It was only a matter of time I suppose but the IMF is now focusing…

IMF still away with the pixies

The abysmal performance of the IMF in recent years has been one of the side stories of the Global Financial Crisis. They have consistently hectored nations about cutting deficits using models that were subsequently shown to be deeply flawed. They bullied nations into austerity with estimates of multipliers that showed that austerity would yield growth when subsequent analysis reveals their estimates were wrong and should have shown what we all knew anyway – that austerity kills growth. Their predictions have been consistently and systematically wrong – always understating (by significant proportions) any losses that would accompany austerity and overstating the growth gains. At times, in the face of incontrovertible evidence they have admitted their failures. But a leopard can’t change its spots. The IMF is infested with the myths of neo-liberalism and only a total change in remit and clearing out of staff could overcome that inner bias. Their latest offering – Japan: Concrete Fiscal, Growth Measures Can Help Exit Deflation – is another unbelievable reversion to form.

The full IMF (August 2013) – Japan 2013 Article IV Consultation – is the product of their (mostly) annual visit to all member countries – in this instance, Japan.

The IMF note that “(t)he Japanese authorities have embarked on an ambitious agenda to raise growth and exit deflation” which are “buoying the near-term outlook”.

One the one hand, they acknowledge that “(u)unprecedented monetary easing supported by fiscal stimulus is leading to a pickup in domestic demand with GDP growth” but then claim that fiscal and structural reforms are needed because there are “underlying risks” without them.

Decoded?

We learn that:

a credible medium-term fiscal plan should be adopted as quickly as possible as fiscal risks have risen further …

Which means?

Raising the consumption tax rate to 10 percent, while maintaining a uniform rate by 2015 is an essential first step, but the government also needs to formulate a concrete set of growth-friendly revenue and expenditure measures for implementation in the medium term to achieve a declining debt-to-GDP ratio.

There it is again – “growth-friendly” hacking into the deficit under the well-worn but totally fallacious IMF principle that you can get growth in spending by cutting spending.

Their growth estimates assume a dramatic private investment boom being supported by strong private consumption at a time that the contribution of government to real GDP growth goes from very solid in 2013 to sharply negative in 2014 and never positive against over the forecast horizon to 2018.

This is the stuff of fairies and pixies.

This mirage is to be accompanied by hacking into the labour market – they call it “reducing Japan’s excessive labour market duality” – which means undermine the working conditions of workers and reduce their pay. The latter undermines consumption capacity, which of-course undermines the growth potential of the economy.

The other part of mythology is that monetary policy will do all the hard lifting (growth stimulus) at a time that fiscal policy is being severely retrenched. We have seen during the five years of the current crisis that nations have cut rates to zero and built reserves until the cows come home(in the name of quantitative easing) with little impact.

Conclusion? A leopard can’t change its spots!

Section C of the Article IV Consultation Report is all about “Risks and Spillovers”.

They acknowledge that fiscal austerity and rising interest rates in other nations could slow Japan’s export growth but then claim that the dominate risks are domestic.

The major risk identified is that the Government doesn’t cut net spending and that the private sector forms the view that the deficits will undermine growth.

The IMF gobbledegook goes like this:

Without concrete measures, the new macroeconomic framework lacks credibility and may fail to raise growth and inflation expectations. Monetary policy might become overburdened and the rest of the world could be negatively affected through a weaker yen … Given high debt, a self fulfilling sell-off of JGBs due to the lack of a convincing debt- reduction strategy remains a possibility and markets could shift their perception of BoJ bond purchases toward debt monetization. Yields could spike, undermining domestic and global financial stability, increasing the risk of a reversal in emerging market capital flows, and putting pressure on the BoJ to maintain an accommodative stance for longer, possibly at the cost of its credibility and ability to efficiently manage inflation.

Oh my! It is a pity that this sort of nonsense has been wheeled out relentlessly for two decades with each prediction falling into the rubbish bin of unfulfilled predictions. Otherwise, we might have believed them this time! Not!

Apparently, “fiscal risks have risen in the past year” but “(u)nderlying upward pressure on interest rates from deteriorating fiscal conditions is assessed to be substantial, however, albeit masked by BoJ purchases and growing demand for liquid assets due to aging”.

Which translates into there is no risk other than in the inapplicable textbooks the IMF read and the idiotic models they spend their days tinkering with, which are based on these inapplicable textbooks and research papers.

There is – NO FISCAL PROBLEM. But the IMF thinks it is urgent. They produce a Box 3 to address the issue – “Are Fiscal Concerns Overblown?” Good, a head-on confrontation with the enemy (types like me).

We are referred to Chapter 1 of a supplementary research paper – Japan: Selected Issues – which analyses the “Determinants of Long-Term Interest Rates in Japan and Implications under the Government’s New Policies”.

Among factors identified which might explain why Japan has had “low and stable JGB yields” for the past two decades are this gem:

The public debt to GDP ratio has increased markedly for the last two decades … The deteriorating fiscal conditions are likely to exert an upward pressure on long-term rates, although this could be mitigated by expectations of drastic fiscal reforms to restore fiscal sustainability well before the public debt exceeds the private sector financial assets.

Think about what that sort of claim means for the formation of expectations relative to the assumptions underlying much of the IMF’s modelling that expectations are formed rationally.

For two decades, apparently, people (who buy bonds) have been willing to buy them at low and stable yields because any day now the Japanese government is about to unleash a “drastic” fiscal contraction which will “restore fiscal sustainability”. Who wrote that sort of stuff?

It is unimaginable garbage.

The narrative is couched as always in liberal dosages of “may” and “could” (in relation to the claimed fiscal crisis and impending insolvency). These are words that are never realised. The IMF uses them to hedge but leaves no doubt that they mean that the crisis is real and will (not “may”) happen.

Anyway, the substantive content of this Chapter is a panel econometric study of the determinants of long-term interest rates. The panel includes nations with currency sovereignty and those without and the sample includes nations that used to have sovereignty and then surrendered it.

An inspection of the structure of the estimating equation tells me that no allowance was made for that mismatch.

Even the qualifications noted fail to take into account the identified factors that allow Japan to keep interest rates low.

It was interesting that in the same week that the IMF released their latest commentary on Japan, the Financial Times published an article (August 1, 2013) – Japan has not learnt the lessons of its lost decade – by a Tokyo-based economist (working in a private research firm), one Peter Tasker.

If you don’t like the FT paywall (or don’t know how to get around it), you can read the same article for free here – Hegel on Abenomics.

He starts with this:

It’s after midnight and I’m sitting in a Roppongi bar discussing the subject with a knowledgeable Japanese bureaucrat.

“It’s essential to raise taxes,” he says, cradling a well-aged Islay malt. “If we don’t, investors will lose confidence and our bond market will collapse.”

“Aren’t you risking a serious recession?”

“A temporary blip, maybe. But the strengthening of public finances will be good for future growth.”

The reader is then told – “The year was 1997”.

The point he makes is that despite fiscal policy expansion maintaining a steady return to growths after its massive property collapse in the early 1990s and “Japan’s own banking system was on the brink of collapse” the “Japanese bureaucrats had convinced the prime minister of the day … that raising taxes on consumers was a national priority”.

The dialogue at that time if you want to check back through IMF papers was virtually identical to now.

For example, check out the – IMF Survey – published on February 10, 1997. There is a section, starting Page 47 entitled “Dealing with Japan’s Fiscal Challenges”.

There we read the familiar narrative:

Japan’s long-term fiscal viability has been undermined by rising budget deficits and future spending pressures associated with an aging population … Fiscal adjustment is critical … [massive cuts to health care and public expenditure and] … Increasing Japan’s consumption tax rate beyond the existing 5 percent … Such ambitious front-loaded adjustment measures … would avoid the necessity of introducing more aggressive measures later and would minimize the risk of undermining investor confidence during the adjustment period.

One could easily form the view that the IMF has a team of word processing officers who just spend their years cutting out of past reports and pasting them into the latest.

Something like the facility that this little site I constructed offers – The IMF-Compliant (BS) Report Generator – is probably the way they operate!

I discussed the 1997 folly in this blog – The last eruption of Mount Fuji was 305 years ago.

I noted (and explained) that there is never a situation where the bond markets can destroy a nation which has currency sovereignty. Never means NEVER.

The substantive issue in Japan’s case is that they are once again relying on Quantitative Easing to maintain growth and discussing the simultaneous introduction of fiscal austerity.

The problem is that QE will have no significant effect on growth. Please read my blog – Quantitative easing 101 – for more discussion on this point.

Any fiscal contraction will just take the nation back to 1997, where these same debates were rehearsed then and led to tax hikes – and – a dive back into recession.

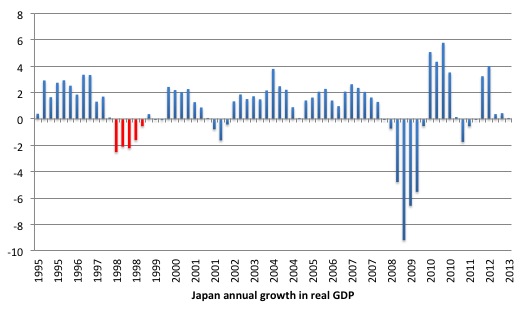

The following graph shows the annual rate of real growth in Japan from the March-quarter 1995 (at the onset of the asset price crash) through to the March-quarter 2013.

The property crash in th early 1990s caused a severe contraction in household consumption and private investment spending which culminated in a brief real contraction in 1994. Once the stimulus from the expanding budget deficit began to work real GDP growth regained momemtum.

By 1996, the same calls for austerity (fears about public debt ratio etc) that dominate the policy debate today were rampant in Japan and the government eventually bowed to political pressure and raised taxes in an attempt to reign in the budget deficit.

The public contraction on top of very fragile private sector spending – akin to the situation that most nations face today – caused a massive contraction in 1997 and 1998 – which increased the budget deficit (via the automatic stabilisers) and added to the public debt ratio (given both debt was rising and GDP was falling).

Peter Tasker notes that after the Japanese government bowed to the pressure and increased consumption taxes in 1997, real GDP growth collapsed:

In the event they drove the Japanese economy off a ten trillion yen fiscal cliff. If you tax something you are likely to end up with less of it. So it was with Japanese consumption. In a matter of months outright deflation had reared its ugly head. Retail sales fell into a protracted slump from which they have yet to emerge.

Soon afterwards Hashimoto was forced from office, his reputation for competence in tatters. The story goes that he bitterly regretted following the advice of his bureaucrats right until his untimely death in 2006.

After that collapse, the ratings agency, Moody’s then started to play games by downgrading the sovereign debt. Fortunately, the Japanese government did not take any notice, and, realising the mistake of 1996-1997, expanded their net spending again. The renewed fiscal stimulus saw real GDP grow very strongly in the ensuing years despite the rating agencies decision.

The Japanese government never had any trouble finding buyers for the debt it was issuing, they held complete control over interest rates, inflation fell, unemployment remained relatively stable and real GDP growth was strong through the period of the downgrade.

The decision by Moody’s was rendered irrelevant by the Japanese government who just exercised the power they had as a sovereign issuer of the currency.

You might wonder what happened in 2002? The recession that occurred then in Japan was largely driven by an export collapse (remember the US went into recession during this period) and a tightening of net public spending. This then provoked a fall in private investment spending and a rising saving rate. It had nothing to do with the ratings decision.

Once exports recovered and public spending support resumed the economy then grew relatively strongly despite the lower sovereign debt ratings.

And then the 2007 crisis arrived.

Any attempt to engage in fiscal austerity now will take them back into recession.

Peter Tasker also makes another important point:

The tax rise failed even in its own terms. Central government tax revenues fell more than 20 per cent over the subsequent 15 years and Japan’s debt-to-GDP ratio – a mere 40 per cent at the time – snowballed to more than 150 per cent.

Which is what the Eurozone if finding. Which is what the Australian government is finding. Which is what anyone who knows anything would tell you will happen. The automatic stabilisers are very powerful and typically will defeat these misguided attempts at cutting deficits in times of weak private spending.

Peter Tasker also notes that in the renewed fiscal expansion in 1998 and beyond, “Japan’s bond market, far from collapsing, embarked on an astonishing bull run that took 10-year yields to below 0.8 per cent”.

But the IMF thinks that is because everyone who was buying bonds at the near zero yields was doing so on the basis of an expected massive fiscal contraction which would mean the government could afford to pay them back. Drivel like that.

The problem noted by Peter Tasker is that “Japan’s populist press loves to hyperventilate about the country “going bust”, as do some respectable business magazines” and this puts pressure on the politicians to introduce damaging policy changes (such as pro-cyclical fiscal policy).

Conclusion

The conclusion:

Nobody knows the exact formula for leading an economy out of 15 years of deflation, but the probability of success is almost certainly higher if monetary and fiscal policy pull together, rather than in opposite directions.

Exactly.

And one hopes the IMF is ignored by the Japanese policy makers.

The lesson for today: as each habitual offering comes out from these Japanese economists and their mates in the press the best thing to do is to ignore it.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

I’m fairly sure Milton Friedman advocated a cure for Japan’s deflation which was about as ridiculous as the IMF’s. Friedman was obsessed by the money supply, as we all know. And I’m fairly sure he claimed that if the Japs printed money and bought back their debt, that would do wonders for the Jap economy (i.e. he advocated QE). His reason being that the money supply would rise.

The flaw in Friedman’s idea (as will be obvious to any MMTer) is of course that given the low yield on Jap public debt, there is little difference between monetary base and public debt. So the debt for money swap has little effect.

Can anyone confirm that Friedman said that, and if so where?

Bill,

I hear that Brazil as a now nett contributor to the IMF is unhappy with the EZ bailouts perhaps that is why European control of the top post was maintained with indecent haste?

Maybe the new growth economies BRIC as paymasters can control or at least negate IMF,s role in the future with a bit of luck!

Not sure the difference in yield between ‘bonds’ and ‘base’ is that relevant anyway.

As Bill notes in the QE 101 post:

.

Dear Bill

If government expenditure goes up, GDP will go up too, unless the additional expenditure consisted of transfer payments or was financed entirely by tax increases. That makes it hard to determine whether fiscal expansion was really successful. Suppose that Ruritania has 8 million people working in the private sector, 2 million in the public sector and 2 million unemployed. Now, the government hires 1.0 million jobless people to build infrastructure, without increasing any taxes. Obviously, the unemployment rate will go down and GDP will go up. However, if Ruritania already has adequate infrastructure, then this additional GDP will be useless, unless the other 1 million unemployed also start finding jobs.

My view is that a government should increase spending on items other than transfer payments only if the expenditure will produce goods or services for which there is a real need. There is no point in building an expensive road that will be used by 2 cars per hour. If there is no need for them, then fiscal expansion should consist of an increase in transfer payments or lower taxes or a combination of the two. Increasing transfer payments or lowering taxes also has the advantage that they require very little planning. For instance, cutting VAT by 50% takes only one legislative session.

My understanding is that a lot of Japan’s infrastructure built after 1990 is underutilized. Examples are railway stations and trains that are nearly empty all the time.

Regards. James

ChrisLongs says:

It would be a world changer if that was to occur, however, since the IMF is an extension of US foreign policy and exclusively serves the purpose of WS and the west, it will not happen.

Top Ten Reasons to Oppose the IMF

Where mortgage payments are tied to the base rate, then, the descretionary income of consumers will increase with a fall in the base rate?

Oops: discretionary.