It's Wednesday and I discuss a number of topics today. First, the 'million simulations' that…

Exploring directions in fiscal policy

This blog extends the discussion in yesterday’s blog – Exploring pro-cyclical budget positions – which is why I am running them on consecutive days. Not that I think any of my readers (Austrian schoolers and other conservatives aside) have memory issues! The discussion that follows focuses on ways in which we can interpret the fiscal stance of a government and hopefully clears up some of the confusion that I read in E-mails I receive from readers. I say that not to put anyone down but rather to recognise that the decompositions of budget outcomes and analysing the direction of fiscal policy on a period-to-period basis is not something that the financial press usually focuses on. In avoid detailed analysis, the press leaves lots of misperceptions unchallenged and often the wrong conclusions are drawn. I am not talking about policy preferences here. Just coming to terms with the facts is sometimes difficult for many commentators to achieve. But, of-course, the “facts” are also sometimes difficult to discover given that the methods used to produce them are often ideologically biased (I am talking here about the decomposition of the actual deficit into structural and cyclical components requires a full employment benchmark, which is where the fun starts.

I wouldn’t want anyone to get the impression that I had a set on Dr Frankel. It is just that his two recent articles represent the classic deficit dove position, which unfortunately holds sway among most progressives, to the detriment of the advancement of progressive thought.

His latest Vox article (January 29, 2013) – http://www.voxeu.org/article/monetary-alchemy-fiscal-science – aims to present a discussion on the relative merits of monetary and fiscal policy for managing the macroeconomy.

Early on, Dr Frankel refers to Keynes who “was associated with support for activist or discretionary policy. The aim was a countercyclical response to economic fluctuations: expansion in recessions, discipline in booms”.

Note the terminology – “expansion in recessions, discipline in booms”. I will return to that.

Dr Frankel claims Milton Friedman – the Chicago monetarist who should bear a significant responsibility for burdening the economics profession with the sort of dud ideas that have rendered mainstream macroeconomics devoid of relevance – opposed “activist or discretionary policy” but shared with Keynes an opposition to:

… procyclical policy moves such as the misguided US tightening in 1937 at a time when the economy had not yet fully recovered.

He correctly notes that:

Many politicians in advanced countries are repeating the mistakes of 1937 today. This is happening despite conditions … qualitatively similar to those that determined Keynes’ policy recommendations in the 1930s … high unemployment, low inflation, and rock-bottom interest rates.

The conservatives in economics are not all that different to the holocaust deniers in history or the climate change deniers in whatever. They reinvent, obscure, redefine, make up stuff, and generally avoid facing the facts. That is natural when they are pushing such a flawed barrow which even the simplest understanding of the facts would reveal.

Dr Frankel thinks that “many of these lessons have been forgotten in recent decades” – whereas I would say that it is not that they have forgotten history – it is just they never understood it and if they did it was inconvenient to their agenda.

Then we encounter this:

… proponents of austerity correctly point out that the long-term consequences of permanent expansionary macroeconomic policy – both fiscal and monetary – are unsustainable deficits, debts, and inflation.

To which I say – no they don’t – correctly that is. This leads me to investigate what we mean by expansionary and contractionary fiscal policy.

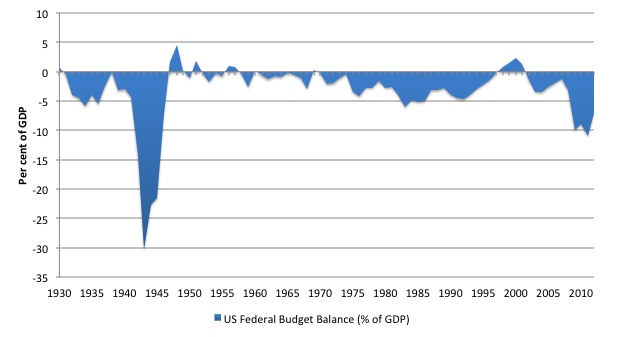

Just reflect on the following graph, which shows the US Federal Government deficit as a percent of GDP from 1930 to 2012. The data tells us that 84 per cent of the time, the US federal budget was in deficit.

Does this mean that 84 per cent of the time the US budget deficit was expansionary? Answer: yes, if by expansionary we mean contributing to growth.

Does this mean that for 84 per cent of the time the US budget deficit was appropriate? Answer: no, because we need a benchmark against which we measure appropriateness. That benchmark is usually full employment when the cyclical component of the deficit is zero. More about which soon.

Does this meant that for 84 per cent of the time the US fiscal policy decisions were expansionary? Answer: no, because we need to consider the direction of policy on a year to year (or period to period) basis before we can draw that conclusion. The existence of a a budget deficit is not a sufficient condition for us to conclude that the direction of discretionary policy stance is expansionary.

A deficit, in itself, then doesn’t necessarily signal that the government is pursuing an expansionary fiscal policy stance from period to period, although all deficits signal a net contribution to growth coming from the public sector. That might sound odd to you.

By way of repetition, the federal budget balance is the difference between total federal revenue and total federal outlays. So if total revenue is greater than outlays, the budget is in surplus and vice versa.

The budget balance is wrongly used by all and sundry to indicate the fiscal stance of the government. A budget deficit means that the government sector is injecting net spending into the economy and vice versa.

However, we cannot conclude that changes in the fiscal impact reflect discretionary policy changes. The reason for this uncertainty is that there are automatic stabilisers operating.

The most simple model of the budget balance can be written as:

Budget Balance = Revenue – Spending.

Budget Balance = (Tax Revenue + Other Revenue) – (Welfare Payments + Other Spending)

Tax Revenue and Welfare Payments move inversely with respect to each other, with the latter rising when real GDP growth falls and the former rises with real GDP growth. These components of the budget balance are the so-called automatic stabilisers

In other words, without any discretionary policy changes, the budget balance will vary over the course of the business cycle. When the economy is weak – tax revenue falls and welfare payments rise and so the budget balance moves towards deficit or the deficit rises. When the economy is stronger – tax revenue rises and welfare payments fall and the budget balance becomes increasingly positive. Automatic stabilisers attenuate the amplitude in the business cycle by expanding the budget in a recession and contracting it in a boom.

In other words, the presence of automatic stabilisers make it hard to discern whether the fiscal policy stance (chosen by the government) is contractionary or expansionary at any particular point in time.

To overcome this uncertainty, economists devised what used to be called the Full Employment or High Employment Budget. In more recent times, this concept is now called the Structural Balance.

Please read my blogs – Structural deficits – the great con job! and Structural deficits and automatic stabilisers – for more discussion on the significance of this shift in nomenclature.

The Full Employment Budget Balance was a hypothetical construct of the budget balance that would be realised if the economy was operating at potential or full employment. In other words, calibrating the budget position (and the underlying budget parameters) against some fixed point (full capacity) eliminated the cyclical component – the swings in activity around full employment.

So a full employment budget would be balanced if total outlays and total revenue were equal when the economy was operating at total capacity. If the budget was in surplus at full capacity, then we might conclude that the discretionary structure of the budget was contractionary because it was pulling more spending out of the economy than it was putting in. The opposite would apply if the budget was in deficit at full capacity.

However, even then the situation is complicated by the fact that a structural surplus might still be consistent with the direction of discretionary fiscal policy being expansionary. That is, from a surplus position, the government might seek to move the economy towards deficit by reducing the surplus. That would be an expansionary shift even though the budget balance might be dragging on growth – in this case it would be dragging less on growth than before.

How do we measure full employment? Please read my blogs – Structural deficits – the great con job! and Structural deficits and automatic stabilisers – for more discussion on that.

The modern method employed by the major multilateral agencies, central banks and government departments is usually based on some variation in the concept of the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (the NAIRU) entered the debate – see my blogs – The dreaded NAIRU is still about and Redefing full employment … again!.

The NAIRU became a central plank in the front-line attack on the use of discretionary fiscal policy by governments. It was argued, erroneously, that full employment did not mean the state where there were enough jobs to satisfy the preferences of the available workforce. Instead full employment occurred when the unemployment rate was at the level where inflation was stable.

The NAIRU has been severely discredited as an operational concept but it still exerts a very powerful influence on the policy debate. In Australia, it dominates the potential GDP or full capacity utilisation modelling.

So the decomposition of the budget into the “structural” and “cyclical” components typically uses some variation of the estimated NAIRU to benchmark the demarcation.

The problem is that the NAIRU estimates are almost spurious and biased towards higher unemployment that a reasonable definition of full employment would relate to.

The upshot is that this approach usually underestimates the tax revenue and overestimates the spending and thus concludes the structural balance is more in deficit (less in surplus) than it actually is.

They thus systematically understate the degree of discretionary contraction coming from fiscal policy.

The US Congressional Budget Office follows this defective methodology. They provide a detailed account – Measuring the Effects of the Business Cycle on the Federal Budget of how they calculate the impacts of the automatic stabilisers – that is, decompose the budget outcome into structural and cyclical components. They also provide annual and quarterly data.

In effect, their methodology leads them to understate the degree of excess capacity (that is, underestimate the GDP gap).

But whatever method they use, the CBO still attempt to net out of the actual budget balance the cyclical effects of the automatic stabilisers. The intent is to produce an estimate of the discretionary component of the budget so that a more informed commentary on government policy can be made.

On Page 3 of the CBO document we read:

Calculations of the cyclically adjusted budget attempt to remove the effects of the business cycle on revenues and outlays (that is, the cyclical part of the budget).

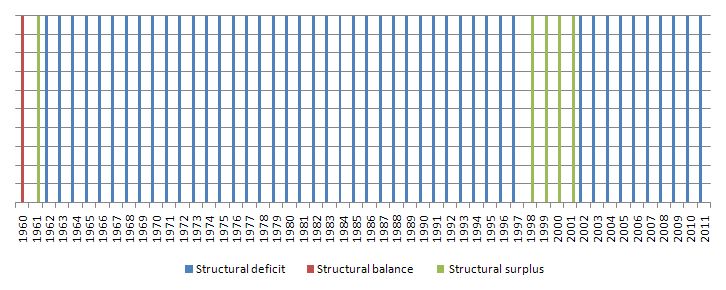

The most recent CBO data which begins in 1960. Accepting their estimates of the decomposition between structural and cyclical components at face value I produced the following graph. I gave the value 1 in each period for a structural deficit (blue column), a budget balance (red column) and a structural surplus (green column). The graph shows overwhelmingly (in a very explicit way) how many “structural deficits” there were between 1960 and 2011.

The US federal government ran structural deficits 88 per cent of the time.

If the decomposition of the structural components were available before then we would see more blue columns and hardly any green ones.

The following graph shows the decomposition of the CBO data since 1960 and the structural deficit as a percentage of GDP for the US. The normal situation over this long period has been a structural deficit.

How might this help us detect the shifts in the fiscal stance? In the previous graph, any time the structural (green) line heads upwards it signals that the shift in discretionary fiscal policy is contractionary. The opposite applies when the green line heads downwards.

So in 2001, the federal budget was in surplus (both components) but the shift in the structural component went from 1.2 per cent of potential GDP in 2000 to 0.6 per cent of GDP, which signalled an expansionary shift in fiscal policy.

Remember I would not trust the CBO potential GDP estimates. But the data allows us to get some idea of the way in which fiscal policy has shifted over this 52 year span.

The next graph expresses the data in the previous graph in a different way. The blue bars are the years when the structural deficit increased (that is, a discretionary expansion), while the red bars signify years in which the change in the structural deficit was negative (that is, a discretionary contraction).

Over the period shown, the US economy has enjoyed an overall budget deficit 90 per cent of the time, whereas the shift in the structural component of fiscal policy has been expansionary about 50 per cent of the time.

The point is that if there is a deficit of say 2 per cent of GDP today and last week it was 3 per cent of GDP, then this would not be considered a sign

I created this Table to help the discussion. The data is stylised and should be interpreted on a year to year basis.

The conclusion in Column 4 (Discretionary Policy stance) can be taken to mean what the intention of the government is in each annual budget. So in Year 1, there is a structural deficit of 3 per cent of GDP and no cyclical deficit. That means the economy is at full employment and the overall budget deficit of 3 per cent is the desired fiscal position. The impact of the government sector is expansionary in the sense that it is supporting growth (and full employment).

Then in Year 2, something happens to private spending (implied) and the economy departs from full employment. How do we know that? The cyclical component is now in deficit meaning the automatic stabilisers (triggered by the departure from full employment) have increased aggregate demand. The structural position is expansionary as is the overall fiscal position.

In the shift to Year 3, the economy deteriorates further and the structural deficit is smaller than in Year 2, signifying a contractionary fiscal position even though the overall budget balance remains the same (4 per cent of GDP) and is expansionary. The loss of discretionary net spending is offset by the automatic stabiliser boost.

In Year 4, the discretionary component moves to a larger deficit (an expansion) and the cyclical component declines, signifying a strengthening economy even though the budget deficit overall is unchanged and remains expansionary.

Year 5, fiscal austerity goes into gear and the discretionary position is contractionary and is offset by the cyclical shift as a result of the declining growth in the economy.

Finally, in Year 6, the discretionary position tightens further and the cyclical position is zero. This is not a real world example, but this might have occurred if there was a sudden boost in net exports that drove domestic growth so strongly that the economy moved back to full employment (automatic stabilisers are zero) and the overall budget into surplus. In this case, the intended impact of the government is contractionary (presumably to keep a lid on inflation) and the overall impact of the government is contractionary.

Australian Prime Minister buys into the myths

There was a major story in the Melbourne Age this morning (January 30, 2013) – PM gets tough on deals for well-off – which characterises the misconceptions that about when the public is informed of budget matters.

It also illustrates an important point about the difference between the composition of the budget and its level.

The Australian Prime Minister announced that her government was going to make “big ‘structural’ cuts in spending” in the up-coming budget (which is an election year budget – the election will be on September 14, 2013). The targets of the cuts are a “range of concessions and tax breaks enjoyed by wealthier Australians”.

She claims that the “cuts are necessary for the government to fund its signature education and disability reforms, which are likely to be the centrepiece of its campaign” to win re-election.

Apparently, the cuts “were ‘tough and necessary’ in a new ‘low-revenue environment'” which has arisen because the government has been obsessively pursuing a budget surplus at a time when non-government spending growth is relatively weak. As a consequence, tax revenue is falling as the government kills real GDP growth.

Their response – further cuts in spending to chase the cyclical cuts in revenue caused by the earlier cuts in spending. What has to give – employment growth. That is about as smart as it gets! This is a pitiful display of fiscal management.

The politics are simple. The Government is about to lose office because it has alienated everyone with its mismanagement, much of which has arisen because it has kow-towed to wealthy vested interests – for example, abandoning its early climate change initiatives; tightening refugee policy to the point it is inhumane; refusing to increase the unemployment benefit despite everyone now acknowledging it is well below the poverty line; maintaining the pernicious Northern Territory intervention (which amounts to Stalinist tactics in relation to indigenous communities; the refusal to fund public education appropriately while at the same time maintaning the conservative bias towards private education funding; and the ruthless internal party assassination of the popularly elected former Prime Minister – to name a few of the issues that have destroyed their popular appeal, after they stormed to power in 2007 with a massive majority and massive goodwill to make real changes.

Anyway, now they think by attacking high income and wealthy Australians they will re-connect with the working class tories who abandoned them long ago.

As more background, the previous conservative government which ran for 11 years and ran 10 out of 11 years of surplus while the private domestic sector was racking up record levels of debt and is now incapable of returning to the sort of spending growth that the credit-binge fuelled, had, in typical conservative form, handed out massive welfare support to the high income cohort.

Massive tax concessions, incredibly generous superannuation handouts, ridiculous handouts to the expensive private schools, aid to private hospitals and life-support funding to private health insurance companies who then sheltered behind the protection and hiked rates and took massive “management fees” out and the rest of the scams that redistributed national income to the top-end-of-town.

At the same time, the recipients of this largesse, the so-called influential Australians, were leading the charge against single mums on income support (receiving a pittance); the unemployed on the dole (they were characterised as bludgers), public school teachers (characterised as having too many holidays and being over-paid); and all the rest of the attacks on the welfare state that was funnelled into their trough.

It has been a really disgusting period in our history to see the double-standards displayed as crudely and wantonly as they have.

So even though I am a high income earner I have no problem supporting massive cuts to high-income “welfare” and all forms of corporate welfare. The problem I have is cutting government spending per se.

The Government thinks it is onto a political winner but the rising unemployment that will result from the failure to expand the budget deficit to a more appropriate growth-supporting level will be the final nail in their coffin. Everyone will realise all the hype about fiscal responsibility etc has created a policy environment which has failed to even protect jobs.

There is often a need to change the composition of the budget outcome to redirect support to one cohort and take from another. But that should not be confused with maintaining a particular level of fiscal support for growth as discussed in the earlier part of the blog.

The fact is that the Australian budget deficit is too low by at least 2 per cent of GDP. So I applaud shifts in the composition of the fiscal position but urge the government to abandon its flawed notion that running surpluses is an end in itself and a sign of fiscal responsibility – independent of what is happening elsewhere in the economy.

Conclusion

I have run out of time so there will be no extend critique of the approach taken by Dr Frankel. It is predictable.

In short:

1. Budget deficits drive up interest rates – No they don’t.

2. “One never knows, for example, when rising debt levels might suddenly alarm global investors who then abruptly start demanding higher interest rates” – when has that happened for a sovereign, currency issuing nation since 1971 (when fixed exchange rates were abandoned)?

3. “… as happened to countries on the European periphery in 2010” – the Eurozone is a special case where the member states use a foreign currency (the Euro) and have no control over monetary policy. None of what has happened in the Eurozone in terms of bond markets is applicable to currency-issuing nations. The latter can control yields on their own debt whenever they want.

4. “In the case of stimulus in the form of tax cuts, one never knows how much of the boost to disposable income will be saved by households rather than spent” – it doesn’t matter. The more that is saved the larger the stimulus has to be. A responsible fiscal position always has to be consistent and ratifying the overall saving desires of the non-government sector. If it doesn’t then the economy cannot achieve and sustain full employment.

5. “expansions in recessions, discipline in booms” – which is not the same thing as running surpluses in a boom and deficits in a recession. It is all about the direction of the discretionary policy rather than the actual balance that defines the fiscal stance.

When the economy is at full employment (booming) and nominal demand looks like exceeding the real capacity of the real economy to absorb the extra spending, then the direction of fiscal policy has to be contractionary even though there might be a large overall deficit. The size of the deficit should be determined (as in Point 4) by what the non-government sector is doing and where the economy is in relation to the full employment benchmark.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

The paragraph beginning “The politics are simple,” sums up very well the overt mistakes of Gillard Labor.

However, the problems of Labor and Liberal in Australia are deep-seated; ideological, suborned and coontrolled by oligarchic capital, particularly mining capital. Don’t forget it was a conspiracy by Gillard, her supporters, union officials and the mining magnates to dump Rudd, dump the resources super tax and install Gillard, the capitalists’ puppet.

Beyond these issues of banal, crony politics is the capitalist system itself. The problems are systemic and inhere precisely and comprehensively in the entire capitalist system. Reforms within the capitalist framework (democracy, social welfare) are always resisted and if they make progress are later wound back. Witness, 1970 to the present. This represent, an adult working lifetime of regression and return to oppressing labour and the poor. It’s the nature of the beast and intrinsic to the capitalist system itself.

Capitalism always seeks new arenas of operation, new territories and new strategems of exploitation to solve its internal crises and contradictions. Thus after the stagflation of the 1970s we had globalisation, off-shoring, retrenching the welfare state as far as possible, shifting the share of national income away from labour to capital, the private debt explosion and exploitation of the last remaining unexploited parts of the environment.

But each of these processes have final limits. You cannot off-shore to the second and third world indefinitely. Eventually they become second and first world. You cannot retrench welfare below zero welfare. You cannot reduce wages below the reporductive cost of labour. You cannot increase private debt beyond the capacity to repay. You cannot loot and destroy the entire environment and expect the economy to still run without a supporting environment.

We have now reached the end game of capitalism. I would not be confident in saying this (despite all the other apparent internal contradictions of capitalism) except that we have (very nearly) reached the one limit which can be assessed on the basis of physics, the penultimate hard science. This is the limit to growth or more precisely the hard limits imposed by the finite materials and energies (both stocks and flows) available on earth. These limits relate to input resources, waste absorption and natural cycle disruptions (CO2 cycle, N2 (nitrogen) cycle etc.

Capitalism is about to show itself to be maladapative in the extreme. Capitalism as we know it now (late stage, oligarchic, corporate, crony, imperialistic and wholly dependent on endless growth) is about to hit the wall. To use an analogy, late stage capitalism is a runaway express locomotive about to hit the Terminus. We are already so close and moving at such speed that even if we hit all the brakes, the collision would still be disastrous but might be survivable by the passengers in the last carriage. However, we are stoking the boilers (an archaic but appropraite metaphor for a fossil fuel powered system) and accelerating towards our doom. The capitalists in the smoking car (“follow the cigar smoke, find the fat man there”) think their paradise will last forever. In historic time-scales the train-wreck is very close. In fact, you can reliably say the very beginnings of the train wreck start (or started) in about 2015 plus or minus 5 years.

Our last chance, if we have one, is for the educated part of the world population to realise what is happening. It will take a series of salutary disasters whose cause is ambiguously rooted in climate change, resource depletion etc. The vast middle classes and working classes around the globe will have to start hurting and hurting badly. Then the questions will start about why our elites totally misled us about economics, the environment and our collective future. There will be an enormous set of revolutions and reactions at this juncture. The outcome is entirely uncertain. I am a material determinist but not an historical determinist.