I have received several E-mails over the last few weeks that suggest that the economics…

Australian PBO – another myth-making neo-liberal institution

The economics journalists were out in force again today in Australia after being fed their latest copy from the neo-liberal propaganda machine. In this case, the propaganda was in the form of the first report published yesterday (May 22, 2013) from the newly established Parliamentary Budget Office – Estimates of the structural budget balance of the Australian Government 2001-02 to 2016-17. The Report estimates that huge unsustainable budget deficits and has led to a flurry of media activity all just repeating what the PBO told them was the message. I wonder if any of the journalists have actually read the report in detail particularly the Appendix where the technicalities are exposed. Technicalities is too strong a word because it suggests there is something robust going on. Nothing could be further from the truth. This is another shoddy attempt to bias the public perception towards thinking the current (pitifully small relative to the scale of the problem) budget deficit is problematic.

The Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO) is one of those neo-liberal constructs where the government establishes a so-called non-partisan, independent budget watchdog to advise it on fiscal policy. The body is unelected and unaccountable to the people.

Yet, everytime it makes a noise the lazy economics media jumps to attention, gets their copy for the day from the PBO press release and the elected government is immediately under pressure because “the deficit is too big”; “we have a structural blow-out” or all the usual mis-guided headlines that appear the next day.

These organisations are designed to reduce the discretion of governments to use fiscal policy in the interests of the well-being of the people. They bias fiscal outcomes to being too restrictive and maintain much higher levels of labour underutilisation that is necessary.

They perpetuate the worst lies that my profession push into the public debate – all the usual deficit and budget myths. They are essentially anti-democratic and anti-prosperity.

The PBO claim that the Report:

… is the first in a series of reports that the PBO proposes to issue to help explain how underlying budgetary trends and discretionary fiscal policy decisions impact on the government’s fiscal position.

They will excuse me if I roll off my chair laughing. Explanation is about provided connected knowledge. This Report is a fudge around a miss-mash of orthodox theory which provides very little credible information to inform fiscal policy decisions.

It supports the mainstream view that structural budget deficits are undesirable.

The purpose of the Report is to provide estimates of the structural budget balance (SBB) which they claim is:

… a partial measure of the sustainability of the budget

Whatever that means. What they mean by this is meaningless in the case of a currency-issuer such as the Australian government. They have some insolvency model underpinning their view that budgets should generally be in surplus.

There is never a solvency issue with respect to the Australian government budget. The only thing the federal government should worry about it whether they are providing enough spending support to the economy to ensure there is no output gap and everyone who wants a job can find one.

That is the sustainable budget position.

Please read my blog – The full employment budget deficit condition – for more discussion on this point.

Also please read the following introductory suite of blogs – Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 1 – Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 2 – Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 3 – to learn how Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) constructs the concept of fiscal sustainability.

After the press release yesterday by the PBO, there was a flurry of news reports. For example, in this morning’s Melbourne Age there was an article – Telstra cuts jobs amid bleak outlook.

It said:

… the new Parliamentary Budget Office blamed both sides for Australia’s slide into a structural budget deficit – a deficit Treasury warns is now likely to remain for another six years … In its debut research paper, the budget office estimates Australia will still be in significant budget deficit in 2016-17, even though the budget papers forecast a $6.6 billion surplus by then.

That is, it accepted without question the PBO estimates released yesterday.

Weren’t the economic journalists the slightest bit curious to see whether the estimates could be trusted as reliable indicators of the actual position?

Further, they reinforced the current fears that this “slide into a structural budget deficit” is something that we should be worried about.

Our National Broadcaster, the ABC ran a story late yesterday after the PBO release – oe Hockey defends Howard government tax cuts after reports say they contributed to structural deficit.

The author once again reinforced the myths and chose to quote the Access economics director (who is used all the time by the ABC) who said the following:

The usefulness of the figures out of both the Parliamentary Budget Office and the Treasury is it’s underscoring the fact that the budget is in more trouble than it looks … We overdid it. We’ve overdone it for a decade.

Australia did over do for a decade or more – they ran excessive surpluses. That is why there were still 9.9 per cent of people unemployed or underemployed at the peak of the last cycle.

The Access commentator claimed that the release of the PBO report was “great day for Australia” and:

The Parliamentary Budget Office has that greater degree of independence and Australians need to hear the message that the politicians on both sides aren’t telling us.

And … not one journalist during yesterday or overnight has questioned these PBO estimates. They are now part of the bank of “facts” that deficit frenzy in the press draws upon.

Our fourth estate is largely a failure. They are mostly mouthpieces, waiting for the next press release, which they faithfully reproduce. I asked on journalist recently why their story was so unbalanced. I was told that there wasn’t enough time between the filing deadline and the release of the embargoed report.

The question then is why go along with the press manipulation by the organisation releasing the report. If they manage the schedule so that they cannot be attacked by those critical then the press should just tell them to take a long walk of a very short pier.

But no, the article was uncritical and created an aura of respectability to a piece of analysis that was poor at best.

In compiling their estimates of the SBB they say:

The estimates have been prepared using internationally accepted methodologies.

Which, of-course, doesn’t make them right. The whole clutch of neo-liberal organisations use methods which deny reality – in particular they assume economies are much closer to full capacity than any reasonable estimate of the output gap would conclude.

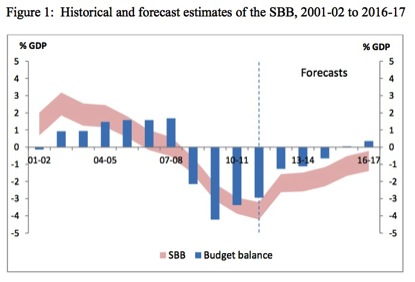

They produce the following graph (their Figure 1).

The supporting text is fall of words like “a sharp improvement” if the SBB fell and “recovering” when it fell further. They say that “Based on the latest budget estimates further improvement is expected from 2013-14”. So you immediately grasp the ideological position the PBO adopts – a rising deficit is a deterioration and vice-versa.

On what grounds? Simply because they think surpluses are good and deficits are bad.

Note the estimated “further improvement” coincides with estimates in the 2013-14 Budget of fall real GDP growth (further off trend) and rising unemployment rates.

In this 2010 interview with the ABC current affairs program PM (May 13, 2010) – Modern Labor’s full employment – half a million out of work – the Treasurer was asked to define full employment.

He said:

Best of all, the unemployment rate is expected to fall further from 5.3 per cent today, to four-and-three-quarter per cent by mid 2012; around a level consistent with full employment

We can dispute the full employment benchmark defined here but he was wrong. Unemployment has risen since and is forecast in the 2013-14 Budget to rise further to be 5.75 per cent in 2013-14 fiscal year. That is an optimistic forecast. I suspect it will go higher.

But the point is that the PBO is now pumping out so-called independent research analysis which defines a “further improvement” in the fiscal position of the government as being associated with a rise in the unemployment rate, which even on the Treasurer’s own assessment is 1 per cent higher than his definition of full employment. That is 125 thousand people on current labour force size.

But that doesn’t take into account the lower participation rate that will result (pushing up hidden unemployment) and the rising underemployment.

Why didn’t any of the economics journalists point that out today?

But have a look at the graph. The broad SBB line reflects their margin of error and define what they claim is a “a plausible band”. Okay so lets look at 2011-12. Based on this reasoning, there was zero cyclical component to the budget deficit – that is, the SBB was larger than the actual budget balance.

Remember that the SBB is “the underlying position of the budget after adjusting the actual budget balance for the impacts of major cyclical and temporary factors”.

In other words, once you take out the cyclical and “temporary factors”, the PBO is claiming the Australian economy was at over-full employment – beyond its capacity.

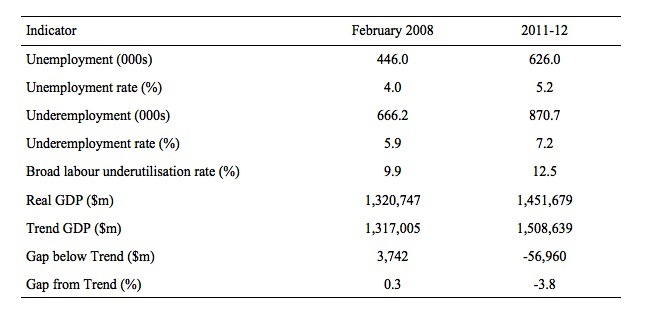

The following Table provides a comparison between the peak at the end of the last cycle and the position over 2011-12 – the PBO’s so-called over-full capacity year where there were no cyclical factors impacting on the budget outcome.

For the labour force aggregates I have used February 2008, which was the low-point unemployment rate; whereas for the national accounts aggregates I have used the fiscal year. There is not much hinging on that choice.

I have run econometric and other types of statistical models all my career. I have supervised several successful PhD students who have also estimated things. The rule of thumb is when you estimate something you check the forecasts/projections against reality. If the estimates seem far-fetched when confronted with what you actually know then you can be sure something is wrong with the methodology being used to generate the estimates.

Make up your own mind but if the left-hand column was the best we could do out of the last cycle then what assessment are you going to make about 2011-12 outcomes.

Any reasonable person would conclude that things have got worse. That is couldn’t possibly make any sense to construct a situation where if the economy had have maintained its trend growth (between 2000-2008) of 3.05 per cent after 2007-08, then it would be some $A59,960 million or 3.8 per cent larger than it was in 2011-12.

Or that a rise in total labour underutilisation from 9.9 per cent to 12.5 per cent is a deterioration and represents extra productive capacity not being utilised.

The participation rate in 2011-12 was also 0.4 points below the peak of November 2010, which means that an extra 102 thousand workers who wanted to work were officially classified as being discouraged when compared to the 2010 peak.

The PBO know that the average person won’t be able to debate these technical matters and so they just lie and rely on the clutch of economics journalists then to spread the lie as widely as they have readers and listeners.

Why didn’t any of the economics journalists question that aspect of the PBO modelling today? They were too busy trying to make some political points out of the PBO estimates rather than working out whether the estimates made any sense in the first place.

You can see that in the 2012-13 fiscal year the gap between the actual budget balance and the PBO estimate of the SBB widens. In other words, even though unemployment and broader labour underutilisation have increased and real GDP fallen further below trend output, the PBO thinks the economy has gone further into an over-full capacity state.

If a first-year student produced this sort of analysis I would fail them immediately. The PBO work is very shoddy.

I won’t get into the subsequent analysis presented by the PBO – just a waste of time really. But it is educative to examine the information presented in the Appendix because it is there you can work out how they came up with their SBB estimates.

The steps in the calculations are straightforward:

1. “the cyclically-adjusted budget balance (CAB) is calculated … [by removing] … the cyclical component of the actual budget balance … To do this an estimate is made of the extent to which the actual output of the economy is either above or below the economy’s potential output, that is output produced when the economy is operating at full capacity, consistent with stable inflation.”

2. “Having derived an estimate of the output gap it is then necessary to determine the impact of the output gap on the budget balance by estimating the sensitivity of tax revenue and government expenditure to this gap”.

How did they estimate potential GDP?

To estimate potential production they use a – Cobb-Douglas production function – which is one of the arbitrary mathematical constructs that the mainstream pull out because under the assumption of perfect competition it presents “desirable” properties – that is, results that match their theory.

Thus, it embodies the “law of diminishing returns”, fixed factor shares (under perfect competition) and typically, constant returns to scale.

So it imposes a particular world view on empirical analysis which constrains (biases) the analysis from the outset.

For those interested in history, the Cobb-Douglas production function first was really launched in an article published by Paul Douglas in 1948 (it was his presidential address to the 1947 American Economic Association). Much earlier (1928) he had published an article with Charles Cobb which defined the function.

Douglas, by the way, was one of several authors of the 1939 paper – A_Program_for_Monetary_Reform – (aka The Chicago Plan) which has enjoyed somewhat of a revival in the literature in the last year. It is a flawed plan though which I might write about sometime in the future.

[References: Cobb, C.W. and Douglas, P.H. (1928) ‘A Theory of Production’, American Economic Review, 18 (Supplement), 139-165; and Douglas, P.H. (1948) ‘Are There Laws of Production?’, American Economic Review, 38(1), 1-41]

These constructs were theoretically demolished (by the Cambridge Critique) and then proponents claimed that it didn’t matter that we could not derive the function in a way consistent with the underlying theory (that is, it did not have solid theoretical foundations) as long as the empirical results were consistent with that neo-classical theory.

It was an extraordinary example of the way the mainstream enters denial when their approach is shown without doubt to be flawed. This was not just a matter of opinion. It was a case of their theory being internally inconsistent even on their own grounds.

There reaction – never mind … students, turn to page 20, where we see the aggregate Cobb-Douglas production function … let’s proceed.

Somewhat later, New School economist Anwar Shaikh established that the production function had no empirical relevance (he called it a “humbug function”).

[Reference: Shaikh, A. (1974) ‘Laws of Production and Laws of Algebra: The Humbug Production Function’, The Review of Economics and Statistics, 56(1), 115-120]

That devastating critique washed of the mainstream’s back like the water from a duck’s back. Denial again. Just ignore it and it will go away.

The PBO also seem to have constrained the function’s coefficient to 0.6 (hours worked – labour input) and 0.4 (capital input). This implies a wage share in factor shares of 60 per cent. It is currently around 52 per cent, which means they are over-weighting the employment input. The first area of bias.

The inputs to the Cobb-Douglas production function are trends in employment by hours, capital stock and total factor productivity.

How did they compute the trend in hours worked?

They used the formula:

Trend hours worked = (working age population x trend participation rate x (1 – trend unemployment rate) x trend average weekly hours worked) x 52

Note: at the outset the stated object of the exercise was to estimate potential output – which by any meaning is the maximum the economy can produce if all its productive resources are being deployed to their own potential.

But you will see that without explanation, the PBO slips trend in for potential. The two concepts are different. Trend is the underlying (non-cyclical) pattern of the time series.

But imagine an economy in chronic recession, the trend measure of, say unemployment would bear no relationship to a reasonable definition of full employment.

It is true that a persistently weak trend will eventually cause damage to the potential path. But it is unreasonable to replace trend and call it potential. At present the economy is growing somewhere around 2.5 per cent annum well below the 3.05 trend that it achieved up to the crisis.

Unless there has been major destruction of productive capital and fundamental shifts in worker preferences to retirement then 3.05 is about what we should expect the trend growth to be at present. So 2.5 is below trend which means even by that benchmark there is excess capacity. But then that trend was still associated with persistently high labour underutilisation which makes the excess capacity at present even worse.

Anyway, the PBO then proceeded to compute trends for each of these components (other than working age population) using a filtering technique – Hodrick-Prescott filter. All this does is smooths out a time series. It tells you nothing about the relationship between that time series and, for example, its potential maximum or minimum value.

So if an unemployment rate has been very high for say a decade, the HP filter will produce a smooth series of that very high unemployment rate. To infer that was a full capacity component is ridiculous in the extreme.

Also the HP technique, while useful to see smoothed trends, has serious flaws. As it is a purely backward looking measure it is known to cause misleading estimates of future values because, unlike a moving average filter, the HP estimate of the past state of the series is sensitive to each future value.

This relates to the so-called end-point problem that all stochastic filters encounter. I will spare you the technicalities but essentially you can only filter up to a certain point and then the filter can change significantly as you add observations irrespective of whether the added observations are in this context cyclical or trend.

The HP filter is particularly affected by this problem (unlike other time-series filters).

The way to overcome the “end-point” problem is to extend the time series and then apply the filter over the extended horizon. This can clearly introduce bias if the “made up” observations do not turn out to be accurate when time catches up with them.

The HP filter approach cannot deal with these sorts of errors and so are prone to producing biased trend estimates in extended samples.

A way of minimising this problem is to extend the time-series based on a model which is close to the true data generating process (that is, having a reliable forecasting model).

I could go further but then I would have to introduce very technical matters that do not belong on my blog (given the readership).

The question is how did the PBO choose to extend the time series to allow it to use HP filters to generate future trends?

Not much imagination was used I am afraid.

We read:

The unemployment rate and the participation rate utilise the 2013-14 Budget medium-term projections to address the end-point problem of the filter.

It is almost laughable – are these characters kidding us with this type of stuff? The problem is as a comedy it is great but in reality the consequences of this folly are tragically large – hundreds of thousands of jobs large.

The result is that trend unemployment hovers around 5.6 per cent out to 2016-17, participation falls about 0.75 per cent (note it is already well below its recent peak) and average hours worked is totally flat – that is, no change expected in the period out to 2016-17.

The result is of-course predictable. The output gap they produce is miniscule for the current period and beyond, which means that the measure of the structural deficit they come up with is much larger (in terms of its proportion of the actual budget outcome) because they are grossly underestimating the cyclical component in the actual budget outcome.

This is classic IMF/OECD tactics and then leads them to advocate fiscal austerity even though the degree of fiscal support for aggregate demand is much lower than they claim.

Then fiscal policy becomes pro-cyclical and the austerity bias sets in.

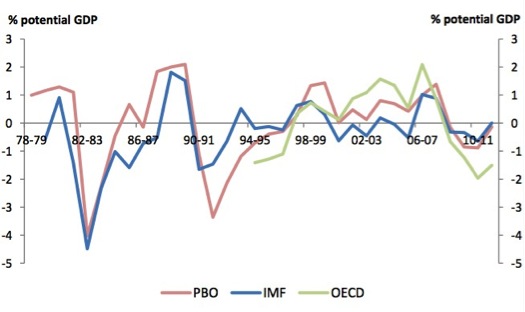

The PBO produced this graph of the output gap – comparing the OECD, IMF and their own measures.

I don’t have their data and I haven’t time to reverse-engineer their estimates from the graph. But you will recall I went through this exercise a few weeks ago.

Please read my blog – Australia output gap – not close to full capacity – for more discussion on this point.

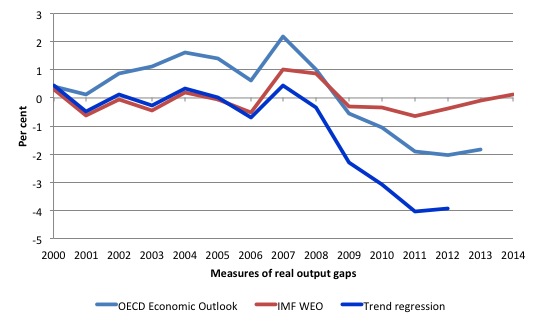

My method was less open to bias. The RBA and Treasury have from time-to-time indicated they considered the trend growth rate to be between 3.1 and 3.5 per cent.

With that in mind, I did a regression analysis of trend. The method was standard. Real GDP was decomposed into its trend and cyclical components and for the period 2000Q1 to 2008Q1.

The estimated model was then forecast out-of-sample (dynamic) for the period 2008Q2 to the most recent observation 2012Q4. The forecasted trend series can be interpreted as telling us what would have happened to the evolution of real GDP if the GFC had not have occurred and the Government had not pursued its surplus obsession.

This model is entirely plausible and fits well with other data indicators that are available which I will consider in further background papers in the coming days.

The trend rate of real GDP growth for the period was 3.05 per cent. So it is entirely within the ballpark that the RBA and Treasury use (in fact just below their oft-quoted estimates). So there is no bias entering there.

I then computed the gap between trend output and actual output for the forecast period. Note that the gap between real GDP and trend GDP is not strictly an output gap because that would require the additional assumption that trend growth always defines the potential growth of the economy. An economy may be held in a state of austerity for years (as we are seeing in Europe at present) and its trend will be much lower than its potential – given that tens of thousands to millions of people might be persistently unemployed or underemployed.

So we should more accurately call the gap between real GDP and trend GDP to be an incremental output gap because it does not presume that the trend output upon which the forecast was based coincided with potential output or full employment.

In the context of my measure, the incremental output gap depicts the increase in whatever gap existed at the time the model forecast began (March-quarter 2013).

The following graph compares the IMF and OECD estimates with my “incremental output gap” measure. You can then more easily compare my measure with the PBO measure using the IMF/OECD relativities as guide posts.

So while the PBO is claiming there is an output gap of less than 1 per cent at present and close to zero, the OECD estimates it to be around 2 per cent in 2012 and my estimate is closer to 4 per cent.

My method is so transparent and so insensitive to technical manipulation that what the PBO and all the journalists who choose to advertise their work have to be able to demonstrate is why they assume the output gaps are close to zero when it is more likely closer to at least $60 billion.

What they have to be able to show is that the trend rate of growth of 3.05 is a massive over-estimate of the what the economy is capable of achieving in the next few years.

What has changed which might justify such a bizarre conclusion? Nothing – labour hasn’t migrated (like in Ireland, Latvia, Spain etc for example).

Why don’t all the economics journalists demand that sort of answer from the PBO? It is a simple question – Do you think trend real GDP growth is around 3.1 per cent? Yes or No?

If Yes, then there is no way the PBO estimates (nor the IMF estimates) are remotely true.

If that is the case, then their estimates of the SBB are useless and the whole department should be closed down. It is an ideological beast with no place in a democracy.

Conclusion

Another day of angst dealing with this stuff.

At some point in future history we are going to be exposed for what we are – stupid, dim-witted idiots – who soak up bulls***$ every day from the elites and their sycophants (including the fourth estate), whose only objective is to screw more of the real income out of our share.

I need some fresh air.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Well, apparently we are made of 70% water Bill (H20); the rest is mainly Calcium, Carbon, Nitrogen, Phosphorous with a few trace elements in the mix. What sort of consciousness were you expecting??

(Hope that made you laugh)!!!

Bill, do you have a view about the Tim Worstal post: “Modern Monetary Theory Means We Shouldn’t Have A Progressive Tax System” in Forbes 4/20/13? It gleefully points out what has always seemed to me the very big flaw in MMT:

“The people who support MMT tend to be over at the more progressive end of the lefty spectrum. Not entirely but it’s a definite tendency. And these are entirely the people who would be horrified at the thought of abandoning progressive taxation in favour of a regressive system. But as far as I can see MMT destroys the argument in favour of progressive taxation and, given that we only tax now in order to curb inflation, insists that we must move to an entirely consumption based tax system. One that will be, by necessity, a regressive tax system. I wonder how they justify this to themselves: or even, to be honest again, whether they’ve even noted this contradiction?”

@stone,

my two cents from an average MMT blog reader’s point of view: it seems that the author has interpreted “we only tax to curb inflation” into his own views. From what I read, MMT is consistent with regressive, progressive, flat or whatever taxation system is in place, as long as there is one.

My brief critique to the author’s point would go like this: First we don’t “only tax to curb inflation”. There needs to be some level of aggregate taxation to create demand for the national currency. This aggregate level of taxation (obviously in conjunction with the spending side of the government budget) needs to be adjusted to match the private sector’s spending/saving decisions in aggregate. After that who and/or what you tax/spend on can then be debated and fine tuned in accordance to your political views, the type of activity you want to (dis)incentivise, the income and wealth distribution you are aiming towards, and so on…

@stone

MMT says taxes are imposed to temper inflation. The single item experiencing the greatest inflation these days (in the US, at least) is the price of buying elections. It’s quite obvious that these elections are primarily being bought by the ultra-wealthy, and so if we care about keeping the price of buying elections low, a heavily-progressive tax system would certainly be a good idea.

See? Worstal is wrong. MMT actually does support progressive taxation.

If it weren’t for reading this blog I would be in the same boat with those stupid, dim-witted idiots, so thanks for the life preserver. And, thanks for not making it too technical.

@Tristan and Benedict

To me the most important role of taxation is to prevent aggregation of political and financial power. You guys now seem to be agreeing but I think Tim Worstal is correct in saying that many MMTers only mention this if and when pushed on the subject. Generally a pretense is made that net saving desires can be accommodated willy nilly without the consequences of that derailing the economy by creating an immensely powerful political force behind maximizing the value of government debt securities which entails economic depression.

MMTers should be more careful when claiming that taxes only exist to control inflation. The latter statement is too much of a jolt for those we are trying to convert.

It would be better (and I think more accurate) to say something like this. “It’s perfectly valid to regard taxes as existing only to control inflation. But it’s equally valid to regard taxes as existing basically to fund public spending, while DIFFERENCES between tax and public spending are useful for controlling inflation and bring stimulus.”

@Ralph

Tim Worstal’s point (and mine) is that there are very different forms of taxation. It is utterly different to levy a sales tax (or cigaret duty or whatever) or to levy an asset tax. As Tim Worstal points out (as did Michal Kalecki in 1937) taxing wealth does not reduce aggregate demand. It won’t reduce CPI inflation. By contrast consumption taxes massively impact aggregate demand. The dollars taken in by taxation are not really the issue -its the TYPE of taxation that determines what aggregate demand will be. By freeing property from taxation and cranking up government deficits it is possible to transfer financial and political power over to the richest.

@stone,

Why do you bring government debt securities in here? If the budget is in deficit, there is no need to issue a matching amount of debt. Government debt serves a completely different purpose.

The subject of taxation is constantly mentioned in the academic works of most MMTers, I disagree with the claim that they avoid the subject.

Also the claim that “net savings can be accommodated willy nilly without the consequences of that derailing the economy” has never been made by the MMT literature I have had access to. Wherever you see a claim that spending/savings desires can be accommodated, you will always see in the same sentence or paragraph something along the line “as long as there are real resources available to do so”.

It seems to me that, often when people claim something is rarely mentioned or is ignored by MMT, a cursory check of the academic literature, or even this very website will prove them wrong. Bill voiced his exasperation of this type of claims (albeit on another subject) in this blog https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=22701

@Tristan Lanfrey “Wherever you see a claim that spending/savings desires can be accommodated, you will always see in the same sentence or paragraph something along the line “as long as there are real resources available to do so”.”

If the deficit is purely accommodating net saving desires then by definition there will be enough real resources available. IMO the whole point of running deficits is to allow wealth to be accumulated by the private sector that does NOT involve real resources. That wealth is simply a claim. It costs nothing real to create such a claim but the holders of those claims will do everything to maximize the value of the claims they hold. You say that I shouldn’t have brought in government debt securities- well even if the government doesn’t issue bonds and simply funds the deficit by creating debt free money -that debt free money is a financial claim that will have a value that will be guarded by political lobbying and that debt free money will convey political power to those that hold it.

Bank credit is a very serious threat to the monetary sovereign’s ability to deficit spend without price inflation. How long till the MMT crowd realizes this?

But if endogenous money is so important, it can be done without a government-backed credit cartel. Common stock is an ethical form of endogenous private money that does not require usury, a central bank, or deposit insurance.

@stone,

“well even if the government doesn’t issue bonds and simply funds the deficit by creating debt free money -that debt free money is a financial claim that will have a value that will be guarded by political lobbying and that debt free money will convey political power to those that hold it.”

I suppose that’s where a progressive tax system has to step in. So we’ve proved Worstal is wrong 🙂

A progressive tax system is also part of the automatic stabilisers. As incomes fall in a recession, tax liabilities fall even faster, helping to stabilise demand in the economy. I think MMT is all for automatic stabilisers.

MMT differentiates between what needs to be done when there is spare capacity and when there is none.

CharlesJ, I think it could be argued that a regressive tax system could be just as good if not better as an automatic stabilizer than a progressive tax. If you focussed tax on poor people and absolved from tax anyone with an annual income over a million dollars or assets over ten million dollars then when there was a recession and working class people lost their jobs, you would get a big drop in tax take.

IMO MMT seems to fail to face up to the reality that tax is needed to ensure dispersed political and financial power -its not just about inflation.

Dear stone (2013/05/24 at 5:18)

You are too clever to make statements such as:

If you undertake a textual analysis of the body of work now considered to be MMT you won’t find evidence to support your assertion. You will find discussion about the role of taxation as a macroeconomic instrument to condition the overall level of purchasing power (the inflation argument); the need for equity (that is, who has the private purchasing power – the progressive etc); the need to alter resource allocation by discriminating against certain activities (for example, tobacco, environmental issues etc) and the need to maintain a demand for the currency (intrinsic).

Okay. So stop trying to be simplistic.

Further, the article you mentioned was very poorly written. It fails at the first step because it fails to understand that the progression in the fiscal system can only be applied to the mix of spending and taxation. You cannot conclude what level of progression there is by considering, say, the structure of the income tax system. A nation could have a highly regressive fiscal system overall with a progressive income tax structure as much as a nation could have a highly progressive fiscal structure with mostly regressive taxes being components of that system.

best wishes

bill

Off topic but I feel Bill will like this.

James Meeks classic poetic look at the UKs energy disaster – especially post privatization.

A must read and the audio is great.

http://www.lrb.co.uk/v34/n17/james-meek/how-we-happened-to-sell-off-our-electricity

Bill, whilst you lost me in some technicalities in the latter half of the post, I do agree with the overall sentiment which is why I opposed the PBO since conception. I presume it uses all the same assumptions that the US CBO does.

Stone: Why not look at MMT classics from before most MMTers were born? That understand and deal with your concerns adequately:

Like Beardsley Ruml’s Taxation for Revenue is Obsolete. Or Dudley Dillard’s great book on Keynes, a lesser known favorite of mine, quite MMT friendly imho.

You are knocking down a straw man of your own making.

MMT is a scientific theory. You can do with it what you want. If you want to concentrate financial and political power by means of sound economic knowledge, you can. If that is not your purpose, you can do something else.

Just like meteorology is a scientific theory. If you are an Evil Space Alien Invader from a planet that is hotter and has a different atmosphere from Earth’s, you will use your Superior Alien Meteorological Science to convince the foolish Earthlings to change their planet to one more to your liking. And they won’t catch on to what’s happening until it is Too Late. Bwaahhaaaahaaaa!!!!

Doesn’t mean that there is a defect in Superior Alien Meteorological Science. It is just that the Evil Space Aliens are applying their correct scientific theory agains the foolish humans.

Generally a pretense is made that net saving desires can be accommodated willy nilly without the consequences of that derailing the economy by creating an immensely powerful political force behind maximizing the value of government debt securities which entails economic depression.

It seems to me that a core problem you still have is that this consequence, this conclusion you leap to is generally FALSE, but that you think it MUST be true, so much so that it goes without saying. To be simplistic:

Austerity, neoliberalism tends to be strongly associated with “the rich getting richer, the poor getting poorer” and BIGGER deficits and (public and private) debt. And asset bubbles.

Free spending, accomodating savings desires, full employment like the postwar era, the New Deal in the USA – tends to be associated with flatter, fairer income distributions and LOWER debt and deficits, lower inflation, no asset bubbles. Functional finance is sounder than sound finance, as Lerner understood well.

There is no “pretense” necessary – because the effect of good MMT deficit spending accomodating savings desires is usually the reverse of what you think. It doesn’t create an Evil Political Force – it fights it!

By freeing property from taxation and cranking up government deficits it is possible to transfer financial and political power over to the richest. To give you your due. Yes. This is in essence part of the criticism of Galbraith (and I believe Minsky too) against the trend started by the USA’s Kennedy-Johnson tax cuts (for the rich) stimulation. But keeping the tax system fixed, as above, you have no argument, theoretical or empirical, against good MMT/Keynesian public works, JG spending.

Bill and Someguy, I appreciate that it could cause you some exasperation that after three years of trying to get my head around MMT I still am stumbling on this -thanks for your patience.

To some extent MMT is supposed to be describing what is actually happening rather than what we hope for. I would be less uncomfortable with MMT if MMT came straight out with it -loud and proud- and said that modern money offers possibilities for good and also a great danger in that it allows continued deficit spending to incrementally and very indirectly transfer power to the richest and so we need to be especially aware of that danger when we have a MMT compatible monetary system.

Someguy, the neoliberal Reaganomics system was using a MMT compatible monetary system wasn’t it? If you say MMT is simply describing how modern money works then that Reaganomics and its current consequence is what we are dealing with.

Bill I get your point about the general fiscal mix having to be seen together in order to work out whether it is progressive – I’ve read that Scandinavia countries have (or had) a more progressive fiscal system than the USA despite an apparently LESS progressive style of taxation simply because Scandinavian government spending was massively more progressive (child care in Scandinavia, nuclear bombs in USA). In conjunction with big deficits (something that Scandinavia never sustained did they?) doesn’t progressive government spending and tax breaks for the richest create a perfect storm in terms of creating wealth polarization? The progressive spending keeps the economy afloat whilst the deficits pass on through to become amassed wealth for the very wealthiest. The next stage in the inevitable evolution of it all is that the wealthiest then demand austerity and they have the wealth and power to get what they demand.

Someguy you do seem to me to have a blind spot on this. In the UK the “new labour” government spent money on free education for under fives etc etc and the spending on that passed through to be collected as profits and amassed as concentrated wealth. The recipients of the spending spend again and each time a little gets harvested and stored as wealth- the spending can be progressive but the final resting point of the wealth is anything but.

I totally agree that neoliberalism and austerity lead to a mess. My point is that we need all the spending MMTers want, all the tax cuts (total end to them IMO) in payroll taxes, sales taxes etc that MMTers want BUT have an asset tax to prevent an expanding stock of government net financial assets. The fear I was expressing is that austerity is an inevitable political consequence of having a greatly expanded stock of government net financial assets. Protecting the value of those net financial assets entails maintaining the economy in a state of depression and wealth polarization such that that stock is never drawn down and spent.

Bill –

That is a load of rubbish and you know it! Had Australia not been running surpluses, or even been running smaller surpluses, interest rates would have been higher but unemployment and underemployment rates would have been just as bad.

“To some extent MMT is supposed to be describing what is actually happening rather than what we hope for”

MMT *only* describes what happens.

The fundamental behaviours are what happen in monetary economies. The power of the theory is that it can be used by all *political* persuasions to guide their philosophy.

Your concern over stocks of financial assets is a political position, not an economic one. There is no economic effect from large lumps of financial assets unless they are spent.

There is a very simple solution to anybody deploying financial assets to buy what they want. The state simply has to outbid them.

If we want politicians that can’t be bought off, then we have to buy them off ahead of time. That means publicly funded political parties and jail for anybody trying to use money to influence politicians or hire them after they leave office.

But those are political issues to do with the integrity of our democracy. They are not a function of the monetary system.

Stone,

“If you focussed tax on poor people and absolved from tax anyone with an annual income over a million dollars or assets over ten million dollars then when there was a recession and working class people lost their jobs, you would get a big drop in tax take.”

You may be forgetting that a more pronounced effect on demand during recessions comes from people moving from higher paid roles to lower paid roles or fewer hours- so it’s not just about unemployment.

In that sensario, tax liabilities fall faster than income, as people move from higher tax brackets to lower ones.

@Neil Wilson, “Your concern over stocks of financial assets is a political position, not an economic one. There is no economic effect from large lumps of financial assets unless they are spent.”

We now have austerity because the large stocks of financial assets have empowered a constituency that needs to maintain the value of those stocks of financial assets by ensuring that they are not spent. If you say that our current state of austerity is not an economic effect then more fool you.

Are you saying that “we” need to get into a bidding war with the banks as a way to ensure decent political leadership? To me that sums it up. You say we need to bring the law to bear to make sure we have no corruption. That is so naive. The law serves and follows money. It always has done and probably always will. We only get equitable laws and politics when we have less extreme wealth inequality. Those with the money make the rules.

Either Bill disagrees with what you have written or MMT is bunk IMO. Trying to claim that it is possible to have economics separated away from politics is either deluded or dishonest IMO.

@CharlesJ

I see what you mean now about how income tax brackets make the automatic stabilizers more effective. It is also true though that the most wealthy consume as much as they want anyway (they have ample money such that incremental changes have no effect on their consumption) so from an aggregate demand management perspective there is no point in taxing them at all. You will not increase CPI inflation even if you give every billionaire another few billion. That is not to say that it is not vital that they don’t get given another few billion- it is simply that the malign effects that would come from doing so are due to effects on financial and political power and fragility of the financial system (asset bubbles, commodity price spikes/crashes etc) not from direct effects on aggregate demand.

” We only get equitable laws and politics when we have less extreme wealth inequality. Those with the money make the rules.”

If your conclusion is true, then your premise is impossible to achieve and you may as well give up now.

Neil Wilson, I don’t think it is impossible to achieve. The people with the money may be persuaded just as slavery was abolished not out of self interest but out of a sense of humanity. Also of course if things carry on as they are then we could run into a nasty situation where the wealthy lose wealth due to everything breaking down. Self interest may cause the wealthy to want to avoid that. It seems to me far more attractive to live as part of a content prosperous community than to be in some fortress living like a third world despot.

@Neil Wilson, the key point is that when you have great disparities of wealth and power, those with the wealth and power MAY on occasions act magnaminously. When you don’t have those disparities the issue never arises. People just get on with things and things are equitable because they are.

“@Neil Wilson, the key point is that when you have great disparities of wealth and power, those with the wealth and power MAY on occasions act magnaminously”

The key point is that is what you believe. That doesn’t necessarily mean that is the case – or that sufficient people agree with you.

“People just get on with things and things are equitable because they are.”

Except those people who believe they should have wealth and power – who will then work to undermine that structure just as they have done successfully before.

Sorry, but that is dream land that just isn’t supported by history. You have to take the ‘wealth and power’ with you by showing them how much better off they are in absolute terms even if they are relatively less wealthy. And if that means allowing them a large spreadsheet number somewhere for them to admire, so be it.

@Neil Wilson, again if you think “large spread sheet numbers” don’t warp our whole economy, political and social system -then more fool you.

The real economy is heading towards merely being a charity case for those private institutions and individuals who have “large spread sheet numbers”. A large stock of risk free financial assets shields those holding them from any concern about whether the real economy produces anything much. Even if there is a huge level of unemployment and most factories get mothballed, those with the risk free financial assets know that they will be entitled to what little still gets produced. The pointless shortages get born by those without the risk free financial assets and so are of little political concern. The evidence I see in front of my eyes is that is happening already.

“The evidence I see in front of my eyes is that is happening already.”

Then you can politically agitate for what you believe in.

But that doesn’t alter the economics that large stocks of financial assets are inert and that a state can, if it chooses, stop that having any effect.

The issue has nothing to do with large spreadsheet numbers. The issue is control of the state. And there is more than one way to skin that particular rabbit.

@Neil Wilson, you talk about “the state” as if it were not something that gets directed by those with financial power. The financial system is a political construct and the political system is molded by and for the financial system. It is all the same soup.

@Aidan: “That is a load of rubbish and you know it! Had Australia not been running surpluses, or even been running smaller surpluses, interest rates would have been higher but unemployment and underemployment rates would have been just as bad.”

Bill very likely isn’t going to answer this because he spends a lot of time on this blog explaining precisely why this is wrong, but perhaps you’d like to take a stab at explaining why you think so?

Dr Zen – maybe you’d care to point out some examples – if Bill really does spend a lot of time explaining why that’s wrong, it shouldn’t be too hard!

I don’t recall a single example of Bill explaining why that’s wrong. I do recall him explaining that government spending has the advantage of being able to be targetted (a valid point) and that he thought private debt was too high (his personal bias) but neither of these factors suggest the RBA wouldn’t respond by raising interest rates until unemployment and underemployment were just as bad.

“as if it were not something that gets directed by those with financial power. ”

And you talk as if it is *only* directed by those with financial power – in which case your cause is already lost as I’ve pointed out.

Attacking those with financial power too hard when they have influence over the control levers at the moment is a sure fire way of getting nowhere politically. I find it amazing you struggle to see that.

As I have said the solution is to show that they become better off in absolute terms even if they become worse off relatively as income is equalised.

Trying to drag the top down too much is destructive, smacks of envy and will be stopped in its tracks. Dragging the bottom up is far more egalitarian and politically feasible.

@Neil Wilson

I guess the issue is whether you will be able garner the political support to drag the bottom up. If it is possible to do that whilst allowing “big spreadsheet numbers” to get bigger, then great. I hope that succeeds but I just don’t see that happening. I wouldn’t care about “big spreadsheet numbers” if like you I thought that that was all they were.

My guess is that your economics will create politics that will thwart it from being implemented. This discussion is really about politics. You are saying that it is politically harder to tax assets than it is to run deficits. I am saying that once accumulated deficits have created a sufficient stock of risk free financial assets, it is harder to run continued deficits than to tax assets. It basically rests on how stupid you take those holding the risk free financial assets to be. Your view as to the most politically expedient course of action seems to me to depend on the assumption that they are idiots. Why would they take any risk of inflation when they personally have plenty of wealth to tide them and their heirs over for perpetuity?

The balance of political difficulties shifts with time as the stock of risk free financial assets grows and so changes the nature of the game. I’m saying sort things out whilst we still can. My guess is that if we don’t we will just get a stultifying permanent system of austerity and then perhaps somewhere else in the world a working system will set up and the current developed world will then be the third world in that world order. Argentina was an extremely wealthy country in 1900. India led the world in technology and mathematics three thousand years ago.

Realising that PBO’s band terms of trade is not related to Treasury’s GDP which is used as the denominator in the structural budget balance/GDP ratio (figure 1 above) I start wondering what the fuss in the media is about when such simple but serious shortcoming is not seen by the peer reviewers and the economics journos. Going through the way potential output is defined and the Cobb-Douglas framework is “used” in the paper I just think that more serious work is needed for the paper being used in budgetary decisions. Thank you for spending time to go through all the “technicalities” of the paper.