It’s Wednesday and I just finished a ‘Conversation’ with the Economics Society of Australia, where I talked about Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and its application to current policy issues. Some of the questions were excellent and challenging to answer, which is the best way. You can view an edited version of the discussion below and…

Unemployment and Inflation – Part 10

I am now using Friday’s blog space to provide draft versions of the Modern Monetary Theory textbook that I am writing with my colleague and friend Randy Wray. We expect to complete the text during 2013 (to be ready in draft form for second semester teaching). Comments are always welcome. Remember this is a textbook aimed at undergraduate students and so the writing will be different from my usual blog free-for-all. Note also that the text I post is just the work I am doing by way of the first draft so the material posted will not represent the complete text. Further it will change once the two of us have edited it.

This is the continuation of the Chapter on unemployment and inflation – the series so far is:

- Unemployment and inflation – Part 1

- Unemployment and inflation – Part 2

- Unemployment and inflation – Part 3

- Unemployment and inflation – Part 4

- Unemployment and inflation – Part 5

- Unemployment and Inflation – Part 6

- Unemployment and Inflation – Part 7

- Unemployment and Inflation – Part 8

- Unemployment and Inflation – Part 9

I am now continuing the discussion of the Phillips Curve …

Chapter 12 – Unemployment and Inflation

MATERIAL HERE NOT REPEATED

[PICKING UP FROM HERE]

|

Advanced material – The Rational expectations hypothesis

An extreme form of Monetarism, which became known as New Classical Economics posits that no policy intervention from government can be successful because so-called economic agents (for example, household and firms) form expectations in a rational manner. This literature, which evolved in the late 1970s claimed that government policy attempts to stimulate aggregate demand would be ineffective in real terms but highly inflationary. The theory claimed that as economic agents formed their expectations rationally, they were able to anticipate any government policy action and its intended outcome and change their behaviour accordingly, which would undermine the policy impact. For example, individuals might anticipate a rise in government spending and predict that taxes would rise in the future to pay back the deficit. As a result the private individuals will reduce their own spending to save for the higher taxes and that action thwarts the expansionary impact o the public spending increase. Recall that under adaptive expectations, economic agents are playing catch-up all the time. They adopt to their past forecasting errors by revising their current expectations of inflation accordingly. In this context, Monetarists like Milton Friedman claimed that the government could exploit a short-run Phillips curve for a time with expansionary policy by tricking workers into thinking their real wages had risen when in fact their money wage increases were lagging behind the inflation rate. But Monetarists considered the unanticipated inflation would induce the workers to supply a higher quantity of labour than would be forthcoming at the so-called natural rate of output (defined in terms of a natural rate of unemployment). Under adaptive expectations, the workers take some time to catch up with the actual inflation rate. Once they adjust the actual inflation rate and realise that their real wage has actually fallen they withdraw their labour back to the natural level. The use of adaptive expectations to represent the way workers adjusted to changing circumstances was criticised because it implied an irrationality that could not be explained or appear reasonable. In a period of continually rising prices, workers would never catch up. Why wouldn’t they realise after a few periods of errors that they were under-forecasting and seek to compensate by overshooting the next period? The theory of rational expectations was developed, in part, to meet these objections. Economic agents, when forming their expectations were considered to act in a rational manner consistent with the assumptions in mainstream microeconomics pertaining to Homus Economicus. This required that economic agents used all the information that was available and relevant at the time when forming their views of the future. What information do they possess? The rational expectations (RATEX) hypothesis claims that individuals essentially know the true economic model that is driving economic outcomes and make accurate predictions of these outcomes. Any forecasting errors are random. The proponents of RATEX said that predictions derived from rational expectations are on average accurate. Proponents of the rational expectations (RATEX) hypothesis assumed that all people understood the economic model that policy makers use to formulate their policy interventions. The most uneducated person is assumed to command highly sophisticated knowledge of the structural specification of the economy that treasury and central banks deploy in their policy-making processes. Further, people are assumed to be able to perfectly predict how policy makers will respond (in both direction and quantum) to past policy forecast errors. According the RATEX hypothesis, people are able to anticipate both policy changes and their impacts. As a result, any “pre-announced” policy expansions or contractions will have no effect on the real economy. For example, if the government announces it will be expanding the deficit and adding new high powered money, we will also assume immediately that it will be inflationary and will not alter our real demands or supply (so real outcomes remain fixed). Our response will be to simply increase the value of all nominal contracts and thus generate the inflation we predict via our expectations. The government can thus never trick the private sector. The introduction of rational expectations into the debate, thus, went a step further than the Monetarists who conceded that governments could shift the economy from the “natural level” by introducing unanticipated policy changes. The New Classical Economics denied that governments could alter the course of the real economy at all. In other words, there was not even the possibility of a short-run trade-off between inflation and the unemployment rate. Workers would always know the future inflation rate and build it fully into each round of money wage bargaining. The economy would thus always stay on the long-run Phillips curve. While there are some very sophisticated theoretical critiques of the RATEX hypothesis (for example, the Sonnenschein-Mantel-Debreu theorem) which extend the notion of the fallacy of composition where what might be valid at the individual level will not hold at the aggregate level, some simple reflection suggests that the informational requirements necessary for the hypothesis to be valid are beyond the scope of individuals. A relatively new field of study called behavioural economics has attempted to examine how people make decisions and form views about the future. The starting point is that individuals have what are known as cognitive biases which constrain our capacity to make rational decisions. RATEX-based models have failed to account for even the most elemental macroeconomic outcomes over the last several decades. They categorically fail to predict movements in financial, currency and commodity markets. The 2008-09 Global Financial Crisis was not the first time that models employing rational expectations categorically failed to predict major events. Rational expectations imposes a mechanical forecasting rule on to individual decision-making when, in fact, these individuals exist in an environment of endemic uncertainty where the future is unknowable. As we will see in later Chapters, endemic uncertainty is a major problem facing decision-makers at all levels and of all types in a capitalist monetary economy. The existence of uncertainty gives money, the most liquid of all assets, a special capacity to span the uncertainty of time. In the real world, people have imperfect knowledge of what information is necessary for forecasting and even less knowledge of how this choice of information will impact on future outcomes. We also do not know how we will react to changing circumstances until we are confronted with them. The nature of endemic uncertainty is that we cannot know the full range of options that might be presented to us at some time in the future. |

12.X Hysteresis and the Phillips Curve trade-off

While the focus of economists was on trying to estimate how fast individual expectations responded to rising inflation and the role that inflationary expectations played in wage and price formation, a new strand of literature emerged which challenged the Monetarist contention that their was no long-run trade-off between inflation and the unemployment rate.

At the empirical level it was noted that the estimates of the unobserved natural rate (sometimes called the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (NAIRU)) derived from econometric models seemed to track the actual unemployment rate with a lag.

At the time that Monetarism became influential in economic policy making unemployment rates rose after the major oil price rises in the early and mid-1970s. We will examine this period separately later.

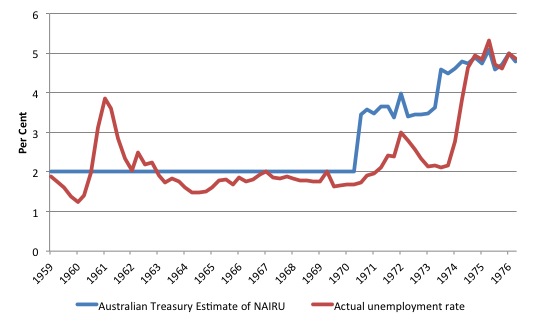

The estimates of the natural rate seemed to rise to. For example, consider Figure 12.12 which shows the Australian Treasury estimate of the NAIRU from 1959 to 1976, the latter part of this period being highly turbulent and marked the end of the Post-War full employment era where unemployment rates were usually below 2 per cent.

You can clearly see that the estimated NAIRU tracks the actual unemployment rate.

Figure 12.12 Australian unemployment rates and Treasury NAIRU estimates

These observations led economists to question the idea that there was a cyclically-invariant natural rate of unemployment. It appeared that the best estimates of the unemployment rate that was consistent with stable inflation at any point in time were highly cyclical.

A new theory emerged to explain the apparent cyclical relationship between the equilibrium unemployment rate and the actual unemployment rate. It was called the – hysteresis hypothesis.

The early work in this field showed that the increasing NAIRU estimates (based on econometric models) merely reflected the decade or more of high actual unemployment rates and restrictive fiscal and monetary policies, and hence, were not indicative of increasing structural impediments in the labour market?

It was also shown that there was no credibility in the claims that major increases in unemployment are due to the structural changes like demographic changes or welfare payment distortions.

The hysteresis effect describes the interaction between the actual and equilibrium unemployment rates. The significance of hysteresis is that the unemployment rate associated with stable prices, at any point in time should not be conceived of as a rigid non-inflationary constraint on expansionary macro policy. The equilibrium rate itself can be reduced by policies, which reduce the actual unemployment rate.

The importance of hysteresis is that a long-run inflation-unemployment rate trade-off can still be exploited by the government and one of the major planks of Monetarism would be invalid.

One way to explain this is to focus on the way in which the labour market adjusts to cyclical changes in economic activity.

Recessions cause unemployment to rise and due to their prolonged nature the short-term joblessness becomes entrenched in long-term unemployment. The unemployment rate behaves asymmetrically with respect to the business cycle which means that it jumps up quickly but takes a long time to fall again.

The non-wage labour market adjustment that accompany a low-pressure economy, which could lead to hysteresis, are well documented. Training opportunities are provided with entry-level jobs and so the (average) skill of the labour force declines as vacancies fall.

New entrants are denied relevant skills (and socialisation associated with stable work patterns) and redundant workers face skill obsolescence.

Both groups need jobs in order to update and/or acquire relevant skills. Skill (experience) upgrading also occurs through mobility, which is restricted during a downturn.

The idea is that structural imbalance increases in a recession due to the cyclical labour market adjustments commonly observed in downturns, and decreases at higher levels of demand as the adjustments are reserved. Structural imbalance refers to the inability of the actual unemployed to present themselves as an effective excess supply.

[MORE COMING HERE]

|

Advanced material – Hysteresis and the Phillips Curve

In this box, we will learn that if there is hysteresis present in the labour market, then a long-run trade-off between inflation and the unemployment rate is possible even if the coefficient on the augmented term in the Phillips curve (the coefficient on the inflationary expectations term) is equal to unity. This result was shown in Mitchell, W.F. (1987) ‘NAIRU, Structural Imbalance and the Macroequilibrium Unemployment Rate’, Australian Economic Papers, 26(48), June, 101-118. At any point in time there might be an equilibrium unemployment rate, which is associated with price stability, in that it temporarily constrains the wage demands of the employed and balances the competing distributional claims on output. We might call this unemployment rate the macroequilibrium unemployment rate (MRU). The interaction between the actual and equilibrium unemployment rates has been termed the hysteresis effect. The significance of hysteresis, if it exists, is that the unemployment rate associated with stable prices, at any point in time should not be conceived of as a rigid non-inflationary constraint on expansionary macro policy. The equilibrium rate itself can be reduced by policies, which reduce the actual unemployment rate. Thus, we use the term MRU, as the non-inflationary unemployment rate, as distinct from the Monetarist concept of the NAIRU, to highlight the hysteresis mechanism. The idea is that structural imbalance increases in a recession due to the cyclical labour market adjustments commonly observed in downturns, and decreases at higher levels of demand as the adjustments are reserved. Structural imbalance refers to the inability of the actual unemployed to present themselves as an effective excess supply. In this sense, the MRU is distinguished from Friedman’s natural rate of unemployment, which was considered to be invariant to the economic cycle. To see how hysteresis alters the Phillips curve, we start with a standard wage inflation equation such as: which suggests that the rate of growth in money wages in time t (Wdot) is equal to some constant (α) which captures productivity growth and other influences, less the deviation of the unemployment rate from its steady-state value. The gap (Ut – U*t) is just a different way of capturing the excess demand in the labour market. If the gap is positive then the actual unemployment is above the MRU and there should be downward pressure on money wage demands, other things equal. If the gap is negative then the actual unemployment is below the MRU and there should be upward pressure on money wage demands, other things equal. We have made the sign on β negative to be explicit in the our understanding of how the state of the labour market impacts on money wages growth. This is, of-course entirely consistent with the original Phillips depiction. The additional term captures inflationary expectations as explain in our derivation of the EAPC. he hysteresis effect, that is, the tracking of the actual unemployment rate by the equilibrium rate of unemployment could be represented in a number of ways. In this example, we follow Mitchell (1987) who represented U* as a weighted average of the actual unemployment rate and the equilibrium rate in the last period. The following model shows that the MRU adjusts to the actual unemployment with a lag: This says that the current MRU (U*t) is equal to its value last period (U*t-1 plus some fraction of the gap between the actual and MRU last period. The value of λ measures the sensitivity of MRU to the state of activity. The higher is λ, other things equal, the greater the capacity of aggregate policy to permanently reduce unemployment without ever-accelerating inflation. [TO BE CONTINUED] |

Conclusion

This discussion will continue next week. I have noted the comments that suggest I could say all this in two or three sentences. Maybe I could but then it wouldn’t be educative but rather assertive.

If you understand the place this literature has in the overall debate you will realise the centrality of the arguments. Almost all the contemporary debates about policy intervention or not are, in one way or another, linked to the debate about inflation and unemployment.

Next week I will move into a braader discussion of conflict theories of inflation and supply-side (raw material) shocks. I will propose this is a general Modern Monetary Theory framework for understanding inflation.

Then we move onto how the Phillips curve can be rendered irrelevant through employment buffers.

I might also write a special box about the IMF intervention into Britain in 1975-77 because that was an important event and is mostly misunderstood. As a clue – it was totally unneecessary. But I will need to explain that given it is a contentious statement.

But then some of my readers would probably be happy with the one sentence dismissal of one of the more important historical eras in macroeconomics.

Saturday Quiz

The Saturday Quiz will be back again tomorrow. It will be of an appropriate order of difficulty (-:

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Bill, what you are describing about how unemployment leads to loss of skills and so a higher NAIRU tallies neatly with Steve R Walman’s latest post on interfluidity where he describes how so much of the accumulation of productive capacity (real world capital formation) is in the form of human expertise rather than in the form of machines and buildings (least of all financial assets). What I’m less sure about is whether a job guarantee could build such expertise relevant for the 21st century. To my mind what is needed is human ingenuity rather than brute labour. Our economy is becoming ever more automated. We don’t need vast armies of navies to dig canals. We need people to be able to spot what other people would pay for and to step into that role. That kind of expertise need not only be high tech or “elite”. It could be providing home help for elderly neighbors or whatever. To my mind allowing that to flourish could mean replacing mean tested benefits with a citizens dividend and not getting in the way at all. Especially having a tax system that leaves everyone with enough to pay for such services/goods. We basically now need geeky people to be free to start up ultra high tech businesses creating better automation, energy systems etc and everyone else to be free to provide human care for those who want it. There is not much future for production line workers unless our civilization goes backwards.

I’m looking forward to the future post you’ve just alluded to where you say you are going to tackle supply shocks and inflation/unemployment. My uneducated impression is that so called “supply shocks” so often are really the manifestation of currency exchange rates. Basically how the global supply of commodities are shared out between countries. I think this is at the root of so much tragic economic policy. A country will get a big slice of the global pie of commodity supply if it has a single minded focus on serving the short term moneyed interests. It leaves little scope for “enlightened self interest”.

The hysteresis idea has been challenged here:

http://www.econ.cam.ac.uk/cjeconf/delegates/webster.pdf

Also, I got the distinct impression during the 1970s that the wage price spiral, and consequent deflationary policies imposed by both Labour and Tory governments in the UK were caused by silly wage demands. That seems to be supported by the chart here:

http://stumblingandmumbling.typepad.com/stumbling_and_mumbling/2012/12/on-wage-and-profit-shares.html

Bill,

I think for the piece on the 70s it might be useful to have a time-line of events which affected prices and wages. This might include: the budget deficit, government policy changes, CB target rate movements, oil price changes, price changes and wage average wage changes etc. If these data actually exist then it might be possible to see more clearly the chain of cause and effect.

Kind Regards

Thanks for this open discussion.

As I read your draft, I relate to what I have observed over the years. Most recently, I observed wage demands drop dramatically compared to demands embodied in the previous contract. I attributed the drop to the observation that local unemployment was dramatically higher at negotiation time, projected inflation was lower, and stimulative policy seemed to be ineffective. An increase was still embodied for the next three years which was passed on to consumers in our monopolistic enterprise which is an electric utility.