During the recent inflationary episode, the RBA relentlessly pursued the argument that they had to…

Fiscal policy should sustain full employment and reduce inequality

Sometimes there is serendipity in a researcher’s life. Usually not. But sometimes. The last few months I have been investigating the question of how to effectively design fiscal policy interventions. It is an important issue because there are multiple goals that need to be satisfied. Two clear goals can be identified to simplify matters. First, fiscal policy has to be designed and implemented in a way that ensures there is sufficient aggregate demand in the economy relative to its real productive capacity so that full employment is achieved and sustained. Second, it should be designed and implement so as to reduce inequality. The two goals are interdependent despite the myths that economics students learn about the trade-off between efficiency and equity. It is now clear that rising inequality harms the prospects for sustainable economic growth. The evidence is now starting to come in that during the neo-liberal era, fiscal policy was actively used to reduce its redistributive capacity and its capacity to reduce market-generated inequality was severely compromised. Not eliminated but substantially reduced. That is what this blog is about.

Monetary policy has limited capacity to fine-tune distributional impacts because it is such a blunt policy instrument. Interest rate movements clearly impact on fixed-income recipients such that interest rate cuts have a contractionary impact – the income flow is lower for given investment portfolios. This reduces their relative position in the income distribution.

The other major distributional impacts come from the way in which creditors and debtors are affected. An interest rate cut clearly is not beneficial to a creditor but aids a debtor. What is the net effect? It depends, in part, on the saving propensities of each cohort. One might surmise that the creditors have higher saving propensities than debtors because they are lenders. In that case, it might be argued that an interest rate cut thus stimulate a new rise in spending arising from the impacts on creditors and debtors.

But we can conclude that interest rate cuts reduce the relative position of creditors and increase the relative position of debtors. Whether it is a good thing to scale the distributional rewards by the size of the nominal debt held is another matter.

The point I have made previously is that these distributional impacts of monetary policy, while somewhat uncertain, render it an inefficient mechanism for stimulating (or contracting) aggregate demand.

The non-targetting nature of monetary policy makes it inferior to fiscal policy.

But what about the distributional impacts of fiscal policy use? There is a strand of literature that is concerned with that question. Mainstream economists have long taught students (to their detriment) that there is a trade-off between efficiency and equity.

Efficiency, is narrowly defined as putting a “society’s resources to their highest use … [to] … ensure that the economic pie is as large as possible” (IFM working Paper, 08/168 – The Distributional Impact of Fiscal Policy in Honduras).

Allegedly, equity interventions – that are designed to redistribute the economic pie – come at a costs – that is, they reduce the size of the pie. So the policy choice is always constructed as a trade-off, you cannot have one without damaging the other.

The problem is that there is little evidential basis for this assertion. Refer back to my blog yesterday – Republican agenda – simple and venal – where some of the myths about the negative impacts of taxation on growth were challenged.

There is a solid body of evidence that tells us that income inequality and economic growth are negatively related. Rising inequality probably undermines the growth potential of a nation.

Nations that enjoy the longest periods of growth are those that are also moving toward greater equality of income and wealth. The evidence is fairly clear that rising inequality undermines the capacity of nations to grow in sustainable ways.

Even the IMF (April 8, 2011) – Inequality and Unsustainable Growth: Two Sides of the Same Coin? – concluded that:

… longer growth spells are robustly associated with more equality in the income distribution.

A prerequisite for resolving the unsustainable imbalances that led to the financial crisis will be to dramatically redistribute income back to workers – so that real wages growth closely tracks productivity growth and workers in sectors with little union representation are able to similarly participate in national productivity gains.

So fiscal interventions that not only work to ensure there is sufficient aggregate demand to sustain high levels of employment but also aim to dramatically reduce income inequality are both growth-friendly strategies. That is, there is no trade-off of the variety that dominates undergraduate textbooks in economics.

The IMF admit as much in this paper – IFM working Paper, 08/168 – The Distributional Impact of Fiscal Policy in Honduras:

At least for the IMF, the potential tension between equity and efficiency can be avoided by promoting and engendering high-quality growth-that is, “growth that is sustainable in the face of external shocks; accompanied by adequate investment (including in human capital, to lay the basis for future growth); respectful of environmental and national concerns; and, last but not least, consistent with policies that reduce poverty and improve equity” …

While they do not practice what they preach – given they are one of the major promoters of fiscal austerity which undermines equity, erodes the incentives to invest in human capital and provides no room for funding green developmental strategies (just ask what happened to the forests in Mali, for example).

On the theme of fiscal policy and equity, there was an interesting paper in this regard in the IMF Staff Discussion Notes series (No.12/8R) – IMF Income Inequality and Fiscal Policy (2nd Edition) – which was published on September 27, 2012.

The authors provide a detailed account of:

… how fiscal policy can address income inequality in both advanced and developing economies.

They note that fiscal policy can influence the distribution of income:

1. “directly through its effect on current disposable incomes”.

2. “indirectly through its effect on the future earnings capacities-and therefore on market (i.e., pre-tax-and-transfer) incomes-of individuals”.

The authors then move on to examine the trends in income inequality across regions and over time. They conclude that over the last 20 odd years, income inequality has “increased in nearly all advanced and emerging European economies”. Only in Latin America has inequality started to decline since about 2000. Reason? They don’t offer one but the swing to the left of many of the governments there is the likely instigator of this reversal in trend.

The paper notes that:

More recently, the focus has been on the sharp increase in the share of total income of the top income groups. Over the last three decades, the pre-tax-and-transfer income (i.e., market income) shares of the richest have increased substantially in English-speaking advanced economies, as well as in India and China, but much less so in Southern European and Nordic economies, and hardly at all in continental Europe and Japan …

They also note that there does not “appear to be any discernible pattern to changes in income inequality in the aftermath of the financial crisis”. However, there is some evidence that as “fiscal consolidation efforts intensified, inequality started to increase”. Which is consistent with my claim noted above.

The question they then turn to is what has been the role of fiscal policy over this period. The answer is shifting.

They conclude that “(f)iscal policy has played a significant role in reducing income inequality in advanced economies, especially in economies with high initial pre-tax and transfer inequality”:

In every year between 1985 and 2005, fiscal policy (i.e., direct income taxes and transfers) decreased the average Gini in 25 OECD countries by about one-third, that is, by around 15 percentage points …

They document nation-by-nation breakdowns of the extent to which fiscal policy has played a role in reducing income inequality up to 2005.

Significantly, the design of fiscal policy matters:

Most of the redistributive impact of fiscal policy is achieved through the expenditure side of the budget, especially non-means-tested transfers, although income taxes are also important in many economies.

This bears on the current debate where mainstream economists claim that the bulk of the fiscal consolidation that they recommend should be on the expenditure-side with tax cuts being favoured for the rich.

It will be of no surprise that the process works in reverse. If governments attack the expenditure-side (entitlements, transfers etc) and provide further tax breaks to the high income earners they not only will worsen income inequality but also undermine the growth process, both in the short-run as a result of the austerity, but also in the longer-term, by engendering higher inequality.

The final part of the paper I will comment on (due to lack of time) is that the positive redistributive impacts that fiscal policy has been having has been decreasing since the mid-1990s. Over the decade from the mid-1980s:

… fiscal policy offset 73 percent of the 3 percentage-point increase in market income inequality. Although the inequality of market income increased by less over the subsequent decade, the distributive impact of fiscal policy actually diminished. As a result, during the two decades from the mid-1980s to the mid-2000s, fiscal policy offset a much lower 53 percent of this increase, and market income inequality still grew by twice as much as redistribution.

What is the reason for this decline in redistributive impact of fiscal policy?

They culprits line up one after another and they are all called neo-liberal.

The IMF paper says that:

This fall in the redistributive impact of fiscal policy reflected policy reforms that reduced the overall progressivity of the tax-benefit system. In the absence of policy reforms, the distributive impact of progressive tax-benefit systems tends to automatically increase as market income inequality increases (e.g., due to higher unemployment or increasing incomes of higher income groups). However, in many economies, reforms since the mid-1990s have reduced the generosity of social benefits, particularly unemployment and social assistance benefits, and have also reduced income tax rates, especially at higher income levels …

This is the environment that accompanied the labour and financial market deregulation pushes that together created the dynamic where the most destructive characteristics of the capitalist system were unleashed in 2007 and 2008.

The policy developments that undermined the gains in reducing inequality were directly responsible also for the crisis. And what is worse, they are the same policies that are being promoted as a solution to the crisis.

But as the riots all around Southern Europe are starting to tell us – people are no longer believing the lie. The solution that the elites propose to end the crisis – fiscal austerity – will only make it worse. Fiscal austerity is failing and has been failing for some years now. Look at Ireland – it started to destroy itself in early 2009. It is now the end of the 2012. No recovery should take that long and no recovery requires things to get much worse before things get better.

A properly scaled and designed fiscal intervention can not only maintain existing levels of inequality (and reduce it further) but it will also be able to provide for instant employment and income growth. A public sector job offer to an unemployed person is instantly expansionary. The effect is immediate. The same cannot be said for monetary policy interventions.

And now for the serendipitous part of the story …

There was a Sydney Morning Herald article today (November 15, 2012) – To those who have much, more will be given as handouts – which reported on a paper that a Senior Australian Bureau of Statistics official presented to an Economics Meeting yesterday. I have seen the presentation slides.

The SMH article chose to report the controversial aspects of the research and barely put the work the ABS is doing in context. Briefly, there is an OECD-motivated effort underway (since 2010), which national statistical agencies are participating in, that is designed to resolve the anomaly between microeconomic and macroeconomic data published under the System of National Accounts (SNA).

Microeconomic data such as income and expenditure surveys collect detailed information on a unit record basis, which allows us to understand the relationship between income, consumption and wealth and the distribution of each across households.

The National Accounts data – the macroeconomics data provides no distributional perspective and allows us to perceive an “average household”. But, of-course, no particular household might be “average”.

The problem has been that the two sources of data are not consistent. For example, the micro data on consumption does not add up to the National Accounts measure of final household consumption.

In 2009, the OECD Working Party on National Accounts – as the ABS official’s presentation indicated – sought “to create an expert group to devise a robust and internationally comparable methodology that would allow the generation of distributional information on households consistent with the macro (national accounts) estimates”.

From the ABS presentation we read that the goal of the OECD Expert Group that was established is:

To use existing micro data to produce distributional information for household income, consumption and wealth that are consistent with System of National Accounts (SNA) concepts and SNA averages published for the household sector.

The ABS presentation was about the development of that framework and some of the preliminary results that have emerged from the effort to date. I won’t go into the technical aspects of this work although it is very interesting. In due course, when the statistical agencies are satisfied the linking of the micro and macro information is robust enough then a full disclosure will be forthcoming. Then we can return to examine the work.

But as a result of the preliminary work to date there have been some very interesting results emerging. It was these results that the SMH article reported on.

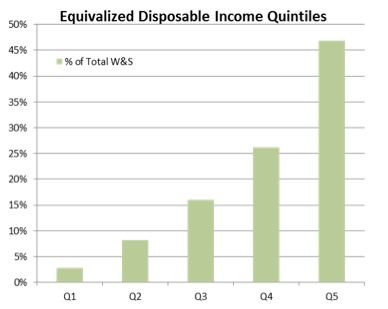

The ABS presentation produced the following graph f0r 2009-10, which shows the distribution of wage and salary income across the income quintiles in Australia. What you observe is that the top 20 per cent of Australian household income recipients take about 46 per cent of the total wages and salaries paid out. The bottom quintile earn less than 3 per cent of the total wages and salaries paid in Australia.

So there is considerable wage inequity in Australia.

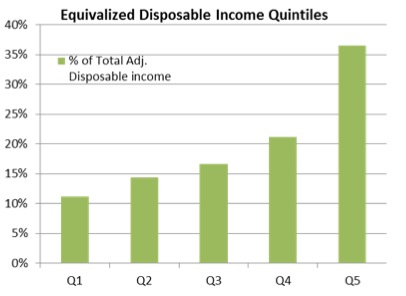

But there is more to this story. Once the so-called “redistributive” function of government policy impacts – so the “cash payments and social transfers in kind (such as public education and healthcare) are taken into account”, the following graph is produced.

It shows that the top income quintile now receives 36 per cent while the lowest quintiles share rises to 11 per cent. So considerable inequality remains after the redistributive system takes place.

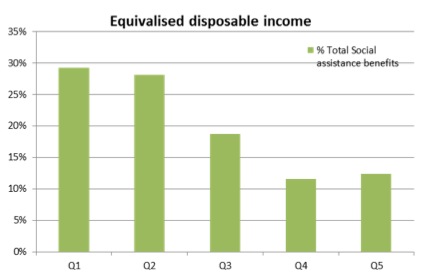

Then the really stunning result emerged. The ABS presented a distributional breakdown of the total social assistance benefits provided by government. The following graph summarises the result.

The two bottom income-earning quintiles get close to 28 per cent of the total social assistance benefits each – so just over a half. But check out the top quintile. It gets 12 per cent of total social assistance benefits closely followed by the fourth quintile (Q4) which gets around 11 per cent of the total benefits paid out by government.

You might like to ask why government social transfers are being handed out to the highest income-recipients in our nation? Answer: welfare for the rich to supplement the corporate welfare that the so-called more efficient private sector relies on from government.

The Australian social benefits system is thus very poorly targetted – the SMH article notes that many “high-income households qualify for the childcare rebate, which is not means tested, and the private health insurance rebate”.

Australia has followed the trend noted above and cut into the redistributive elements of fiscal policy, which had maintained our levels of inequality well below many comparable nations (especially in the Anglo world). But inequality in Australia has been rising and one of the major reasons has been the labour market deregulation brought in by the federal government, the legislative attacks on the trade union movement; and the tightening of social transfers.

That trend represents another dimension in the way that fiscal policy has been misused in Australia and will undermine our future prosperity.

Conclusion

The neo-liberal era has seen mainstream economists eschew the use of fiscal policy in favour of monetary policy and the result has been persistently higher unemployment than should have been the case.

But within that antagonism for fiscal policy, it is clear that the redistributive characteristics of fiscal policy – which were designed to reduce inequalities – have been undermined and various policy changes have seen a new fiscal approach in favour of the rich. A total perversion of what should be happening.

If you examine the various approaches to fiscal consolidation that are being pursued at present you will detect that that this trend is being continued. The major attacks on public spending will hurt the poor and not the rich.

Upcoming CofFEE Workshop

I am hosting a workshop next Tuesday at the Charles Darwin University, Darwin on Timor. The details are as follows if anyone is interested in coming up to the Top-End and having some fun with us.

The aim of the workshop is to start addressing the World Bank/IMF bias in the economic policy debates about how Timor-Leste might better develop and solve its shocking unemployment problem.

The Workshop will be held on Tuesday, November 20, 2012 from 13:00 to 17:00. The location is the Red Room, Northern Institute, Yellow Building 1, first floor.

The Program will be:

13:00 Introduction and Welcome – Professor Bill Mitchell, CofFEE Director

13:10-14:00 Dr Daniel Kostzer, Senior Economist with the UN Secretariat in Timor-Leste.

Daniel has worked with the UNDP for some years in Argentina as the Coordinator of the Social Development Cluster. Both programmes help reduce poverty and to encourage the economic growth of these nations. He has published widely in all his areas of study, but in recent years his research has focused on Timor-Leste specific issues such as the impact of the United Nations Integrated Mission in Timor-Leste (UNMIT) in the local economy, producing a Geographic Index of Social Vulnerability, and developing a macroeconomic framework for the 2012 State Budget in Timor-Leste.

He is a Professor of Income Distribution and Poverty Reduction, Masters of Labour Economics for Development (MALED) for the ILO (Turin), University of Turin and University of Paris. He is also a Professor of New Development of Public Policies, Masters of Labor Relations at the University of Bologna, Buenos Aires.

Daniel previously worked within the Argentinean government in various roles including both Senior Economic Advisor and the Director of Research and Macroeconomic Coordination in the Ministry of Labour Employment and Social Security during the restorative years in the early 2000’s and was instrumental in the creation of the Jefes de Hogar Desempleados (Unemployed Head of Households) plan that saw the implementation of a restricted Job Guarantee scheme for the Argentinean people.

Topic: The socio-economic structure of the first republic of the 21st Century: Timor-Leste.

13:40-14:40 Avelino Maria Coelho da Silva, Secretary of State for the Council of Ministers, Government of the Democratic Republic of Timor Leste

Topic: Evaluating the economic and employment progress of Timor Leste and a proposal for co-operative self-sufficient agricultural development.

14:40-15:00 – Afternoon Tea

15:00-15:40 – Martin Hardie, Lecturer in Law, Deakin University, former solicitor, barrister and advisor to the East Timorese resistance and government

Topic: Personal reflections on the role of the UNTAET in setting the economic fundamentals of the East Timorese economy.

15:40-16:20 – Professor Bill Mitchell

Topic: Currency sovereignty and the need for employment guarantees in developing nations.

16:20-17:00 – Panel Discussion

I hope to be able to live stream the Workshop for those abroad who cannot easily get down here. More details about this will be posted once I work out whether it is possible from the location we are using.

That is enough for today!

“The Australian social benefits system is thus very poorly targeted – the SMH article notes that many “high-income households qualify for the childcare rebate, which is not means tested, and the private health insurance rebate””

Poorly targeted?! This is shocking. Do you say that rich should not receive childcare only because they are rich but poor should only because they are poor?! Do you say that rich should pay for public schools and poor should not? Do you say that rich should pay for roads, police, air and so on but poor should not? There are other dimensions of human life and society than just money and monetary equality.

I am really shocked.

Bill. UK equivalent from ONS.

http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171778_267839.pdf

Dear Bill

As I see it, lower interest rates will induce people to save more because so much saving is target saving, that is, the saver aims to accumulate a certain amount. Suppose that Peter wants to have 500,000 dollars (with today’s purchasing power) available when he turns 65. Then he obviously has to save a higer percentage of his income when the real interest rate is 2% than when it is 5%.

There is not only vertical equity but also horizontal equity. If a couple with an income of 100,000 and 2 young children pays less tax than a childless couple with an income of 100,000, then this is quite acceptable in my opinion. If a perfectly healthy bachelor pays more tax than a severely ill bachelor with the same income, then that seems just to me.

Regards. James

Bill,

I’m always impressed that you can bring yourself to read report after report from the IMF.

Whenever George Osborne comes on the news and starts talking nonsense about dealing with the deficit I shout at the telly for two minutes then have to change channel. But then I guess you are occasionally rewarded by the IMF with a nugget or two of unwitting hypocrisy. Must make it all worth it!

@Acorn thanks for posting the UK ONS data. Interesting to see the Gini graph towards the end – shame they didn’t extend the chart back earlier than 1977!

Andi

If benefits are means-tested they are seen as poor-aid ie. aid to the poor who are too lazy or incompetent to support themselfs and their families. Support for this kind of aid is limited.

Whereas if benefits are universals they are tought as “belonging to the people”. Much more support.

I think a shortcoming of MMT with respect to problem solving, is the lack of distinction within the private sector between financial sector assets and productive sector assets where jobs are created. The economy stalls because of financial mal-investment (often by over-taxing the productive sector with debt). Lowering government taxes on business seldom has a supply-side beneficial effect because production is demand driven. With lower government taxes, the shadow taxation of the financial sector can increase the unearned transfer of assets and revenue while maintaining marginal national growth (the euro project as a wealth transfer business).

The paradox of thrift is more a function of mal-investment of savings (rent-seeking) rather than having a direct negative impact on consumption (Nicholas Johannsen). A tax on wealth inequality reduces the mal-investment impact of rent-seeking with dark pools of money. Labor cuts it’s own throat because those dark pools frequently consist pension money and other privatized “savings” vehicles for the middle-class. This argues against privatizing social security as well as privatizing pensions in general and pursuit of unearned income. I think that the financial sector, banks, contributed less than 1.5% of GDP in 1910. Wealth was invested in the productive sector (Roaring 20’s) which ultimately had a negative impact via consolidations and ultimate ownership of production by financial types with different objectives (rent-seeking rather than production or service efficiency) (Louis Brandeis). The first sign of ownership neglect were lapses in safety, which we continue to see today in healthcare.

Bill, have you seen this discussion of bank misbehaviour.

It would be interesting to hear the MMT take on this.

this further convinces me that the fiscal stimulus should be directly targeted at income in a progressive

manor

welfare for the 75% as it were

a living wage for lower 50% tapering of to zero at 75th centile of population income

less logistically difficult and centralist than the job guarantee

to win the political battle decoupled from bond issue

to win the “scrounger debate” when 75% of population are welfare recipients

increasing the spending power of the majority is the best path to growth jobs and a healthy work life balance

“a living wage for lower 50% tapering of to zero at 75th centile of population income”

That’s what tax credits are supposed to do. But it falls down.

You can’t have a wage if systemically there simply aren’t enough jobs.

The marginal rate of tax exceeds 70% in the mid range – which is into discincentive territory.

For a work = income = resources distribution model to function, there has to be enough work for all paying sufficient income to avoid poverty. It’s as simple as that.

Or you change the distribution model completely and break the link with work.

my point of an income guarantee

is to brake the chronic entrenched lack of demand

tp provide the most effective fiscal stimulus

spending = income

the amount and breadth of income provided by the currency issuer should be contingent on

delivering a full voluntary employment outcome through increased spending by directly supplementing

the spending power of the majority

i am not against the state employing more people

working in the nhs we could do with more staff

education services no doubt feel the same

I doubt that private investment in energy supply will keep the lights on in the uk

in the near future

mass transportation could be more effective socialized backed by the currency issuer

but for what’s left of the private sector in a mixed economy

I think an income supplement would be less buerocratic and centralist than a job guarantee

and more effective as it’s scope would be broader

it will still leave the problem of super profiteering and asset price inflation

“I think an income supplement would be less buerocratic and centralist than a job guarantee”

And how do you stop the drift towards not doing anything? You can’t give income to people without them promising to do something in return or you start generating resentment and a loss of production. The state has to have the ability to organise necessary production should the private sector really goes into full failure mode.

Job Guarantee has nothing to do with centralisation. Where this idea comes from I have absolutely no idea. In Job Guarantee the state pays the wages of those who have worked but not been paid. In the UK that can be handled via the Real Time Info system behind PAYE. If an employer files a payslip with hours but no pay, then the state pays the living wage for those hours.

The debate then is which employers will be allowed to do that and what supplemental mechanisms need to be in place to make sure that enough jobs are organised. That may involve supplemental grants to local councils or voluntary organisations, or the creation of new employer organisations. All the MMT literature states this needs to be heavily distributed so that local labour can be directed towards the local public purpose.

I do not subscribe to the voluntary unemployed position

but maybe with an income provided by the currency issuer some people would not choose to

work as many hours as they do now

I think people want a healthy life work balance and would not except a basic living wage

but would seek out work opportunities to add to their prosperity

it is crucial to avoid resentment

these payments should not be funded by taxes or bond issue

maybe 75 % of population is not broad enough maybe a slower fade out to 90% of pop

as I said I think government should employ more people

and undoubtably the locally organized job guarantee you describe is a vast improvement

on current government policies

but I do not think such fiscal stimulus would go far enough

to address the inequalities which bill blogs about here

I meant centrist in the sense that the government needs to be the backstop for

employment in the private sector

by giving a living income to all and progressively reducing this for the vast majority

the private sector will get all the signals it requires to provide enough jobs

for those the government does not want to employ

funded should have the required bunny ears “funded” accounted for

You can’t give income to people without them promising to do something in return or you start generating resentment and a loss of production. Neil Wilson

1) The entire population deserves restitution since credit creation cheats both debtors (by driving them into debt) and non-debtors (negative real interest rates on their savings).

2) The economy already has excessive productive capacity and that capacity was often built with the stolen purchasing power of the entire population. The population thus deserves a “Social Dividend” for their involuntary investment.

3) Idleness is often a result of not owning land to work on and improve; land they or their ancestors were driven off of by the banks.

4) Paying people to waste time is far worse them simply giving them money. Thus if there is insufficient useful infrastructure work to be done then a shortfall in aggregate demand should be made up by simply giving the population money and letting them find their own useful work to do. This would drive up the pay and working conditions of workers too since poverty would no longer force them to work for a living. It would also drive up the quality of the workforce since the workers would be willing. Note that the same effect, willing workers, would have been the result of ethical money creation since it is likely that the workers would have received a fair share in the profits of businesses instead of being exploited. We could have been spared many labor disputes and Communism if we had had ethical money creation.

5) If we are unwilling to let people starve, be naked, or go homeless (and we should be) then a minimum income, with or without work, is required anyway. Why not save ourselves the adminstrative expense then and just give people money? And if we don’t want idle people roaming around causing mischief then let’s bring back the family farm so they at least have an opportunity to occupy themselves usefully.

We have created an unjust society in the name of “efficency.” But how efficent is a society that has enormous social and political costs becuase that “efficency” was obtained unjustly? Indeed the Bible anticipates this result:

He who increases his wealth by interest and usury

gathers it for him who is gracious to the poor. Provertbs 28:8 NASB

the title of this blog is fiscal policy should sustain full employment and address inequality

what is the best way to achieve this?

once we accept the central concept of MMT that the government the currency issuer is not fiscally constrained

many possibilities follow

what questions should guide us

1 how much currency should. be issued?

2 to whom?

3 to what purpose?

if the answer to 3 is the title of the blog it seems to me the best way to achieve this

is to progressively supplement the income of citizens

the evils of usury are the consequence of need

the benefits of privately issued debt with it’s future liabilities is increased productive capacity

of course the possibility of demand pull inflation is real

but the spending choices of the recipients of currency issue cannot and should not be controlled

sectors which historically have delivered inflation could be targeted

rent controls mortgage controls govt provision of housing

govt provision of energy

of course when full voluntary employment is achieved the levels of supplement could be reduced

when we dispense with the crystal ball the preferred tool of mainstream economics

we should let the facts dictate the level of fiscal stimulus guided by egalitarianism in it’s distribution