It’s Wednesday and I just finished a ‘Conversation’ with the Economics Society of Australia, where I talked about Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and its application to current policy issues. Some of the questions were excellent and challenging to answer, which is the best way. You can view an edited version of the discussion below and…

Keynes and the Classics – Part 2

I am departing from regular practice today by taking advantage of a lull in the news reports to advance the draft versions of the Modern Monetary Theory textbook that I am writing with my colleague and friend Randy Wray. We are behind schedule at present and so I am concentrating attention on progressing the project to completion. I am also currently avoiding any commentary about the US fiscal cliff resolution farce – I thought Andy Borowitz (January 3, 2012) –

Washington celebrates solving totally unnecessary crisis they created – was about right. Hysterical if it wasn’t so tragic. America – we are all laughing at you – while laughing at our own stupidity as well given the behaviour of our own governments (Europe, UK, Australia etc). Anyway, comments are always welcome. Remember this is a textbook aimed at undergraduate students and so the writing will be different from my usual blog free-for-all. Note also that the text I post is just the work I am doing by way of the first draft so the material posted will not represent the complete text. Further it will change once the two of us have edited it.

I am currently working on Chapter 11 which opens like this:

Chapter 11

11.1 Introduction and Aims

In Chapter 10, we discussed issues relating to labour market measurement. In this Chapter we will focus on theoretical concepts that underpin the measurement of economic activity in the labour market and the broader economy.

The Chapter has five main aims:

- To explain why mass unemployment arises and how it can be resolved.

- To develop the concept of full employment.

- To consider the relationship between unemployment and inflation – the so-called Phillips Curve.

- To develop a buffer stock framework for macroeconomic management (full employment and price stability) and compare and contrast the use of unemployment and employment as buffer stocks in this context.

- To more fully explore the concept of a Job Guarantee (employment buffer stock) approach to macroeconomic management.

NOTE:

At present, I am outlining the Classical theory of employment determination and output – which is the basis of their denial of involuntary unemployment. In the section last week – Keynes and the Classics – Part 1 – I explained how the Classical system conceives of labour supply and demand and how these come together to define the equilibrium level of the real wage and employment.

This equilibrium defines the Classical concept of full employment.

Today, we see how unemployment can occur in this model and also explain how the theory of employment leads to a theory of aggregate supply. Then we consider why aggregate demand can never be deficient in this system.

NEW TEXT STARTS TODAY

11.7 Unemployment in the Classical Labour Market

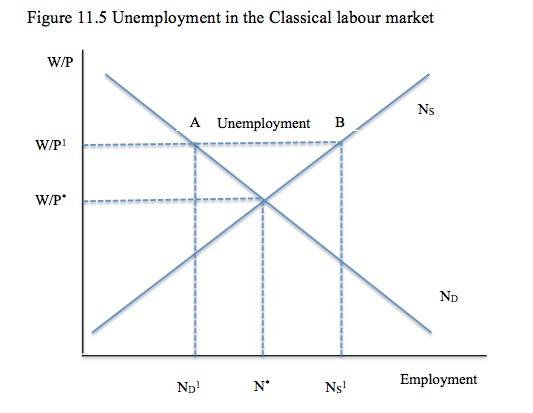

Imagine that for some reason, the real wage was at (W/P)1. We show this in Figure 11.5. This is a departure from the current equilibrium at W/P*, N*.

Workers are attracted by the higher real wage and are prepared to offer more hours of work (Ns1) because the price of leisure has risen and so they substitute away from the relatively more expensive good.

Firms, however, reduce their demand for labour (ND1) in order to seek a higher marginal product of labour.

The general rule is that the “short-side” of the market is dominant in disequilibrium situations, which in this case means that total employment would be at A while the labour supply would be at B. The difference (B – A) measures the excess supply of labour at W/P1 or unemployment.

So unemployment can only arise in the Classical system if the real wage is above the equilibrium real wage. From a macroeconomic perspective, the Classical theory of employment denied the existence of involuntary unemployment.

You might argue that the government minimum wage legislation was not the choice of the workers and so in that sense, the unemployment that the Classical system generates from an excessive minimum wage would not be voluntary. The response would be that the workers could normally place political pressure on the government to reduce or scrap the minimum wage – the ultimate pressure being to vote them out of office.

For the Classical economists of the 1930s, this state would be temporary unless there were institutional rigidities, which prevented the real wage from falling. Why?

They believed that if the labour market was left to adjust on its own accord, the excess supply of labour would start to drive the price down until the labour market equilibrated at the equilibrium at W/P*, N*.

In that sense, the unemployment (B – A) would be considered temporary.

There was recognition that institutional forces could prolong that adjustment. For example, trade unions might prevent the real wage from falling back to the equilibrium value at W/P*. In this case, the unemployment would be considered voluntary because workers could choose to refuse union membership and offer themselves at the lower wages outside of any wage floors the union might try to enforce.

Another often-used example is the imposition of a minimum wage by the government, which might force the real wage to be higher than the equilibrium real wage. The solution to the unemployment in that case is for the government to eliminate the minimum wage and allow the equilibrium real wage W/P* to reassert itself.

In other words, unemployment could not exist in the Classical employment theory if real wages were flexible in both directions and were allowed to adjust to balance the forces of supply and demand.

It goes without saying that a real wage below the equilibrium W/P* would result in an excess demand for labour, which would force the real wage to rise back to W/P*, thus eliminating any imbalance.

By way of summary, the Classical theory of employment argues that:

- The Labour Supply function represents the preferences of workers between work (a bad) and leisure (a good), while the labour demand function is determined by the current state of technology (which determines labour productivity).

- Profit maximising firms set the real wage equal to the marginal product, which determines how much labour they are prepared to employ. The real wage is also the opportunity cost of leisure for the worker, and when the real wage rises (falls) the workers supply more (less) labour.

- The interaction between the labour demand and supply functions determines the equilibrium real wage and employment level in each period.

- rm) is thus a technological mapping from the equilibrium employment determined by the equilibrium relationship into the production function.

- The existence of unemployment is due to the real wage being above the equilibrium real wage that would be established by the intersection of labour demand and labour supply.

- Real wage flexibility would ensure that such unemployment was of a temporary nature.

- Changes in the preferences of the workers towards work (which shift the labour supply curve in or out) and/or changes in technology which sift the labour demand curve (in or out) change the equilibrium real wage and employment level. As a consequence, these changes would lead to a change in the level of employment that was considered to constitute full employment. Given real wage flexibility, departures from full employment are ephemeral at best. Any sustained unemployment must be due to a real wage constraint imposed on the market.

11.8 What is the equilibrium output level?

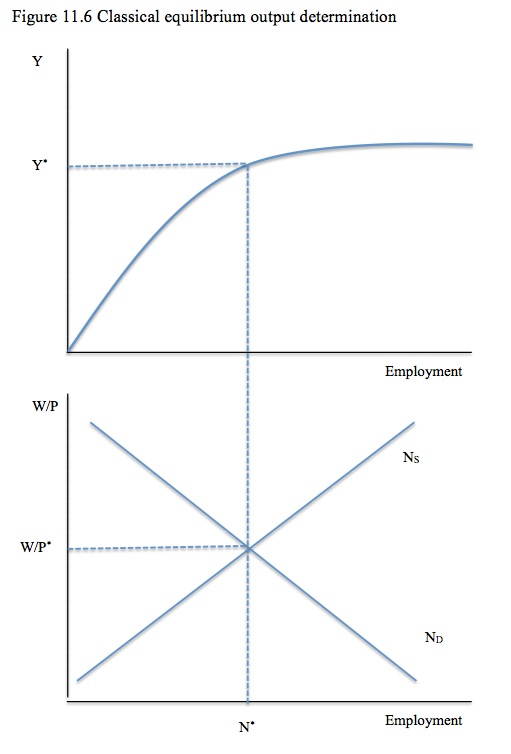

It should be clear from the previous analysis that the level of employment and the real wage is determined in the labour market within the Classical system.

In turn, once the equilibrium level of employment is determined, the equilibrium level of output (real GDP) is also determined given the available technology. The latter determines the shape and position of the production function.

Figure 11.6 brings together the Classical labour market and the production function. You can see that the equilibrium level of employment generates a particular output level (Y*) which then constitutes the aggregate supply for the economy.

The next question we have to ask is: What guarantees that the flow of real GDP produced (Y*) will be sold each period?

In other words, why is this an equilibrium level of real output?

What did the Classical system invoke to ensure that the labour market equilibrium with no excess supply or demand, would be consistent with a product market equilibrium where aggregate demand for goods and services was equal to aggregate supply (Y*)?

The answer is that they developed the loanable funds theory, which ensures that saving and investment are always equal.

11.9 The loanable funds market – eliminating the possibility of an aggregate demand deficiency

The Classical theory adopted the view that there could be no general deficiency in planned aggregate spending, which would leave total productive capacity idle.

They admitted that specific goods and services could be “over-produced” but believed that rapid market adjustments would ensure there could never be a generalised glut or ever occur.

The denial that generalised over-production could occur has become known as “Say’s Law” after the French economist Jean-Baptiste Say, who popularised the view.

The idea is sometimes summarised by the epithet – “supply creates its own demand”. The logic is that by supplying goods and services into the market, beyond the output intended for own-use consumption, producers are signalling a desire to exchange their surplus output for other goods supplied into the market.

In other words, everything that is supplied is simultaneously a desire to demand (for own-use or for exchange).

Using the terminology developed in Chapter 9, and assuming for simplicity a closed economy without a government sector, which is the typical depiction of the Classical system, we know that the total flow of spending in the economy is in equilibrium equal to total real GDP and national income (Y).

Total spending is the sum of consumption (C) and investment (I):

(11.6) Y = C + I

Equilibrium requires that real output (Y) is sold each period.

National income is either consumed (C) or saved (S) which allows us to write:

(11.7) Y = C + S

In equilibrium:

(11.8) C + I = C + S

Which means that the equilibrium condition is S = I, or planned saving is equal to planned investment. This means that all goods designed to be consumed are sold and the remaining national income is equal to investment (designed to provide for future consumption).

So the Classical system allowed for a desire to save in any period, but argued that the withheld consumption would be matched by (planned) investment spending given that the saving was just a signal that consumers wanted to consume in the future.

From an existing equilibrium, imagine that the desire to save rose. Consumption would fall in the current period and to maintain the equilibrium output level planned investment would have to rise.

What mechanism exists that would bring planned saving and planned investment into equality each period to allow for shifts in, for example, consumer behaviour (a rise in the desire to save in this case)?

Ignoring questions relating to the logistics of how an economy might quickly shift between the production of consumption and investment goods, the answer lay in the way the loanable funds market operated.

The theory of loanable funds provided the Classical system with the vehicle to explain how aggregate demand could never fall short of aggregate supply. The continuous equilibration would be achieved by interest rate adjustments, which would always bring planned saving and planned investment into equality as household and firms preferences changed.

The loanable funds market is really a primitive depiction of a financial system.

Savers (lenders) enter the market to see a return on their savings to enhance the future consumption possibilities. Equally, firms seeking to invest (borrowers) enter the loanable funds market to get loans.

The interest rate that is determined in this market provides the return to households for their saving and determines the cost of borrowing funds for investment.

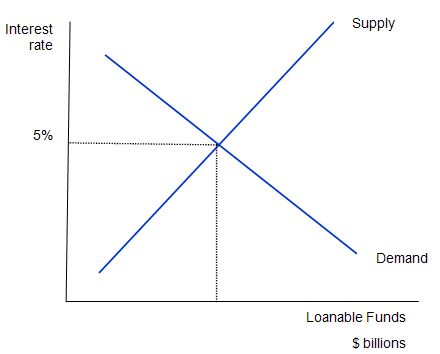

The following diagram shows the market for loanable funds. The supply of funds comes from those people who have some extra income that they want to save and lend out. As the interest rate rises, the return on saving rises and so the supply of funds (saving) rises.

The demand for funds comes from borrowers who wish to invest in houses, factories, and equipment among other productive projects. As the cost of borrowing (the interest rate) rises, the demand for funds falls because the net return on the planned projects diminishes.

The interest rate adjusts to ensure the supply of funds (saving) equals the demand for loans (investment). In Figure 11.7, the equilibrium interest rate is 5 per cent.

[NOTE: We will render this rate i* in the final text to generalise it and change the text accordingly]

If the interest rate was below the equilibrium rate then the volume of funds demanded from the loanable funds market by would be borrowers would exceed the supply of loanable funds and competition among the borrowers would force the interest rate up. As the interest rate rises, planned saving would increase and planned investment would decline. At the equilibrium interest rate, the imbalance between supply and demand would be eliminated and planned saving would equal planned investment.

The converse then follows if the interest rate is above the equilibrium.

Figure 11.7 Loanable funds equilibrium

[TO BE CONTINUED …]

Conclusion

Tomorrow, I will continue with this Chapter unless something explosive happens overnight.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

It’s probably some failing on my part, but I can never understand how “loanable funds” can be reconciled with the “money multiplier”.

@Bill

Could you look at the Euro trick card they keep playing.

Wage deflation in the core which they seem to use to free up surplus capital to inflate more primitive jurisdictions , creating a sort of giant series of onion rings.

It started in the 60s & 70s – we got some shipbuilding from Holland into Cork during that time before they carted off to Asia.

OK we did the Spain thingy ……whats next ?

Morocco here we come……………

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CEKHG8uvjXk

Anybody see a general pattern here ?

Give them modern toys in exchange for debt……..

When the country has lost all redundancy you pull the rug from under it.

Its the Ceausescu gambit played over and over again.

This is where Irish “austerity” is ending up.

Its money without a political input.

So therefore we don’t use money.

We use capital tokens.

The $ post 1922 was the first modern global (petro) currency.

The Euro is their perfected abomination.

Ask yourself why the core snake of the 70s did the wage deflation thingy………so that it could export oil inflation elsewhere…..i.e. to Ireland , Spain etc.

These societies are now completely destroyed……….its time to move on to greener pastures.

The dangers of now fully privatized money is seen all around us.

Spain is collapsing simply because it cannot produce any national tokens to use its previous massive investments.

Now France is leaving its southern neighbour which it shares a very long border with to rot in a debt stew while it engages in a manic effort to sell stuff to its former colonies in Africa…………

Industrial co-localization…………..I like that.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B7ezP4K3oF4

It produces nothing net.

Its more labour extraction of value.

The Euro is a expression of pure evil.

The wastage of present intact resources to build more junk is simply fantastic.

Because the Euro is a capital tokens rather then a money token it must build more and more stuff.

It is much like a Shark – it must keep swimming and hunting.

If not it becomes organic rain for the various bottom feeders.

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/6d/PSM_V23_D086_The_deep_sea_fish_eurypharynx_pelecanoides.jpg

@Bill ~ If you haven’t caught this yet, you’ll want to. From FT/Alphaville, On the new purpose of government debt.

The BIS apparently just figured this out?

The FT Alphaville piece is a brief comment on a post by Frances Coppola, a professional singer and teacher who used to work in banking and finance. The post is worth reading, including the comments by umabird and Coppola’s responses. In saying this, I am not suggesting agreement with what she writes.

http://coppolacomment.blogspot.co.uk/2013/01/when-governments-become-banks.html

A more recent post is ‘Slaying the Inflation Monster’.

Frances Coppola, in her newest blog post brought my attention to a recent paper from the Bank of International Settlements (BIS), which is pertinent to many points Bill has made over the many months his blog has been operating.

I down loaded the paper from:

http://www.bis.org/publ/work399.pdf

The following statement stood out:

” Gary Gorton, in response to the failure of private sector “safe” assets, remarked that only governments can create “safe” assets. But not all governments can. The Eurozone crisis shows us that those that don’t issue their own currency, those that are perceived by markets as being profligate, and those that are suffering severe political or economic stresses – none of these can produce “safe” assets. There is a diminishing number of countries that can produce assets that are reliably regarded as “safe”, while global demand for safe assets is skyrocketing due to increased regulatory requirements for financial institutions, shortening collateral chains in shadow banking, and investor risk aversion.

There have been numerous attempts to explain the declining yields on US, UK and Japanese debt, since in all three of these the debt/GDP ratio is considerable and rising, which should force their yields up. Pessimistic commentors have been warning for years that these debt assets are overvalued and collapse is imminent, but there is still no sign of this. The US downgrade is now a year old and yet US Treasuries are trading at the lowest yields in history. The UK faces probable downgrade in the spring, but the markets don’t seem to care. And the most inexplicable of the lot is Japan, which has the highest debt/GDP ratio in the world but pays the lowest borrowing costs. Markets really don’t seem that bothered about high debt/GDP ratios in these countries. It seems grossly unfair that a country such as Italy, which in economic fundamentals is rather similar to the UK, pays much more to borrow. But the difference is that Italy has no central bank. Yes, I know it has something CALLED a central bank – but it is part of the Eurosystem and subject to the ECB’s rules. It cannot issue currency except with the ECB’s permission and has no control of monetary policy.

The BIS paper makes it very clear that a country that has no central bank, does not issue its own currency and has no control of monetary policy cannot create “safe” assets. The crucial determinant of markets’ attitude to debt is the existence of a credible monetary backstop. BIS recommends that central banks should act as investor of last resort for their own countries’ debt – monetizing freely on demand. This is not to shore up government finances (I shall return to this in a minute), nor to adjust monetary policy. No, it is to instil confidence in the debt. If investors know that the central bank will always exchange government debt for money, they can regard that debt as 100% safe.”

INDY

Dr. Prof. Mitchell,

Would it be accurate to say, based on this chapter, that what the loanable funds theory does is to add another excess demand (the money excess demand!) to the Say/Walras identity?

In algebraic terms:

Say/Walras

sum(P[i]*(D[i]-S[i]), i, 1..n) = 0

Loanable funds:

sum(P[i]*(D[i]-S[i]), i, 1..n) + I*(MD-MS) = 0

(there are n goods, indexed by i; P[i], D[i] and S[i] are the price, quantity demanded and supplied of good i; I is the interest rate and MD and MS are demand and supply of money)

Graphically, we have n supply/demand figures similar to 11.7 (but referring to goods) for the Walras/Say. With the loanable funds theory we add figure 11.7.