During the recent inflationary episode, the RBA relentlessly pursued the argument that they had to…

Structural deficits – the great con job!

There has been a lot of talk lately about the need for the Government to plot a course over the coming years back into fiscal surplus. Our perceptions of fiscal responsibility are being conditioned by the relentless media campaign that this is the best thing for the Government to do. We are being told that cyclical deficits are unavoidable at this time but the “structure of the budget” should point us back to surplus as soon as possible. This campaign is being supported by official looking documents that are produced by Treasury (notably the Budget papers) which have all sorts of technical terms in them that only the cognoscenti understand. The term structural deficit is being touted around in these documents and appearing in the opinion columns. But the way this concept is being represented is very misleading and is deliberately being used to obfuscate the lack of intention by this Government to seriously pursue full employment. Well lucky for me I am part of the cognoscenti and cannot be so easily fooled. Here is the truth.

The federal budget balance is the difference between total federal revenue and total federal outlays. So if total revenue is greater than outlays, the budget is in surplus and vice versa. It is a simple matter of accounting with no theory involved. However, the budget balance is used by all and sundry to indicate the fiscal stance of the government.

So if the budget is in surplus we conclude that the fiscal impact of government is contractionary (withdrawing net spending) and if the budget is in deficit we say the fiscal impact expansionary (adding net spending).

However, the complication is that we cannot then conclude that changes in the fiscal impact reflect discretionary policy changes. The reason for this uncertainty is that there are automatic stabilisers operating. To see this, the most simple model of the budget balance we might think of can be written as:

Budget Balance = Revenue – Spending.

Budget Balance = (Tax Revenue + Other Revenue) – (Welfare Payments + Other Spending)

We know that Tax Revenue and Welfare Payments move inversely with respect to each other, with the latter rising when GDP growth falls and the former rises with GDP growth. These components of the Budget Balance are the so-called automatic stabilisers

In other words, without any discretionary policy changes, the Budget Balance will vary over the course of the business cycle. When the economy is weak – tax revenue falls and welfare payments rise and so the Budget Balance moves towards deficit (or an increasing deficit). When the economy is stronger – tax revenue rises and welfare payments fall and the Budget Balance becomes increasingly positive. Automatic stabilisers attenuate the amplitude in the business cycle by expanding the budget in a recession and contracting it in a boom.

So just because the budget goes into deficit doesn’t allow us to conclude that the Government has suddenly become of an expansionary mind. In other words, the presence of automatic stabilisers make it hard to discern whether the fiscal policy stance (chosen by the government) is contractionary or expansionary at any particular point in time.

To overcome this uncertainty, economists devised what used to be called the Full Employment or High Employment Budget. In more recent times, this concept is now called the Structural Balance. The change in nomenclature is very telling because it occurred over the period that neo-liberal governments began to abandon their commitments to maintaining full employment and instead decided to use unemployment as a policy tool to discipline inflation. I will come back to this later.

The Full Employment Budget Balance was a hypothetical construct of the budget balance that would be realised if the economy was operating at potential or full employment. In other words, calibrating the budget position (and the underlying budget parameters) against some fixed point (full capacity) eliminated the cyclical component – the swings in activity around full employment.

So a full employment budget would be balanced if total outlays and total revenue were equal when the economy was operating at total capacity. If the budget was in surplus at full capacity, then we would conclude that the discretionary structure of the budget was contractionary and vice versa if the budget was in deficit at full capacity.

The calculation of the structural deficit spawned a bit of an industry in the past with lots of complex issues relating to adjustments for inflation, terms of trade effects, changes in interest rates and more.

Much of the debate centred on how to compute the unobserved full employment point in the economy. There were a plethora of methods used in the period of true full employment in the 1960s. All of them had issues but like all empirical work – it was a dirty science – relying on assumptions and simplifications. But that is the nature of the applied economist’s life.

Things changed in the 1970s and beyond. At the time that governments abandoned their commitment to full employment (as unemployment rise), the concept of the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (the NAIRU) entered the debate – see my blogs – The dreaded NAIRU is still about and Redefing full employment … again!.

The NAIRU became a central plank in the front-line attack on the use of discretionary fiscal policy by governments. It was argued, erroneously, that full employment did not mean the state where there were enough jobs to satisfy the preferences of the available workforce. Instead full employment occurred when the unemployment rate was at the level where inflation was stable.

NAIRU theorists then invented a number of spurious reasons (all empirically unsound) to justify steadily ratcheting the estimate of this (unobservable) inflation-stable unemployment rate upwards. So in the late 1980s, economists were claiming it was around 8 per cent. Now they claim it is around 5 per cent. The NAIRU has been severely discredited as an operational concept but it still exerts a very powerful influence on the policy debate. In Australia, it dominates the Treasury and the Reserve Bank modelling.

Further, governments became captive to the idea that if they tried to get the unemployment rate below the NAIRU using expansionary policy then they would just cause inflation. I won’t go into all the errors that occurred in this reasoning. My latest book – Full Employment Abandoned with Joan Muysken is all about this period.

Now I mentioned the NAIRU because it has been widely used to define full capacity utilisation. If the economy is running an unemployment equal to the estimated NAIRU then these clowns concluded that the economy is at full capacity. Of-course, they kept changing their estimates of the NAIRU which were in turn accompanied by huge standard errors. These error bands in the estimates meant their calculated NAIRUs might vary between 3 and 13 per cent in some studies which made the concept useless for policy purposes.

But they still persist in using it because it carries the ideological weight – the neo-liberal attack on government intervention.

So they changed the name from Full Employment Budget Balance to Structural Balance to avoid the connotations of the past that full capacity arose when there were enough jobs for all those who wanted to work at the current wage levels. People will seek more chances to save. Now you will only read about structural balances.

And to make matters worse, they now estimate the structural balance by basing it on the NAIRU or some derivation of it – which is, in turn, estimated using very spurious models. This allows them to compute the tax and spending that would occur at this so-called full employment point. But it severely underestimates the tax revenue and overestimates the spending and thus concludes the structural balance is more in deficit (less in surplus) than it actually is.

They thus systematically understate the degree of discretionary contraction coming from fiscal policy.

So they are trying to tell us that the business cycle moves around a fixed point – currently around 5 per cent unemployment – and above that the economy is operating with spare capacity and below it the economy is operating over full capacity.

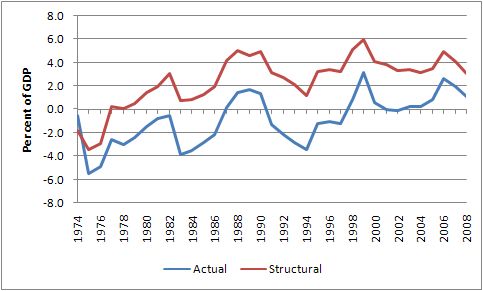

As a consequence you get the following graph which appeared in Budget Statement 4: Assessing the Sustainability of the Budget:

This is an example of the decomposition of the federal budget balance into cyclical and structural factors. According to the Treasury:

Based on these estimates, the structural budget balance deteriorated from 2002-03, moving into structural deficit in 2006-07. This shows that the actual underlying cash balances in previous years were primarily the result of the strength in Australia’s terms of trade, which increased by almost 40 per cent over this period. While the temporary fiscal stimulus measures result in a widening of the structural deficit, the deficit narrows over the medium term reflecting savings measures and the Government’s commitment to reduce spending as the economy recovers.

What they are saying is that the surpluses in the recent years were not structural but were driven by cyclical factors – the booming commodities prices. They are also saying that the underlying or structural budget has gone into deficit due to the discretionary changes of the Federal Government (the stimulus packages) and that by 2015-2116, the structural balance will be back in surplus. The falling deficit is projected on the basis of discretionary decisions made by the government to reduce outlays over this period.

But of-course, given the earlier discussion, this is all dependent on what you call “full capacity”. I define full employment as an economy that delivers as many jobs as their are people wanting them and hours of work consistent with the desired hours of the workers. In other words, an economy that has an unemployment rate around 2 per cent and zero underemployment. That is a far cry from the “full capacity” dodges used by the OECD, the IMF and the Australian Treasury. Their conceptions of full capacity are ideologically-loaded by the NAIRU concept and are frankly … a total joke.

So I thought I might just quickly estimate the structural balance based on an unemployment rate of 2 per cent. For simplicity I am ignoring the fact that increasingly those in employment are experiencing underemployment. Remember to be counted as employed you only have to work 1 hour per week. More workers are reporting they are being forced into part-time hours but want to work longer. So by ignoring this problem my estimates are significantly underestimating the full capacity position of the economy and will underestimate any structural surpluses that I calculate. Bear that in mind.

The steps in the calculation were:

- Compute Potential GDP by calculating the level of employment for each quarter if the unemployment rate = 2 per cent and ignoring labour participation changes (participation would be higher if the employment levels were higher). Then I computed actual labour productivity in persons and used the potential employment series to estimate what GDP would in each quarter at full capacity.

- I then estimated some regressions to compute the cyclical revenue and spending elasticities. In particular, I estimated an equation for tax revenue (a part of total revenue) and an equation for welfare and social spending (a part of total spending). They were regressed on the GDP gap in percentage terms in log form to estimate how sensitive these components of the budget were to deviations in the business cycle. I could have done this in a more detailed manner by estimating elasticities for different tax components etc but when I compared by outcomes with the estimates used by the IMF and the OECD they were fairly close. In fact, I could have saved myself time and just used their elasticity estimates without changing the results.

- I then used the cyclical elasticities to estimate the structural revenue and outlays (so T(s) = T*(%Output Gap)^elasticity and the same for outlays). I added the cyclically sensitive components of outlays and revenue back into total outlays and revenue and derived the Operating (cash) position. I simplified by not taking into account the recent shift to accruals for the operating result. Again this will not alter the result much.

- I also smoothed out the GST effect in the official data – again this doesn’t make any difference to the overall results – it just eliminates a big spike in the data around July 2001. Further, some missing observations in the official data were just interpolated (2 quarters) – with no major impact on the conclusions.

- This is deliberately simple but the conclusions are not dependent on the simplified approach I took.

The following graph shows you the actual operating results (Total Revenue minus Total Spending) since 1974 and the structural operating balance (computed as above). The difference between the structural and the actual reflects the fact that over this period the economy has never operated at 2 per cent unemployment. The difference between this estimate of the structural balance and the Treasury’s estimate lies in the fact that they are assessing full capacity at a much higher unemployment rate – which is not the full employment level of the economy.

So the Treasury estimates of the structural balance build in the assumption that the Government will not achieve anything remotely like full employment over the period shown in the graph. By the time the graph is crossing the zero line again (in several years) the economy will be at the NAIRU or around 5 per cent unemployment. That is not admitted in any of these public documents nor by the journalists.

The Australian econmics editor, Michael Stutchbury used this same Treasury graph above earlier this week in his Swan’s surplus of silence article and did not tell his readers about this underlying bias in the calculations. He should have because it would have influenced the way his readers interpreted and judged his article. They would have thought it a poor piece of journalism if they knew the basis of the discussion.

If you examine my graph you can see the actual balance (blue line) is well below the estimated structural balance (red line). The Federal Government has been running contractionary budget positions (structurally) since 1976. So the deficits over the period (1974 to 2008) are entirely cyclical and reflect the fact that rising unemployment drove the automatic stabilisers sufficiently against the contractionary bias in the budget to generate the deficits.

You can also see that the budget surpluses in the recent years were structural. They were not driven by the commodity prices alone as the Treasury is trying to tell us. The previous federal regime was running hugely contractionary positions during this time and relying on the private credit binge for growth. This was an unsustainable growth strategy and the height of fiscal irresponsibility. We are suffering the consequences of it now.

It should also be apparent that the swing in net spending (from the structural surpluses) to a structural deficit (which will be required for sustainability to finance private net savings) will be huge. That is, if we seriously consider full capacity to be when every one has a job!

What this tells me is that budget deficit currently is way to small as a percentage of GDP. The structural budget that the Government is coming from was very contractionary.

While this exercise is simplified (to fit it into a quick blog) all the additional complexities that I might have put into the estimation of the structural budget balance would not really change much. The diference between my estimates and the Treasury’s (and the IMF and the OECD) lies in my assumption that full capacity = full employment = every one has a job who wants one at the current wage levels.

They try to con us by equating the full capacity position with the NAIRU (currently estimated – read “made up” – by the Treasury to be just over 5 per cent). Commentators will then start raving on that the budget is too expansionary when in fact it will likely still be contractionary.

Spread the word!

You will get deficits anyway

I was asked last night during a lecture I gave in Newcastle about the financial crisis whether the previous surpluses would have occurred if the household sector had not loaded up on debt as much. The clear answer is that Costello may have got away with one or two surpluses but eventually the fiscal drag would have been so great that automatic stabilisers would have sent the budget back into deficit with rising unemployment and falling output growth.

Randy Wray made the point that in the history of the US, every time the federal budget has been in surplus, a major economic downturn followed immediately and sustainable growth was only resumed once the budget returned to deficit.

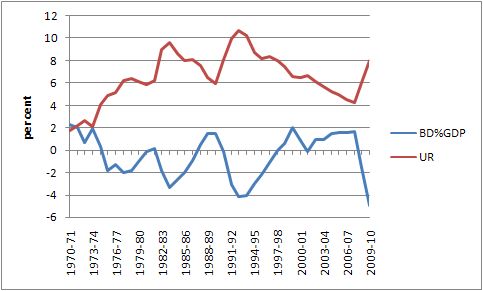

Consider this graph. It shows the recent history of the Federal budget (in Australia) as a percentage of GDP (deficits – and surpluses +) and the official unemployment rate. If you ever wanted a mirror image here it is. Every time we have gone into surplus over this period, rising unemployment has followed. The recent surpluses lasted longer because for a time the spending gap was partially filled by the private debt binge. That was not a sustainable growth strategy and it has now unwound well and truly.

The point: you will get deficits whichever way you go. It is far better to have structural deficits and underwrite strong employment growth and low unemployment than to try to pursue surpluses and create the conditions where the cyclical swings (the automatic stabilisers) drag you back into deficit but in this case with high unemployment and falling employment growth. It is a no-brainer that the Government and most of the rest (politicians and commentators) don’t seem to understand.

Spread the word!

Saturday Quiz tomorrow!

The Saturday Quiz will be available tomorrow late afternoon some time.

Dear Bill,

this posting now clarifies much better the query I had a couple of blogs ago (see copy below) regarding the causation.

Fascinating, and your explanation is crystal clear.

Thanks

Graham

#

graham says:

Thursday, May 14, 2009 at 8:17

Dear Bill, Alan and Lefty,

my query was just about the causation. Yes, I think I understood the matter of the national accounting. It is that in this instance of the business cycle, it seemed to me, that because on aggregate people had gone into such high levels of debt ( for whatever reason) that this inadvertently shored up the economy to such an extent that it was easy for Costello to run up a surplus as a result. If people had not run up such a debt and Costello had run a surplus then there would have been a major problem anyway, presumably much earlier than this current one, with people having a large deficit or drop in personal savings in order to prop up the surplus. In short the impression is that it wasn’t the surplus that CAUSED people to use credit to fuel growth but the other way around in this particular case where the credit only put off the pain until later (now).

Cheers

Graham

#

bill says:

Thursday, May 14, 2009 at 9:39

Dear Graham

The causation runs both ways because the budget balance is endogenous – that is determined by the system but also determining for the system. But the important starting point in understanding this stuff is to realise that the macroeconomic constraint is binding on individual choices. So when the Government runs a surplus it has to force the non-government sector to run a deficit. That is the constraint. So in net terms the non-government sector is running down wealth even if within it some individuals may be building personal wealth. The non-government debt did allow the economy to grow while the government fiscal drag was increasing which was, in turn, assisted by the debt-driven growth. It is clear that if the private sector had have tried to save early on as the surpluses were being accumulated that the whole show would have collapsed earlier than it has.

But it remains true that the intentions of the federal government of the day to pursue surpluses initially squeezed the non-government sector and forced the latter (as a whole) into deficit.

best wishes

bill

Bill, are you able to reproduce the BD%GDP/UR graph going from present day right back through the Keynsisan period, so as to give a visual demonstration of the fairly stark difference between now and then?

cheers

Dear Lefty

I will work on it. It is quite hard to get comparable data way back but I will see. It looks quite different to now – almost always in deficits – fairly small as a percentage of GDP and not as much oscillation as there is now. The surplus then crash dynamic entered the Australian scene in the early 1970s but was profoundly seen during the late 1980s and then now.

best wishes

bill

Hi Bill

As this is my first post to your blog I should say thanks for all your work on this issue. I’m glad someone is researching and still pushing for full employment.

I was born in 1960 and I recall full employment. I remember it in the late 60’s as conversations between my mum and others over afternoon tea which often went: ‘Such and such is leaving school and he has three jobs to choose from’. Those were the days! I’m sure a lot of others my age remember that and would be open to a push back in that direction.

The big difference between this recession and the one we had to have is the internet. I am one of the 200,000 or so who have lost their jobs since about September 2008. As a single person, I am quickly going broke. The newly unemployed include a lot of professional, intelligent and articulate people who will not go under quietly. What we need to do to get organised.

When the wider community learns of the impact of the waiting periods for Newstart Allowance, and the punitive income test rates for Newstart recipients, there will be widespread disapproval. These policies are accelerating the process of newly unemployed workers going broke. I believe there is going to be a mini revolt against government policy on these matters soon, and the government will be shamed into action. And I will be pushing your scheme as another policy response. Rising unemployment creates the opportunity to push the full employment agenda and its benefits.

Re the obsession of the media with the debt and deficit issues. In reading the papers today and since the Budget, I sense genuine alarm on the part of these commentators, not just about the debts and deficits per se, but about the competence of the government. The government (and the media) has ignored the newly unemployed so far, but the media will wake up soon and it won’t take long before unemployment is the main issue in the newspapers. With this will come a good opportunity to propose policy responses like the JG and force the government to answer the question: Why not?

I think the trick is to come up with a way of selling the JG concept so that even the monetarists can’t dispute the logic or the benefits. People power and the internet could produce the pressure needed to get your proposals seriously considered by the government.

By the way, was there anything you saw in the budget papers that states what 8.5% unemployment is in terms of the body count? If not, what is the approximate number?

Also, how much would it cost to implement your JG proposal?

Dear Collatoral Damage

Thanks for your interesting comment. It is a pity though that the professional ranks have to experience unemployment before they are prepared to do anything about it.

At at unemployment rate of 8.5 per cent there would be about 980 thousand (seasonally adjusted) people unemployment a few more next year if the labour force grows over the next 12 months.

The last time we costed the JG (May 2008) it would have required 557,000 full-time equivalent jobs to get the unemployment rate down to 2 per cent and wipe out underemployment. That would have cost $8.3 billion over 12 months with 80 per cent of the workers in the JG and the other 20 per cent in the private sector who responded positively to the stimulus.

best wishes

bill

Thanks Bill

If unemployment does rise to 980,000 that’s about 500,000 new unemployed since about the middle of 2008. The government reckons it will save 200,000 jobs with its infrastructure spending, but it does not admit that these 500,000 people (not counting the 450,000 previously unemployed) are thrown on to the scrapheap for several years. I wonder what the true cost of this is to the economy and the budget over time – it would be huge. It’s sad to think that this could have been avoided by spending a fraction of what the government has spent in cash splashes and infrastructure projects. But as unemployment worsens, the government will be forced into doing something. I think there would be broad support for a scheme like yours in the community, so don’t give up hope.

Dear Bill,

Thanks for your blog, I have been reading it lately with great interest, and i admire your advocacy of full employment.

That said, isn’t there a chance that you are looking over the real difficulties that governments face when trying to carry out expansionary Keynesian policy, in a highly integrated and competitive global economy? In general does this globalised context not force policy in neo-liberal directions, where the focus is on ensuring supply-side cost cutting, to maintain competiveness, rather than priming the pump with expansionary deficits? Surely it is not only a neo-liberal ideological conspiracy that has led both governments the world over – both liberal and left/labour – to move in free market directions.

What about the historical experience of labour/left governments such as British labour in the 1970s and Mitterand in France? Their attempts at running large deficits, to maintain full employment, lead to a devaluing of their currencies, and rising interest’s rates, due to the financial markets fear of inflation. The result was low growth and unemployment at similar levels to those seen under more strident neo-liberal regimes (Thatcher, Regan etc).The fear of inflation, it should be added, was not entirely irrational, given that especially in the context of low profitability (as has been the case since the 1970s) deficit fuelled expansion, led employers to lift prices, and increased wage earners bargaining power, leading to a wage-price spiral.

Sweden is one country that has over the last 30 years been able to maintain low unemployment, however, it should be noted that this has come at a cost. Middle-class wage earners have has to be prepared to tolerate a much slower growth in real wages (due to high taxation levels) in order to spread the burden of lower overall growth. They have achieved this through the powerful position of the unions, and also a high degree of social solidarity. Still, it has been costly for many, and indeed, is under severe attack from neo-liberals who are slowly trying to unravel this collectivist tradition.

Cheers,

Johnny R

Jonathan’s mentioning of the 1970’s situation brings me to a question.

What the the cause of the 1970’s stagflation?

Without knowing more, it would appear to me to have been primarily driven by the oil shock. With supply deliberately physically constrained, there was actual rationing of petroleum. The shock to such a critical driver of economic activity – transportation energy – would have had the perverse effect of both forcing recession and rising unemployment, while at the same time, the seriously constrained supply of such a non-discretionary commodity would have driven the price sky high (I’m sure I remember seeing historical oil price graphs that showed it did just that) which would have then flowed through the price of everything else, driving inflation and unemployment together, rendering the Phillips curve model inapplicable to this particular situation.

The newly emerging neo-liberals – sidelined for decades by Keynesianism – no doubt saw their chance to blame government intervention in the market as the cause, or at least to claim that their model would overcome these problems, and the rest is history.

What do you think Bill?

This article – http://www.nytimes.com/2009/05/14/business/global/14frugal.html?em – claims that Norway is thriving while running an 11% budget surplus. Why hasn’t it’s economy run down?

Or does Norway already have a full-employment policy?

Dear Lefty

Read the article carefully. They are getting a huge external boost from their energy net exports. That injection allows them to run high levels of employment with strong public services while running a budget surplus. It all comes down to the sectoral balances. In general, countries do not enjoy that level of net export boost. So they have to underwrite domestic saving with budget deficits to enjoy high employment levels. For a short time in Norway’s history they can do it via net exports. When that revenue dries up they will have to run deficits (after running their sovereign fund down) to sustain their very high standard of living. That is there future.

best wishes

bill

Dear Jonathan

Thanks for your thoughts. In fact, in a flexible exchange rate economy with free capital flows, there are less constraints on fiscal policy than if we were trying to run an old fixed exchange rate regime with a gold standard. I know a lot of progressive thinkers are harking back to those days and thinking it was these external institutions which made the difference. As I have explained in the past, fixed exchange rates tied monetary policy to defending the parity and forced the domestic economy to adjust up and down to current account pressures. Chronic deficit countries were always suffering deflationary biases (and rising unemployment) because of the need to defend the parity.

So given that is the case, I think the constraints imposed by neo-liberalism are entirely ideological and came about from a concerted campaign to win the battle of ideas. There is nothing about deficits that should frighten international capital. In fact, capitalists will make higher profits in a fully employed economy than in a stagnant economy.

The point you make about Britain and France in the 1970s applies to a fixed exchange rate world. It does not apply to flexible exchange rates. The reason their currencies devalued was that the central banks could no longer defend them (inadequate foreign reserves). It was nothing to do with a fear of deficits. When you are in a flexible exchange rate world, the parity makes the adjustment while fiscal policy can concentrate on the domestic economy.

Reagan in the US was not really a neo-liberal in the same (macro) sense of the word as Thatcher.

Inflation is certainly an issue that has to be confronted. That is why I advocate strong fiscal policy but with a nominal anchor provided by the Job Guarantee fixed wage. You get full employment without competing with the private market for resources that they desire. By definition, there is no market bid for the unemployed so there can be no inflation pressures coming from introducing a JG.

It is also clear that if an economy has x much real output you can divvy that up through the distribution system in a number of ways. In the full employment era we shared it more equitably and ensured workers were employed. In the neo-liberal era we cut the unemployed out of the equation and then ensured the profit share shifted significantly at the expense of the wage share. These are political choices.

I personally think the social debate has to be focused on collective will (as in the Scandinavian countries) where you feel personal benefit because others are getting material benefits. Sure enough an unequal distribution would give me more and you less (say). But a properly constructed public discourse would ensure I felt better having less and you more. That is the collective will sentiment that prevailed during the full employment era and there is nothing out there that has changed which negates it as a viable organising principle.

I also resent the arguments that arise the creating full employment via expansionary fiscal policy may cause the exchange rate to be lower (somewhat) which will make our imports more costly. This is tantamount to saying (although it is never framed in this way) that we are happier having people unemployed and socially excluded in order to allow the better off to pay a few percentage points less for their sports car or their winter skiing holiday. I don’t think that is a viable social ethic. I note these are not arguments you made but they are common out there.

best wishes

bill

Dear Lefty

The stagflation occurred because first there was a huge external supply shock (oil price rise) to oil dependent economies. There was no shortage of oil – just a well organised Cartel (OPEC) which could set the price at the level it desired. The reaction by Government was to contract demand while the reaction of organised labour and employers was to enter a slug-fest to determine which side of the workplace would sacrifice to make “real room” for the external cost shock. The latter generated a wage-price spiral while the former generated the first sharp rises in unemployment in years (and ultimately led to the abandonment of full employment).

Your interpretation is correct. The emerging neo-liberals saw this as a chance to implicate Governments and argue that the inflationary biases that full employment had slowly created were destructive and now out of control. This led to a new emphasis on inflation and using unemployment to discipline the wage-price struggle. Effectively, this shift in policy emphasis was refined into Monetarism then economic rationalism (the latter extending the macro arguments in micro demands for privatisation and welfare changes). Together this agenda is what I call neo-liberalism.

However, if the Governments of the day had have quickly intervened and mediated a distributional process to equitably distribute the cost shock without undermining aggregate demand then the period of disruption could have been short and we could have maintained full employment. They didn’t and we then entered this dark period of our history.

best wishes

bill

I thought that as long as the government ran surpluses, export earnings would be fairly irrelivent since private sector transactions net to zero.

Or does the Norwegian government control the oil industry.

cheers

Dear Lefty

I am writing a blog about this. A lot of people are interested in it. Coming later this afternoon.

best wishes

bill