It's Wednesday and we have discussion on a few topics today. The first relates to…

What comes after farce?

The expression “a descent into farce” is meant to describe a terminal condition – where things have become as ridiculous (or whatever pejorative term you desire) as they can get. I think the Euro elites are carving out new grounds that will require some new terminology. Their latest iteration – the second Cyprus bailout deal – is about as bad as it gets. You would think anyway. But given the capacity to outdo themselves with incompetence and sheer bastardry, I will await further developments before I consider the latest action to be the terminal condition. It almost beggars belief that highly paid and obviously self-important senior officials (such as the Dutch Finance Minister who is the head of the Eurogroup of Finance Ministers) could in one breath say one outlandlishly stupid remark to the media and then, in the next breath, repudiate that statement with another equally nonsensical statement that flies in the face of fact and practice. So if anyone out there wants to speculate on “What comes after farce?” please let us know. The problem is that as a slapstick comedy this rates among the best except in this case, millions are unemployed. But it goes further with the Cyprus fiasco – and the Dutchman’s hints of a new model forming. First, the unemployed and poor are bearing the risks of a failed capitalist economy. But now, the consumers are being forced to take losses. Where the hell are all the capitalists? Probably wining and dining with their Euro elite mates in Brussels.

A while ago – the next best thing in the Eurozone, which was going to solve the crisis – was the European Stability Mechanism (ESM). That has about €700 billion in its coffers and I understood was designed to rescue ailing Eurozone banks and prevent the necessary funds appearing as new debt on the books of the relevant member-state governments.

Well forget about that. The latest bailout – or bail-in model – as the jargon goes – is that in the Eurozone, the following behaviour will be observed. Private savers will trundle down to their friendly corner bank and open saving accounts as a way of risk managing their future.

At some point, due to the mismanagement of the bank managers (who are all paid massive incomes), or the mismanagement of the aggregate (monetary and fiscal) policy framework

The EU Observer reported yesterday (March 25, 2013) that – Euro chief spooks markets with Cyprus comments.

Apparently, the Dutch Finance minister, who chairs the Eurogroup (the Finance Ministers’ group) said after the Cyprus bailout was announced that it was a “template for future eurozone bank re-structurings”.

He was quoted as saying:

If there is a risk in a bank, our first question should be ‘Okay, what are you in the bank going to do about that? What can you do to recapitalise yourself? … If the bank can’t do it, then we’ll talk to the shareholders and the bondholders, we’ll ask them to contribute in recapitalising the bank, and if necessary the uninsured deposit holders …

So ultimately the model of capitalism that is evolving in the minds of these characters is one where not only a the risks privatised and the losses socialised but now a broader concept – the consumer pays for the losses of the company they deal with.

One of the concepts that students learn in introductory microeconomics is – consumer sovereignty. It is one of the key building blocks of the neo-classical claim that markets are efficient and guide resources to their highest value use.

Consumers reveal their preferences by “voting” with their dollars and know best. The concept informs a lot of policy design with respect to social transfers (in-kind are alleged to be inferior to cash etc).

As I noted the other day, studies in behavioural economics have shown fairly convincingly that consumers are not rational in the way economists think.

Daniel Kahneman (1994) assessed that the body of work in this field has demonstrated that:

… people are myopic in their decisions, may lack skill in predicting their future tastes, and can be led to erroneous choices by fallible memory and incorrect evaluation of past experiences.

[REFERENCE: Kahneman, D. (1994) ‘New Challenges to the Rationality Assumption’, Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics, 150/1, 18-36]

There is also the long-standing issue of supply-manipulation of the demand-side of markets – via advertising etc. The hard-core claim that advertising is just information which helps consumer sovereignty. The reality is nothing of the sort.

But the point is that the whole neo-classical economic model, which drives current policy, rests on propositions such as consumer sovereignty being a reliable description of how the markets work and what drives efficiency.

In that sense, it is extraordinary that the elites are now attacking the consumers that their “model” eulogises.

The practical import of the Finance Minister’s comments were that the financial markets dropped the Euro somewhat but the broader signal cannot be misunderstood.

Why would anyone who wanted to protect their savings invest in any Euro-denominated banks in nations that are vulnerable to economic misery?

In fact, why would anyone want to save in Euros per se.

I thought the argument presented in this Bloomberg Op Ed (March 26, 2013) – Cyprus Shows Trust in ECB Is Misplaced – went to th nub of the problem, even if the analysis was flawed.

The author challenges the statements made by the ECB last year that it would do anything that was required to save the European banking system. The Cyprus affair shows that the ECB is unwilling to fulfill its role as the central monetary authority.

It prefers to jeopardise financial stability to maintain its membership of the Troika, an ideological consortium of over-paid and largely unaccountable elites.

From a systemic perspective, Cyprus is tiny and the ECB would not blink if it recapitalised the capital-inadequate banks in one keystroke.

The preferred re-capitalisation, within the ambit of the Eurozone, would have been for the Cypriot government to have nationalised the banks and then for the ECB to ensure that the funds the government put into these banks were available. There are a number of ways this could have been done within the Lisbon rules.

Obviously, the better solution remains for the nation to exit the Eurozone and start using its currency sovereignty to restore health to a (nationalised) banking system. I will come back to that later.

As to the rescue-within-the-Eurozone approach, I thus disagree with the Bloomberg conclusion that the ECB doesn’t have the capacity to save the EMU.

The Bloomberg Op Ed says:

… the ECB can use to support euro-area countries is outright monetary transactions, the bond-buying program that it detailed in September. This facility has yet to be used, but its mere existence has caused borrowing costs for peripheral euro-area countries to fall significantly.

Thus recognising the capacity of the ECB to fix government debt yields at whatever level it sees fit.

But then, as if there is some logical connection, the Bloomberg Op Ed says:

Despite this renewed confidence in euro-area government debt, recent events in Cyprus have highlighted the bond-buying program’s limitations — it can alleviate stress in the sovereign-bond markets, but that’s about it. Even if Cyprus met all the conditions to use the facility, that wouldn’t help the country avoid a banking and economic collapse.

Which is a false conclusion. While the conditions for use of the OMT are ridiculous – that is, a nation has to be killing growth and jobs through fiscal austerity before it will be given help in this way – there is no doubt that the ECB could bankroll growth-supporting deficits if it so choosed.

Apparently the “investors should have seen the limitations of the ECB’s intervention tools before the Cyprus bailout disaster” because even though “sovereign borrowing costs have fallen” it remains the fact that:

… as the real economy is concerned, most indicators released from a euro-area country in the past six months have been worse than the last. This goes not just for the weak countries but also for core countries, such as Germany.

Which is not a statement about the capacity of the ECB. Rather it reflects on the ideology of the ECB and its role as part of the Troika. The Eurozone could have exited the downturn not long after it began if the ECB had have used its “fiscal” capacity correctly. The continued real contration is not because the ECB cannot stimulate the economy it is just that it won’t.

The conditions it places on the nations to maintain low bond yields are killing growth. It would be far better, given the deliberate absence of a credible fiscal authority in the EMU, for the ECB to tell the markets that it will fund any deficit as long as the deficits are creating employment and stimulating national income growth.

Beyond that point, the support would stop. Which is, of-course, just what a currency-issuing national government would do if its economy was in trouble. It would ensure that the deficit-spending was focused in areas most in need of demand stimulus. It would also ensure that its banking system was credible.

The ECB is operating in some sort of half-way house. It knows it has to operate in secondary markets to keep bond yields low and it knows it has to ensure banks have sufficient reserves. All functions that a sensible central bank would adopt as core business.

However, then it uses its obvious “fiscal capacity” to undo that monetary work. Illogical behaviour and only explainable once you realise that the ECB is an ideological player in the game.

The Bloomberg Op Ed then claimed that the ECB cannot reduce “political risk”:

Even if the ECB’s two special rescue mechanisms succeed in improving and stabilizing the financial and economic environment of a euro country in crisis, these tools are powerless to address political risk in the euro area. That’s a significant weakness, because political risk has repeatedly come to the forefront of this crisis, as elected politicians seek to protect their own country’s interests in negotiations over who will end up paying for the imbalances that have developed in a fundamentally flawed monetary union.

The political risk would dissipate to the normal to and fro of politics if unemployment was reduced, growth restored, pensions secured and bank deposits safe.

The political crisis that will continue to widen is all their own doing.

Anyway, after briefing the journalists about the Cyprus bail-in, sometime later in the day, maybe after a few more wines,this – Statement by the Eurogroup President on Cyprus – was issued.

Presumably this was after his mates realised the gaffe he had made in disclosing the discussions of the group to the media, and hence, the public:

Cyprus is a specific case with exceptional challenges which required the bail-in measures we have agreed upon yesterday.

Macro-economic adjustment programmes are tailor-made to the situation of the country concerned and no models or templates are used.

Which of-course was not only a humuliating about-face but also a bald-faced lie.

The nations are in trouble for two major reasons:

1. The uniform monetary policy (common interest rate) may not be optimal across all nations given how disparate their economies are. That is a popular view and is used to point out the fact that all the hot money surged into Spain and Ireland because interest rates were too low there.

I have some sympathy with that view but, in general, do not consider monetary policy to be an effective counter-stabilisation tool. When I say (above) that the ECB has the capacity to address the crisis I am not inferring this would come through interest rate adjustments. I am referring to its capacity as currency-issuer and the way it could fund government deficits. That is what I call its “fiscal capacity”.

It would be far better if that capacity was shared with a federal treasury institution but that it not likely to happen in the European context because it would require all nations, including Germany, to cede macro policy to a body, preferably elected by all of Europe as a federal government.

2. The lack of currency sovereignty and the fixed exchange rate constraints that membership of the Eurozone entails has been further exacerbated by the fiscal rules that are imposed on all nations by the Stability and Growth Pact and more recently by the Fiscal Compact mentality.

There is not a tailor-made macro policy for Greece, Germany etc. It remains that large economies such as Germany and France have violated the fiscal rules and pressured the authorities to turn a blind eye when seeking to apply the nonsensical Excessive Deficit Mechanism.

But what would be needed now is for the EU to allow nations such as Greece, Spain, Ireland, Portugal, Belgium, France, Italy etc to expand their deficits by several percentage points of GDP. The expansion required would be different in each case. That is what a “tailor-made” macroeconomic policy would look like.

What the Finance Minister was really saying is that the Troika reserves the right to dream up different ways of wrecking any specific nation, depending on what comes into the mind of the Germans, in between Wolfgang Schäuble’s Sudoku games.

There was an interesting 2011 paper published in the Cyprus Economic Policy Review – The Banking System in Cyprus: Time to Rethink the Business Model? – the author Constantinos Stephanou, being a Senior Financial Economist at the World Bank, who was at the time on secondment at the Financial Stability Board.

The paper noted that:

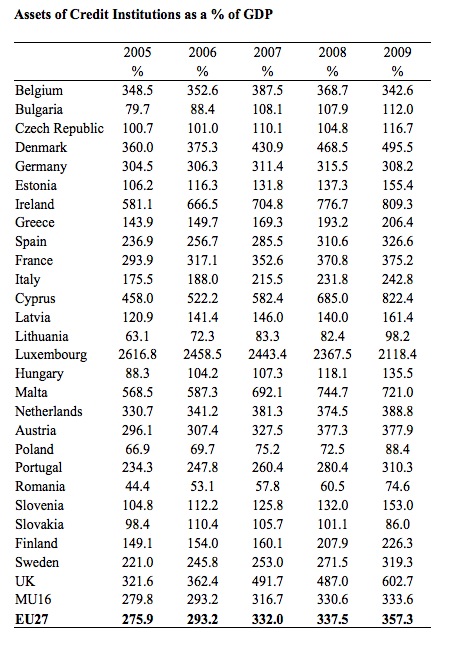

Cyprus has a large banking system compared to its economy (total assets of 896% of Gross Domestic Product or GDP in 2010), relative to the average for the EU and the Eurozone (357% and 334% respectively in 2009).

The ECB publishes its – EU Banking Structures 2010 – the last publication being in September 2010.

It provides detailed information about the size of banks and other interesting financial data.

The following Table is constructed using data in that publication and shows the total assets of credit institutions in Europe as a percentage of GDP (a measure of the size of the economy).

It is clear that since 2005 the size of the banking sector in Cyprus has grown rapidly but not all that differently to say the United Kingdom or Ireland.

And certainly, this growth was very evident at the time Cyprus joined the Eurozone in 2008.

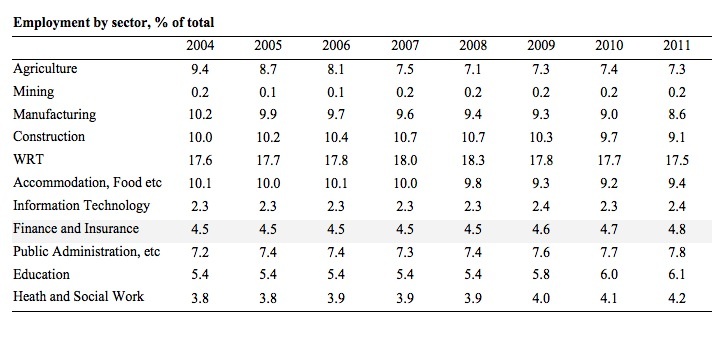

There has also been a lot of talk about the number of Cypriots employed in banking – as if almost all the population is in some way working in a bank.

The most recent detailed labour force statistics available from Cyprus are the – Labour Statistics 2011 – publication.

The following Table shows the proportions of employment by main industry sector in relation to total employment (WRT is wholesale and retail trade).

Finally, it is overwhelmingly obvious that Cyprus should not have entered the Eurozone in 2008 and should withdraw immediately. It had two things going for it in the last few years – a financial sector and tourism.

The former will be destroyed by the decisions taken yesterday. No-one in their right mind would seek to put their savings, much less their “laundered” cash, in a Cypriot bank after the actions by the Troika.

The other source of growth, given the government is unable to promote domestic growth because it is in the SGP straitjacket, is Tourism. But Tourism is an one of those activities that comes after food and the basics.

At present, there is negative growth in the Eurozone and that has persisted more or less for 5 years. This is not a short-lived downturn. This is a chronic stagnation engineered with skill by the Euro leaders.

Export (tourism) growth cannot hope to boom under these circumstances. The other option (the Iceland approach) would be to enjoy some relative price advantage via a depreciated currency to boost tourism. That option is also prevented under the Eurozone arrangement.

So Cyprus will now wallow in increasing stagnation. The young will seek to migrate to better lands (where?) and unemployment will continue to rise.

As I noted last week in the blog – Troika Technical Manual: How to wreck (another) country? – when it entered the Eurozone its unemployment rate was 3.7 per cent. Since then it has risen to around 12 per cent and will exceed 14 per cent by the end of this year.

The austerity that is now being imposed on it and the destruction of its banking sector will ensure that it keeps rising.

I know the responses will focus on the “costs” of depreciation. As I have noted several times in other cases, while it is certain the currency will depreciate, that process will be finite and involve real income losses for sure to the extent that people rely on imported goods and services.

But the lower exchange rate brings benefits to the export sectors – especially sensitive sectors such as Tourism. I have read in comments that this view is a neo-classical one and how is it that a Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) proponent would be spouting neo-classical dogma.

The idea that making something relatively cheaper boosts the willingness of people to purchase it is not the intellectual property of neo-classical economists. Yes, income effects typically dominate (which is something that is typically denied by neo-classicists) but relative price effects also operate. Yes, with lags. Yes, with less certainty than we might like. Yes, with distributional effects.

But it remains the fact that Cyprus would witness a boost in exports with a lower exchange rate of some quantum, whereas under current arrangements they have not way of tapping that unless they scorch the living standards of their workforce and even then, productivity growth would also slump and negate much of those relative price effects.

The most important point though is that the nation need not rely on net exports to get themselves out of the hole that joining the Euro created. With a fully sovereign government it could ensure its financial system is stable and pursue domestic policy initiatives to bring down its unemployment rate.

That has to be the best option for the nation now. Not painless by any means. Not somewhat fraught. But the path out of the mess is identifiable under the exit option and the tools known and available.

Under the status quo, there is no identifiable growth path and only a stagnant oblivion awaits them.

Conclusion

The unfolding nature of the crisis has been amazing to bear witness to. The ideological straitjacket that policy is operating in has forced the Euro leaders to innovate. The problem is that their innovations have gone from bad to worse.

They do not even understand their own logic.

Anyway, my train is about to reach Sydney so that will be it.

Greed of music promoters

Last night, I had tickets to the Sixto Rodriguez concert at the Enmore Theatre, in Sydney. The tickets were over $A80. I had been looking forward to the concert since December when we bought the tickets. He was a favourite of mine back in the early 1970s when he was obscure. I like these obscure geniuses!

Anyway, I arrived at the theatre in Sydney only to find out that the tickets were “standing room”. That is, the promoters these days rip out the seating in the theatre and cram as many people in as they can but still charge patrons the price that would normally elicit a seated position in the auditorium.

The night before I had seen Shuggie Otis (another obscure genius) in Melbourne at the wonderful Hamer Hall for the same sort of price and enjoyed a very comfortable seat with excellent sound.

So despite really wanting to see Rodriguez live I decided not to be herded like cattle by these greedy promoters. I disposed of the ticket and caught the train hometo Newcastle. I would recommend no-one goes to the Enmore Theatre in Sydney before checking that you actually are paying for a seat.

The standing room entry they were selling for $80 wasn’t worth $20.

CPSU Campaign to Protect Public Services

Despite my claims that I would be giving this presentation yesterday – in fact, the presentation is later today. There was a major mix-up in the respective diary entries.

Come along and give the union your support. Grass roots action is needed to change the direction of policy.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Dear Bill

You say that Cyprus should exit the eurozone. However, will that not result in losses for most depositors as well? Suppose that a Rusian has 250,000 in his account at a bank in Cyprus. Now Cyprus reintroduces its pound and those 250,000 euros will become 250,000 Cyprus pounds. If the pound then devaluates by 40%, the Russian ends up with only 150,000 euros. What matters to foreign depositors is the exchange rate, not the domestic inflation rate because they won’t be spending their money in Cyprus.

Regards. James

“If the pound then devaluates by 40%, the Russian ends up with only 150,000 euros.”

That’s the risk of investing in foreign jurisdictions. The exchange rate will fluctuate.

But those Cypriots internally with > 100K Euros would not lose out. The pound in their pocket would not change value.

A sovereign nation is there to look after its own citizens, not be a wealth manager for foreign savers. The Russian can sell those Cypriot Pounds to grateful Europeans who are then flocking to Cyprus to take the sun.

It seems that there is a lot of confusion about the external rate and the internal rate within a sovereign monetary area. MMT clearly explains that the external rate will fluctuate, and it is that degree of freedom that helps give the government extra policy space to manage the real economy.

As an example the external rate of the UK Pound has dropped by 25% since 2007. And yet internally we have barely noticed. It’s only when we look at foreign holidays that we see the effect.

That’s because despite the best efforts of our chancellor to stuff the economy up, the auto stabilisers have continued to function in a sovereign economy.

Neil, In principle I agree with you but it is a bit wider than holidays. I know someone who imports shoes to the UK. When the exchange rate changed, he waited over a year after the exchange rate shifted presuming it would revert. When it didn’t, he hiked the price up. We do see the effect on prices of imported goods and commodities but it trickles out slowly. UK had quite high inflation after 2008 considering that we might have been expected to have had deflation thanks to the crisis. That inflation was just a slow seepage of the exchange rate shift. To the extent that it pushes up imported raw material costs, it worsens the depression.

It’s clearly wrong, as Bill suggests, to impose haircuts on depositors which were not part of the agreement between depositors and banks when depositors first lodged their money. On the other hand, there is some logic in depositors who want their money loaned on or invested by their bank taking a hair cut when those investments go badly wrong.

The logic is that if that haircut is ruled out, there is then not a level playing field as between investment/loans done via a bank and investment/loans done via e.g. the stock exchange or a family investing in a small business out of the family’s savings.

To illustrate, if the haircut is ruled out and I deposit money in a bank and the bank lends to corporation A,B,C etc and it goes badly wrong, the taxpayer rescues me. On the other hand if I buy bonds in corporation A,B,C etc on the stock exchange and it goes badly wrong I’m on my own. Put another way, ruling out haircuts equals a subsidy of banks and depositors, and there is no excuse for that subsidy.

“UK had quite high inflation after 2008″

It wasn’t high at all.

It’s gone from 108.7 to 124.4 on the index – a rise of 14.4% over four years. The previous four years were from 98.6 to 108.7 – a rise of 10.2%. And the latter was a remarkably benign period.

So it barely registered and people adjusted to it over a long period of time. And, as Bill pointed out, it is a one off event.

Admittedly it was made easier by the fact that it was nothing more than a reversion of the unwarranted 33% increase in the UK pound in 1997/8.

” We do see the effect on prices of imported goods and commodities but it trickles out slowly.”

Which is precisely the point. The change is buffered over time allowing everything else in the economy to adjust slowly as well – including development of substitution products and services in the domestic market.

And that adjustment and accommodation would be more marked if the government was aware of the situation and was prepared to sustain the domestic economy along the MMT lines.

We’ve adjusted in a period where a rabid chancellor is deliberately trying to wreck the economy.

Dear Bill,

I am surprised by your criticism of the Dutch’s statement “[…] we’ll talk to the shareholders and the bondholders, we’ll ask them to contribute in recapitalising the bank, and if necessary the uninsured deposit holders […]”.

I don’t see anything wrong with this at all. Where do you draw the line between a deposit at a bank and a loan from an individual/corporation to a bank? The line is drawn at an arbitrary level of Eur100k which by most standards of people’s liquid savings should be more than adequate to not punish people who are not in the business of lending to banks. If a bank is deemed insolvent (i.e. tons of bad assets) creditors/equity holders in the following order should be wiped out: shareholders, subordinated bondholders, senior bondholders and uninsured depositors. This is the model that should have been applied to Ireland, not a bailout of all the former by the state. Insured depositors should be made whole if necessary.

I think this is commensurate with a risk/reward approach to private business while protecting those who, judged by their level of liquid deposits at a single bank, are not in the business of assessing the creditworthiness of the banks in which they deposit their savings.

So, I wonder where your criticism “the consumer pays for the losses of the company they deal with” comes from.

Regards

Javier

PS I also saw Robert Cray a few weeks ago (in London) and he was brilliant.

@Neil

You have summed up my problem with MMT.

It uses inflation to bail out the banks assets ………the fiat flows through their (control) systems.

We make them live another day to do yet more damage to our now probably short and brutish lives.

If you are a dead man walking anyway its time to introduce pure fiat into the system that will destroy the double entry banking theft.

PS Stone

British physical trade in detail is perhaps going into the secret files.

Top secret now. ?…………

“The MRETS publication has been discontinued. The associated (historical) dataset is still available as part of the UK Trade statistical bulletin and online time series.”

http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/uktrade/monthly-review-of-external-trade-statistics/january-2013/index.html

Figures.

There was a truly huge spike in silver imports reported in the final Dec edition – for 2012 in total distorting the UK trade figures massively.

For the record £ 6.052 billion of imports …..no 19 top import for 2012 !!!

If this is a proxy for Gold movements ????????????

Javier,

That is the system that we have at the moment. The question is whether that is an appropriate system for a stable economy.

The problem is that depositors fail to see themselves as investing in the bank. It is after all an illusion.

The state has made the decision that 100K is the level below which that illusion is maintained. Above that: caveat emptor.

The problem is that likely isn’t enough for any businesses that are trying to fund a reasonable payroll. And that means the 100K limit is forcing businesses to run their payroll on lines of credit rather than self-funded working capital. Is it appropriate to force a business to borrow from a bank because that’s the only way you have to push the money supply?

So what do we do? Is it sensible to increase the limit? Or do we fix the problem properly by shifting transaction management and deposits out of the private banks – essentially removing their ability to hold the country and individuals to ransom?

If we do the latter, then do we back fill the bank liabilities with central bank funds or force them to seek private funds?

There are lots of interesting trade offs in the design of a banking system.

Here some ideas for improving on the problems that Javier and Neil have identified.

First, while there are good arguments for giving depositors a hair cut when things go badly wrong (set out by me and Javier above), there are nevertheless depositors who DON’T WANT the risk of losing anything. Plus there are entities which are legally obliged to lodge clients’ money in a 100% safe manner (e.g. lawyers). Plus, I think access to a 100% safe account is a basic human right.

So . . why not offer those people 100% safe accounts? Their money would not be loaned on or invested (which is where the risk arises). Their money would just be lodged at the central bank, where it would earn no interest.

Second, as to those who want their money loaned on or invested, they can sod*ing well carry the associated risk: just like if they put their money into a stock market investment, they carry the risk.

Under the latter system, the Cyprus banking shambles just wouldn’t have happened. Indeed, it’s almost impossible for banks to fail under the above system. Re Cyprus, those wanting 100% safety would not have lost anything. As to the rest, they’d have got a haircut, but that would have been no more than they signed up for. Problem solved. Moreover, bank subsidies disappear under the above system. What more do you want?

Now there is a name for the above system: it’s called “full reserve banking”.

So I’d like to congratulate all and sundry – the EU, IMF, ECB, The Financial Times, and many others – for fumbling their way in a somewhat disorganised manner in the direction of full reserve.

@Dork of Cork

This is the justification the ONS gives.

“We no longer publish export figures with MTIC trade excluded as international legislation dictates this trade should be recorded. As such, we do not want export figures devoid of MTIC trade to appear in any publication. We accept that some users may want MTIC excluded from the exports statistics as it inflates economic activity. As the MTIC adjustment is published, it is easy for such users to make this adjustment themselves.”

An easy adjustment for the user to make. Really!! Nothing like making everything more transparent.

However Neil is correct with regard to UK internal systems & flows.

They are rebalancing without the savage deflation of the euro 9th circle.

http://www.rail-reg.gov.uk/server/show/ConWebDoc.11128

UK substitution of gas for coal is also the most dramatic example in Europe but their monetary situation calls into question their entire transport and energy focus.

Why is it investing in wind , in roads ? in houses ?

The Kings and Queens of Albion with a few notable exceptions have no interest in fiat power – they are happy to sit on their assets and watch the banks grow their wealth claims.

A true fiat King would have no interest in the trappings of wealth and would simply crush the banks with a full on military fiat regime

England is infact playing out the last act of a thousand year banking crisis.

The problem is of course they wish to drag the rest of us down with the ship.

Have to agree with several of the commenters. In this case I think the EU finally did something right. Wealthy investors insisting on speculative investments and then insisting that the state cover them when the investments blow up, was definitely a big part of what drove the financial crisis. I think the correct phrase was ‘privatizing the gains and socializing the losses’. And that is what needs to stop. Of course the investors in German Banks are guilty as well, but I don’t expect them to be taking a haircut any time soon.

Early in the crisis I read something about depositors in Cyprus’s banks receiving abnormally high rates of interest on time deposits. Is that true?

What comes after farce?

Doesn’t economics mirror history in reverse? It repeats itself, first as farce, then as tragedy.

Bill’s discussion of consumers raises questions about some of the double-think of modern financial capitalism. Ordinary small bank depositors think of themselves as consumers of a storage service. But in fact, they are creditors of a financial institution.

Still, I thought one of the principles of postwar financial stabilization was the insurance of small depositors by the monetary authority. Among the many problems that have been revealed about the problems with the EZ architecture, it looks like another one is that it’s small deposit insurance system is nation-based and not ECB-based.

Is old Richard fit for work ?

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_7ggl35-DI8

There is no reason why people can’t have secure accounts and interest, viz National Savings.

There is no reason why people can’t enjoy free transaction banking.

There is no reason why people should be denied reasonably access to a sensible priced mortgage.

You just have the lending banks effectively as agent of the central bank – paid for their loan underwriting skills and restricted to a narrow range of operations. Since the regulator is the major funder, the piper will play the tune they are told to play.

Should the risk capital be private or public in such a setup?

Not really getting why this is such a good thing.

Isn’t the banking system in Cyprus effectively finished as a result of this?

What comes after farce?

Why Force of course as in TINA – no choice given to Cypriots

Neil says, “There is no reason why people can’t have secure accounts and interest, viz National Savings.” Yes there is a reason, as follows.

The UK’s “National Savings” is NATIONALISED. There’s no limit to the goodies it can offer because it is subsidised by taxpayers. NS has accounts that offer a combination of interest and inflation proofing that commercial banks cannot match. So the amount deposited per person is limited. I know, because I’ve got such an account.

Second, if any commercial entity offers a secure account and interest, someone has to be subsidising it. Reason is that interest can only be earned by lending on or investing the relevant money. And lending / investing is not a 100% safe activity. So someone must be carrying the ultimate risk, and we all know who that is: the taxpayer.

“There is no reason why people can’t enjoy free transaction banking.” Same argument again. In other words if you want to throw taxpayers’ money at something, then ANYTHING can be made free. However it’s generally accepted in economics that GDP is maximised where prices align with costs – unless someone can prove overriding social reasons for a subsidy. There are strong arguments for subsidising health care and education for kids. As for bank accounts, I don’t know what the justification for a subsidy is. But I’m all ears.

But absent a subsidy, commercial banks normally just cannot offer free transaction accounts: especially if, as occurs under fractional reserve, they are prevented from investing money that is supposedly “instant access”.

Re Neil’s idea that commercial banks act as agents for the central bank, that’s what would actually happen with safe accounts under full reserve. William Hummel (who advocates full reserve) advocates that such accounts should actually be AT THE central bank. I think that’s too much paperwork for the central bank. But see Hummel’s arguments here:

http://wfhummel.cnchost.com/monetaryreform.html

Neil ends by asking whether the risk capital should be public or private. The answer is thus.

In the case of safe accounts, there is no “risk” worth talking about.

As to money that is loaned on or invested under full reserve, the entire risk is carried by private sector entities. The exact way that risk is split as between commercial banks and depositors varies a bit depending on which version of full reserve is involved (Laurence Kotlikoff’s version, William Hummel’s version or the version advocated by Positive Money, Richard Werner and the New Economics Foundation).

For some reason, most of the above, Ralph & Neill especially don’t or won’t get to the root cause

of the insolvency of the Banking System of Cyprus.

The Laiki Bank invested in Greek Sovereign Bonds, trusting that the ECB through the “stability mechanism”

would buy those bonds at par, should the need arise. Shortly after Greek Sovereign Bonds lost 70% of their

value, in a Troika engineered “restructuring”, Laiki booked a loss of 2.6 Billion Euros on it’s Greek Sovereign

Bond portfolio. It is extremely likely that Cyprus Bank, also booked significant losses on EU Sovereign Bonds, which were not supported by the ECB “stability mechanism” at all.

So far from making significant loans to shady enterprises, the bulk of the losses were in supposedly safe

financial instruments EU Sovereign Bonds. Those losses were the direct result of decisions made by the

Troika, which made a mockery of the ECB “stability mechanism”.

Were I Cyprus, I’d do the following:

1. Issue the Cypriot Pound at par with the Euro

2. Pass a law that forcibly converts all Cypriot financial instruments into Cypriot Pounds, including Cypriot Sovereign Bonds, deposits in Cypriot Banks, wages, prices, etal.

3. Institute a tort claim in the highest court of Cyprus against the ECB, the Troika, for the full amount of losses caused by their decisions to the Banks, Government, Citizens, and Depositors of Cyprus, in the amount of EUR 20 Billion, plus punitive damages of EUR 200 Billion.

4. Pass a law that allows the Government of Cyprus to seize any and all EU property to satisfy the pending judgement, immediately. This law also makes it a criminal offense to destroy the value of Sovereign bonds and this law would be used to charge the Troika, issue warrants for their arrest, and try them in absentia.

5. Using the suit and law, seize the British Bases on Cyprus. Seize the gas fields, the oil fields, and anything else not nailed down.

6. Make a deal with Putin, as follows:

a. SPER BANK takes the Russian Deposits, forming a branch in Cyprus

b. Cyprus passes a law prohibiting Russian Nationals from having bank accounts in Cyprus, except at

SPER BANK CYPRUS LTD

c. Cyprus passes a law which makes SPER BANK CYPRUS LTD. operative under Russian Law, which

means SPER BANK CYPRUS LTD, can and will report the ID of it’s depositors to the Russian Tax

Authorities, and the amount they have on deposit in Cyprus. This also means that Russia can impose

penalty witholding from accounts at SPER BANK CYPRUS LTD, to pay unmet tax obligations in

Russia.

d. Russia gets both bases for its exclusive use for 99 years.

e. Russia takes the seized stuff and disposes of it on behalf of Cyprus

I can assure you that if this is done, the Troika will never do this sort of thing again.

INDY

Yes, having Cyprus effectively declare war against the European Union regardless of who is and is not part of the monetary union will really show them. Perhaps Cyprus should also paint the sun blue so the troika have to shell out trillions painting it yellow again. That will teach them.

Off topic:

Bill, just saw this in the AFR and must say I was surprised:

JACOB GREBER Economics correspondent

The Gillard government’s class war rhetoric has been undermined by Productivity Commission research showing the nation’s richest 1 per cent are not responsible for widening inequality.

Analysis published by the commission on Wednesday argues Australians have benefited from average income growth over the past two decades of more than 3.5 per cent a year, one of the developed world’s highest rates.

In findings that reinforce the positive legacy of 1980s and 1990s labour market deregulation, the commission argues that much of the rising wealth has come through increased workforce participation, hours worked by part-time employers, and hourly wages.

At the same time, the study finds that Australia has one of the world’s most efficient systems of shifting wealth from the wealthy to the poor through government transfers and the tax system, a system that has helped keep a lid on rising inequality.

In the commission’s most controversial conclusion, it argues that the top 1 per cent of earners are having a lower impact on inequality than 20 years ago.

“Changes in income for this group are not overly accounting for the rise in measured labour income inequality,” commission researchers led by Jared Greenville wrote. “Rising inequality in Australia is also driven by the 99 per cent, not just the 1 per cent.”

The report shows that most of the increase over the past decade in income flowing to the top 1 per cent, or around 116,000 Australians, has gone to the self-employed, highlighting that entrepreneurs taking the biggest risks have secured the biggest wins.

The findings fly in the face of the government’s attacks on high-income earners, who pay significantly higher levels of tax, and come just days after former resources and tourism minister Martin Ferguson urged Labor to drop its “class warfare” and focus on governing for all Australians.

Mr Ferguson said last week that the class warfare rhetoric began in 2010 with the launch of the original mining tax and was “doing the Labor Party no good”.

The commission report shows that over the two decades since 1988-89, when the Hawke-Keating reform era was in full swing, around 75 per cent of the growth in real household earnings was generated by increased employment, longer working hours among part-time workers and increases in real wages.

“That is, between 1988-89 and 2009-10, more Australians joined the labour force, got jobs, worked longer hours and were paid more per hour,” the report states.

Most significantly, these developments have had a “moderating impact on measured household labour income inequality”.

In other words, while the wealthy have seen their incomes grow, so have the poorest households.

Average incomes rose 38 per cent over that period to around $1100 per week from $800 in today’s dollars.

So-called “equivalised” final household income, a measure that adds the impact of taxes, welfare payments and government services such as health, gained 64 per cent.

That is around twice the average gain of Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development nations over that period.

The Australian Financial Review

@Ralph

Never could get my head around the concept of taxpayers money

There is fiat (sadly , in its truest form no longer in existence as it is a killer of credit banks)

There is bank credit.

And there is commodity money.

All can be taxed.

Taxing is a action

Money is a thing ,a utility , albeit symbolic.

I am afraid credit banks generally destroy capital when they do what they do.

Consider the above hugely positive UK ORR rail stats.

Now look at Spain.

Tramway Jaen to be sold or folded ?

It would obviously save precious liquid fuel (to be burned elsewhere ?) but the present monetary system demands that it be burned.

At present euro cost the Spanish can still burn liquid fuel via idling cars in the center of Jaen and not pay for this labour. intensive system.

http://www.railwaygazette.com/news/urban-rail/single-view/view/jaen-light-rail-line-to-be-sold.html

Such is life

Such is death ….or is it debt ?

So for this to work they must find a company which can pay labour less.

But who will then pay the debt ?

Labour of course – if they sacrifice healthcare and high quality food.

Labour becomes less effective…….

Find more labour.

Destroy labour

Find MORE

Euro fiat is the darkest monetary spawn ever created.

Bill – there seems to be another element here at play.

Germany is preparing for elections in September 2013 before an electorate that is increasingly hostile to bailouts. Even though the German public may oppose the bailouts, it benefits immensely from what those bailouts preserve. Germany is heavily dependent on exports and the European Union is critical to those exports as a free trade zone. Although Germany also imports a great deal from the rest of the bloc, a break in the free trade zone would be catastrophic for the German economy. If all imports were cut along with exports, Germany would still be devastated because what it produces and exports and what it imports are very different things. Germany could not absorb all its production and would experience massive unemployment.

Currently, Germany’s unemployment rate is below 6 percent while Spain’s is above 25 percent. An exploding financial crisis would cut into consumption, which would particularly hurt an export-dependent country like Germany. Berlin’s posture through much of the European economic crisis has been to pretend it is about to stop providing assistance to other countries, but the fact is that doing so would inflict pain on Germany, too. Germany will make its threats and its voters will be upset, but in the end, the country will not be enjoying high employment if the crisis got out of hand. So the German game is to constantly threaten to let someone sink, while in the end doing whatever has to be done.

Cyprus was a place where Germany could show its willingness to get tough but didn’t carry any of the risks that would arise in pushing a country such as Spain too hard, for example. Cyprus’ economy was small enough and its problems unique enough that the rest of Europe could dismiss any measures taken against the country as a one-off. Here was a case where the German position appears enormously more powerful than usual. And in isolation, this is true — if we ignore the question of what conclusion the rest of Europe, and the world, draws from the treatment of Cyprus.

The more significant development was the fact that the European Union has now made it official policy, under certain circumstances, to encourage member states to seize depositors’ assets to pay for the stabilization of financial institutions. To put it simply, if you are a business, the safety of your money in a bank depends on the bank’s financial condition and the political considerations of the European Union. What had been a haven — no risk and minimal returns — now has minimal returns and unknown risks. Brussels’ emphasis that this was mostly Russian money is not assuring, either. More than just Russian money stands to be taken for the bailout fund if the new policy is approved. Moreover, the point of the global banking system is that money is safe wherever it is deposited. Europe has other money centers, like Luxembourg, where the financial system outstrips gross domestic product. There are no problems there right now, but as we have learned, the European Union is an uncertain place. If Russian deposits can be seized in Nicosia, why not American deposits in Luxembourg?

This was why it was so important to emphasize the potentially criminal nature of the Russian deposits and to downplay the effect on ordinary law-abiding Cypriots. Brussels has worked very hard to make the Cyprus case seem unique and non-replicable: Cyprus is small and its banking system attracted criminals, so the principle that deposits in banks are secure doesn’t necessarily apply there. The question, of course, is whether foreign depositors in European banks will accept that Cyprus was one of a kind. If they decide that it isn’t obvious, then foreign corporations — and even European corporations — could start pulling at least part of their cash out of European banks and putting it elsewhere. They can minimize the amount of cash on hand in Europe by shifting to non-European banks and transferring as needed. Those withdrawals, if they occur, could create a massive liquidity crisis in Europe. At the very least, every reasonable CFO will now assume that the risk in Europe has risen and that an eye needs to be kept on the financial health of institutions where they have deposits. In Europe, depositing money in a bank is no longer a no-brainer.

Now we must ask ourselves why the Germans would have created this risk. One answer is that they were confident they could convince depositors that Cyprus was one of a kind and not to be repeated. The other answer was that they had no choice. The first explanation was undermined March 25, when Eurogroup President Jeroen Dijsselbloem said that the model used in Cyprus could be used in future bank bailouts. Locked in by an electorate that does not fully understand Germany’s vulnerability, the German government decided it had to take a hard line on Cyprus regardless of risk. Or Germany may be preparing a new strategy for the management of the European financial crisis. The banking system in Europe is too big to salvage if it comes to a serious crisis. Any solution will involve the loss of depositors’ money. Contemplating that concept could lead to a run on banks that would trigger the crisis Europe fears. Solving a crisis and guaranteeing depositors may be seen as having impossible consequences. Setting the precedent in Cyprus has the advantage of not appearing to be a precedent.

“The Laiki Bank invested in Greek Sovereign Bonds”

The root cause then is not the ECB action but the fact that a lending bank is lending money to foreign governments rather than domestic businesses and homeowners.

Loans to a non-sovereign government are the same risk as lending to any other currency user. You have to capitalise the income stream or ensure you have sufficient collateral.

So that is a failure of risk management in the bank – believing in the Euro myth.

“As for bank accounts, I don’t know what the justification for a subsidy is.”

We all need one. Like we need a councils and roads. And the BBC.

The justification is simple. It is a common good. And I know that it would be much cheaper to provide the transaction service centrally as it would eliminate the duplication, as well as some truly awful Heath Robinson computer systems.

“As to money that is loaned on or invested under full reserve, the entire risk is carried by private sector entities.”

The problem is that the money is charged for twice. You have the bank charging their usual fee and then you have some wealthy person charging their risk fee.

Additionally the private sector entities can’t oversee the bank – as we’ve already seen in the financial collapse when most of the shareholders were institutions with all the data at their finger tips. They were too fragmented even then. Increasing the amount and number of investors just makes that problem worse.

Private sector oversight of banks is a Freetard wet dream. Reality however requires a much bigger brother with a tighter leash to stop constant disasters.

All that makes lending very expensive unnecessarily.

The reason is the distance from the central bank. Rather than money going from the central bank to the private bank for a fee and then into the hands of a productive business, you have the money going from the central bank into the pockets of the wealthy *for free* via excessive tax cuts and then onto banks and into the hands of productive business.

So it’s really a question of where you want your ‘taxpayers subsidy’ to go – into the hands of wealthy investors via excessive tax cuts, the redirection of the fee for central bank money and excessive risk premium on business lending, or to pay the interest of the savings of widows and orphans.

In other words: 1% or 99%.

@ Neil Wilson

“As an example the external rate of the UK Pound has dropped by 25% since 2007. And yet internally we have barely noticed. It’s only when we look at foreign holidays that we see the effect.”

What planet do you live on?

Since 2007, food is up 30%, Utilities 26%, Transport 27%, Education 47%. So your fantasy that the external rate of exchange has no impact on what we have experienced internally, is just that, a fantasy.

Neil,

You’re all over the place.

You justify bank subsidies on the grounds that “We all need one. Like we need a councils and roads.”

The fact that something is essential is not generally accepted in economics as justifying a subsidy. Water, gas, electricity and food are all charted to customers at a price that covers costs. And . . . this is hilarious . . . ROADS are charged for in a way that covers costs: certainly if you include fuel duty.

Next you claim bank accounts are a “common good”. Nonsense. Air is a common good: hence the justification for clean air acts. No one can do without air. But as to bank accounts, some people don’t have bank accounts!

Next you say it would be “cheaper to provide the transaction service centrally as it would eliminate the duplication”. Well the PARTS OF the banking system which it pays do administer in a “central” fashion are already so administered: specifically the “end of the day” settling up system at central banks. As to the suggestion (if this is what you are suggesting) that there are economies of scale to be reaped from amalgamating the already too large banks, Andy Haldane has shown that that’s not the case. And in anyway, what’s that got to do with subsidies? The question as to whether there is a justification of a subsidy is quite separate from the question as to how much centralisation one should do or what economies of scale can be reaped.

“You’re all over the place.”

No I’m in one place. I’m with the 99%. You’re with the 1%.

Suggesting that you should charge granny for the bank account she has her state pension paid into and rob her of the little interest she earns so you can stuff public money into the pocket of the wealthy is beyond the pale.

It is disgusting.

“o your fantasy that the external rate of exchange has no impact on what we have experienced internally, is just that, a fantasy.”

I didn’t say no impact. I said ‘barely noticed’.

People are still going to work, and things are bubbling along. The average rate of change of prices is what I quoted – which means across the economy as a whole that is what has happened.

As ever if you disaggregate then some hurt more than others by the price change.

At a macro level there hasn’t been widespread dislocation or failure. The system has adapted to the new reality and people have absorbed what is a real reduction in the standard of living (given the lack of wage rises to compensate).

The buffering could have been better handled and the pain redistributed around better. But the important point is that there was no cascade failure in the economic system.

@ Neil wilson

“The average rate of change of prices is what I quoted – which means across the economy as a whole that is what has happened.”

Have you actually looked at the weights in CPI?

Food is 12%, housing and utilities are 12%, transport is 16%, so a total of 40% – when for people I know on median wage, those would be closer to 80% of disposable income.

Then we have recreation at 15% and restaurants and hotels at 14% – what a joke when people have little income left after the basics.

The CPI weights are total rubbish in the current environment when the average person is experiencing inflation way in excess of the supposed CPI average.

“The CPI weights are total rubbish in the current environment when the average person is experiencing inflation way in excess of the supposed CPI average.”

The weights come from the household expenditure component of the UK National Accounts and are reviewed annually by the ONS.

It may not fit your prejudice, but those weightings are based on hard data and are statistically sound. The change in spending patterns are taken into account as detailed in extensive document on the subject on the ONS site: http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/cpi/cpi-and-rpi-index–updating-weights/updating-weights–2012/index.html

It’s another example of the aggregate not fitting what you ‘feel’ to be the case – which is half the problem with macroeconomics.

There is quite a few studies about the difference between perceived price changes and actual price changes. It’s a known effect. But it is an illusion.

@Neil Wilson

So you believe that CPI weights that are partially based on what tourists spend their money on, give an accurate reflection of the impact of inflation on an average UK citizen?

I suggest you have a look at the Living Costs and Food Survey (based on 5690 households of the over 26m in the UK) that is used to set CPI weight. You can get a breakdown by income level. At the lower income levels, spending on food, drink , housing, utilities consumes 43% of household expenditure, but has only 30% weighting in CPI. With those all inflating at double the rate of the remaining categories since 2007, it makes a significant difference to the inflation that people at those income levels have experienced. Now I don’t know about you, but I am more concerned about what impact has been felt by the poorest in our society, not just those who feel it when they go their overseas holiday (A note for you, not everyone can afford those..)

And at the higher income levels they will spend less as a proportion of income.

As I said if you disaggregate then some are affected more than others. And as I said the distributional impact could have been better handled (in fact you’d struggle to handle it worse). As I said it was pay back for an unwarranted 33% rise in the value of the pound in 1998.

But that doesn’t affect the overall average for the average household.

The aggregate statistics are sound.

The aggregate statistics are sound, but I’m surprised at how cold you sound Neil. I didn’t think you were like that.