I have received several E-mails over the last few weeks that suggest that the economics…

I wonder what the hell I have been writing all these years

I have spent almost the entire time I have been in academic life – from the time I was a fourth-year student, onto Masters, then PhD and subsequently as an teaching and research academic – studying, writing, publishing, and teaching about the Phillips curve and the link between labour markets and inflation. I have published many articles on how full employment was abandoned and how it can be restored taking care to consider how an economy that approaches high pressure might cope with the increasing nominal demands on real output. I have advanced various policy options to resolve the problem of incompatible nominal demands on such output and provided the pro and con of each. I have published some very detailed papers on those questions and my recent book – Full Employment abandoned – went into all the tedious detail of how inflation occurs and what can be done about it. But, apparently, Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) ignores “the dilemmas posed by Phillips curve analysis” as one of its many alleged sins. I wonder what the hell I have been writing all these years

Further, as well as my work on Phillips curves I also live in a small, open economy which means I have a different experience to say Americans who live in a relatively closed and very large economy. The interactions between the external and domestic sectors are different and sometimes the things Americans say about economics need to be recast when considering what will happen in a small, open economy.

I have published lots of papers on the dynamics of such economies and placed my analysis within what we are now calling Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). But apparently MMT ignores the “dilemmas confronting open economies”.

My other MMT colleagues have equally written lots about inflation. The MMT framework is built around an explicit recognition that inflation is the principle risk posed by government (and non-government spending).

So it is a great surprise to me that we have ignored that issue among other things that I thought we central to the way we reason and the arguments we present.

The most usual usage of the word – Ignore is given by Google:

Many people on the progressive side are now feeling the pinch because they have failed to let go of what is essentially mainstream macroeconomic theory, which means they are part of the problem rather than the solution.

They are beginning to attack Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) because it threatens their security as self-styled progressive gurus – wandering around pretending to present meaningful and distinct alternatives the current orthodoxy when, in fact, it takes less than a few minutes to distill everything they say back into mainstream textbook land. That makes them uncomfortable.

There is a growing claim that there is nothing new about MMT – that everything we write about is “well-understood” or “widely understood and acknowledged”. Further, apparently “everybody knows” and New Keynesians are “fully aware” that the government is not financially constrained.

It is very strange – if all the major features of MMT were so widely shared and understood – how do we explain statements from politicians, central bankers, private executives, lobbyists, media commentators etc etc that appear to not accept or understand the basic MMT claims?

Where in the vast body of macroeconomic literature – mainstream or otherwise – do we see regular acknowledgement that there is no financial constraint, for example?

Why is there mass unemployment if government officials understood all our claims? It would be the ultimate example of venal dysfunctional politics to hold that that everybody knows all this stuff but are deliberately disregarding it – for what?

Why do economists still claim that banks lend out their reserves? Why do they think that an asset swap (liquid for near liquid) engineered by the central bank will provide banks with more funds to lend as if banks wait around for deposits before they make loans?

Why don’t papers on banking indicate that loans create deposits rather than engage in the fiction that it is the other way around?

Why do economists still claim there is a monetary multiplier operating when bank reserves respond to broad monetary movements?

I could pose hundreds of like questions. I am not stupid. But I couldn’t answer any of these questions if the claim that everything MMT has proposed is passe in the extreme.

These sorts of claims then lead to statements that there is “nothing new” about MMT – a sort of put down to suggest we are just a bunch of misguided, politically naive, self-aggrandising intellectual minions.

Please note that MMT does not include the word “new” in its descriptor. Also, if some person out there can find any literature written by one of the major MMT academics or authors where there is a claim that the theoretical structure proposed and integrated by the writers is “new” please let me know. I wouldn’t waste my time by the way.

The descriptor of import is “Modern” which like all descriptors can be interpreted in a number of ways. But the way the MMT literature discusses the economy and integrates components from banking, the national account accounts, a deep understanding of the way bond, currency and labour markets work – is certainly modern.

If you think of the New Keynesian literature it employs all the dated concepts that have constrained the applicability of mainstream economics – and leaves all the essential understandings to be drawn from Keynes out of the analysis. They prefer to present a false version of Keynes based on sticky prices. Please read my blog – Mainstream macroeconomic fads – just a waste of time – for more discussion on this point.

It is clear that MMT writers borrow, absorb, integrate strands of theory dating back to Marx and before. There has never been a denial of that. But there are truly novel aspects of our approach that the vast majority of economists progressive or otherwise – who are slaves of the textbook framework – still do not understand despite the claims that everything is understood.

For example, they still talk of the “government budget restraint” and call on the neo-classical literature of the 1960s (for example, the work of Carl Christ) as the authorities in this regard.

They still think that it is the monetary operations that accompany government spending rather than the spending itself that matter. If we are worried about the inflation risk, which is what the mainstream (and the progressives that use the same framework) focus on, then whether the government sells debt to the private markets, or the central bank or to no-one, is of no consequence to the impact of the spending on inflation.

The mainstream macroeconomic textbooks all have a chapter on fiscal policy (and it is often written in the context of the so-called IS-LM model but not always).

The chapters always introduces the so-called Government Budget Constraint that alleges that governments have to “finance” all spending either through taxation; debt-issuance; or money creation. The framework never acknowledges that government spending is performed in the same way irrespective of the accompanying monetary operations.

The model claims that money creation (borrowing from central bank) is inflationary while the latter (private bond sales) is less so. These conclusions are based on their erroneous claim that “money creation” adds more to aggregate demand than bond sales, because the latter forces up interest rates which crowd out some private spending.

All these claims are without foundation in a fiat monetary system and an understanding of the banking operations that occur when governments spend and issue debt helps to show why.

So what would happen if a sovereign, currency-issuing government (with a flexible exchange rate) ran a budget deficit without issuing debt?

Like all government spending, the Treasury would credit the reserve accounts held by the commercial bank at the central bank. The commercial bank in question would be where the target of the spending had an account. So the commercial bank’s assets rise and its liabilities also increase because a deposit would be made.

The transactions are clear: The commercial bank’s assets rise and its liabilities also increase because a new deposit has been made. Further, the target of the fiscal initiative enjoys increased assets (bank deposit) and net worth (a liability/equity entry on their balance sheet).

Taxation does the opposite and so a deficit (spending greater than taxation) means that reserves increase and private net worth increases.

This means that there are likely to be excess reserves in the “cash system” which then raises issues for the central bank about its liquidity management. The aim of the central bank is to “hit” a target interest rate and so it has to ensure that competitive forces in the interbank market do not compromise that target.

When there are excess reserves there is downward pressure on the overnight interest rate (as banks scurry to seek interest-earning opportunities), the central bank then has to sell government bonds to the banks to soak the excess up and maintain liquidity at a level consistent with the target. Some central banks offer a return on overnight reserves which reduces the need to sell debt as a liquidity management operation.

There is no sense that these debt sales have anything to do with “financing” government net spending. The sales are a monetary operation aimed at interest-rate maintenance. So M1 (deposits in the non-government sector) rise as a result of the deficit without a corresponding increase in liabilities. It is this result that leads to the conclusion that that deficits increase net financial assets in the non-government sector.

What happens when there are bond sales? All that happens is that the bank reserves are reduced by the bond sales but this does not reduce the deposits created by the net spending. So net worth is not altered. What is changed is the composition of the asset portfolio held in the non-government sector.

The only difference between the Treasury “borrowing from the central bank” and issuing debt to the private sector is that the central bank has to use different operations to pursue its policy interest rate target. If it debt is not issued to match the deficit then it has to either pay interest on excess reserves (which most central banks are doing now anyway) or let the target rate fall to zero (the Japan solution).

There is no difference to the impact of the deficits on net worth in the non-government sector.

Mainstream economists would say that by draining the reserves, the central bank has reduced the ability of banks to lend which then, via the money multiplier, expands the money supply.

However, the reality is that:

- Building bank reserves does not increase the ability of the banks to lend.

- The money multiplier process so loved by the mainstream does not describe the way in which banks make loans.

- Inflation is caused by aggregate demand growing faster than real output capacity. The reserve position of the banks is not functionally related with that process.

So the banks are able to create as much credit as they can find credit-worthy customers to hold irrespective of the operations that accompany government net spending.

This doesn’t lead to the conclusion that deficits do not carry an inflation risk. All components of aggregate demand carry an inflation risk if they become excessive, which can only be defined in terms of the relation between spending and productive capacity.

But it is totally fallacious to think that private placement of debt reduces the inflation risk. It does not.

If you can find that body of thought and logic in a mainstream (or non-MMT so-called progressive) literature please let me know. I wouldn’t waste my time though on such a futile search.

That sort of logic and thinking is very “modern” and quite novel in that it is not widely acknowledged or understood. If we polled 500,000 economists on whether selling bonds reduced the expansionary effects of government spending almost every one of them would say yes. That means they do not understand how these monetary operations work. MMT emphatically does and adds that understanding to the knowledge base.

In a telephone interview I gave to the Harvard International Review (published on-line on October 16, 2011) – Debt, Deficits, and Modern Monetary Theory – I said the following:

Particular budget outcomes should never be a policy target. What the government should be targeting is real goals, by which I mean a sustainable growth rate buoyed by full employment.

Why do we want governments? We want them because they can do things that improve our welfare that we can’t do individually. In that context, it becomes clear that public policy should be devoted wholly to making sure that there are enough jobs, that poverty is eliminated, that the public health and public education systems are first class, that people who are less well off are able to become better off, etc.

From a macroeconomic point of view, the spending and tax decisions of government should be such that total spending in the economy is sufficient to produce the level of real output at which firms will employ the available labor force. This is the goal, and the particular budget outcomes must serve this goal.

None of this is to say that budget deficits don’t matter at all. The fundamental point that the original developers of MMT would make-myself or Randall Wray or Warren Mosler- is that the risk of budget deficits is not insolvency but inflation. In saying that, however, we would also stress that inflation is the risk of any kind of overspending, whether investment, consumption, export, or government spending. Any component of aggregate demand could push the economy to that point where we get inflation. Excessive government spending is not always to blame.

In sum, we’re quite categorical that we believe that budget deficits can be excessive and can be deficient as well. Deficits can be too large, just as they can be too small, and the aim of government is to make sure that they’re just right to employ all available productive capacity.

This sort of discussion then leads to the fact that some so-called progressives like the neo-liberal contrivance that central banks are apparently depoliticised and stand as independent entities. Apparently, if governments entered a partnership with its central bank to ensure all government spending was backed by appropriate bank reserve operations (with no debt issued to the private bond markets) this would severely undermine financial stability.

That sort of concern is a heartland phobia of the neo-liberals. No progressive worth their salt would sign up to it.

Please read my blog – Central bank independence – another faux agenda – for more discussion on this point.

Apparently, it is good to have a central bank that can stand up to a government because the latter has a propensity to get drunk and the former has to take the “punchbowl” away.

What the hell does that mean? Does it mean that we want a system where the democratically elected government operating within the legal framework of the nation and is pursuing a mandate can be stopped by an unelected and largely unaccountable set of officials in the central bank? Since when has that been an exemplar of progressive thought?

My view of democracy is that we vote out governments who fail. We don’t want elites (corporate or central banking or otherwise) to exercise their own agendas. They were not elected. They are not accountable in the way we construct that term in political life.

But, in fact, the “independence” is a chimera anyway. Treasuries and the central bank have to work together on a daily basis to ensure that the cash system is coherent and no financial instability occurs.

Please read my blog – The consolidated government – treasury and central bank– for more discussion on this point.

Further, it is not an act of political naivety or an act of “dismissiveness of these political economy considerations” to recommend that that we make the central banks more accountable and work more closely with treasury to deal the private bond markets out of the equation.

Clearly, the elites have created a system that works for them. That is what elites do. To then say that progressives are naive for suggesting an alternative is the ultimate wimp out. That is, after all, what a progressive position is – to challenge the orthodoxy whatever it is if there is evidence that the status quo undermines the aims of progressive society.

In the current setting – the way governments operate – both arms (bank and treasury) – is clearly undermining reasonable progressive goals. There has to be a change. Are we just going to lie down and say – well the political economy is stacked up against us so we better have another pina colada and chill out – and not be so naive as to suggest that politics by its very nature is a moving feast and paradigm changes (and even smaller) changes occur with regular historical frequency.

And then we get back to inflation.

Apparently there is no “formal modelling” to explain our ideas. Did Marx, Keynes, and many other great economists use the sort of trivial formality that pervades neo-classical approaches. No? Does that mean these economists or thinkers have “failed woefully”? I doubt it.

I remind readers of the lovely observation by American (Marxist) economist Paul Sweezy who wrote in the 1972 – Monthly Review Press – article entitled Towards a Critique of Economics that orthodoxy (mainstream) economics:

… remained within the same fundamental limits … of the C19th century free market economist … they had … therefore tended … to yield diminishing returns. It has concerned itself with smaller and decreasingly significant questions … To compensate for this trivialisation of content, it has paid increasing attention to elaborating and refining its techniques. The consequence is that today we often find a truly stupefying gap between the questions posed and the techniques employed to answer them.

I talked about these issues in the following blogs – GIGO and OECD – GIGO Part 2.

Mathematics is just a language – one of many. Sometimes it helps to sort out problems that other languages cannot solve. Usually that is not the case, especially is a social science like economics.

Further, the mathematics deployed relentlessly by mainstream economics to hide the lack of substance (the “trivialisation of content”) is second-rate anyway and laughed at by the professional mathematicians. We could write a lot about that.

The sensible principle is to use more accessible language when that is adequate to convey the idea. Some formalism is useful and we have certainly deployed it at times.

But evidently our macroeconomic framework is distilled to a Keynesian expenditure system where the government can use expansionary fiscal policy to “push the economy to full employment” but after that “taxes … must be raised to ensure a balanced budget” is created.

Apparently this “balanced budget condition must be satisfied in order to maintain the value of fiat money”. I wondered where that fiction came from. I might not have read everything my MMT colleagues have published but I know most of it and I know, in detail, everything I have written.

It is plain wrong to think that at full employment the government has to run a balanced budget to ensure there is no inflation.

The non-inflationary condition is that nominal aggregate demand has to be consistent with the real capacity to produce goods and services. What the sectoral balances might be at the point where there is full employment is contingent on many things and the government’s discretionary capacity to ensure all balances equalled zero at that point is next to zero.

It would be an extraordinary coincidence if that was the conjunction of outcomes. My understanding of the historical time series for many nations is that that conjunction has never occurred.

MMT doesn’t say anything of the sort. It is clear that the government budget balance at full employment will be determined largely by the non-government budget balance. The government position might net to a large, small, zero, small negative, large negative surplus.

There is no condition in the MMT literature for a balanced budget at full employment. The responsible policy position would be to reduce net spending at full employment if nominal demand exceeded the capacity to respond in real terms.

We don’t need a few mathematical squiggles to make that point. The lack of formalism doesn’t lead to any misunderstandings or ambiguities in terms of that point.

Any stability analysis that flows from erroneously concluding that there is some balanced budget constraint on the full employment solution is equally nonsensical and has no application.

Finally (I am running out of time), apparently, “MMT lacks an explicit theory of inflation” and more.

That is news to me. What the hell have I been doing for the last three decades?

What were all those articles and a few books I had written that I thought were about inflation, bargaining conflict, the battle of mark-ups, imported inflation via resource prices; incomes policy and indexation, and the Phillips curve and related articles – some with mathematics, many with the latest econometric modelling – actually about?

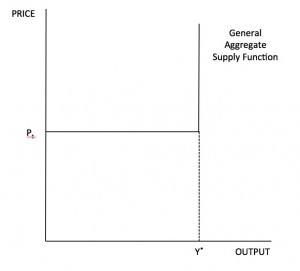

Apparently, MMT is based on “an L-shaped aggregate supply (AS) schedule” such as that below (which will appear as the first simple model in the MMT textbook I am writing with Randy Wray):

Sure enough if we assume that the price mark-up that firms use to price their goods and services and money wage rates and labour productivity (and all other unit resource costs) then it reasonable to assume that firms would supply output at a constant price – quoted in their catalogues and honour those prices for some time.

There is a cost to a firm of changing prices regularly and also a possible loss of customer loyalty.

On the horizontal portion of the supply curve, firms in aggregate will supply as much real output (goods and services) as is demanded at the current price level set according to the mark-up rule described above.

The vertical portion of the curve after full employment (Y*) is explained by the fact that the economy exhausts its capacity to expand short-run output due to shortages of labour and capital equipment. At that point, firms will be trying to outbid each other for the already fully employed labour resources and in doing so would drive money wages up.

Under normal circumstances, economy rarely approach the output level (Y*, which means that for normally encountered utilisation rates the economy typically faces constant costs.

The description of the model in the textbook acknowledged that

- If the money wage rate rises, other things equal, the unit cost level rises and the firms would translate this into a price rise via the constant mark-up.

- If there is growth in labour productivity (LP) as a result of say, increased labour force morale, increased skill levels, more technologically-based production techniques, better management, and the like, then unit costs (W/LP) will fall. This means that the firms can generate the same profit margin at lower prices. The AS function would thus shift downwards by the extent of the decline in unit costs.

- Variations in the mark-up (m) will cause the price level to change. Increases in industrial concentration, more advertising etc may lead to firms being able to increase the overall profit margin that can be sustained. Tight conditions in the goods and services market, where sales are constrained, may lead firms to reduce the mark-up desired as they all struggle for market share. This could occur as a result of flagging sales and strong trade unions pushing (successfully) for wage increases. Thus to avoid losing market share, the firms may choose to absorb some of the cost rises into the margin.

- If employment is below full employment and thus Yactual < Y*, which means there is an output gap present, then increases in aggregate demand (spending) which are seen by firms to be permanent will result in an expansion of output without any price increases occurring. If the firms are unsure of the durability of the demand expansion they may resist hiring new workers and utilise increased overtime instead. That is, they initially respond to the increased aggregate spending by increasing hours of work rather than persons employed. The higher costs (as labour productivity falls) are likely to be absorbed in the profit margin because firms desire to maintain their market share overall.

There are thus a lot of behavioural factors to be considered and analysed in each specific situation. MMT incorporates these complications in its approach to inflation. It acknowledges that bargaining is central to the wage-price bargains but also allows for industrial concentration, regulation etc to influence outcomes. We have incorporated a lot of institutional literature into our approach.

After considering all that, the draft of our text explicitly states, that:

There is some debate about when the rising costs might be encountered given that all firms are unlikely to hit full capacity simultaneously. The reverse-L shape simplifies the analysis somewhat by assuming that the capacity constraint is reached by all firms at the same time. In reality, bottlenecks in production are likely to occur in some sectors before others and so cost pressures will begin to mount before the overall full capacity output is reached.

This could be captured in Figure 9.5 by some curvature near Y*, thus eliminating the right-angle. We consider this issue in more detail in Chapter 11 Inflation and Unemployment.

That sounds like an explicit statement that there is more to our approach than the reverse-L supply curve. So surely a critic would then abandon the reverse-L claim and head for our work where we discuss unemployment and inflation (the Phillips curve) etc.

Saying things like the reverse-L is “not the way the macro economy works” is not a critique of MMT. We know that. The point is that the reverse-L is the first simple step into a macroeconomics that is not based on perfectly competitive pricing and the supply curves that arise logically from those assumptions.

We recognise (following, for example, Kalecki) that firms price firms on mark-ups and do not vary prices with variations in demand in the short-run. The reverse-L is a de-conditioning heuristic to steer students away from the continuously upward sloping supply models they get in neo-classical text books.

It is not a very difficult research task to find an extensive body of Phillips curve literature published by the MMT authors. I am known as one of the Australian economists who have consistently estimated Phillips curves in Australia over the course of my career. It is a recognised fact.

That literature also includes seminal contributions to the literature on hysteresis that challenges the vertical, non-trade-off world of the natural rate theories and allows for a non-vertical Phillips curve even if price expectations are accurate and fully adjust. I saw no mention of that literature in the recent MMT attacks.

Why not? Clearly it would make the claim that MMT “offers a false choice of unemployment versus full employment with price stability”, when, in fact, we do not offer anything of the sort, unless a major institutional change is made to render the Phillips curve dynamics irrelevant.

That change is the Job Guarantee. I note that in the recent MMT attack the discussion of the Job Guarantee and the discussion of inflation were separate and unrelated. Why? Any reasonable understanding of our approach to buffer stocks will lead a person to realise that the employment buffer approach is not a job creation program per se.

Rather it is a macroeconomic stability framework. It is a way of interrupting the dynamics that underpin the Phillips curve. If the government buys off the bottom – that is, pays the minimum price for a resource that has no bid in the private market (because there is no demand for the labour) then it cannot, in itself, add to cost pressures in the economy.

I have written extensively about that.

The Job Guarantee policy is an example of storage for use where a buffer stock wage is set below the private market wage structure, unless strategic policy in addition to the meagre elimination of the surplus of unused labour is being pursued. For example, the government may wish to combine the Job Guarantee policy with an industry policy designed to raise productivity. In that sense, it may buy surplus labour at a wage above the current private market minimum.

In the first instance, the basic Job Guarantee model with a wage floor below the private wage structure shows how full employment and price stability can be attained. While this is an eminently better outcome in terms resource use and social equity, it is just the beginning of the matter.

There are three options available to an economy, which desires price stability. First, to use unemployment as a tool to suppress price pressures as in the NAIRU approach. Second, introduce the Job Guarantee policy and use the Buffer Employment Ratio (BER) to control inflation. Third, introduce the Job Guarantee policy and augment it with an incomes policy.

Critics of the Job Guarantee approach argue that the rising budget deficits implied would be inflationary, as the NAIRU constraint would be violated. We have considered that issue many times. The nub of our argument is as follows. This is taken from my PhD.

The OECD experience of the 1990s shows that high and prolonged unemployment will eventually result in low inflation. Unemployment can temporarily balance the conflicting demands of labour and capital by disciplining the aspirations of labour so that they are compatible with the profitability requirements of capital.

Similarly, low product market demand, the analogue of high unemployment suppresses the ability of firms to pass on prices to protect real margins. The lull in the wage-price spiral could be termed a macroequilibrium state in the sense that inflation is stable.

The implied unemployment rate under this concept of inflation is termed the macroequilibrium unemployment rate (MRU) – a term I coinded in 1987 (as part of my Phd and early published work).

I noted the concept of the MRU has no connotations of voluntary maximising individual behaviour, which underpins the NAIRU concept.

As a result of the labour market changes, which accompany the business cycle, the MRU is considered to be cyclically sensitive and rises with the actual rate of unemployment. In other words, aggregate demand changes can influence the long-run steady-state unemployment rate subject to capacity constraints.

Clearly there is a minimum irreducible unemployment rate that is equal to frictional unemployment. Steady-state rates above that are subject to change as the level of activity varies. A second article I wrote in 1987 analysed this issue in detail with some formality.

Wage demands in the private sector are thus inversely related to the actual number of unemployed who are substitutes for those currently employed. When the economy slows, many workers lose their skills through obsolescence and new entrants are denied relevant skills.

Structural imbalance, which refers to the inability of the actual unemployed to constitute an effective excess supply, rises in the downturn.

Increasing the structural imbalance thus drives a wedge between effective and actual excess supply. The effective excess supply is the threat component of unemployment. To some degree, this insulates the wage demands from the cycle. The more rapid the cyclical adjustment, the higher is the unemployment rate associated with price stability.

Stimulating jobs growth decreases the wedge because the unemployed develop new and relevant work skills. These upgrading effects provide an opportunity for real growth to occur as the MRU declines.

Why will firms employ those without skills? An important reason is that hiring standards drop as the upturn begins. Rather than disturb wage structures, firm offer training with entry-level jobs. While the increased training opportunities increase the threat to those who were insulated in the recession, this is offset to some degree by the reduced probability of becoming unemployed.

The fact that at some stable inflation rate we can associate an unemployment rate and that it is increases in the latter which ensure the former does not provide a theory of why there are income distribution conflicts between powerful groups in the economy. We might also call this unemployment rate the NAIRU but in doing so we add nothing to the understanding of the inflation process.

It is clear that different theoretical underpinnings can be given to the observation and each theoretical structure brings with it an entirely different comprehension of the role of the NAIRU and what it implies for activist government agendas designed to provide full employment.

Suppose we characterize an economy with two labor markets: A (primary) and B (secondary) broadly corresponding to the dual labor market depictions. Prices are set according to markups on unit costs in each sector.

Wage setting in A is contractual and responds in an inverse and lagged fashion to relative wage growth (A/B) and to the wait unemployment level (displaced Sector A workers who think they will be reemployed soon in Sector A). A government stimulus to this economy increases output and employment in both sectors immediately.

Wages are relatively flexible upwards in Sector B and respond immediately. The compression of the A/B relativity stimulates wage growth in Sector A after a time. Wait unemployment falls due to the rising employment in A but also rises due to the increased probability of getting a job in A. The net effect is unclear. The total unemployment rate falls after participation effects are absorbed.

We could write equations out for all this – and I have. But it wouldn’t give us any greater insights.

The wage growth in both sectors may force firms to increase prices, although this will be attenuated somewhat by rising productivity as utilization increases. A combination of wage-wage, and wage-price mechanisms in a soft product market can then drive inflation. This is a Phillips curve world. To stop inflation, the government has to repress demand.

The higher unemployment brings the real income expectations of workers and firms into line with the available real income and the inflation stabilizes – a typical NAIRU story.

Introducing the Job Guarantee policy into the depressed economy puts pressure on Sector B employers to restructure their jobs in order to maintain a workforce. The Job Guarantee wage sets a floor in the economy’s cost structure for given productivity levels. The dynamics of the economy change significantly.

The elimination of all but wait unemployment in Sector A and frictional unemployment does not distort the relative wage structure so that the wage-wage pressures that were prominent previously are now reduced.

But the rising demand softens the product market, and demand for labor rises in Sector A. There are no new problems faced by employers who wish to hire labor to meet the higher sales levels. They must pay the going rate, which is still preferable, to appropriately skilled workers, than the JG wage level.

The rising demand per se does not invoke inflationary pressures as firms increase capacity utilization to meet the higher sales volumes.

What about the behaviour of workers in Sector A?

The American economist Wendell Gordon (1997: 833) said:

If there is a job guarantee program, the employees can simply quit an obnoxious employer with assurance that they can find alternative employment.

This is a long-standing claim.

With the JG policy, wage bargaining is freed from the general threat of unemployment. However, it is unclear whether this freedom will lead to higher wage demands than otherwise.

In professional occupational markets, it is likely that some wait unemployment will remain. Skilled workers who are laid off are likely to receive payouts that forestall their need to get immediate work. They have a disincentive to immediately take a Job Guarantee job, which is a low-wage and possibly stigmatized option. Wait unemployment disciplines wage demands in Sector A.

However, the demand pressures may eventually exhaust this stock, and wage-price pressures may develop.

At first blush, it might appear that the BER would have to be greater than the NAIRU for an equivalent amount of inflation control. This is because the JG workers will have higher incomes and so a switch to this policy would see demand levels higher than under a NAIRU world.

But the Job Guarantee provides better inflation proofing than a NAIRU approach because the Job Guarantee workers represent a more credible threat to the current private sector employees. In other words, the Job Guarantee pool is a more effective excess supply of labour.

The buffer stock employees are more attractive than when they were unemployed, not the least because they will have basic work skills, like punctuality, intact.

This reduces the hiring costs for firms in tight labor markets who previously would have lowered hiring standards and provided on-the-job training.

They can thus pay higher wages to attract workers or accept the lower costs that would ease the wage-price pressures. The JG policy thus reduces the “hysteretic inertia” embodied in the long-term unemployed and allows for a smoother private sector expansion because growth bottlenecks are reduced.

A further source of cost pressure comes via the exchange rate for small trading economies like Australia. Under a fixed exchange rate regime, unless there is a coordinated fiscal policy among countries it would be difficult for a small open economy to pursue its own full employment strategy.

With higher spending on imports arising from the domestic expansion, the stimulus spreads throughout the fixed exchange rate bloc and the small country would face a borrowing crisis that would negate its full employment ambitions.

It is easy to see that a Job Guarantee model requires a flexible exchange rate to be effective. We can identify two external effects. First, given the higher disposable incomes that the Job Guarantee workers would have compared to if they were unemployed imports would likely rise.

With a flexible exchange rate, the increase in imports would promote depreciation in the exchange rate. We should expect the current account to improve and net exports increase their contribution to local employment. The result depends on the estimates of the export and import price elasticities. The body of evidence available suggests that import elasticities are small (around -0.5).

We interpret this as saying that following depreciation, import spending will actually rise because while we are importing less goods and services we are paying disproportionately more for them. The improvement in the current account thus depends on the estimate of the export elasticity. In Australia, for example, these seem to high.

The direct control to allow the depreciation to be insulated from the wage-price system could be an incomes policy. If the increased spending led to depreciation, through rising imports, a comprehensive incomes policy would be required to reduce inflationary pressures.

Workers and firms would have to agree to allow real the depreciation to stick, as part of the return to the collective will. For everyone to have jobs those who are currently employed would have to sacrifice some real income to permit other to increase their claim on it. The scheme itself would not force up labour costs

The Job Guarantee wage provides a floor that prevents serious deflation from occurring and defines the private sector wage structure. However, if the private labor market is tight, the non-buffer stock wage will rise relative to the Job Guarantee wage, and the buffer stock pool drains. The smaller this pool, the less influence the Job Guarantee wage has on wage patterning.

Unless the government stifles demand, the economy will then enter an inflationary episode, depending on the behavior of labor and capital in the bargaining environment.

In the face of wage-price pressures, the Job Guarantee approach maintains inflation control by choking aggregate demand and inducing slack in the non-buffer stock sector. The slack does not reveal itself as unemployment, and in that sense the Job Guarantee may be referred to as a “loose” full employment.

This leads to the definition of a new concept, the Non-Accelerating Inflation Buffer Employment Ratio (NAIBER), which, in the buffer stock economy, replaces the NAIRU/MRU as an inflation control mechanism. The Buffer Employment Ratio (BER) is the ratio of Job Guarantee to total employment.

As the BER rises, due to an increase in interest rates and/or a fiscal tightening, resources are transferred from the inflating non-buffer stock sector into the buffer stock sector at the fixed buffer stock wage.

This is the vehicle for inflation discipline. The disciplinary role of the NAIRU, which forces the inflation adjustment onto the unemployed, is replaced by the compositional shift in sectoral employment, with the major costs of unemployment being avoided. That is a major advantage of the Job Guarantee approach.

The only requirement is that the buffer stock wage be a floor and that the rate of growth in buffer stock wages be equal or less than the private sector wages growth.

While the conflict theory of inflation is well-established, tying it into the concept of buffer stocks was a unique contribution of the MMT literature.

No person in their right mind would claim that MMT ignores inflation and has no theoretical conception of it.

Conclusion

In a most recent attack on MMT, which stirred a lot of people it seems and led to my in-box being substantially boosted over the last week, I couldn’t find any reference to my own work. I am not miffed that someone chooses not to cite my publications.

But one of the first principles you discuss with doctoral students is the need to capture all the major contributions (articles, books) in a field of study. It is not good enough to selectively ignore – that is, refuse to take notice of or acknowledge”, “intentionally disregard”, “fail to consider” – some of the major works in a field including my own. I not seeking admiration or recognition here – just stating a fact.

If a doctoral student produces a thesis which does ignore major contributions in the field they are researching the result is simple – they fail.

If a professional economist produces material that does the same thing the conclusion is simple – the work is not honest or acceptable, no matter what it says.

Going back to our definition of ignore, here are some reasonable questions that a lawyer might pose in a trial:

1. Sir, have you evidence that Prof. Mitchell has refused to take notice of or acknowledge the concepts of inflation, the Phillips curve, open economy considerations etc in his body of work spanning some 32 years of published material?

2. Sir, have you evidence that Prof. Mitchell has intentionally disregarded the concepts of inflation, the Phillips curve, open economy considerations etc in his body of work spanning some 32 years of published material?

2. Sir, have you evidence that Prof. Mitchell has failed to consider the concepts of inflation, the Phillips curve, open economy considerations etc in his body of work spanning some 32 years of published material?

Sir, I would suggest the answer to each question is an emphatic no – which means you might as well shut the F&&K up and apply yourself to reasonable levels of scholarship in the future.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

” Does it mean that we want a system where the democratically elected government operating within the legal framework of the nation and is pursuing a mandate can be stopped by an unelected and largely unaccountable set of officials in the central bank? ”

Apparently so.

We are indeed governed by a bunch of bankers

Bill. You normally reference the offender. I’m clearly not keeping up with events.

Are we talking about that investment banker Rickards ?

.

Is this the idiot that has got you wound up ?

“Usually that is not the case, especially is a social science like economics.”

I never use mathematics in my model (not directly anyway). And I’ve built many a system modelling quite complex phenomena.

I could and a branch of my field tried to move to that (formal system theory). But ultimately it failed.

And the reason it failed is because most normal people can’t understand it. It doesn’t speak to them. Trying to prove that a system is correct formally is fraught with the danger that you will make a mistake in the proof.

Ultimately the test of whether my model is right is to run the thing in the real world and see if it gives the outputs desired. Then check and adjust it so that it does it better. Until it is good enough.

At that point I might get paid.

The problem that economists have – particularly at the macro level – is that their model of the current world is essentially a form of curve fitting. And they never have to propose and implement changes in the real world and see if the reality fits the model.

Ultimately all macro economic models have underlying them a belief structure – whether that is One True Money, The Wizard of the Central Bank, or a Guarantee of a Job and Income for all. And we’ll only know if the model and the belief stack up when we implement it.

You can’t buck try it and see.

“Is this the idiot that has got you wound up ?”

No. The people in question generally never seem to venture out into the real world. Hence why they get caught with their trousers down when they do.

I get the sense that those that remain in the ivory tower are a little upset that MMT economists have actually decided to try and communicate their ideas to the rest of the world.

Thus you get a series of these quite badly written critiques that are unfortunately little more than propaganda.

A simple chat with any of the MMT economists about the concerns before hand would have outlined their approach and, yes, their beliefs.

Any reasonable critique of MMT should then really address whether the assumed aggregate behaviour implied by the interventions would actually occur and even then they should admit that circumstantial empirical evidence is subject to the bias of curve fitting and we won’t really know until we try it.

There comes a point when the model is as good as it is going to get. Then you have to run it in the real world and see what happens.

After a quick Google search it seems that this blog is in response to

A critique of MMT by Thomas Palley

Being a dedicated follower of Prof. Mitchell’s blog, after reading the first two sections of this paper I could spot one or two “creative” uses of language and selective citation, in addition to making up definitions of what state money is etc.. And i’m only an engineer that is trying to learn economics, by no means an area expert or practitioner.

The only benefit to that so called critique is that it reinforces all that Prof. Mitchell has been saying about the lack of credibility and at times shear ignorance and major cases of cognitive dissonance. So for those lucky enough to understand and appreciate MMT, this paper actually lends more credit to MMT.

Ala Saket.

Thank you. I sppose I better read it. Is that guy really a post-keynesian ?

Dear Dr. Mitchell,

Here’s a blog post by a thoughtful and scholarly US Federal Trade Commission economist:

Another Nail in the Money-Multiplier Coffin

http://uneasymoney.com/2013/02/07/another-nail-in-the-money-multiplier-coffin/

Here’s the last line:

“When regulation Q was abolished, it meant lights out for the money-multiplier.”

Your Encinitas California student,

Left Coast Bernard

I suppose the nit-picking critics of MMT who say MMT offers nothing new are in a sense correct. That is MMT is largely a re-statement of Keynes’s little phrase: “look after unemployment and the budget looks after itself”.

The big difference between MMTers and others (unfortunately including many of those who write economics text books), is that MMTers have grasped the significance of Keynes’s above phrase, whereas others have not. That is MMTers understand that the deficit and national debt are irrelevant: i.e, MMTers understand that the only real constraint on government spending is inflation.

Strikes me Bill makes a mistake when he says “The reverse-L is a de-conditioning heuristic to steer students away from the continuously upward sloping supply models they get in neo-classical text books.”

The “reverse-L” idea (and the Phillips curve, NAIRU, etc) are all to do with MACROECONOMICS. The “continuously upwards sloping…etc” has very little connection with the latter curves. I.e. the “upwards sloping” stuff is MICROECONOMICS: it’s to do with the supply and demand for apples, peanuts, etc isn’t it?

To illustrate, the upwards sloping supply line for agricultural produce in a particular country derives from the fact that the more produce is demanded (all else equal) the poorer the agricultural land the farmers will have to use. (Not of course that supply lines always slope upwards because economies of scale can outweigh “poor agricultural land” type phenomena.)

In contrast, rising marginal costs in the case of the economy AS A WHOLE (macroeconomics) is down to an entirely different cause. It’s caused by the fact that the lower unemployment is, the poorer the match between vacancies and labour available from the ranks of the unemployed.

Bill, you could view this guy’s so-called critique as an indication that you are getting through to at least some of your enemies. For, if you were viewed in the way that the US northeast elite generally views the mid-west, as beneath contempt and unworthy of being rebutted, then this “independent economist”, if this is indeed the person who has brought about this reaction, might never have raised his head above the parapet.

I read more than a few paragraphs of this drivel and agree with Ala Saket in part, except that I think this is the product of a mediocre mind. Psychologically, your reaction is understandable. However, you once asked yourself whether you were effectively beating your head against a brick wall. Well, if you were, it could be argued that stuff like this is indicative that part of the wall may be crumbling a little.

Tea-Partiers are in disgrace within core sectors of the Republican party, being blamed for the loss of the election. And in the UK, more people are becoming disgusted with Osbornian Osterity. While it does not look as though we have hit the “inflection point” yet, where the curve begins to travel in another direction, the situation looks a little more hopeful than it did even a year ago. Possibly I am being too optimistic. But I hope not.

@Neil Wilson

Wouldn’t you agree that Osborne’s “model”/theory has had a sufficient run in the real world to be able to draw conclusions concerning its empirical applicability? I would argue that it has, and if tied to the Thatcher “experiment” (coupled with Kaldor’s running critique in the Lords (published in The Economic Consequences of Mrs Thatcher), its empirical inapplicability/irrelevance becomes even more apparent, I would have thought.

Bill

Unfinished sentence.

This sort of discussion then leads to the fact that some so-called progressives like the neo-liberal contrivance that central banks are apparently depoliticised and stand as independent entities. Apparently, if governments entered a partnership with its central bank to ensure all government spending was backed by appropriate bank reserve operations (with no debt issued to the private bond markets) this would severely

Bill, in my opinion Mr. Palley is a mere tsetse fly compared to your mighty presence. You used up too much of your valuable time to swat him. You used a sledgehammer – a flick of the finger would have been sufficient.

I laughed out loud when I read his words about MMT along the lines of ‘everybody knows this stuff’ – the mainstreamers arrogance is quite stunning.

Ralph,

“It’s caused by the fact that the lower unemployment is, the poorer the match between vacancies and labour available from the ranks of the unemployed.”

Maybe I’m wrong but….

When such mismatches occur, it is often the workforce that is blamed, or the government for having poor education. It is rare, but often appropriate, to blame businesses for having an unworkable business formula and therefore unrealistic expectations of the skills which should be available. Like with all demands on rare resources, businesses should stop blaming governments entirely for this.

It’s a poor craftsman who blames his tools.

These businesses will either go bust and be replaced by ones which use the resources that are actually available. Or they will utilise technology to overcome the shortage of skills – both would be good outcomes.

Kind Regards

“What happens when there are bond sales? All that happens is that the bank reserves are reduced by the bond sales but this does not reduce the deposits created by the net spending. So net worth is not altered. What is changed is the composition of the asset portfolio held in the non-government sector.”

Bill,

Bonds aren’t only sold to banks. Most government bonds are sold to non-banks/ the public etc.

Bond sales (to non-banks) reduce the quantity of bank deposits.

“Bond sales (to non-banks) reduce the quantity of bank deposits.”

And the quantity of bank reserves assets that bank holds.

Deposits and bank reserves that were previously expanded by government spending injections.

Whether an entity has a liability directly with the government sector or via a regulated bank middleman makes no difference to proceedings.

Wow, something got you going, and the going was good.

Up to where you began describing MMT and banks, at least. Here you lost me, perhaps because I see a different pattern in Central Bank vs government and local bank relationships.

I see two paths for new money to reach the general public. First is when Government spends the new money on employees, materials, and beneficiaries. In this case, the central bank issues currency to Government and receives Government Debt. Accounts are balanced despite Government beginning to deficit spend.

Second, the central bank can deposit currency in a local bank and receive a depositor’s credit, a note of debt, or a bank stock in return. The local bank then has currency that can be loaned to worthy (maybe loosely defined) customers. The local economy’s money supply has been increased.

Both paths increase the money supply and can be expected to increase the competition for available goods and services.

The problem comes when the central bank wants to withdraw this currency. Once Government employees are paid and the local-bank-loaned-money is spent, the new holders do not want to part with their hard earned cash.

If the central bank now thinks that too much currency is overheating the economy, the central bank may decide to borrow some money from the holders they just issued money to. Government (acting as the central bank) borrowing it’s own currency! I guess this makes sense if Government does not have the will to control inflation by raising taxes, thereby recalling the former “new money”.

A little different spin on what seems to me as basically the same MMT approach to money supply.

AmEconist,

“The local bank then has currency that can be loaned to worthy (maybe loosely defined) customers. The local economy’s money supply has been increased.”

The bank does not need to have currency pre-existing to lend. Its license allows it to lend money essentially “from nowhere”. The bank loan itself creates the corresponding deposit which balances it in an accounting sense. If banks net-lend over-all they will then be required to increase their reserves to make sure cheques don’t bounce etc in the clearing system. If they cannot borrow these reserves on the inter-bank market at a reasonable rate, they can always borrow it from the central bank.

Banks don’t lend reserves or deposits.

Kind Regards

Ala Saket says:

“After a quick Google search it seems that this blog is in response to ‘A critique of MMT’ by Thomas Palley”

Palley is a low-level contractor in an EICC? (Economic-policy Industrial Congressional Complex)

Palley’s responding to requests from politicians for cover?

employees deferring, as commanded, to their “court” employers?

y

Not qualified to intervene but hell, you only live once. Maybe I’m being thick but I don’t get the distinction between bonds being sold to banks or non-banks.

Are not bond sales made because prior deficit spending requires it ala the govt budget constraint ? So are deposits actually reduced or are they just replenished ?

I realise I may be missing something because Ramanan is stressing the point but I’d be grateful if someone could straighten me out.

“It is very strange – if all the major features of MMT were so widely shared and understood – how do we explain statements from politicians, central bankers, private executives, lobbyists, media commentators etc etc that appear to not accept or understand the basic MMT claims?”

Just stumbled over a related article:

http://www.creditwritedowns.com/2013/02/japans-looming-singularity.html#utm_source=rss&utm_medium=rss&utm_campaign=japans-looming-singularity

They acknowledge:

“If You Print Your Own Money, And You Run An External Surplus, How Can There Be a Problem?”

but finally elaborate about:

“The share of government debt to total currency and deposits will soon reach close to 100%. At this point of the endgame, there is no way out for Japan: either the central bank or foreigners must take up the bid, or Japan must begin to sell off foreign assets. Markets will price in the endgame before it happens…. then it will be game over!”

.

Markets committing Hari Kari. I like it.

@Andy,

When you buy the bond your bank debits your demand-deposit account and the Fed debits the bank’s reserve account. You are then credited a time-deposit in the form of a Treasury. Net financial assets remain unchanged.

Ben. Thanks. I’ve got that.

The thread was about how the difference in how bank deposits are affected depending on whether the bond sale is made to a bank or a non-bank. I am strugglng with that distinction. The additional point I was trying to make was that the removal of bank deposits (in both cases) merely counters the previous creation of bank deposits, via deficit spending, that gave rise to the bond sale.

CharlesJ,

“The bank does not need to have currency pre-existing to lend. Its license allows it to lend money essentially “from nowhere”. The bank loan itself creates the corresponding deposit which balances it in an accounting sense.”

It seems like new currency must come from somewhere, at some time, to keep the base currency (like operating money for a business) at a manageable level. Each loan from a bank is spent and distributed in the general pattern “Loan = spent on goods and services + taxes + savings”. All the terms on the right side may come back ultimately to the bank, but the time frame is unlikely to completely support a simultaneous loan-deposit scenario for more than the initial deposit-loan instant.

I understand ‘reserves’ as a regulator’s limit to prevent extreme reuse of the identical initial currency, hopefully preventing bank runs.

Andy: Bank deposits at banks other than the Fed don’t have to do directly with bond sales. Suppose you are some kind of agent paid by the US government only in cash. You then spend your cash on US Savings Bonds or Treasury Bonds which you get directly from the government somehow. No (“private”) bank intervenes, really. The only “bank deposit” is the FR notes, cash, which you think of as your personal bank deposit at the Fed. Buying a bond through a bank with your bank deposit at that bank just puts the bank in as an intermediary, and causes them to lose reserves, just as would happen if you withdrew the money in cash from your account and bought a bond directly from the US government, as in the “agent” case above.

Maybe I’m being thick but I don’t get the distinction between bonds being sold to banks or non-banks.

There isn’t really any distinction. Banks or non-banks have to pay for US government debt the same way, with reserves, cash, HPM. In both cases, Bill’s statement “What is changed is the composition of the asset portfolio held in the non-government sector.” is correct.

Y’s point was just that “bank reserves are reduced by the bond sales but this does not reduce the deposits created by the net spending” only applies when the bank is buying a bond for itself. When someone with a bank account buys a bond with that account, both his deposit at the bank, and the bank’s reserve account are reduced. But it doesn’t change the truth of Bill’s first statement, which is the important one.

Are not bond sales made because prior deficit spending requires it ala the govt budget constraint ? No, bonds are sold only because Uncle Sam feels like selling bonds. He has a printing press, and gets bored and likes to play around with maturities and interest rates and stuff. The only “requirement” is that he needs to sell bonds (when there is no IOR) if he wants to maintain positive short term interest rates. Uncle Sam can play with his printing press however he wants, as long as his wants are logically consistent with each other.

Hi Bill,

I check your website everyday and am a big fan though non-economist. I am able to follow your logic and am a big MMT guy.

Though I have been following you for months I was excited to ‘hear’ your anger. It came out in the first paragraph and lasted throughout the post. That anger is how I feel when I listen to the news or read the papers.

Stay angry my friend!!!

I got lost in the labor: BER,NAIRU, NAIBER,MRU. But I believe!

As to the issue at hand “pity the sucker.”

neil wilson. Response to unruly federal banks.

In all the reading about the Platinum coin seigniorage a discussion of the powers of the fed was included; the point; being was what if the Treasury deposited 60 trillion dollars in the US account at the fed and the fed refused to deposit it.

To boil down my brief understanding of the discussions(and not having done a “reasonable level of …research) It seems that the Fed is under the control of Treasury and has to do what treasury tells it to.

Treasury-hence the president -can fire and hire; so – do what I am statutorily allowed to tell you to do or I’ll appoint someone who will.

Of course that presumes an executive with a pair.

Charles J,

The point I was trying to make was that all else equal, the lower unemployment, the worse the match between vacancies and available skills amongst the ranks of the unemployed. Of course, as you say, if some firm finds a way of utilising the poor range of skills available from the unemployed when unemployment is low, then that’s a “good outcome”, as you put it.

Also, better training is not necessarily a good solution to the above skill mis-match: if we all stayed in formal education till the age of 30, the above deterioration in the match between skills available and skills required would still occur as unemployment falls.

A better solution could be have the unemployed do relatively unproductive / unskilled / unsuitable work pending the appearance of a job to which they are suited. That’s what the employment element in JG does. As to any training element in JG, that could be a waste of time for reasons given.

The critics who inhabit the chattering class cannot refute the elements of MMT in any empirically observable way. In other words, they can not present an argument that is independently testable to support their criticism, on the other hand, Bill et al have provided such evidence for 30 some years.

The naysayers therefore, must choose to ignore, omit or otherwise limit their scope of examination to support their agenda.

What do you make of this Bill ?

This is modern Ireland

A monetary operation used to prevent imminent legal action by members of Parliament. ?

At the end of the first section McDonough concludes this Byzantine operation is a scam to convert credit hyperinflation into undiluted real money claims…….with interest.

http://dublinopinion.com/2013/02/12/prof-terrence-mcdonough-on-the-irish-promissory-note-deal-galway-12-feb-2013/

Given Mr. Palley’s objections are more directed at MMR than MMT, perhaps there is a job for him after all. I’m not sure a debate between MMR and MMT would worth Bill spending his time on.

Perhaps Mr. Palley could become one of the crusaders? Talk to Mr. Mosler 🙂

I have read 2 of Thomas Palley’s books and several of his articles…and would suggest that many of the responders from above do some investigation of his work as well before casting too many stones (lest one falls into Bill’s prescription for the doctoral student who fails to consider different sides of the issue). I do confess to a disappointment with the critique of MMT article written recently by Palley, which at times seemed almost like an unwarrented ad hominen attack on Randy Wray. But I do not think Palley is “the enemy”. In fact it seems to me that he has been one of the most vocal of progressive economists pointing out how badly the neo-liberals managed the globalisation phenomenum over the last three decades …with the the result of unfettered free trade agreements with the likes of China effectively pushing down middle class wages in developed in countries towards subsistence levels of emerging countries, and leaving workers everywhere fearing constantly for their jobs. I would suggest the real enemy is the neo classical / Keynesian systhesis group, who ignore completely MMT, and especially the extreme Lucas, Prescott, Kydland, Sargent, et al wing. As stated, I was disappointed in Palley’s article about MMT: I believe he has failed to read beyond some basic introductory MMT books and blogs. However, there were some nuggets of insight scattered throughout Palley’s article and we should at least be happy that his article is raising the level of discourse. However, I can certainly appreciate Bill Mitchell’s reaction (reasonable and tempered in my opinion, no ad hominen attacks for example) expressed above.

Two things I learned from this post:

1) nothing is more enraging than being misrepresented!

2) MMT doesn’t have to be progressive – the same toolkit can be used for oligarchic policies. I find this heartening since I’d feel that a theory that’s tied to a particular outcome would be a poor theory indeed.

Big Red: I’d feel that a theory that’s tied to a particular outcome would be a poor theory indeed.

Macro involves government so it is necessarily a political science. Different attitudes toward government determine different approaches to macro. But just about all approaches to macro have to address the big three political concerns – growth (production and productivity), employment, and prices stability (chiefly inflation). Different approaches can be characterized based on how they prioritize growth, employment and price stability wrt to policy effectiveness, and that is a matter of political attitude. The neat thing about MMT is that it proposes to harmonize growth, employment, and price stability, whereas other approaches assume that there must be trade-offs, e.g., between employment and inflation.

I think Martin Wolf of the Financial Times, judging from this article and others of his that I have seen, might have been reading some MMT.

the most ironic criticism of mmt must be it’s lack of mathematical models

from academics whose mathematical models fail consistently to predict

real world outcomes

as someone who has recently has discovered mmt ideas

I have to say I am unconvinced with your inflation worries

you should ignore inflation much more than you do!

without a real world experiment it is hard to know for sure

and a knowingly non financially constrained government could respond in either direction

but as extra demand would be in both quality and volume of products

as it sustainably should be and quality of products and more particularly services

often means more staffing it’s hard to quantify how inflation as a sectorial

struggle would play

it is not only the poors demand to spend that is unrealized by low income

it is also it’s desire to save

I have read mmt narrative which describes the government sector deficit

as fulfilling the private sector desire to save

well if the masses desire is anything like the hoarding instinct of the rich

that is a lot of deficit with delayed inflationary impact

whilst from advancing a political change I would say it was vital to advocate

not issuing bonds to “cover” deficits to advance a central easy to grasp

argument governments are not financially constrained in their own currency

governments could offer retirement bonds suitably inflation proof

as a means of absorbing inflationary pressures

but evaluating the limits of aggregate supply in the face of aggregate demand increase

arbitrary as you point out the real inflationary pressures would be sectional

the usual suspects housing petrol electricity where sectional profits effects

are ubiquitous

what about government in pursuit of the public purpose introducing targeted subsidy

it’s not as if they are financially constrained

cronyism you might think but are general profits in farming relatively large?

prices here have been protected by government subsidy

if not may be more of us would be turning to horse meat

and when it comes to housing and the desperate need to advance down the path

of sustainable electricity and ration the use of petrol what better pursuit of public

purpose

government spending and employment on green energy affordable housing mass transportation

can be defaltinary in consumption as well as inflationary as in production

job guarantees are not necessary to fight an inflation which has not happened

raise the broad masses spending power unemployed and employed

a universal welfare striking directly at the loss of demand the relative decline

of household income allowing some workers to actually choose more leisure!

when everyone’s a scrounger no ones a scrounger if everyone has an income

wage demands are less about survival let the private sector compete and the

government sector concentrate on it’s vital purpose health education infrastructure

with well paid extra employees!

just a quick comment,

the JG *is* an incomes policy.

😉

@The Dork of Cork

Glad you put that here, especially considering that the Finance Minister Noonan positively lauded high inflation when explaining why this was a great deal for Ireland. Of course the analogy of his house was a con, it still shows the cognative dissonance of the elite.

On the one hand bring out and support a treaty which has a 2% inlation as a target for the ECB and then suggest that the Bond replacing (likely illegal) Promissory Notes, will be easily repaid due to …. eh…. high inflation!!!

Fintan O’Toole had a good piece in the Irish Times the other day too.

http://www.irishtimes.com/newspaper/opinion/2013/0212/1224329948276.html

I read Mr Palley’s article last week and assumed we would get an answer to it here: was disappointed when I came looking for it. Well worth the wait though 🙂

I endorse the rejection of over dependence on sums, which is in this blog, and agree with Kevin Harding’s opening statement. The fetish with maths is also seen in Borio’s BIS working paper 395, where his otherwise interesting paper collapses into a demand for better models. One of the things models seem to do is remove the need for thinking from those who find that difficult: so they are more and more divorced from anything that makes sense; and apparently unaware of that fact because they do not see a need to explain their conclusions to the rest of us (as this blog notably does) in english, when nonsense on stilts would become instantly apparent. Instead they continue to believe they are actually getting sunbeams out of cucumbers, and persuade the rest of us they must be by “proving it” with very long equations predicated on initial assumptions such as “sunlight is trapped inside cucumbers”

Perhaps because of my background I do not entirely agree with the comments here about marhematics. Economics is quantitative subject and there are interrelationships which require at least simple mathematics to understand. Mathematics is more than a language – it is also a method of making logical deductions.

Nevertheless I do agree that mathematics is often wrongly applied and it certainly does not lead to correct conclusions if it starts with faulty basic principles.

I cannot claim to be an expert on MMT, nor on economics in general, and have not read all that has been written. While the arguments of MMT are quite compelling, there are questions that I have not seen answered and do require at least some simple mathematics. In fact, some of what I have read uses what I think is appropriate mathematics.

“Mathematics is more than a language – it is also a method of making logical deductions.”

It is. But economists don’t use mathematics as a tool to help find something out.

They use mathematics like medieval priests use Latin. As a way of making what they are doing completely obscure to the wider world while trying to look clever at the same time.

Interesting post. Like the emphasis on the actual mechanics of the banking system. I’m new to MMT & have a couple Qs:

1) Under MMT could the public’s interpretation of government spending–as inflationary or not inflationary–become a self-fulfilling prophecy? AKA Milton’s adaptive expectations. Regardless about empirical historical fact.. in theory, is it possible?

2) How would you explain US stagflation?

Tom Hickey

“The neat thing about MMT is that it proposes to harmonize growth, employment, and price stability, whereas other approaches assume that there must be trade-offs, e.g., between employment and inflation.”

I’m not sure I’d go that far. Palley doesn’t appear to understand MMT but he’s good on mercantilism which MMT characterizes as a non-problem.

Schofield I’m not sure I’d go that far. Palley doesn’t appear to understand MMT but he’s good on mercantilism which MMT characterizes as a non-problem.

It’s a problem only because the US govt allows it to be. As a currency sovereign, the US govt has the policy space to run a full employment budget and also enjoy the advantage of a trade deficit in real terms of trade.

Of course, the member govts of the EZ, German mercantilism is another story, since they sacrificed their policy space by adopting the euro and giving up currency sovereignty.

Give ’em hell, Bill. I have yet to find a credible critique of MMT. ALL of them are based on lack of knowledge about this great field. Thank you for always being honest and thorough.

Bill: excellent response to “Bastard Keynesian” (Joan Robinson’s term) Simon Wren-Lewis, who seems to have picked up all these silly claims from Tom Palley. Tom’s been beating this dead drum for over a decade.

The claim that we never cite our fore- fathers and mothers is ridiculous. They used to claim that we were twisting the words of people like Eisner, Lerner, Vickrey, Godley, Minsky, Keynes, Kalecki, Marx, Smith, Knapp, Innes, and on and on and on. Now they claim we fail to give credit to them!

It is on obvious why they have suddenly gone on the front foot.

The textbook is out and they will all look stupid.