Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

Saturday Quiz – June 1, 2013 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for yesterday’s quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of modern monetary theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

The National Accounting framework says that total spending is the sum of household consumption, private investment, government spending and net exports. To understand this in terms of a stock-flow consistent macroeconomics, where we have to always trace the impact of flows during a period on the relevant stocks at the end of the period, we would interpret the spending components as flows adding to the stock of aggregate demand which in turn impacts on the final production (Gross Domestic Product).

The answer is False.

This is a very easy test of the difference between flows and stocks. All expenditure aggregates – such as government spending and investment spending are flows. They add up to total expenditure or aggregate demand which is also a flow rather than a stock. Aggregate demand (a flow) in any period and determines the flow of income and output in the same period (that is, GDP).

So while flows can add to stock – for example, the flow of saving adds to wealth or the flow of investment adds to the stock of capital – flows can also be added together to form a larger flow (for example, aggregate demand).

Question 2:

The imposition of positive minimum reserve requirements on the private banks by the central bank, will have no constraining influence on the credit creation activities of the private banks relative to a system where there are no requirements other than the rule that reserve balances have to be positive.

The answer is True.

While many nations do not have minimum reserve requirements other than reserve account balances at the central bank have to remain non-zero, other nations do persist in these gold standard artefacts. The ability of banks to expand credit is unchanged across either type of country.

These sorts of “restrictions” were put in place to manage the liabilities side of the bank balance sheet in the belief that this would limit volume of credit issued.

It became apparent that in a fiat monetary system, the central bank cannot directly influence the growth of the money supply with or without positive reserve requirements and still ensure the financial system is stable.

The reality is that every central bank stands ready to provide reserves on demand to the commercial banking sector. Accordingly, the central bank effectively cannot control the reserves that are demanded but it can set the price.

However, given that monetary policy (mostly ignoring the current quantitative easing type initiatives) is conducted via the central bank setting a target overnight interest rate the central bank is really required to provide the reserves on demand at that target rate. If it doesn’t then it loses the ability to ensure that target rate is sustained each day.

Imagine the central bank tried to lend reserves to banks above the target rate. Immediately, banks with surplus reserves could lend above the target rate and below the rate the central bank was trying to lend at. This would lead to competitive pressures which would drive the overnight rate upwards and the central bank loses control of its monetary policy stance.

Every central bank conducts its liquidity management activities which allow it to maintain control of the target rate and therefore monetary policy with the knowledge of what the likely reserve demands of the banks will be each day. They take these factors into account when they employ repo lending or open market operations on a daily basis to manage the cash system and ensure they reach their desired target rate.

The details vary across countries (given different institutional arrangements relating to timing etc) but the operations are universal to central banking.

While admitting that the central bank will always provide reserves to the banks on demand, some will still try argue that by the capacity of the central bank to set the price of the reserves they provide ensures it can stifle bank lending by hiking the price it provides the reserves at.

The reality of central bank operations around the world is that this doesn’t happen. Central banks always provide the reserves at the target rate.

So as I have described often, commercial banks lend to credit-worthy customers and create deposits in the process. This is an on-going process throughout each day. A separate area in the bank manages its reserve position and deals with the central bank.

The two sections of the bank do not interact in any formal way so the reserve management section never tells the loan department to stop lending because they don’t have reserves. The banks know they can get the reserves from the central bank in whatever volume they need to satisfy any conditions imposed by the central bank at the overnight rate (allowing for small variations from day to day around this).

If the central bank didn’t do this then it would risk failure of the financial system.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Oh no – Bernanke is loose and those greenbacks are everywhere

- Building bank reserves will not expand credit

- Building bank reserves is not inflationary

- Deficit spending 101 Part 1

- Deficit spending 101 Part 2

- Deficit spending 101 Part 3

Question 3:

If the external sector is in deficit overall and GDP growth rate is faster than the real interest rate, then:

(a) Both the private domestic sector and the government sector overall can pay down their respective debt liabilities.

(b) Either the private domestic sector or the government sector overall can pay down their debt liabilities.

(c) Neither the private domestic sector or the government sector overall can pay down their debt liabilities.

The answer is (b) Either the private domestic sector or the government sector overall can pay down their debt liabilities..

Once again it is a test of one’s basic understanding of the sectoral balances that can be derived from the National Accounts. Some people write to me in an incredulous way about the balances.

The answer is Option (b) because if the external sector overall is in deficit, then it is impossible for both the private domestic sector and government sector to run surpluses. One of those two has to also be in deficit to satisfy the accounting rules.

It also follows that it doesn’t matter how fast GDP is growing, if a sector is in deficit then it cannot be paying down its nominal debt.

To understand this we need to begin with the national accounts which underpin the basic income-expenditure model that is at the heart of introductory macroeconomics.

We can view this model in two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of spending; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the income produced. Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances.

So from the sources perspective we write:

GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

From the uses perspective, national income (GDP) can be used for:

GDP = C + S + T

which says that GDP (income) ultimately comes back to households who consume (C), save (S) or pay taxes (T) with it once all the distributions are made.

So if we equate these two perspectives of GDP, we get:

C + S + T = C + I + G + (X – M)

This can be simplified by cancelling out the C from both sides and re-arranging (shifting things around but still satisfying the rules of algebra) into what

we call the sectoral balances view of the national accounts.

(I – S) + (G – T) + (X – M) = 0

That is the three balances have to sum to zero. The sectoral balances derived are:

- The private domestic balance (I – S) – positive if in deficit, negative if in surplus.

- The Budget Deficit (G – T) – negative if in surplus, positive if in deficit.

- The Current Account balance (X – M) – positive if in surplus, negative if in deficit.

These balances are usually expressed as a per cent of GDP but that doesn’t alter the accounting rules that they sum to zero, it just means the balance to GDP ratios sum to zero.

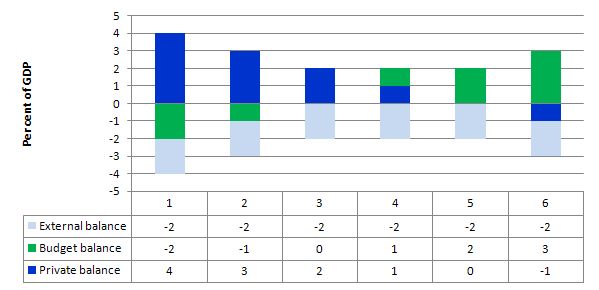

Consider the following graph and associated table of data which shows six states. All states have a constant external deficit equal to 2 per cent of GDP (light-blue columns).

State 1 show a government running a surplus equal to 2 per cent of GDP (green columns). As a consequence, the private domestic balance is in deficit of 4 per cent of GDP (royal-blue columns). This cannot be a sustainable growth strategy because eventually the private sector will collapse under the weight of its indebtedness and start to save. At that point the fiscal drag from the budget surpluses will reinforce the spending decline and the economy would go into recession.

State 2 shows that when the budget surplus moderates to 1 per cent of GDP the private domestic deficit is reduced.

State 3 is a budget balance and then the private domestic deficit is exactly equal to the external deficit. So the private sector spending more than they earn exactly funds the desire of the external sector to accumulate financial assets in the currency of issue in this country.

States 4 to 6 shows what happens when the budget goes into deficit – the private domestic sector (given the external deficit) can then start reducing its deficit and by State 5 it is in balance. Then by State 6 the private domestic sector is able to net save overall (that is, spend less than its income).

Note also that the government balance equals exactly $-for-$ (as a per cent of GDP) the non-government balance (the sum of the private domestic and external balances). This is also a basic rule derived from the national accounts.

Most countries currently run external deficits. The crisis was marked by households reducing consumption spending growth to try to manage their debt exposure and private investment retreating. The consequence was a major spending gap which pushed budgets into deficits via the automatic stabilisers.

The only way to get income growth going in this context and to allow the private sector surpluses to build was to increase the deficits beyond the impact of the automatic stabilisers. The reality is that this policy change hasn’t delivered large enough budget deficits (even with external deficits narrowing). The result has been large negative income adjustments which brought the sectoral balances into equality at significantly lower levels of economic activity.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

I have a small difficulty with the sectoral balance equation, which concerns the definition of government spending G. In the definition of the GDP, G does not include transfer payments (pensions and other welfare payments) and that appears reasonable if GDP is intended to represent economic activity. However, this must mean that the sectoral balance equation needs to be modified to include transfer payments.

Bill, I think it might be better pedagogically if the three categories mirrored those in the table and also color coded when initially defined. This should aid the memory and assist the student in comparing the table with the preceding discussion, in the best of all possible worlds.

Q2, “While many nations do not have minimum reserve requirements other than reserve account balances at the central bank have to remain non-zero”

1) Can it be zero?

2) non-zero (as in negative)???

Q2, “some will still try argue that by the capacity of the central bank to set the price of the reserves they provide ensures it can stifle bank lending by hiking the price it provides the reserves at.

The reality of central bank operations around the world is that this doesn’t happen. Central banks always provide the reserves at the target rate.”

I believe the some will say the central bank will change the overnight target rate.

I have a question about the transfer payment that Tony referenced. I read a good piece on this at Levy institute and was wondering if it were not simpler to just discuss spending and later taxing for the purposes of accounting identity. I understand the transfer portion but that seems to muddy the issue. Am I out to lunch on this? Thanks for any help guys.