has ruined the global economy. We are drowning in a sea of endogenously-produced debt, all of it created by private bankers from a wealth-concentrating privilege that is undeserved.

Pity the quasi-progressive, heterodox-econ MMT community has no grasp of this reality.

Next, on whether the ending of pro-cyclicality is possible using the proposed reforms:

“First, banks that are subject to a 100% reserve requirement know that they cannot create their own funds to fuel a lending boom, but that instead they have to borrow these funds from the government at rates that increase in a lending boom, and that the additional borrowing could furthermore be subject to much higher capital requirements.” (CPR, at IV.5; pg 42).

Neil, please give up this leftover notion that full-reserve banking allows the endogenous nature of money to continue. A closer read of the Benes-Kumhof paper would show this is not true. Banks can NOT lend and then go borrow their reserves.

The bank MUST have the deposits in order to make the loan and they can only obtain those deposits by borrowing real money from either depositors, other banks or the government.

Please digest the post-transition prudential requirements.

The object is to control the quantity of money, and allow credit to be bank-determined using that money.

Finally, Neil, your critique of my appeal to “authority” is so far off base. If you only knew ….

Rather I have publicly taken the IMF ‘authority’ to task on its blog for not, in its pursuit of global financial stability, acknowledging the work of Benes and Kumhof , who are the personal, courageous actors here.

I know that Dr. Kumhof is an alum of the London Banking School and formerly worked for Barclays, later teaching international banking and finance at Stanford, prior to joining the IMF.

Sorry, Neil, but its a telling point when the discussion evolves to shooting the messenger, rather than addressing the specific content of the message.

The Chicago Plan Revisited can become a cornerstone of the debate around needed reforms to the global money system. My request would be for an informed critique based on its content, and not repetition of outdated and irrelevant rhetoric.

Thanks.

“Certainly Economics-debunker Keen saw clearly that the study had corrected the common DSGE flaws, producing outputs that had a primary metric for both public and private debt.”

You can’t correct the DSGE model. It is fundamentally flawed at the deepest level. It does not reflect the real world economy. Hence why Steve is building a different model in conjunction with the mathematicians at Toronto and with feedback from the MMT economists.

Steve’s presence somewhere doesn’t validate anything.

“Neil, please give up this leftover notion that full-reserve banking allows the endogenous nature of money to continue.”

As I have pointed out. Full reserve banking is precisely what UK building societies did and have done for about 150 years using a lend long, borrow short model. Halifax became the biggest building society in the world by pushing that model to its limits.

Where you have an intermediary in the way you have the capability to buffer and break a coincidence of wants. The timing elements between those two halves can be exploited to push a loan book regardless of the alleged restrictions on the institutions.

Now that is the reality of the world. A cold hard commercial reality of extremely clever people looking to make maximum profits. What you are suggesting will not work to constrain anything because it is very easily manipulated. A manipulation that has already happened in practice in more constrained regulatory environments.

100% reserves works no better than reserve requirements or capital ratios. They are all as easily twisted as each other . If you want a world of loanable funds you literally have to take the lending institution out of the middle of the arrangement and make them agent playing merely a matching role. Everything has to be done in a ‘Zopa’ like environment with maturity matching and no possibility to save at interest without a matching loan requirement. Storage and transactions have to be with and via an institution that *cannot* lend – preferably an offshoot of the central bank.

You are very welcome to believe in something as much as you want. But unfortunately you need a little more than pure faith to make a system work in the real world.

Neil.

Again, thanks.

I agree with much of what you wrote about how a restructured, fully-reserved banking system would operate.

Banks that would hold demand-deposit accounts ARE merely storing and transacting the commerce of their depositors. No lending of these demand-based funds would be allowed. This holds true for all monetary reform proposals from Soddy to Simons to Fisher to Friedman and to the Kucinich Bill.

But this is a design of the system, taken for reasons of providing stability to this unique group of depositors. It I not a result of a failed design of full-reserve banking. Yes, we plan it that way and hope that will be the result. Is that part a problem?

For the savings/investment funds that would become the ‘backing’ for loans, the sound operation of the bank WILL require a much greater emphasis on maturity-matching, and new ‘bridge’ vehicles for supporting that operational requirement. And, it is true that the market for loans will be the determinant of the return available upon those savings. It would be like a supply-demand-price relationship. Imagine.

But, is that a problem? Does a kinship with S&Ls and Mutual or Cooperative Banking history in some way make full-reserve banking unworkable? Please explain why.

So far, the most you have offered is a caution against the illegality of the profit seekers. We will definitely NOT design the future money system to accommodate illegal greed, Neil. We will be in a unique position to stamp out the ‘illegal’ part. All risk belongs to the bank’s shareholders and its depositors, the latter only being injured by outright fraud. Shareholders who allow errant CEO’s to cross the line of illegality are in the first line of loss. Frankly, this is not something I am worried about in the least. I’m sure that putting somebody almost as smart as Neil Wilson to the task of prosecuting the offenders would be all we need for smooth sailing.

As to whether the money-and-banking inclusive DSGE model satisfies the requirements for where Keen is headed with his model, we shall see. I did not intend to put words in his mouth on its propriety. But in response to a direct question about it, his reply was that his only concern was whether, with all the benefits the CP Revisited modeling produced, would there be enough capital formation to fund the truly innovative projects that might come along. This was immediately addressed as the model produced economic outputs at 10 percent greater than our current money system. Hopefully the videos from the conference will be available soon.

Finally, in that regard, I repeat the conference saw the presentation by Dr. Yamaguchi, whose open-economy, systems-dynamics macro-model Steve Keen opined as the most sophisticated he had ever seen two years ago, came to much the same conclusions as that of the IMF researchers – growth, stability and reduced debt..

So again, your Building Society anecdotes do inform the discussion in terms of the cautions needed to tame our enthusiasm, but that is all they do. I offer you two of the top monetary-economic modelers doing any work in this area, while acknowledging the likeness among full-reserved cooperative banking and Chicago Plan structures.

We are at the point, again, of needing well-informed dialogue here. This has nothing to do with anyone’s faith in anything. I am just trying to openly discuss the substantive differences between MMT and alternative monetary-economic reforms.

Thanks.

“So far, the most you have offered is a caution against the illegality of the profit seekers.”

They are not doing anything illegal. The design is flawed because the lending operation is still separated from the saving operation in time and space. You can exploit the timing differentials there with a large transaction volume to make both sides more liquid that they really should be. And if you can, somebody will.

“All risk belongs to the bank’s shareholders and its depositors,”

No it doesn’t. As I have pointed out, it is fairly straightforward to back fill a loan portfolio by attracting other deposits. That makes the aggressive institution covered and pushes the shortage into the rest of the system where it will cause instability.

It will be the less aggressive institutions that are destroyed – as the consolidation in the Building society sector has demonstrated already. The design structure rewards aggression and boundary pushing.

Banks that lend *must be* entirely separate from transaction executing institutions. Again this follows the old model of the UK industry where building societies did the mortgage lending but didn’t do current accounts, and banks did current accounts but couldn’t do mortgage lending. The prudence of that arrangement is now apparent.

Hicks rejection of IS/LM by Lars P Syll

with background story in a comment from Paul Davidson in a comment!A must read!

http://rwer.wordpress.com/2012/10/04/on-krugmans-reading-list/ and

http://larspsyll.wordpress.com/2012/10/04/hicks-rejection-of-is-lm/