I have received several E-mails over the last few weeks that suggest that the economics…

Australian government – failing in its most basic responsibility

The Australian government is demonstrating to all of us that they are mishandling fiscal policy. The background is simple. Australia saw its growth vanish and unemployment start rising in December 2008 as the financial crisis spread into the real economy. The government responded, mostly correctly, and introduced a swift and significant fiscal stimulus. The economy resumed growth, the rise in unemployment was pegged (although there wasn’t enough done to generate sufficient jobs growth), and the budget deficit rose. Before the private sector had demonstrated it could take up the spending slack and support the growth process, the Federal government became obsessed with “returning the budget to surplus”, erroneously thinking that this would separate them, politically, from the Opposition. They were wrong. The imposition of fiscal austerity has caused economic growth to slow and tax revenue growth to fall well below projections (declining world commodity prices have also not helped). First, the government abandoned their surplus promise realising that the revenue side was not going to improve sufficiently. Now, they are implying they need to hike income taxes to cover the “revenue shortfall”. If they ever had any credibility as responsible fiscal managers then it is safe to conclude they have none now. Their continued claims about maintaining a “strict fiscal policy” (read: procyclical fiscal stance) are not only moronic but they are also leading to policies which are killing growth and employment.

The ABC news story (February 13, 2013) – Swan refuses to rule out income tax hike – reported that:

Federal Treasurer Wayne Swan has refused to rule out increases in income tax as the Government tries to plug a revenue shortfall in its budget.

The Treasurer said:

What I’ll do is the responsible thing – put in place a strict fiscal policy, make sure that working Australians get a fair go, that there is incentive in the tax system, that we build up their superannuation.

The Government is running policy which is ensuring that fewer Australians are, in fact, working. Unemployment is rising as is hidden unemployment as workers drop out of the labour force because of the weak employment growth.

In recent days, the Government has learned that its Minerals Resource Rent Tax has not generated anywhere near the revenue that was expected. The forward estimate for the current year was $A2 billion and in the first six months the tax has brought in $A126 million.

The reasons for the short-fall are several but centre on the excessive concessions made to the big mining companies (to stop them mounting political action), declining price of iron ore and coal and the structure of the tax as a so-called “super profits” (any excess of profits over the long-term bond rate plus an allowance for capital). The parallel royalties that are paid to states can also be wholly offset against the federal liability.

Both large tax initiatives of this Government – the MRRT and the Carbon Tax – will not deliver anywhere near the revenue projected.

The Government’s reaction? To tighten fiscal policy even further.

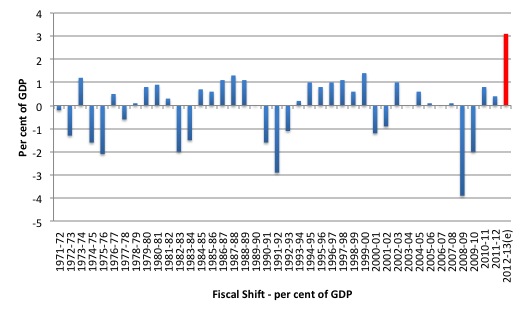

The decisions taken in the – May 2012-13 Budget – defined a planned fiscal retreat that is unprecedented in our history.

In the December 2012 – Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook 2012-13 – the Government upped the ante even further claiming that their had to be harder spending cuts in the face of clear evidence emerging that the economy was slowing and the forward estimates of revenue were overly optimistic.

At the time of the May 2012-13 Budget the planned budgetary shift was estimated to be at least $A38.5 billion. In the latest MYEFO the proposed fiscal shift is now $A44.1 billion or 3.1 per cent of GDP. That sort of shift towards surplus has never been achieved in known history.

The following graph shows annual fiscal shifts since 1972-73 in terms of proportions of GDP.

Like all austerity-seeking governments who have assumed the private sector prefers smaller deficits or surpluses and will increase spending as a consequence of a government pursuing such a fiscal shift, the Australian government is in denial of not only the objective circumstances that exist at present (rising unemployment; outstanding and massive private debt overhang from the pre-crisis credit binge; declining terms of trade which is undermining $A export revenue but also discouraging further investment growth in the mining sector, etc), but also basic psychology.

The non-mining economy is in near recession at present with unemployment undermining income growth and non-mining investment very weak. Basic psychology tells us that in those situations private spending binges of the size required to “more than offset” the public cutbacks will not be forthcoming.

However, there was also some dishonesty in the way the government presented the data.

In the May 2012-13 Budget statement it was obvious that at least $A8.5 billion in spending that will flow this year was shifted to be recorded against the 2011-12 outcome. So the deficit in 2011-12 was artificially inflated, which just happened to allow them to record a paper surplus despite the degree of contraction associated with the 2012-13 fiscal position being less than would be forthcoming if there really had have been a 3.1 per cent of GDP withdrawal in one year.

In other words, the degree of contraction this fiscal year is actually less in 2012-13 than the nominal figures suggest. How much less is a guess but if we subtract the $A8.5 billion from last year and add it to this year then you are talking a $A27 billion fiscal shift, which is about 1.8 per cent of GDP.

More importantly, this means the underlying fiscal position in 2012-13 is not a surplus at all but a deficit of some $A7.4 billion (0.5 per cent of GDP).

Whatever the actual numbers turn out to be, and the deviousness aside, the direction of fiscal policy is completely wrong. Even if it ends up being a 1.8 per cent of GDP contraction that scale of fiscal shift i one year is also unprecedented historically and is totally unsuitable at a time when non-government spending will not offset the loss of public net spending.

The question that has to be asked is under what circumstances would a Government be responsible in taking out net spending equivalent to 1.8 per cent of GDP in one year (when inflation is forecast to be constant or falling)?

You have to ask this question in the context of actual real GDP growth has slowed since the June-quarter last year and is now well below trend growth of 3.25-3.5 per cent. It is likely to be running at around 2 per cent per annum at present and trending downward. The main growth engine – private investment has slowed as a result of the slump in commodity prices.

Please read my blog – Australia National Accounts – its getting worse – for my discussion of the September-quarter National Accounts that came out in early December 2012.

But the only way it would be responsible for the Government to consider such a fiscal withdrawal would be if the economy was pushing well above trend and straining the inflation barrier – with full employment and zero underemployment – and private growth would have to be very strong and becoming even stronger during the forecast period.

There have never been conditions like that in the last 40 years. Nor was there any possibility of those conditions being realised in the foreseeable future.

That is why the scale of fiscal withdrawal announced in the last Budget was a demonstrable act of vandalism and driven by misguided (miscalculated) political machinations and is devoid of any economic rationale. Those machinations considered that if the government shouted hard enough and long enough about the virtues of a budget surplus then people would support their claim that the government was a responsible fiscal manager.

But with growth declining and unemployment rising the political calculations will turn out to be amiss.

And now the Government is hinting at more austerity in the upcoming May budget – which will take the fiscal debate into the election year.

They should read the recent article by the Financial Times (February 12, 2013) – The case for helicopter money – written by its economics correspondent Martin Wolf.

The helicopter references comes from Milton Friedman’s suggestion in the introduction (page 4) to his collection of essays – ‘The Optimum Quantity of Money and other Essays”, Chicago: Aldine Publishing Company, 1969 – that a chronic episode of price deflation could be resolved by “dropping money out of a helicopter”.

While I do not agree with all the points that Martin Wolf raises and the terminology used, the basic tenor is sound. He is considering macroeconomic policy choices and indicates that:

Measures of broad money have stagnated since the crisis began, despite ultra-low interest rates and rapid growth in the balance sheets of central banks.

The erroneous money multiplier model in mainstream economics textbooks between bank reserves and the “stock of money”. Please read my blog – Money multiplier and other myths – for more discussion on this point.

In Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) there is very little spoken about the money supply. In an endogenous money world there is very little meaning in the aggregate concept of the “money supply”.

Central banks do still publish data on various measures of “money”. The RBA, for example, provides data for:

- Currency – Private non-bank sector’s holdings of notes and coins.

- Current deposits with banks (which exclude Australian and State Government and inter-bank deposits).

- The M1 measure – Currency plus bank current deposits of the private non-bank sector.

- The M3 measure – M1 plus all other ADI deposits of the private non-ADI sector. So a broader measure than M1.

- Broad money – M3 plus non-deposit borrowings from the private sector by AFIs, less the holdings of currency and bank deposits by RFCs and cash management trusts.

- Money base – Holdings of notes and coins by the private sector, plus central bank reserves (deposits of banks with the Reserve Bank and other Reserve Bank liabilities to the private non-bank sector.

Note that ADI are Australian deposit-taking institutions; AFI are Australian financial intermediaries; and the RFCs are Registered Financial Corporations. Here is the RBA’s excellent glossary for future reference.

The mainstream theory of money and monetary policy asserts that the money supply (volume) is determined exogenously by the central bank. That is, they have the capacity to set this volume independent of the market. The monetarist portfolio approach claims that the money supply will reflect the central bank injection of high-powered (base) money and the preferences of private agents to hold that money. This is the so-called money multiplier.

So the central bank is alleged to exploit this multiplier (based on private portfolio preferences for cash and the reserve ratio of banks) and manipulate its control over base money to control the money supply.

To some extent these ideas were a residual of the commodity money systems where the central bank could clearly control the stock of gold, for example. But in a credit money system, this ability to control the stock of “money” is undermined by the demand for credit.

The theory of endogenous money is central to the horizontal analysis in MMT. When we talk about endogenous money we are referring to the outcomes that are arrived at after market participants respond to their own market prospects and central bank policy settings and make decisions about the liquid assets they will hold (deposits) and new liquid assets they will seek (loans).

The essential idea is that the “money supply” in an “entrepreneurial economy” is demand-determined – as the demand for credit expands so does the money supply. As credit is repaid the money supply shrinks. These flows are going on all the time and the stock measure we choose to call the money supply, say M3 is just an arbitrary reflection of the credit circuit.

So the supply of money is determined endogenously by the level of GDP, which means it is a dynamic (rather than a static) concept.

Central banks clearly do not determine the volume of deposits held each day. These arise from decisions by commercial banks to make loans. The central bank can determine the price of “money” by setting the interest rate on bank reserves. Further expanding the monetary base (bank reserves) as we have argued in recent blogs – Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary – does not lead to an expansion of credit.

At a time when the private sector was in recession and overburdened with debt it was obvious that the demand for credit would be low and subdued for some time.

That is why proponents of MMT predicted correctly that the expansion of central bank balance sheets (via quantitative easing and other so-called non-standard monetary operations) would not see a “blowout” in the money supply.

Martin Wolf provided the following graph to support his statement that “Measures of broad money have stagnated since the crisis began”.

He says that for the US:

Data on “divisia money” (a well-known way of aggregating the components of broad money), computed by the Center for Financial Stability in New York, show that broad money (M4) was 17 per cent below its 1967-2008 trend in December 2012. The US has suffered from famine, not surfeit.

Why is that?

Martin Wolf says (quoting from a paper by Claudio Borio – – The financial cycle and macroeconomics: What have we learnt? – from the BIS):

… deposits are not endowments that precede loan formation; it is loans that create deposits … [non direct quote follows] … Thus, when banks cease to lend, deposits stagnate.

I considered the paper from Borio in this blog (December 17, 2012) – What have mainstream macroeconomists learn’t? Short answer: nothing.

The full context for that quote in the BIS paper – which urged us to take a “more fundamental, step” is:

… to capture more deeply the monetary nature of our economies … models should deal with true monetary economies, not with real economies treated as monetary ones … Financial contracts are set in nominal, not in real, terms. More importantly, the banking system does not simply transfer real resources, more or less efficiently, from one sector to another; it generates (nominal) purchasing power. Deposits are not endowments that precede loan formation; it is loans that create deposits. Money is not a “friction” but a necessary ingredient that improves over barter. And while the generation of purchasing power acts as oil for the economic machine, it can, in the process, open the door to instability, when combined with some of the previous elements. Working with better representations of monetary economies should help cast further light on the aggregate and sectoral distortions that arise in the real economy when credit creation becomes unanchored, poorly pinned down by loose perceptions of value and risks … move away from the heavy focus on equilibrium concepts and methods to analyse business fluctuations and to rediscover the merits of disequilibrium analysis …

The BIS paper clearly would not explicitly acknowledge MMT, regular readers will identify standard MMT constructs in the previously quoted paragraph, that Martin Wolf draws upon.

You will see that it eschews the mainstream analysis of banking, which relies on the money multiplier to link the central bank to the money supply and constructs private banks as being deposit-taking institutions, which then on-lend those deposits in ways that conform to the resource allocation patterns determined by profit-maximising, market-driven, optimising private agents.

Nothing, of-course, could be further from the truth. Deposits do not “create” loans. Loans create deposits. The money supply is endogenously driven by the credit demand from the private sector, who have no claim to being rational and optimising. The GFC has dispelled that myth – as previous crises have dispelled it in the past. It is just that, in the words of the BIS paper, “(s)o-called ‘lessons’ are learnt, forgotten, re-learnt and forgotten again.”

I would have said the so-called “lessons” are denied by an ideological arrogance that is intent on defending the hegemony of the paradigm and the rewards that delivers the main players rather than advancing any notion of knowledge or insight.

This also resonates with a speech (December 8, 2011) – Challenges to monetary policy in 2012 – made by the Vice President of the European Central Bank – one Vítor Constâncio (given to the 26th International Conference on Interest Rates held in Frankfurt).

Vítor Constâncio said that:

Central bank reserves are held by banks and are not part of money held by the non-financial sector, hence not, per se, an inflationary type of liquidity. There is no acceptable theory linking in a necessary way the monetary base created by central banks to inflation. Nevertheless, it is argued by some that financial institutions would be free to instantly transform their loans from the central bank into credit to the non-financial sector. This fits into the old theoretical view about the credit multiplier according to which the sequence of money creation goes from the primary liquidity created by central banks to total money supply created by banks via their credit decisions. In reality the sequence works more in the opposite direction with banks taking first their credit decisions and then looking for the necessary funding and reserves of central bank money. As Claudio Borio and Disyatat from the BIS put it: “In fact, the level of reserves hardly figures in banks´ lending decisions. The amount of credit outstanding is determined by banks´ willingness to supply loans, based on perceived risk-return trade-offs and by the demand for those loans” … In modern banking sectors, credit decisions precede the availability of reserves in the central bank. As Charles Goodhart pointedly argued, it would be more appropriate talking about a “Credit divisor” than about a “Credit multiplier”.

Martin Wolf continues and suggests that the way forward is two-fold.

1. “it is impossible to justify the conventional view that fiat money should operate almost exclusively via today’s system of private borrowing and lending?” Which leads to two key questions:

- “Why should state-created currency be predominantly employed to back the money created by banks as a byproduct of often irresponsible lending?”

- “Why is it good to support the leveraging of private property, but not the supply of public infrastructure?”

These are questions that MMT has been proposing for some years and a satisfactory answer is never provided by mainstream economists. We get nonsense about inflation accelerating, interest rates skyrocketing, exchange rates tumbling or appreciating unduly as current accounts go crazy, financial collapse, government bankruptcy – and all the rest of the nonsense.

2. “in the present exceptional circumstances, when expanding private credit and spending is so hard, if not downright dangerous, the case for using the state’s power to create credit and money in support of public spending is strong”.

That is, the chimera of financial constraints that see governments match deficits $-for-$ with private bond issuance should be abandoned. The government should just explicitly partner with its central bank to facilitate fiscal stimulus spending that is orientated to employment generation in the context of failing economies labouring under inadequate private spending.

Martin Wolf says “Why not employ monetary financing to recapitalise commercial banks, build infrastructure or cut taxes? The case for letting fiscal deficits facilitate private deleveraging, without undue expansion in overt public debt, is surely also strong”.

Strong and sound.

As to helicopters, I wrote about that misconception in this blog – Keep the helicopters on their pads and just spend.

Conclusion

The Australian government should take heed of this advice and abandon the notion that sound fiscal policy means surpluses and that pro-cyclical policy is justifiable. Neither proposition is true and the pursuit of the former via the latter is downright dangerous because it undermines employment growth and causes many people (millions, tens of thousands – depending on the scale of the labour force) to lose their jobs.

A government that deliberately puts its own people out of work has failed in its most basic responsibility.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

I am deeply grateful for this blog.

One of the key take-aways I got from embracing MMT is that the Money Supply is critically dependent on money demand. It reinforced my understanding that Friedman was wrong (money is neutral; it’s a veil and other neo-classical concepts just don’t stack up in practice).

While I still have much to learn, I reckon I know more about economics than Wayne Swan or Joe Hockey ever will!

Keep up the good work, Bill, and for God’s sake, show the country you really care and run for the senate. You will get my vote, as will Julian Assange.

This is about the sixth time I’ve called for you to do this. Don’t wait another minute. This is the ideal time!!!

Cheers 🙂

I am intrigued by the relationship between fiat money and credit (debt?) money in an economy like Australia’s. I hope Bill can answer my propositions as if they were questions. That is, point out if they are true or false.

1. There seem to be two important kinds of money, fiat money and credit money.

2. Fiat money, considered in isolation, is created by government deficit spending.

3. Credit money, considered in isolation, is created by banks making loans.

4. Fiat money, considered in isolation, exists until destroyed by taxes.

5. Credit money, considered in isolation, exists until destroyed by loan repayment.

6. Credit money, considered in isolation, can also be destroyed by defaulting on loans.

7. Thus what is important (for the stimulus vs. austerity argument) is not the expansionary or contractionary effects of these money types in isolation but the net expansionary or contractionary effects of these money types acting in combination.

8. Why permit these two kinds of money? A natural monopoly for fiat money by the govt (which makes sense) but a kind of “guild monopoly” which allows banks to create credit money and which does not make sense except as a kind of special privilege for banking capital. What is the rationale which has permitted, allowed and enabled this rather odd system?

@ ikonoclast

It should be added that final settlement of exchange after netting is in the government’s money, which takes place in the government payment system, where the central bank acts as lender of last resort to ensure that there is always sufficient liquidity to clear.

Why two kinds of money? The argument against is that the bank lobby has sufficient political clout to extract a profitable franchise from government for practically no cost, including not only bank credit money creation but also govt money creation through bond issuance that creates default risk free safe assets with an interest subsidy.

The argument for is that government chooses to delegate a significant portion of money creation to private credit extension in the interest of political neutrality and efficiency by letting the private sector handle risk management. Otherwise in allocating capital, govt would be picking winners and losers, and this would invite more cronyism and corruption than exists already.

Tom,

That is a masterfull and succinct summary of a major issue in our current era. Please cut and paste it somewhere safe for future reference.

Entrenched political parties gaining too much power with no unaccountability is as big an issue as a small cohort of private individuals gaining great economic power and monopoly. Seems we are getting the worst of both worlds.

Please excuse my fun play on grammar……. taking liberties with “la double négation”.

Ikonoclast, there is ultimately only one kind of money. Fiat money, state money is a type of credit money. The government’s credit money isn’t the top money because it calls itself the government, it is the top money because of the real world power and extensive operations of the government, particularly its taxing power. This makes everyone happy to hold the government’s liabilities as the penultimate settlement of, the measure of all other debts. In a hyperinflation, this is no longer true.

Also, #2 should be just plain spending, not deficit spending.

The monopoly that banks have is not on credit creation, which anyone can do, but the fact that modern governments stand behind the banks by monetizing bank credit for all purposes except settlements with the government, (The monetization is done by accepting bank deposits for tax payments from non-banks, by lending to banks on demand etc.)

Bank loans provide capital for investments. You could not get enough government money ie. money without private debt into the economy to fund investments, because that money directly increases wealth of the citizens and they would start to spend too early.

Most people think about money as some kind of homogenious substance that you can just “pour more” to the economy, and it will directly increase aggregate demand. In this sense they think about it as a synonym for “wealth”.

But private money comes as a counterpart of private debt, so at first glance it should cancel itself out and provide no wealth effect. Hovewer rising private debt levels are often (always?) accompanied by real assets that are put into place. Those real assets, seems to me, increase private sector wealth and do produce some kind of wealth effect.

So in discussions about money everything that increases private sector’s wealth has the effect that is usually attributed to “increase in money stock”.

Ikonoclast

One small correction to your (6): Contrary to widespread blogospheric misconception, bank credit is not destroyed by loan default, at least not directly. There may be secondary effects on bank credit due to capital impairment from loan defaults, but no-one has their bank deposit destroyed when they default on a loan; bank capital takes the hit while their deposit liabilities remain unchanged.

Further to my previous comment, defaults on bank loans are still NFA neutral for the sector as a whole – NFA (banks) decreases by the equivalent amount to which NFA (non-banks) increases.

Wayne Swan’s unrealistic obsession with achieving a budget surplus eventually had to confront the light of day. He was always the weakest link in the Labor cabinet, in terms of (a) his poor understanding of macroeconomics and (b) his poor judgement and political acumen, in making claims and promises which relied on some very risky assumptions. As a result of his previous grandstanding he now has much egg on his face, as does the prime minister — who was very foolish to place so much trust in the competence of her Treasurer.

With Australia’s high youth unemployment–which many blame on a high minimum wage–and the shortage of skilled labor, AND the high cost of living, why would an injection of stimulus, anti-austerity, help this? And I am sorry, but I do not understand what you mean by “procyclical” since I thought everything should be procyclical–does it not mean pro-growth? Many thanks for your blog; I am re-educating myself on macroeconomics and find MMT to be, well, truthful and practical.