It's Wednesday and I discuss a number of topics today. First, the 'million simulations' that…

Not even remotely correct

There has been a bit of fun in the last week, with the IMF accusing our previous conservative government (10 increasing surpluses out of 11 years in power – 1996-2007) of being the only period of profligate fiscal policy over the last 50 years. That is hysterical really because the government in question held themselves out as the exemplars of fiscal prudence and responsibility. They were, in fact, one of the most irresponsible managers of macroeconomic policy in our history, but not for the reasons that the IMF would identify. All this shows how far fetched the research that the IMF is spending millions of public dollars (donated by member governments) has become. One week they are admitting how wrong their forecasts are with millions losing their jobs as a result and the next week they are handing out medals for fiscal prudence and backhanders for wasteful spending. I was going to analyse the underlying IMF paper today because it is illustrative of why the IMF keeps making these fundamental errors. But I was sidetracked and got lost in some data and some other things. So the IMF tomorrow (maybe) and today a little walk through some trends which confirm why the IMF has a problem recruiting good economists. It all starts with their miseducation in our universities. The point is a casual look at the data shows that the mainstream of my profession hasn’t been even remotely correct in its statements over the last 4-5 years.

There was also an interesting paper published last year (September 24, 2012) – The Financial Crisis and Inflation Expectations – by the US Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, which explored attitudes to inflation in the US and the UK.

The paper points out the obvious:

A major financial crisis, such as that of 2008-09, can be considered a natural test of this anchoring … [of inflation expectations] …

We are now 4 years or so into the crisis and the rather (relatively) large fiscal and monetary policy shifts that were introduced back in 2008 and have not yet been reversed in many advanced nations – especially the monetary policy shifts. The central bank balance sheets are still in “non standard” monetary policy shape.

Each year that followed there were predictions of doom. Nothing happened to substantiate the predictions. The retort was that it is too early. Once growth returns, or once expectations adjust, or once upon a time … the sky would fall in.

Another year passed, the sky remained in place. Just wait, the crash is coming. Ok.

Another year, and so on.

If we asked a senior undergraduate macroeconomic class at a mainstream university or a post-graduate class what they thought was going to happen in 2008 (by NOW) based upon what they had been subjected to by way of macroeconomic theory they would tell us more or less the following. The post-grads would use fancier language reflecting the increased sophistication of the technical apparatus the lecturers use to obfuscate the reality. But the answers would be similar.

1. Interest rates would rise because the deficits had risen.

2. Inflation would rise because of the massive increase in the monetary base, which would lead (via the mythical money multiplier) to

3. Treasury bond auctions would fail as the bid-to-cover ratio fell, reflecting the increasing lack of confidence that private investors had in the solvency of the governments. Treasury bond prices would fall as a consequence.

4. There would be no increase in real GDP growth because the non-government sector would move to offset the rise in public spending. Why? The private households and firms would form the view that the rising deficits would have to be paid back via tax rises sometime soon and so they would have to start saving now (withdrawing spending) to ensure they could meet the future tax rises.

5. Public spending multipliers would thus be well below one, meaning that for every dollar spent by the government, the economy would grow in nominal terms by less than a dollar – the more extreme predictions would say be much less even suggesting a contraction of some magnitude (more than total crowding out).

6. Where nations imposed fiscal austerity, the students would have predicted that the economies would have grown faster as a result of the reverse logic pertaining to all the above points.

All these basic predictions of mainstream macroeconomic theory have not eventuated. In fact, the reverse has been happened. Various strands of evidence would tell us that. Even some of the arch proponents of all these predictions – the IMF – have admitted they made terrible mistakes with respect to their predictions (especially in relation to points 4, 5 and 6).

It is a pity that millions of ordinary folk – not those working in Washington on high pay – have become unemployed and lost their savings as a result of the IMF incompetence.

It is clear that these forecasters haven’t understood modern history – say from 1990 onwards. Even without knowing much about the way the economy operated a relatively intelligent person – that is, one who can get out of bed each morning and navigate a car or find the right bus number to reach a destination would be able to conclude that the data from say, Japan totally negated the view held by mainstream macroeconomists.

Perhaps all the doom and gloom merchants from the US don’t actually read world news. I might have mentioned this before but I recall hearing an interview on the ABC (Australia’s national public broadcaster) with a US academic who was about to visit Australia for a conference (it was the middle of May by the way – which is important to avoid any misinterpretations relating to international date lines).

At the end of the interview, he was being friendly and said “By the way, what month is is down there?”. Hilarious.

Which reminded me of a time I was in San Francisco – at the height of the – Bosnian Genocide – at Srebrenica and Zepa in 1995. A major world event by any standards which received front page coverage in most of the World’s newspapers. On the day the information seeped out to the world, the largest daily in San Francisco covered a front page headline story like “cat rescued from tree by police officer in Oakland” and the massacre was a small column on page 5 or something.

While on the theme of having fun, here is a couple of minutes of amusement from Break.Com.

Apparently, that is not fair because the US is a big important place and people are more interested in domestic issues. Okay, a couple of years ago, the Newsweek Magazine gave 1000 Americans the official US Citizenship Test – “29 percent couldn’t name the vice president”.

According to this summary (May 20, 2011) – How Dumb Are We?:

Seventy-three percent couldn’t correctly say why we fought the Cold War. Forty-four percent were unable to define the Bill of Rights. And 6 percent couldn’t even circle Independence Day on a calendar.

It seems though that intelligent Americans know their second amendment – at least I have heard gun owners talking about that a bit lately.

Previous research shows that only “58 percent of Americans” quizzed could say who the Taliban were, despite the US leading “the charge in Afghanistan”.

And the ignorance appears to spill over into matters relating to the federal budget. As the article – How Dumb Are We? reports:

… poll after poll shows that voters have no clue what the budget actually looks like. A 2010 World Public Opinion survey found that Americans want to tackle deficits by cutting foreign aid from what they believe is the current level (27 percent of the budget) to a more prudent 13 percent. The real number is under 1 percent. A Jan. 25 CNN poll, meanwhile, discovered that even though 71 percent of voters want smaller government, vast majorities oppose cuts to Medicare (81 percent), Social Security (78 percent), and Medicaid (70 percent). Instead, they prefer to slash waste-a category that, in their fantasy world, seems to include 50 percent of spending, according to a 2009 Gallup poll.

So knowing that Japan has run relatively large deficits for 23 or so years now, has the highest public debt ratio – more than 3 times the so-called insolvency threshold (as in Rogoff and Reinhart’s myth making), close to zero interest rates, high bid-to-cover ratios at public debt tenders, and fights deflation – might be a stretch.

But for those who are still reading, here are some charts I captured from the latest edition of – Monetary Trends January 2013 – which is published by the Economic Research division of the US Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

This is a great publication as it gives a very good overview of all monetary data pertaining to the US, which then can prompt more in-depth analysis.

I was thinking that this month, the US starts to look more like Japan every day except that its unemployment rate is much higher.

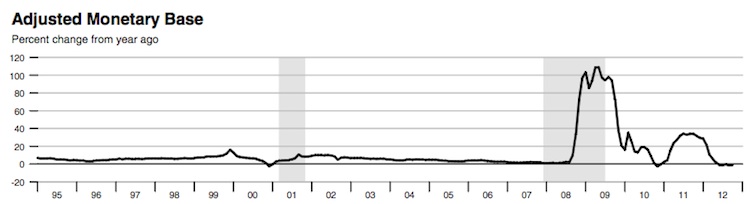

Consider these trends. The first graph shows one of the alleged culprits that was going to bring the downfall – the annual change in the monetary base. Extraordinary leap in 2008 and again in 2011 (quantitative easing). Should spell higher inflation and certainly higher inflationary expectations.

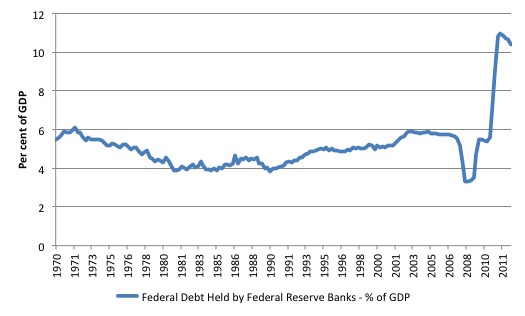

And what about this graph which shows the “Federal Debt Held by Federal Reserve Banks as Percent of Gross Domestic Product” (seasonally adjusted) as published by the US Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis – FRED2 database. This trend led to wild claims that the central bank was “monetisation”.

Remember the infamous – Secret Video – which caught Mitt Romney out hating about 50 per cent of his fellow citizens.

Here was one response by Mitt Romney during that meeting last year when he was asked by an audience member about the impending bankruptcy of the US:

… as soon as the Fed stops buying all the debt that we’re issuing-which they’ve been doing, the Fed’s buying like three-quarters of the debt that America issues. He said, once that’s over, he said we’re going to have a failed Treasury auction, interest rates are going to have to go up. We’re living in this borrowed fantasy world, where the government keeps on borrowing money. You know, we borrow this extra trillion a year, we wonder who’s loaning us the trillion? The Chinese aren’t loaning us anymore. The Russians aren’t loaning it to us anymore. So who’s giving us the trillion? And the answer is we’re just making it up. The Federal Reserve is just taking it and saying, “Here, we’re giving it.” It’s just made up money, and this does not augur well for our economic future.

The bid-to-cover ratios (concerning his “failed Treasury auction” claims) are now running above four (Source). In that article we read that the early December Treasury auction “(i)nvestors bid for more than four times the amount of two- year notes” on offer “matching a record high”. The result is that yields are low and staying low.

Last September, the New York Times ran an article – http://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/22/business/economy/as-the-us-borrows-who-lends.html and said:

What would happen if China decided to start selling Treasury bonds? And what would happen if the Fed’s appetite for government bonds were to be quenched?

Not much, it appears.

The story contains theoretical errors (that private bond markets could push up rates against the central bank’s will) but the trends reported are correct and make the sort of rabid fantasies that Mitt Romney attempted to capitalise on politically last year seem laughable.

Along the lines of Who is Kofi Annan? Answer: Coffee is a drink! I better be careful though, because I might have said that CofFEE was a – Research Centre – I have something to do with!

Anyway, back to the evidence trail.

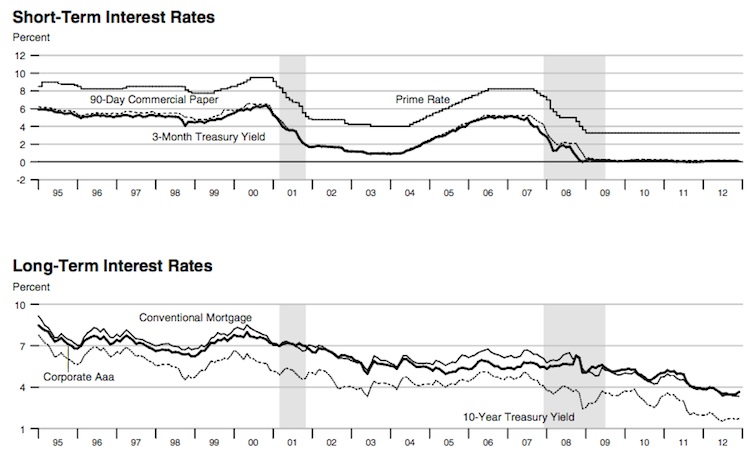

The next graph shows the movements in interest rates. Flat and low and pointing downwards. There is really nothing complicated here. The central bank controls the short-term interest rates (not the market) and, in turn, conditions the longer-term rates. The central bank can control interest rates to be whatever they desire.

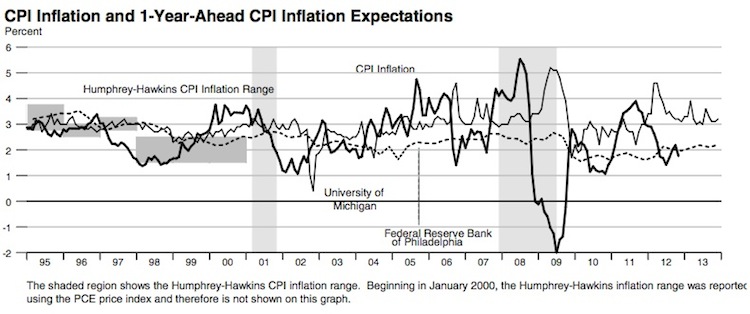

The next graph shows movements in CPI inflation and 1-year-ahead CPI inflation expectations. The inflationary expectations measures are “the quarterly Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia Survey of Professional Forecasters” and the “monthly University of Michigan Survey Research Center’s Surveys of Consumers”.

It is hard to conclude anything other than they are all flat or falling.

The FRBSF article cited above “examines how household inflation expectations have evolved since the beginning of the financial crisis in the United States and the United Kingdom”. I will deal with the UK another day.

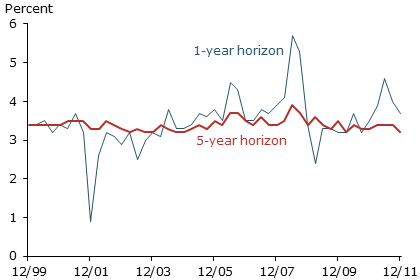

They use the monthly University of Michigan survey which “asks a random sample of approximately 500 households what changes they expect in key macroeconomic variables, such as inflation, interest rates, and unemployment. Respondents are asked their inflation expectations over the next 12 months, and 5 to 10 years out”. It is a well-known time series of inflationary expectations.

This graph is from that article. The conclusion is that while there was some volatility in “year-ahead” expectations (reflecting in part oil price swings), by “the end of the sample, year-ahead inflation expectations are significantly lower than the levels registered in late 2008.”

Longer-term inflationary expectations have “stayed in a relatively narrow range around 3%”.

The overall conclusion:

… even such a severe shock as the financial crisis did not significantly change U.S. household long-run inflation expectations. It’s worth recalling that, for most of the period of this study, the United States had no formal inflation target.

The President of the US Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, James Bullard was very clear that quantitative easing would lead to elevated inflationary expectations. His position was broadly in line with what Monetarists think.

In the July 2011 edition of the Bank’s own publication – The Regional Economist – his article The Effectiveness of QE2 – stated:

The policy change was largely priced into the markets ahead of the November FOMC meeting, as financial markets are forward-looking. The financial market effects of QE2 were entirely conventional. In particular, real interest rates declined, expected inflation increased, the dollar depreciated and equity prices rose.

Well the evidence doesn’t support the claim that inflationary expectations rose.

As I said earlier – none of the data is consistent with what our students would tell us. Which means one thing really – it is quite simple. They are being taught a model that fails in every way to embrace what happens in the real world.

All of the evidence provided above is consistent with Modern Monetary Theory (MMT).

If you trace back through our earlier academic literature since the 1990s and then the more recent “popularised” versions via our blogs you will find a consistent story and a close correspondence with the fact, which I think no other macroeconomic approach can lay claim to over such a long period of time.

Conclusion

As I said at the outset, I was going to write about the latest IMF claims about prudent and profligate fiscal positions today but generally got sidetracked in my blog time by a request from a journalist for some commentary on recent data trends.

And that is where I went after that.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Dear Bill,

Yes they have their Reinhart (and Rogoff) but we have Rinehart.

Don’t know what’s “better”.

There is a common error associated with many models in that they are too much grounded in linear thinking. The cyclicality is often disregarded and pressures for abrupt changes can build up over very lengthy periods of time. There is no equivalent for a phase transition in probably all mathematical models used by economists that e.g. will happen when the water’s temperature is reduced from plus 2 to minus 2 centigrade. What I can state with certainty is the fact that none of us knows the future.

Consider a thought experiment, where a man stands dominoes on end, on a hardwood floor close enough to each other that if one falls a “domino effect” impacting other dominoes will occur.

Day after day, we see this man come into this room and stand on end more and more dominoes. But soon we notice an open window with wind entering the room, some of the gusts appear strong enough to knock down a domino if it hits one just right. But day after day, the man comes in and stands even more dominoes on end, with the howling wind continuing. Now, we notice something else, young children are playing in the room, running around and oblivious to the dominoes. It is a big room and they are in another part of the room, but they are running, jumping, chasing each other, it is only a matter of time before they step on a domino that will start the others to fall.

Yet, day after day, the man comes in adding dominoes, some now closer to the open window, some now closer to the playing children. Is it not reasonable to warn that some, if not all, of those dominoes will come tumbling down? We can’t say which day, because it is too complex to understand exactly when the children will play near enough or which day the gust will hit a domino just right with a enough force to start the chain reaction, but we see the dangers developing in front of our eyes.

To warn about such, if we are concerned about the dominoes falling, is an important warning. To dismiss the warning because the dominoes haven’t fallen yet, or because we can’t provide a certain time when they will fall or an exact number as to how many will fall, is absurd.

Bill, do you want to comment on the Trillion Dollar Coin debate in the US?

There are a number of recent posts at New Economic Perspectives, and most recently at Interfluidity and Fed Watch that describe how the TDC idea fundamentally shows the truth of MMT, hence the action by the Treasury and Fed to try to boot it into the long grass – as it undermines so many mainstream nostrums.

If anything I think your poll references give the people I meet everyday too much credit. I would like to blame all of the ignorance spouted in the US on Fox News, but I heard twice last week from two different source on CNBC how gold is going to five thousand dollars an ounce and the dollar is going to collapse. Daily the entire news media hype crap that is entirely useless and pretend it is news and evidently people don’t understand its uselessness. I constantly hear people with absolutely no thinking ability at all quote Fox as if they are experts. Do you realize that SS, Medicare, and people on welfare are the problem with the budget? I here that from people who will soon be on SS and Medicare. It is amazing how many people are never going to get old or who are so wealthy in their own minds that they will never use social benefits and they know that because they watch television. I can understand the media using our bigotry against other people but I can’t understand how they can cause us to hate our future selves. Note I didn’t say it is right for the media to use our bigotry against anyone.

No doubt there are a lot of ignorant people in the USA and elsewhere.

I wonder what the ignorant proportion of the population is in Australia.

Seems to me that we need to fix our own glasshouse before throwing stones.

One thing that I sometimes wonder about is why we have any inflation at all in the United States, even two percent. With such large unemployment and output gap, why is it not zero, or deflation? Maybe it really is and CPI doesn’t properly measure it? Some other reason?

@ Ken

You are 100% correct in your assumption that it would be logical to have a deflationary situation in the USA that reduces the general price level.

However, the central planers or in this case the central bankers have decided that prices are not allowed to be lowered and have started to buy all kind of debt that is floating around in the system and providing the economy (actually mainly the banks) with additional currency. It is Ben Bernanke’s declared objective to flood the economy with as much money as needed to avoid a deflationary outcome.

Nothing really new as the US$ lost 92-97% of its purchasing power over the past 100 years due to the inflationary money policies of the FED.

Linus, that would be out of paradigm with MMT, which holds that these types of central bank operations are merely asset swaps and not inflationary. In fact, they are held to be slightly deflationary (at least by Warren Mosler) because of the removal of interest income from the economy.

Anyway, if the central bank’s monetary operations really did work the way you say, we’d see lots more than two percent inflation. So still looking for an explanation of the observed inflation. Is a slow price creep of a couple of percentage points somehow built-in to the system?

” I wonder what the ignorant proportion of the population is in Australia ”

The sad truth is that the average person in the street in this country is an easily manipulated ignoramus, with little or no understanding of the forces which are controlling and moulding his/her life.

@ Ken

You seem to fall for the idea that things are simply connected at the hip and one action will result in an immediate reaction in another area of the economy.

There are millions of decisions done on a daily basis in an economy and there are no simple rules as reflexes on policies are non-linear. It is probably wiser to compare an economy with an eco system than with an engine as time lags are often rather the rule than the exception. Expectations, sentiment and confidence are soft factors that cannot be easily managed by the decision makers, especially if a system is lacking sustainability. But these factors have major implications and can change attitudes that may result in unforeseen consequences.

Ken, here is Krugman’s explanation

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/07/09/why-are-wages-still-rising-wonkish/

Stephanie Flanders observes that average UK public sector wages have gone up 9% over two years because workers are entitled to “annual increments”. If labour contracts more generally have this short of annual increments it’s no wonder why prices are going up.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-20561444

Monetary policy is effective?

“Myths about quantitative easing

Some of the money for these government expenditures has come directly from “money printing” by the central bank, also known as “quantitative easing”. For over a decade, the Bank of Japan has been engaged in this practice; yet the hyperinflation that deficit hawks said it would trigger has not occurred. To the contrary, as noted by Wolf Richter in a May 9, 2012 article:

[T]he Japanese [are] in fact among the few people in the world enjoying actual price stability, with interchanging periods of minor inflation and minor deflation – as opposed to the 27% inflation per decade that the Fed has conjured up and continues to call, moronically, “price stability.” [9]

How is that possible? It all depends on where the money generated by quantitative easing ends up. In Japan, the money borrowed by the government has found its way back into the pockets of the Japanese people in the form of social security and interest on their savings. Money in consumer bank accounts stimulates demand, stimulating the production of goods and services, increasing supply; and when supply and demand rise together, prices remain stable.”

http://www.atimes.com/atimes/Japan/NI11Dh01.html

Well, Japanese enjoy falling wages. Thanks to the centralised bargaining they have been able to lower their wages across the board for years now. They are trying to do this “internal devaluation” and “competitiveness” stuff. But how is it working?

@pz

Why are you mentioning Stephanie Flanders? Her program on the economic crisis showed that she had very little understanding of what she was talking about. And she is the BBC news’s business or economics editor.

Agreed larry. Her 3-part doco was simplistic and did not generally challenge neoliberal shibboleths.

Hi Linus,

I’m inclined to agree with Ken regarding your claim that Bernanke is flooding the economy with currency to avoid deflation. Bernanke’s operation sounds like an ordinary QE operation, but staged, with some added jawboning to give the market the idea that something is being done. We know that anything that smacks of fiscal intervention is not on the political horizon.

To me it sounds like whistling in the dark. Everybody knows that it would’ve been much better had the newly printed notes been mailed out to the unemployed as a bonus payment. Or as we often hear these days, dropped out of a helicopter.

A lack of currency is not the problem facing commercial banks. It’s a lack of credible borrowers. Banks don’t need “currency” to finance lending operations. And anyway, any purchase by the Fed of bank assets will result in increased reserves, which again have nothing to do with lending.

Great piece, Bill, you guys do great work in educating us. While you have some-perfectly legitimate-fun wiht us Americans, I think it should be pointed out that the U.S. has done far better than it’s counterparts in Britain and the EU.

In the EU, this is largely because of the hopeless EU monetary strait jacket. In Brtiain however, it’s totally self imposed. Despite all of what Krugman calls our “deficit scolds” we have had comparatively less austerity in the U.S. than certainly Britain or the EU.

True, we’ve seen the states forced to cutback thanks to the failure of the federal government to give the states needed aid, at the federal level while there’s been no increase in government spending-as we need-there’s been none of the deep cuts that the GOPers want so badly.

Comparatively then we’re now a picture of health-no double dip, etc.