It's Wednesday and I discuss a number of topics today. First, the 'million simulations' that…

In a few minutes you do not learn much

There was an article in the New York Times at the weekend – Warren Mosler, a Deficit Lover With a Following – which seems to have attracted some attention. The attention has spanned from the vituperative personal attacks on the article’s subject, all of which would seem to be factually in error, to claims that proponents of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) are “just nuts”. The latter assessment apparently was drawn after a few minutes consideration by a US economist. I don’t think one learns very much in a few minutes. But the output over the years of the particular economist quoted by the NYTs tells me he hasn’t learned much after presumably many hours of study. I suppose that if you are mindlessly locked into the mainstream macroeconomics textbook models then that is to be expected.

Dr Thoma was the mainstream stooge quoted by the NYTs article as its parting shot – to let the readers know that MMT is not a rival to the robust mainstream theories that dominate and have created a fanatical following of the likes of Dr Thoma. You can read what he said presently.

But a few reflections set the scene. In this 2010 piece – Should You Be Worried About Inflation? What About Deflation? – Dr Thoma was trying sound erudite when he tried to wrestle his belief in the textbook model of a money multiplier with the real world evidence that in fact no such relationship actually exists in any meaningful (or operational) way.

Under the heading “The Fed’s Control of the Money Supply”, he claimed that the money supply is determined (that means in a causal sense) by the (multiplier) x (Monetary Base).

He wrote:

To control the money supply, the Fed takes the multiplier as given, and then sets the MB at a level that gives it the Ms it desires (the Fed estimates the multiplier daily).

He cannot have read the article that appeared in the September 2008 edition of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York Economic Policy Review there was an interesting article published entitled – Divorcing Money from Monetary Policy.

That article demonstrated why the account of monetary policy in mainstream macroeconomics textbooks (such as presented by Dr Thoma) from which the overwhelming majority of economics students get their understandings about how the monetary system operates is totally flawed. This is the stuff that Mark Thoma also pumps out into cyber space as some sort of truth.

In relation to his view of the the way the banking system operates, I may use an expression he will be familiar with – I think it’s just nuts.

The FRBNY article states clearly that:

In recent decades, however, central banks have moved away from a direct focus on measures of the money supply. The primary focus of monetary policy has instead become the value of a short-term interest rate. In the United States, for example, the Federal Reserve’s Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) announces a rate that it wishes to prevail in the federal funds market, where overnight loans are made among commercial banks. The tools of monetary policy are then used to guide the market interest rate toward the chosen target.

This is practice is not confined to the US. All central banks operate in this way and I have shown in other blogs that central banks cannot control the “money supply”.

Please read my blog – Money multiplier and other myths – for more discussion on this point.

Dr Thoma’s article in fact attracted a lot of comments on his Dr Thoma’s own site, – ONE – of which cross-referenced my own blog and basically said Thoma didn’t know what he was talking about. That comment was supported by several others.

Thoma’s reply was illustrative.

First, he said that:

… If you think the multiplier hasn’t changed, I’d suggest looking at the graph of it at FRED to disabuse yourself of that notion …

Here is the latest Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis’ estimate of their – M1 Multiplier – which is “the ratio of M1 to the St. Louis Adjusted Monetary Base”.

If one is postulating a causal relationship between the monetary base and the money supply mediated by this so-called multiplier then it is usual to expect the coefficient (the multiplier) to be stable. It has not been stable and serves no useful basis for predicting anything.

In the article Dr Thoma offered the following explanation by way of reassurance:

The multiplier falls when excess reserves increase, and the dramatic increase in excess reserves during the crisis has caused the multiplier to fall substantially, enough to offset the increase in MB. The result is that the quantity of money actually circulating in the economy, (mult)(MB), has remained relatively constant.

So Dr Thoma, a bit adrift without his textbook models to fall back on, assured us all (3 years ago) that the absence of the multiplier is only temporary and it will be back before we know it.

The problem with all these explanations of the “disappearing” money multiplier that have permeated the literature in the last 4 years as the textbook model has been exposed as being “nuts”, is that they are just made up.

They are ad hoc defenses of a flawed theory, which remind me of the message that David M. Gordon (in his great 1972 book – Theories of poverty and underemployment, Lexington, Mass: Heath, Lexington Books) wrote about in relation to neoclassical human capital theory.

Gordon said that mainstream economists continually responded to empirical anomalies with these ad hoc or palliative responses.

So whenever the mainstream paradigm is confronted with empirical evidence that appears to refute its basic predictions it creates an exception by way of response to the anomaly and continues on as if nothing had happened.

The question that is always unanswered and applies in this case just as strongly is – were students in Dr Thoma’s classes ever provided with conceptual tools that would allow them to appreciate the time series showed in the graph above? Which textbook tells us that the “multiplier” is a moving feast, which can plunge at any time?

The answer is that none of the mainstream macroeconomics textbooks provide any insight into these questions. They just assert that the central bank controls the money supply via its manipulation of the monetary base.

This relates to the second response that Dr Thoma gave to the commentator on his blog:

I understand full well that there is a small, but *very noisy* group of people who think they have a better monetary theory than that found in standard textbooks and in economics journals. When people I respect a lot have looked at this theory, they have found it wanting and my own reading of this work accords with that conclusion. So go ahead and make your points, but don’t act like I’m making some egregious error by adopting the standard, well-tested, and accepted theoretical structure over the new one that most people reject, one that I find comes up short in many ways. We may all be wrong, time will tell, but for now that’s how it is. This theory has a secondary place in the literature (at best, that’s way too generous). I’m sorry to see that you – an admitted amateur with no ability to discern finer points – has been taken in.

I think time has told. The question is who has the “ability to discern finer points”?

Those “very noisy” characters were Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) proponents.

Should I add that none of the “standard textbooks” or articles in standard “economics journals” went close to providing a conceptual framework for predicting the monetary events that have transpired in the last five years or so. Not a single one.

The mainstream approach initially predicted:

1. Rising interest rates as deficits rose.

2. Inflation as the monetary bases of central banks sky-rocketed.

3. There would be a massive surge in loans because banks loan out reserves.

Then when none of that happened, the special cases started being trotted out to patch up the deficient theory. The problem is that the special cases negate the theory.

Dr Thoma essentially considered all of things to be realistic threats. MMT considered none of these predictions to have credibility. Some years down the track – who would you give the points to?

Thoma said that:

The worry about inflation is that as the economy begins to recover, banks will begin to loan out their excess reserves. As excess reserves fall, the multiplier will go up driving up the money supply. As noted above, the money supply is related to inflation, and as the money supply goes up so does inflationary pressure.

Well, first following Thoma’s article, the annual rate of growth in the US M2 measure shot up quickly as inflation fell (Source).

But the substantive point is that the mainstream still teach and believe that the commercial banks “loan out their excess reserves” to normal clients, none of whom would have a bank account at the relevant central bank.

Even the Federal Reserve acknowledged this in a July 2009 paper – Why Are Banks Holding So Many Excess Reserves?:

The total level of reserves in the banking system is determined almost entirely by the actions of the central bank and is not affected by private banks’ lending decisions. The liquidity facilities introduced by the Federal Reserve in response to the crisis have created a large quantity of reserves. While changes in bank lending behavior may lead to small changes in the level of required reserves, the vast majority of the newly-created reserves will end up being held as excess reserves almost no matter how banks react. In other words, the quantity of excess reserves depicted in Figure 1 reflects the size of the Federal Reserve’s policy initiatives, but says little or nothing about their effects on bank lending or on the economy more broadly.

This conclusion may seem strange, at first glance, to readers familiar with textbook presentations of the money multiplier … we discuss the traditional view of the money multiplier and why it does not apply in the current environment …

Their conclusion is based on the decision of the central bank to pay the target policy rate on excess reserves. In fact, the inapplicability of the money multiplier is not dependent on whether the central bank does have a support rate in place.

Why is that?

The idea that the monetary base (the sum of bank reserves and currency) leads to a change in the money supply via some multiple is not a valid representation of the way the monetary system operates even though it appears in all mainstream macroeconomics textbooks and is relentlessly rammed down the throats of unsuspecting economic students.

The money multiplier myth leads students to think that as the central bank can control the monetary base then it can control the money supply. Further, given that inflation is allegedly the result of the money supply growing too fast then the blame is sheeted hometo the “government” (the central bank in this case).

The reality is that the central bank does not have the capacity to control the money supply. In the world we live in, bank loans create deposits and are made without reference to the reserve positions of the banks. The bank then ensures its reserve positions are legally compliant as a separate process knowing that it can always get the reserves from the central bank.

The only way that the central bank can influence credit creation in this setting is via the price of the reserves it provides on demand to the commercial banks.

The mainstream view is based on the erroneous belief that the banks need reserves before they can lend and that quantitative easing provides those reserves. That is a major misrepresentation of the way the banking system actually operates. But the mainstream position asserts (wrongly) that banks only lend if they have prior reserves.

The illusion is that a bank is an institution that accepts deposits to build up reserves and then on-lends them at a margin to make money.

The conceptualisation suggests that if it doesn’t have adequate reserves then it cannot lend. So the presupposition is that by adding to bank reserves, quantitative easing will help lending.

But banks do not operate like this. Bank lending is not “reserve constrained”. Banks lend to any credit worthy customer they can find and then worry about their reserve positions afterwards. If they are short of reserves (their reserve accounts have to be in positive balance each day and in some countries central banks require certain ratios to be maintained) then they borrow from each other in the interbank market or, ultimately, they will borrow from the central bank through the so-called discount window. They are reluctant to use the latter facility because it carries a penalty (higher interest cost).

The point is that building bank reserves will not increase the bank’s capacity to lend. Loans create deposits which generate reserves.

The causality is exactly the opposite to Dr Thoma’s equation (in the article cited above) – the central bank has to supply the required reserves. Further, the banks do not lend reserves (except to each other as part of the payments system).

The reason that the commercial banks have not been lending much is because they are not convinced there are credit worthy customers on their doorstep. In the current climate the assessment of what is credit worthy has become very strict compared to the lax days as the top of the boom approached.

Some 7 months earlier (November 25, 2009), Dr Thoma wrote this article which confirms he believes deficits crowd out private spending via interest rate effects – Worries about Budget Deficits and Inflation: Let’s Avoid Repeating Our Mistakes.

Dr Thoma was commenting on the US fiscal stimulus and said:

The worry here is that government borrowing will drive up interest rates, that the increase in interest rates will lower private investment (this is called “crowding out”) and that, in turn, will cause economic growth to be lower that it would be otherwise.

Right now, this is not a very realistic worry. When the economy is near full employment, and when there are not bundles of cheap cash available from the excess savings in countries like China, an increase in government borrowing adds to the competition for the available funds. The increased competition for available savings drives up interest rates and crowds out private investment. But when there is an excess of available funds, as there is now (this is the excess reserves described above), and cheap loans available from foreigners (e.g. from China) – more than the demand for funds at the current interest rate (which is essentially zero) – the government can borrow without putting any upward pressure at all on the interest rate …

This is a reiteration of the mainstream macroeconomics textbook causality that is rejected by MMT.

It is not even necessarily true that higher interest rates lower private investment in a growing economy. Investment decisions compare cost and benefit and when income is growing (as a result of the stimulus and then private spending recovery) even if interest rates are rising so to will be the expected benefits. The textbooks conduct “other things equal” analysis in a static time frame – so they just superimpose a cost increase without considering the income growth.

But that issue is smaller in seriousness to what follows. The implication is that there is a finite savings pool that is the subject of competition from borrowers – public and private. First, saving grows with income and so we say that “investment brings forth its own saving”, which is a way of saying that the income adjustments that occur when aggregate demand change provide a reconciliation between the planned saving and investment.

Second, where do the funds come from that the government borrows? Answer: $-for-$ from the net spending. The government just borrows its own net financial assets back. If you want to profess to understand how the monetary system operates then you have to start with a basic understanding of how net financial assets denominated in the currency of issue enter the banking system in the first place.

Third, the statement “excess of available funds (this is the excess reserves …)” is just nonsensical for reasons discussed above.

Statements like that tell you that Dr Thoma operates in the money multiplier world of the gold-standard textbook and has to continually introduce these ad hoc adjustments when the real world “misbehaves”.

The reserve situation will not influence the ability or the willingness of the banks to lend. That has been one of the fallacies that this downturn has so categorically exposed.

The UK example is manifest. The BoE keeps increasing reserves in the hope that the banks will start lending but the banks will not lend because there is no credit-worthy borrowers (in their estimation) lining up for the loans. If there was they would lend – huge stockpiles of reserves or not.

Fourth, the central bank sets the interest rate at whatever level it desires.

Which brings me to Dr Thoma’s latest outburst concerning MMT.

This relates to the article in the New York Times at the weekend – Warren Mosler, a Deficit Lover With a Following – which seems to have attracted some attention.

My colleague Randy Wray has responded on issues relating to bias and has corrected known errors in the article, which prejudice the independence of the journalism – see Warren Mosler & MMT: Deficit Lovers?.

I won’t deal with those issues – although they are important.

The right-wing (anti-NYTs) lobby chimed in with articles like this – New York Times’ Puff Piece Highlights ‘Deficit Lover With a Following’ – where MMT was referred to as “the far-Left’s most radical economic theories”. That gave me a laugh on Saturday when I read it.

This character didn’t seem to understand that the NYT article was in fact a negative depiction of MMT. But the writer chose to emphasise the one piece of “sanity” in the NYT article and that was provided by Dr Thoma.

Just before comparing MMT to Ron Paul’s gold bug ideas, which have no academic standing or empirical credibility, the NYT article used Dr Thoma as the voice of reason to let people know what the real economists thought of MMT. Here is the relevant paragraph:

“They deny the fact that the government use of real resources can drive the real interest rate up,” said Mark Thoma, an economics professor and widely followed blogger who teaches at the University of Oregon. After delving into the technical details of modern monetary theory for a few minutes, he paused, then added, “I think it’s just nuts.”

There it is.

Dr Thoma is so clever he can take only a few minutes to read at least 40 peer-reviewed articles in the academic journals and several books written by MMT proponents (mostly with Phd degrees in economics) spanning more than 20 years to understand the technical details of MMT.

And in those few minutes he dismisses it totally. Reflect back on Dr Thoma’s own view of the world and how that has stood the test of time.

But lets briefly (I am running out of time) reflect on the single proposition of MMT (so characterised by Dr Thoma) that is “just nuts”.

The proposition is that government’s use of real resources can drive the real interest rate up.

First, what is the real interest rate? Most people will have an idea of what the nominal interest rate is. It is the amount of money that we pay on loans.

The real interest rate is the nominal interest rate minus the expected inflation rate. So there is not one real interest rate but a myriad of them depending on the horizon we adopt for the expected inflation.

Second, it is a composite of two separate time series and can change due to relative movements in each of those components. So if nominal interest rates were constant and inflationary expectations rose (fell) the real interest rate would fall (rise).

Equally, if the nominal interest rate rose but inflationary expectations fell (perhaps because people expected economic activity to stall as a result of declining investment) then the real interest rate might rise or fall depending on the relative strength of these offsetting factors.

So to argue that a rising command of public real resource use drives up the real interest rate then the nominal interest rate has to rise faster than expected inflation because of the a rising budget deficit as a percentage of GDP.

How would that occur?

The normal arguments are dealt with above in the discussion of crowding out. If there is a finite supply of funds to the market and governments and non-government borrowers compete for these funds then the interest rate goes up. Why does it go up faster than inflationary expectations – that question is not definitively answered in this theory.

It is clear that governments really only borrow back the funds they have created when running deficits. But what about the empirical world?

How do MMT propositions rate against those of Dr Thoma?

The Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland provides the most current series on inflationary expectations and the real interest rate that is available.

In October 2009, the Bank released a discussion paper outlining – A New Approach to Gauging Inflation Expectations. It is a non-technical version of this 2007 paper – Inflation Expectations, Real Rates, and Risk Premia: Evidence from Inflation Swaps.

You can get the latest data – HERE.

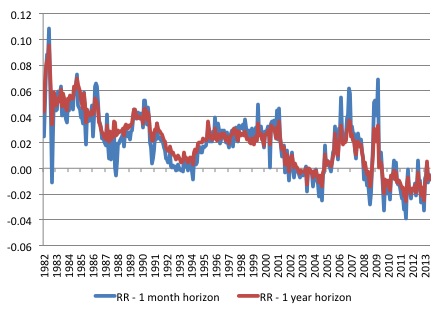

The data spans the period from January 1, 1982 to June 1, 2013. The following graph shows the evolution of their measure of the real interest rate in the US s period for inflation expectations 1-month ahead horizon (blue line) and the 1-year ahead forecasts (red line).

Is there are cyclical pattern? Not likely. The literature has found real interest rates to be broadly acyclical or if anything counter-cyclical.

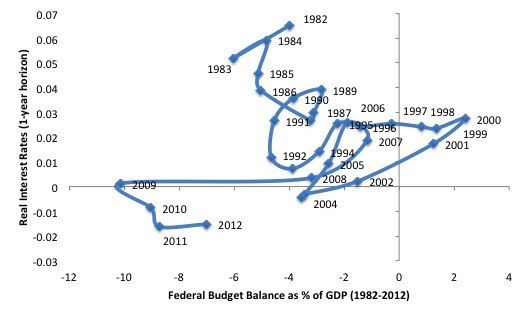

What has been the relationship between the US federal deficit and the real interest rate looks like. The deficit data comes from FRED2. The real interest rate is the average of the monthly observations.

It is hard to mount an argument that rising deficits (movements to the left along the horizontal axis) increase real interest rates.

Conclusion

That is all I have time for today. I will come back to the real interest rate question again once I had done some more sophisticated modelling and decomposed the movements in it for the US data. Any scatter plot has to be treated with caution and do not prove anything.

But the bottom line is that it might have only taken Dr Thoma a “few minutes” to come to his conclusion but in those few minutes he learned what one usually does in few minutes – hardly anything at all.

In fact, his written output over the years tells me he has hardly learned anything that is not in the mainstream macroeconomics textbooks, which time has told us is basically non-knowledge.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

But when there is an excess of available funds, as there is now (this is the excess reserves described above), and cheap loans available from foreigners (e.g. from China) – more than the demand for funds at the current interest rate (which is essentially zero) – the government can borrow without putting any upward pressure at all on the interest rate …

Strange quote from Thoma. It begins with worry about markets driving up rates as loanable funds are depleted and ends with an admission the Fed controls the interest rate. Does he not understand what he’s talking about or is his thinking so mixed up he believes both?

“So whenever the mainstream paradigm is confronted with empirical evidence that appears to refute its basic predictions it creates an exception by way of response to the anomaly and continues on as if nothing had happened.”

Epicycles.

Just like those who believed that the earth was the centre of the universe.

“Banks lend to any credit worthy customer they can find and then worry about their reserve positions afterwards.” Strikes me that even that overestimates the need that commercial banks have for reserves.

I.e. if a central bank disappeared and all reserves or monetary base just vanished, then commercial banks would simply find other ways of settling up with each other. E.g. they’d let inter bank debts say in place for longer, and if a particular bank got too far into debt with other banks, the latter would demand payment in the form of shares, property or whatever the debtor bank had to offer.

That wouldn’t be as convenient as the standard settling up system offered by central banks in most countries, but it would work.

Dear Billy,

I think you misunderstood the quotation above. I think “delving into details for a few minutes” amounts to re-checking what MMT says once more.

I remember he was having some public discussion with MMT proponents before. So, he must be aware of MMT work and must have delved into MMT for more than few minutes. Not that would make a difference, but…

On a second thought, I just remembered what thoma had to say (write in his blog) about Marxian labour theory of value. He wrote

When I saw this, It was clear to me that he did not read a single line of Marx’s work. He, nonetheless, asserted without any qualifications as it was invalid. It is pathetic, indeed.

On top of that, a better title would have been that Mr Mosler, if I may say, is deficit “indifferent”, not lover.

” if a particular bank got too far into debt with other banks, the latter would demand payment in the form of shares, property or whatever the debtor bank had to offer.”

Or they would just not offer payment between banks and require each individual to have an account with every bank.

Always remember that unless there is another mechanism in place for bank B to receive a payment from Bank A, Bank B has to become the replacement depositor in Bank A.

Inevitably you end up with a clearing house and then eventually, after a few payment system crises, a central clearing bank – as the history of banking has shown time and again,

In a modern world the payment system is more important than ever, and simply can’t be left to private concerns – any more than note printing was in previous times.

On the fourth of July, Lowrey also published a piece on Mosler setting out a Mosler reading list. The interesting feature of this article is the nature of most of the comments, many of which are supportive of MMT and some of which show a familiarity with some of its ancestral history and its current advocates, like Bill, Randy Wray, and Stephanie Kelton. Some of the comments are worth a read, such as the one touching on the debate between Mosler and Robert Murphy, a deficit hawk. Here is the link: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/07/04/warren-mosler-a-reading-list/.

This may be the New York Times on a Keynesian kick. Here are two links to historically oriented discussions of Keynes by a policy-maker under Reagan and Dubya, Bruce Bartlett, who is sympathetic to Keynes and certainly more sophisticated than Ferguson, whose personal comments about Keynes are disgraceful and, moreover, historically misleading – he “forgot” that Lydia had suffered a miscarriage.

http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/05/14/keynes-and-keynesianism/;

http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/05/07/keyness-biggest-mistake/.

The NYT gave links to Mosler’s writings, what more can we ask for at this stage? I think Wray and Bill Black are needlessly incensed that they misrepresented MMT. First step is better than none.

Bill –

Haven’t you previously said it could also do so by setting a positive overnight interest rate?

And surely that amounts to controlling the money supply? Indirect control, but control nonetheless.

I agree with RonT. Any piece that gets Warren\’s name, Stephanie\’s name and Jamie\’s name in the New York Times, all on the same day, is a good piece. We should remember our Gandhi – when they stop ignoring us and start hurling their derisive laughter and scorn at us instead, it means we\’re finally making real progress. We should gird what loins we can – *much* worse abuse is surely coming.

As for the good Ms. Lowrey\’s particular animus toward MMT, Randall Wray mused (in his own response to her article) that a certain Prominent Princetonian – and NYT colleague – might be bending her ear. I think there\’s a simpler explanation. According to her Wikipedia page, Ms. Lowrey is married to Ezra Klein, who was visibly annoyed over the Platinum Coin idea when it came up. He considered it undignified, as I recall, and dismissed those who proposed it as fringe elements.

Coincidence?

The NYT has also reported the Dept of Education’s test of economic literacy that they think a 12 year old should know, with answers. One of the questions concerns interest rates.

http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/04/24/test-your-economic-literacy/

Haven’t you previously said it could also do so by setting a positive overnight interest rate?

Aidan

Same thing isn’t it ? And I don’t think it can ‘control’ the money supply directly or indirectly.

The late Hans Jürgen Eysenck, in discussing the experimental work of Leon Festinger and James Carlsmith on dissonance, concluded:

He might have added economics to his list.

It is not surprising that orthodox economists , when confronted with empirical data that conflicts with their theories, just have to explain away the data in some way that reduces or eliminates the unease arising from their state of cognitive dissonance. Some may explain the data away as being the result of, for example, ‘a special case’; others may just resort to abuse. The latter belong to the ‘Nuts’ school of criticism.

The NYT coverage was a huge coup for MMT, even through it was “fair and balanced” in the sense of Faux News. Regardless, its millions of $ worth of free PR.

Of course, those who objected legitimately were right to do so. That provides the opportunity to set the record straight and garner even more free PR.

So huge net positive for MMT and more evidence that the last mile is closing. Keep up the good work and don’t relax the pressure.

@Brian Lilley

Ackerlof has been influenced by Festinger’s theory of cognitive dissonance. And the situation is more complex than Eysenck alludes to in the quote. For a simple instance, at the time that Festinger enunciated cognitive dissonance theory, everyone agreed that people generally experienced pre-decision dissonance. The original contribution was the hypothesizing of post-decision dissonance supported by ingenious experiments and field studies, the most famous of the latter being When Prophecy Fails.

One word can sum up why the mainstream text books and Dr Thoma don’t understand the money supply process.

SECURITISATION!!!!!!!!!

Tom H. – awash in good old horse sense.

I think that “delving into details for a few minutes” is (polite) NYT jargon for “the interviewed person fell asleep during the interview”. That would explain it, wouldn’t it?

Brian:

Here is an article you really should read:

http://www.cracked.com/article_19468_5-logical-fallacies-that-make-you-wrong-more-than-you-think.html

About the true nature of human reasoning (very funny too).

#5. We’re Not Programmed to Seek “Truth,” We’re Programmed to “Win”

#4. Our Brains Don’t Understand Probability

#3. We Think Everyone’s Out to Get Us

#2. We’re Hard-Wired to Have a Double Standard

#1. Facts Don’t Change Our Minds

It’s sad to realize how true these are.

Here’s the internet archive version of that now-unavailable CBS News article:

http://web.archive.org/web/20170511200009/http://www.cbsnews.com/news/should-you-be-worried-about-inflation-what-about-deflation/