It’s Wednesday and I just finished a ‘Conversation’ with the Economics Society of Australia, where I talked about Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and its application to current policy issues. Some of the questions were excellent and challenging to answer, which is the best way. You can view an edited version of the discussion below and…

The IS-LM framework – Part 1

I am now using Friday’s blog space to provide draft versions of the Modern Monetary Theory textbook that I am writing with my colleague and friend Randy Wray. We expect to complete the text during 2013 (to be ready in draft form for second semester teaching). Comments are always welcome. Remember this is a textbook aimed at undergraduate students and so the writing will be different from my usual blog free-for-all. Note also that the text I post is just the work I am doing by way of the first draft so the material posted will not represent the complete text. Further it will change once the two of us have edited it.

NOTE: Randy and I discussed at length how much mainstream analysis we would include in the textbook. Clearly, we have a responsibility to provide students with an understanding of the tools that are used in the profession including those that are frequently referred to in the policy debate.

As you will see from the Table of Contents (information below), I think we have been fairly generous in how much of the mainstream material, which we see as having no analytical veracity or policy relevance, we have included.

This Chapter is about IS-LM analysis, a framework we also reject outright. However, during the current crisis, it has been used by notable economists who have held it out as an approach that still has relevance. In that vein we have decided to include it as a separate chapter even though, at first, we had excluded it from the book.

However, we don’t go the next step and derive and utilise the full AD-AS model that flows from the IS-LM approach and is the main organising framework for the orthodox exposition.

The homePage for the Textbook is now available but the material is still being added and the site won’t be fully functional for some months yet. We have nearly agreed on the Table of Contents, which defines the order of exposition of the pedagogy. You can find the site at http://www.mmtonline.net and the Table of Contents is available there.

Note I still haven’t finished the British-IMF Case Study but the sequencing needs for a class that is using the book this semester requires I get the IS-LM Chapter completed first – over the next couple of weeks.

Chapter 16 – The IS-LM Framework

16.1 Introduction

Soon after the publication of Keynes’s General Theory, British economist J.R. Hicks published an article that attempted to integrate the insights he felt were useful in the General Theory with those of the so-called “Classics” that Keynes had opposed. We discussed the debate between Keynes and the Classics in Chapter 15.

The so-called Neo-classical synthesis that emerged and dominated macroeconomic thinking, particularly the textbook expositions, was built on the work of J.R. Hicks and his IS-LM model (see box for more discussion).

The IS and LM curves are the equilibrium relationships pertaining, respectively, to the product (goods) market (investment = saving) and the money market (demand for money (liquidity preference) equals money supply).

The representation of the goods market equilibrium in terms of simple equality between investment and saving reflected the historical period that the model was developed – the simplifying assumption was that we would gain essential insights into income determination by assuming a closed economy without government.

The IS equation was subsequently extended to allow for the impact of governments and net exports on aggregate demand.

The income-expenditure model we considered in Chapter 12 allowed the interest rate to impact on investment and hence aggregate demand and output in the goods market. The interest rate was considered to be determined by the equality of money demand and supply in the money market.

The IS-LM approach thus was built on the interdependence of the equilibrium states in the two markets. The general IS-LM approach showed how the equilibrium solution for output (employment) and the interest rate was simultaneous. We needed to know what the interest rate was to solve the level of income and the level of income to solve the interest rate.

In an analytical sense, there were two unknowns – output and the interest rate – and two equations to allow us to solve the unknowns.

The IS-LM model is an early example of a general equilibrium model that remains fashionable in mainstream economics.

16.2 The LM Curve

We assume that the price level is constant. The IS-LM model allows us to introduce price level changes but at present we are operating in real terms.

Money market equilibrium requires that the demand for money equal the supply. We use the term money demand to refer to the willingness to hold cash balances as part of a wealth portfolio.

The demand for money – or as Keynes called it – the liquidity preference – is a function of the level of income and the interest rate.

Three motives have been identified for holding liquid balances (money) in preference to other assets:

- Transactions motive – people need money to engage in daily transactions. Thus the demand for liquidity will be some proportion of total national income.

- Precautionary motive – at times major events occur that need to be resolved through transactions – for example, maintaining a cash balance to pay for engine repairs on a car. This motive also tends to vary with national income as the higher is the level of economic activity, the higher are the overall transactions.

- Speculative motive – Keynes contribution, which we considered in Chapter 15 was to highlight that money is not simply a means of exchange. People used money in times of uncertainty over movements in interest rates. They have a choice between holding money which earns no interest return or purchasing an interest-bearing asset, which has less liquidity. Keynes juxtaposed the decision to hold money or bonds. If the interest rate is expected to rise, the price of bonds falls and capital losses would be expected. So at lower interest rates more people would prefer to hold money than take a chance that they would lose should they invest in bonds. Alternatively, if the interest rate falls, the price of bonds rises and capital gains would be enjoyed. At higher interest rates, more people will form the view that rates will fall rather than rise and the liquidity preference will be lower.

The other way of thinking about the impact of interest rates is to realise that the opportunity cost of holding money rises when interest rates are higher because holding money negates the alternative of holding an interest-earning asset.

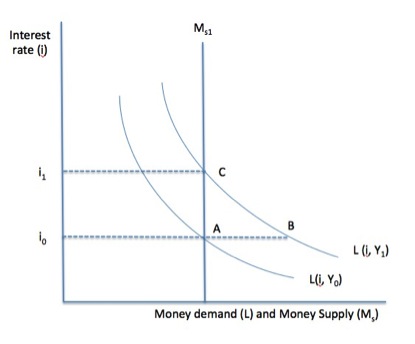

Figure 16.1 shows the liquidity preference function for a range of income levels. The nominal rate of interest is on the vertical axis and the volume of money demand is on the horizontal axis.

The money demand curve (L) is downward sloping with respect to the interest rate and shifts outwards at higher income levels (Y1 < Y2).

The higher is the interest rate, the lower will be the demand for liquidity, other things equal. However, at any interest rate, the higher is the level of national income, the higher will be the demand for money.

The money demand curve is smooth and non-linear because of diversity of opinion. For example, as interest rates rise, wealth holders progressively form the view that they have reached their maximum. Eventually everybody adopts the same expectation.

The money supply (Ms) is assumed to be controlled by the central bank via the monetary base and the money multiplier determines the quantity of money supplied for a given base.

We can thus capture that assumption as a vertical line. The intersection of the money demand and money supply curves determines the interest rate.

This is faithful to Keynes departure from the Classics who considered the interest rate to mediate saving and investment (that is, a real variable). Keynes noted that the nominal interest rate was a monetary variable determined by the demand for liquity and the supply of money available.

Figure 16.1 Money Market Equilibrium

If the national income level was Y0 then the intersection of the relevant liquidity preference function and the money supply line would generate an interest rate of i0 – Point A.

What would happen if income rose to Y1?

At the current interest rate i0 there would now be an excess demand for liquidity (measured by the segment AB) and this would lead to the interest rate rising until the excess demand was eliminated at C (i1) given that the money supply would be fixed.

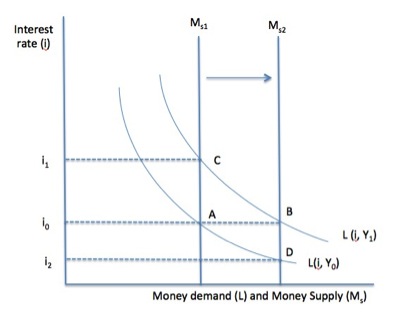

What would happen if the central bank increased the money supply?

If the national income level was Y0 then the intersection of the relevant liquidity preference function and the money supply line would generate an interest rate of i0 – Point A.

What would happen if income rose to Y1?

At the current interest rate i0 there would now be an excess demand for liquidity (measured by the segment AB) and this would lead to the interest rate rising until the excess demand was eliminated at C (i1) given that the money supply would be fixed.

What would happen if the central bank increased the money supply?

Figure 16.2 shows the impact of an increase in the money supply from Ms1 to Ms1.

At national income level Y0 and Ms1, the interest rate is i0 and the money market is in equilibrium at Point A.

If the money supply rises to Ms2 then there is an excess supply of money at i0 (measured by the segment AB) and the interest rate would drop until is reached i2 – Point D, where the demand for money is again equal to the money supply.

You can also see that if we start at Point A and the national income level rose to Y1 the interest rate could be held constant at i0 if the central bank accommodates the increased demand for money at the higher income level by increasing the money supply to Ms2.

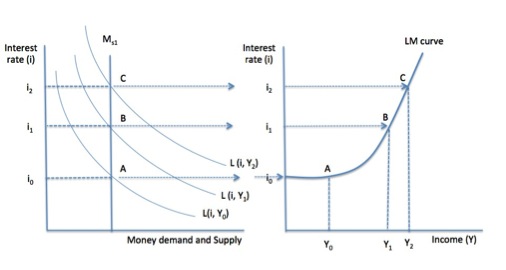

We are now in a position to derive the LM curve which shows all combinations of income and interest rates that are consistent with money market equilibrium.

Figure 16.3 shows the derivation of the LM curve. From the money market diagram, the Points A, B and C represent equilibirium states where money demand equals money supply for different levels of income.

Each equilibrium point is thus a unique combination of income and interest rates.

We can translate this understanding to a new graph (right-hand panel) where national income (Y) is on the horizontal axis and the interest rate (i) is on the vertical axis.

If we trace the respective equilibrium points across into the income-interest space diagram we get a series of points that are consistent with money market equilibrium.

The intersection of all those points is the LM curve.

|

Advanced material: John Hicks on his IS-LM Framework

John Richard Hicks – was a British economist who “invented” the IS-LM general equilibrium macroeconomic framework. In his 1937 article published in Econometrica – Mr. Keynes and the “Classics”; A Suggested Interpretation – Hicks sought to provide an interpretation of Keynes’ General Theory within a single diagram – the IS-LL model. As the model became popularised and standard macroeconomic textbook fare, the terminology became IS-LM to describe the product market equilibrium (IS) and the money market equilibrium (LM). The IS-LM model was designed to demonstrate how the determination of total real output was dependent on the interdependent outcomes in the product and money markets. Hicks said he “invented a little apparatus” (the IS-LM framework) to bring together Keynesian and Classical economics into an integrated model. By the 1970s, Hicks started to sign his academic papers John Hicks rather than J.R. Hicks, which reflected his growing sense of rejection of his earlier work. In 1975, to formalise is transition away from his earlier views, he wrote (Page 365):

The issue was that he began to realise that the static equilibrium IS-LM model left out the key contribution of Keynes – the importance of time and endemic uncertainty. For example, in the IS-LM model the current flow of investment is meant to be sensitive to interest rate changes in the same period, which is one way in which the money market outcome influences the product market equilibrium. But investment in any period is largely pre-determined by decisions made in previous periods. In 1980, Hicks wrote that he rejected the way in which is little aparatus had been deployed by economists and the policy interpretations they had drawn from it. He said (1980: 139):

By way of conclusion, he wrote (1980: 152-153):

The last point was telling. While the intersection of given IS and LM curves might reflect conditions now, the other points on the respective curves are what John Hicks called “theoretical constructions” (1980: 149) and “surely do not represent, make no claim to represent, what actually happened”. References: Hicks, J.R. (1937) ‘Mr. Keynes and the “Classics”; A Suggested Interpretation’, Econometrica, 5(2), April, 147-159. JSTOR link Hicks, John (1975) ‘Revival of Political Economy: The Old and the New’, The Economic Record, The Economic Society of Australia, 51(135), September, 365-67. Hicks, John (1980)'”IS-LM”: An Explanation’, Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 3(2): 139-154. JSTOR link |

Conclusion

PART 2 next week – manipulation of the LM curve and the derivation of the IS curve.

Saturday Quiz

The Saturday Quiz will be back again tomorrow. It will be of an appropriate order of difficulty (-:

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Site looks good Bill.

Can’t wait for publication.

Andy

ps Get a better picture of Randy on there.

What would happen if the central bank increased the money supply?

Bill, I think you’ve duplicated this line, one in the wrong place.

Great text and very clear explanation of the derivation of the LM curve from the speculative demand for money function. Way better than what one can find in most mainstream textbooks..

I hope next week you will not forget to elaborate on why “The LM curve should be non-linear and very flat at low levels of income and interest rates”.

Thanks.

I would like to buy this textbook when it comes out, even though I am layperson in these matters and not planning to become an economics student. I wonder where it will be available when published? I live near Brisbane.

Just published an endogenous money post keynesian alternative to IS-LM here

http://andrewlainton.wordpress.com/2013/07/26/a-simple-post-keynesian-alternative-to-is-lm/

In terms of the supply of lending power by banks (including central banks) and demand for leverage of income (borrowing) it is capable of demonstrating a number of phenomenon the Krugman version of IS_LM cannot including credit deadlock and japan style investment stagnation after completion of a phase of deleveraging.

I’ve been teaching that stuff a lot lately. Let’s see…

“The IS and LM curves are the equilibrium relationships pertaining, respectively, to the product (goods) market (investment = saving) and the money market (demand for money (liquidity preference) equals money supply).”

By implication, the bond market is in equilibrium as well. Since savings are invested into money and bonds, it is somewhere in the background, but you need it for the liquidity trap story.

“In an analytical sense, there were two unknowns – output and the interest rate – and two equations to allow us to solve the unknowns.”

I think that IS/LM is overdetermined. Where I=S you also find that supply=demand (and vice versa), which means one of the conditions is superfluous.

“We assume that the price level is constant. The IS-LM model allows us to introduce price level changes but at present we are operating in real terms.”

Are you referring to AD/AS here? If you really are operating in real terms you might think about pointing out that in the IS/LM the central bank is able to push the real interest rate around where in reality it only controls the nominal interest rate but not the price level.

“Money market equilibrium requires that the demand for money equal the supply. We use the term money demand to refer to the willingness to hold cash balances as part of a wealth portfolio.”

This is where the stock-flow confusion usually starts. Is it flows or stocks you are talking about? If money demand is a flow, then you should write “savings” instead of “wealth portfolio”.

“The demand for money – or as Keynes called it – the liquidity preference – is a function of the level of income and the interest rate.”

That the demand for money depends on the interest rate clashes with the General Theory (ch. 13) where Keynes writes: “If this explanation is correct, the quantity of money is the other factor, which, in conjunction with liquidity-preference, determines the actual rate of interest in given circumstances.”

“Precautionary motive – at times major events occur that need to be resolved through transactions – for example, maintaining a cash balance to pay for engine repairs on a car. This motive also tends to vary with national income as the higher is the level of economic activity, the higher are the overall transactions.”

It is often described to also depend on the interest rate. It is then omitted because speculative and transaction motive together more or less include the precautionary motive.

“At higher interest rates, more people will form the view that rates will fall rather than rise and the liquidity preference will be lower.”

What is probably even more important: at low interest rates, more people will form the view that rates can only rise and the liquidity preference will be higher.

“What would happen if income rose to Y1?

At the current interest rate i0 there would now be an excess demand for liquidity (measured by the segment AB) and this would lead to the interest rate rising until the excess demand was eliminated at C (i1) given that the money supply would be fixed.”

You have that paragraph twice in your text.

best,

Dirk

Well-done. I’m a student of BBA , and doing my second major in Economics at East West University, Bangladesh. This article helped me in preparing for my mid exam in ECO 302 Course. Thanks.