Yesterday, the Bank of Japan increased its policy target rate for the first time in…

It’s simple math

Have you ever examined the Japanese yield curve? I check it on a daily basis. At present, it looks to have a normal shape (longer-maturities with slightly higher yields) than near-term assets. It is also quite low – like really low. The short-end around 0 and the long-end not much above it. It has been that way for a long time. If I assembled a group of economists – which we might call “distinguished experts” – and let them have the yield curve data and told them that inflation in this nation was low to negative and had been for two decades, and economic growth was mostly positive – and then asked them to write a story about the evolution of budget deficits and public debt ratios over the same period what do you think they would say? Alternatively, if we started with some other facts – like – increasing and relatively large budget deficits and the highest gross central government debt to GDP in the world – what would they say about inflation, growth and bond yields? The two sets of answers would be diametrically opposed to each other. The reason: because they don’t understand what drives the data. Their textbook macroeconomic models are totally wrong and have no explanatory capacity at all. It is really simple maths – a currency-issuing government can spend up to what is available for sale in that currency; can set yields and interest rates at whatever level is desires; does not need to issue debt anyway and so the notion of a financial collapse is misguided at best; and will cause inflation if it spends too much (defined as pushing the economy beyond its real capacity to produce). Simple really. Pity our “distinguished experts” didn’t see it.

There was an actual poll about – High Debt Countries – which asked the question:

Countries that let their debt loads get high risk losing control of their own fiscal sustainability, through an adverse feedback loop in which doubts by lenders lead to higher government bond rates, which in turn make debt problems more severe.

This is a cooked up poll conducted by the Initiative on Global Markets at University of Chicago as a publicity stunt to further their ideological interests.

The IGM tells us that their “panel was chosen to include distinguished experts with a keen interest in public policy from the major areas of economics … are all senior faculty at the most elite research universities in the United States”.

What exactly have they done to become distinguished experts. None of them as far as I can tell from an examination of their published work, for example, predicted the financial crisis. Some of them have been predicting the collapse of Japan for years. Regularly!

87 per cent agreed with 37 per cent strongly agreeing. When weighted by “confidence”, 48 per cent strongly agreed and overall 94 per cent agreed.

These polls are just a further public demonstration of how my profession continues to humiliate itself.

How many of these economists – these so-called distinguished experts – would be part of this self-aggrandising exercise and offer the same responses, if they were required to commit a year’s income if their predictions failed?

How many would be so arrogant to claim 10/10 confidence levels in their strongly agreed opinion if they had to put their money where their mouths were?

I know – you will say – that this bet would be problematic. For example, when would this bet have to end for us to judge success or failure of the prediction? Well, why not give Japan a decade to collapse. That should do it even though these types have been predicting the collapse for 2 decades already.

A decade from now should give the Japanese economy ample time to collapse under the burden of its public debt.

How many of them would put 10/10 on their confidence and say they strongly agree to the question for Japan with these rules? Answer: None. If they were pushed they would cite special circumstances or some other nonsense.

Professor Robert Hall from Stanford was one of those strongly agreeing with the proposition. I thought his comment justifying his strength of conviction in his response, summed it up:

Simple math…interesting that it has not happened to Japan, however.

Spare a moment Robert, and think why the “simple math” doesn’t add up!

Also, to all progressive-minded students, put all these institutions on your avoid list if you wish to enjoy an education in economics.

In this blog – almost one year ago to the day – A fiscal collapse is imminent – when? – sometime! – I wondered when things were going to collapse, given all the warnings from my professional colleagues.

If I took those warnings literally, then Japan would have collapsed under the burden of public debt in 1994, 1995, 1996, come to think of it again in 1997, 1998 and every year since.

Yes, they were just warming us up for the main event! Something or another happened to forestall the collapse. Just wait until it really happens. And all the rest of the vacuous qualifications that come from these sorts of opinions. I suppose just like Dr Alesina from Harvard I should attach a confidence rating of 10/10 that it is about to happen, given that he is a “distinguished expert”.

Well I am 10/10 confident that it will never happen, which probably makes me a nobody. I have been that confident for 20 years though. Nothing tells me otherwise.

Why am I so sure? Answer: Japan issues its own currency. It doesn’t have to borrow to spend. It can always meet its yen-liabilities. The bond markets are supplicants – hoping like hell that the government keeps issuing debt – the more the better – they are hooked on the corporate welfare!

On Monday (April 8, 2013), the Washington Post article – Why do people hate deficits? – was interesting although the journalist still couldn’t resist worrying about the US public debt levels. But, generally, it was a good contribution.

It considered the widely-held claims which lead people to hate deficits.

One of those claims – “Countries with debt over 90 percent of GDP enter a danger zone” – directly bears on the poll question.

Of-course, the 90 per cent threshold entered the debate “courtesy of Harvard economists Ken Rogoff and Carmen Reinhart” – the relevant paper being – Growth in a Time of Debt.

That paper talks about “debt intolerance limits” arising from “sharply rising interest rates” – and then “painful fiscal adjustments” and “outright default”.

It also talks about the “obvious connection” between inflation and high public debt ratios – which had me laughing because no-one has really shown that to be a robust relationship at all.

They note that:

… the manner in which debt builds up can be important. For example, war debts are arguably less problematic for future growth and inflation than large debts that are accumulated in peacetime. Postwar growth tends to be high as wartime allocation of manpower and resources funnels to the civilian economy. Moreover, high wartime government spending, typically the cause of the debt buildup, comes to a natural close as peace returns. In contrast, a peacetime debt explosion often reflects unstable political economy dynamics that can persist for very long periods.

Of-course, it would be inconvenient to their story to “attempt to determine the genesis of the debt buildups”. They want to simply engage in correlation analysis. If debt goes up and growth falls – bingo!

We fail first-year quantitative methods students who engage in this sort of analysis. Correlation does not equal causation!

Their work has been widely discredited by other economists for conveniently manipulating the way they conducted the analysis to suit their conclusions, for picking “the 90% figure almost arbitrarily” and most of all, in the context of my previous comments, for not admitting that “it’s much more likely that causality runs in the other direction” (quote from paper).

That means that it is more likely that countries with rising public debt to GDP ratios are those which are facing recession. The denominator (GDP) falls while the numerator (outstanding debt) rises, given the cyclical response of the budget balance (independent of any discretionary fiscal stimulus that such a nation might enjoy).

The Washington Post says:

Slow growth means lower tax revenue, greater social service payouts, and a whole lot of other factors that contribute to increased deficits and debt. It’s possible to tell a story where high debt hurts growth, but it’s much less intuitive and only holds when interest rates are high and choking off private investment.

Madam Reinhart dismissed this view and as “wishful thinking” telling the Washington Post that:

“We’re quite aware that you have causality going in both directions,” she says. “But please point out to me what episodes from 1800 to the present have we had advanced economies who carried high levels of debt growing as rapidly or more rapidly than the norm.” Belgium after World War I, she says, fits the bill, but that’s basically it. “It’s not about some exotic magic threshold where you cross the Rubicon,” she says. “But high debt levels are like a weak immune system.”

Given they are quite aware of this issue why didn’t they qualify their analysis in the paper? Why didn’t they seek to conduct causality tests, which are standard practice in this sort of exercise?

These tests are themselves open to question but they do provide extra information. If the tests were strongly supportive of their hypothesis and rejected the nulls of bivariate causality or the causality running as above – slow growth causes higher debt – then they would have had more credibility in their claims.

The journal they published this work in – the American Economic Review – is ranked among the top of the economics journals. These rankings have played a central role in the UK and Australian government systems of ranking economics departments or groups, with consequences for departmental funding etc. And they are crucial in determining who gets research money, promotion and jobs.

The fact that such a tawdry bit of work gets published in this journal tells me that the AER has no status in the context of “knowledge dissemination”. It is just another medium via which the ideological message of a degenerative paradigm (in the Lakatosian sense) uses to maintain its hegemony.

The Washington Post article also notes that:

So even Reinhart doesn’t think that 90 percent is a hard-and-fast cutoff. She simply believes that larger debt loads cause more and more of a problem for growth. That’s a contested issue, but even the economists being cited as supporting a point-of-no-return figure of 90 percent don’t believe that.

This is an important point.

The messages of doom are always couched in general terms – undated, surrounded by error bands, vague. The headlines do the damage – so people wake up to read – “Japan to Collapse, 94 per cent of Distinguished Economic Experts say so” – but they never appreciate how dishonest these claims are.

What debt ratio will finally bring Japan down?

When?

What will happen?

Only vague answers are offered at that level of interrogation.

Here is the Japanese 10-year Government Benchmark bond yield from August 1994 to March 2013 (Source). That is simple enough math for anyone to comprehend. Starts at

The 10-year bond rate started out (in this graph) in August 1994 at 4.6115 (average of observations for the month) and in March 2013 is standing at 0.6101.

This is not the US dollar we are talking about so it has nothing to do with reserve currency status. As an aside, the arguments that claim the US dollar gives the US government “super-MMT” capacities that other nations do not have are all spurious. I will consider that question another day.

The Australian government has all the power it needs to advance public purpose in Australia. It is called the Australian dollar and only one government issues that.

From 4.6115 to 0.6101 is simple math. We also know the budget deficit has risen. That is simple math.

We also know that inflation in Japan has been low to negative over the same period. That is simple math.

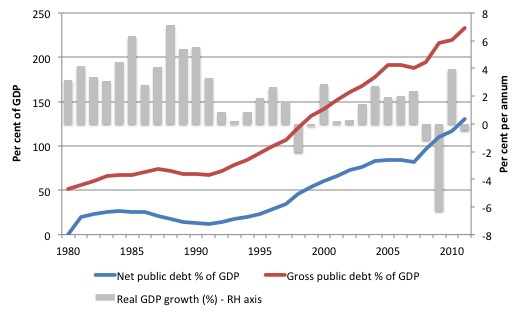

The next graph introduces the national debt statistics. It shows the evolution of gross debt and net debt as a percentage of GDP (left axis) since 1980 and on the right-axis (grey bars) the annual real GDP growth rate is plotted to provide cyclical information.

As an aside, Warren and I had a little laugh yesterday about how we present this data. It is obvious that the Gross Debt is much larger than the net debt. But we always like to emphasise the higher figure because it brings the rabid reactions out more quickly in question time at our presentations. It is fun to tease the worry-warts!

The IMF tells us what the difference between the two debt series is:

Net debt is calculated as gross debt minus financial assets corresponding to debt instruments. These financial assets are: monetary gold and SDRs, currency and deposits, debt securities, loans, insurance, pension, and standardized guarantee schemes, and other accounts receivable.

Gross debt consists of all liabilities that require payment or payments of interest and/or principal by the debtor to the creditor at a date or dates in the future. This includes debt liabilities in the form of SDRs, currency and deposits, debt securities, loans, insurance, pensions and standardized guarantee schemes, and other accounts payable.

The distinction is interesting for accounting purposes but, the currency-issuing Japanese government can always repay its gross debt irrespective of the other financial assets the central bank or finance department (treasury) might hold.

If we were back in early 2000s, we would be reading economists talking about exploding debt. A few years later as growth picked up again, the debt apparently stopped “exploding”

The behaviour of the public debt ratios is clearly cyclical and certainly not exponential. Just the use of terminology such as “exploding” is tainted and reveals an ideological bias in the commentary. The mathematical properties of the time series are fairly clear – there is no “exploding tendency”.

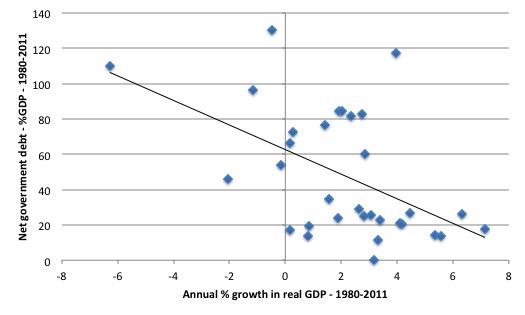

The next graph plots the annual real GDP growth rate on the horizontal axis against the net national debt as a per cent of GDP on the vertical axis. The black line is the simple linear regression trend line, which suggests that when growth is strong the national net debt ratio declines and vice versa. Yes, it could also say that when debt rises growth slows.

But if you examine when the conjunction of events it is rare that debt rises during a period of strong growth. The causality is almost definitely that slow growth leads to debt rising and when growth resumes, the debt ratio falls.

That is exactly what we would expect and why it is imperative to concentrate on growth rather than directly trying to reduce the financial ratios. We know from bitter experience that when the target of the policy becomes the financial ratios, real economic growth typically suffers and the financial ratios move in the opposite direction to the aim.

The slowdown in the late 1990s in Japan, was induced by an attempt to impose austerity on the economy because idiot economists pressured the government into believing there was an imminent collapse. The damage that fiscal contraction caused took some years to resolve (once the budget deficit was allowed to rise again).

I also found this Washington Post article (March 30, 2009) – Japan Debates Digging Itself Out – in my database today, which is tangentially relevant.

It is about the claims that deficits are terminal and have to be unwound through austerity.

We read that “three public works projects gummed up traffic one day last week” in Tokyo. The projects were part of the government’s fiscal response to the rapid slowdown in their economy in 2008.

The article intoned all the usual warnings:

The dilemma for Japan is that it has already been there and done that — in spades and not so long ago.

In the 1990s, during the “Lost Decade” that followed the bursting of a real estate bubble, Japan’s government spent more than $2 trillion on public works. In so doing, it dug itself the deepest public-debt hole in the history of the developed world, totaling more than 175 percent of the country’s gross domestic product.

All the spending has made Japan’s infrastructure the envy of the world. It has a public transportation system that is unrivaled for convenience and ubiquity. Its fiber-optic broadband infrastructure enables the world’s fastest Internet connections, delivering more data at a lower cost than anywhere else.

And not to mention that it largely avoided a major recession after its property market boom burst in the early 1990s and it kept its unemployment largely from rising during that period.

Win-Win to me.

But it was the comment of Richard Koo that I wanted to remind you of:

You can bash public works all you want, but in this type of recession, where companies and individuals have stopped spending, government expenditures become absolutely essential … We need speed more than anything in responding to this crisis … Our unemployment rate never went above 5.5 percent … Public works was an extremely effective fiscal stimulus, even though a few projects were really stupid.

Conclusion

Another day of humiliation for the mainstream economics profession!

Tomorrow, the ABS publishes the March Labour Force data and at some point that will occupy my mind.

Ken Loach – The Spirit of ’49

Today, I ordered Ken Loach’s latest film – The Spirit of ’45 – which traces the reasons why the Welfare State emerged in Post World War II Britain. I am looking forward to watching it. We might have to have a “unity in socialism” viewing!

You can also see an interesting interview with Ken Loach – HERE.

One of my favourite documentary-film makers.

Here is a trailer for the film.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

I accept your MMT mantra that currency issuing countries don’t/can’t have large deficit problems. But then I read yesterday that Indonesia has just achieved excellent prices and big over-subscriptions for its U$3 billion bonds issue http://www.thejakartaglobe.com/business/indonesias-3b-bond-sale-helps-rupiah-gain-on-dollar/584710 and the question arises: why would they do that? Why not sell bonds in their own currency? Doesn’t this hang their future on the U$ exchange rate?

@cambowambo,

Possibly the same reason why anybody wants to borrow a currency they don’t issue: they want to buy things (or payback previous debt) priced in USD and don’t have enough of it at the moment.

It exposes them to the actual risk of default, if in the future they are unable to obtain enough USD (by exporting goods and services in exchange of USD) to match their repayments.

I think MMT would say that, if you are a currency issuer, borrowing in another currency sort of allows you to spend now (in the foreign currency) the profits of your future exports. The risk being that you are unable to export enough in the future and have to default on your foreign denominated debt, exposing you to Uncle Sam’s, the IMF’s and/or World Bank’s wrist slapping, loss of sovereignty and/or imposed austerity measures, diplomatic sanctions, and other fun things up their sleeve.

And remembering that exports are a real cost and imports are a real benefits, it means you’d enjoy real goods and services coming from abroad now, in exchange of giving back more (interests are a bitch!) of your national goods and services to them in the future.

I’m only am enthusiast and regular reader, not an economist, so take this for what it’s worth (which isn’t much!).

Sov Japan and non sov Europe share one physical economic characteristic .

They are both extreme entrepot economies.

“a currency-issuing government can spend up to what is available for sale in that currency; can set yields and interest rates at whatever level is desires; does not need to issue debt anyway and so the notion of a financial collapse is misguided at best”

The key words “what is available for sale in its currency”

Australia and the US can access their own hinterland to a greater extent but not the above countries.

Japan is suffering from a irrational Nuclear shutdown which has thrown the entire global LNG market into chaos.

There is currently a trans ocean global catfight between the UK & Japan over Qatar Nat gas.

(the UK was its biggest customer until the Jap explosion)

If Japan inflates the UK will get to eat all the LNG pies again.

How will that work out for Japan ?

Not good me thinks.

I quess Japan has some sort of “funded” pension scheme. That would explain growing divergence between net debt and gross debt. They have to keep deficit spending just to fund some giant, monstreus pension fund.

It would be nice to get some analysis what is on the asset side of the government’s balance sheet.

Looking at the data for Japan, the net increase in government debt, exceeded the growth in GDP growth in every year over that period. Proponents of deficit spending always say that the multiplier of government spending is above 1x, however in Japan’s case the evidence certainly doesn’t demonstrate this.

Also, isn’t Japan a special case given its consistent trade deficit, resulting in it constantly having an excess of foreign currency and not having to worry about attracting foreigner to hold its bonds in order to finance imports.