During the recent inflationary episode, the RBA relentlessly pursued the argument that they had to…

The spurious distinction between the short- and long-run

There was an interesting article in the Wall Street Journal (July 7, 2013) by US economist Alan S. Blinder – The Economy Needs More Spending Now . I am building a little database of what well-known economists said in 2008, 2009 and 2010 at the height of the crisis and in the early days of the fiscal and monetary interventions and what they are saying now. There is a lot of dodging and weaving I can tell you. Stories change, previous prognostications of certainty now appear highly qualified and nuanced and facts are denied. Alan Blinder was worried that the US Federal Reserve rapid building of reserves would have to be withdrawn quickly because otherwise banks would eventually lend them all out and inflation would accelerate. Of-course, banks don’t lend their reserves to customers and the predictions were not remotely accurate. In the article noted, Blinder continues to operate at what I am sure he thinks is the more reasonable end of mainstream macroeconomics. He is advocating more spending as a means of boosting higher economic growth. But when you appreciate the framework he is operating in, you realise that he is just part of the problem and part of the narrative that allows the IMF to talk about “growth friendly austerity” – the misnomer (or outright lie) of 2012-13.

Alan Blinder is a professor at Princeton and a former central banker. I have always considered what he has written to be eminently more acceptable than some of the trash that comes out from say Chicago (Cochrane, Fama etc).

In the WSJ piece, he thinks that “a conceptual confusion that sounds pedantic but is highly consequential” in the current economic policy debate relates to:

… the failure to distinguish between the short-run and long-run effects of particular policies, which are often starkly different.

Mainstream theory has always considered such a distinction to be significant and the temporal separation into short-run periods and some distinct long-run period has been used to justify the case against policy-activism by government in the face of mass unemployment.

The extreme version of this separation is called the “classical dichotomy”. It is a highly technical literature and that makes it easy to follow if you are good at mathematical reasoning.

It is harder to explain it in words but here goes.

The short-run is a period where only the labour input is variable. So other inputs are considered to be fixed. The long-run is where all productive inputs are variable.

In the long-run, with free markets, full employment is the norm because all prices adjust to ensure that the optimal relationships hold.

The the classical dichotomy is explained in some detail in these blogs – Money neutrality – another ideological contrivance by the conservatives and Less income, less work, less income, more work!.

The short version is this:

1. Labour is employed at a real wage which equals its marginal contribution to production.

2. If the real wage is allowed to fluctuate it will ensure that there are enough jobs to satisfy those who want to work. All those who do not have a job then are voluntarily choosing not to work. So there is no involuntary unemployment.

3. All output produced at this level of employment is sold because prices and interest rates adjust to ensure that all leakages to spending equal the injections. That is there can never be a deficiency of effective (aggregate) demand.

4. If for example, people desire to consume less and save more interest rates fall (because of the excess funds available) and investment increases to match the rise in saving and aggregate spending does not fall – only the composition between current goods and future goods changes.

5. All the real variables in the economy – output, employment, real wage, and in the classical version, interest rates – are thus determined with no reference to any monetary variables. All this is explained within a simple barter economy.

6. Introducing money into the analysis changes none of 1-5. It is just a way of explaining the price level that sits on top of this real system. There is a dichotomy between explaining the determination of the real sector variables and explaining the monetary variables (price level, money wage level).

7. The Quantity Theory of Money (QTM) claims that the growth in the money stock determines the inflation rate. Of-course, this assumes that 1-5 maintain full employment (so that output is always determined and at the full capacity level) and tha the turnover rate of the money stock in fulfilling transactions is constant and predictable.

8. While some economists like to think this is a position that the economy is in at all times, the more reasonable mainstream economists recognise that there are short-run fluctuations that respond to variations in demand (principally investment). But even these characters claim that the long-run tendency of the economy is captured by the classical dichotomy.

This is not the blog to entertain all the criticisms of the concept. Please see the linked blogs above and also the blogs covering Keynes and Classics in our forthcoming textbook:

- Keynes and the Classics – Part 1

- Keynes and the Classics – Part 2

- Keynes and the Classics – Part 3

- Keynes and the Classics – Part 4

- Keynes and the Classics – Part 5

- Keynes and the Classics – Part 6

- Keynes and the Classics – Part 7

- Keynes and the Classics – Part 8

- Keynes and the Classics – Part 9

But Alan Blinder believes that we should still be in this dichotomised world and he thinks the “prominent recent example’ of failing to appreciate the difference between the short- and long-run periods:

… is the battle over reducing the federal budget deficit. Some say lower deficits are essential for economic growth; others say reducing the deficit will damage growth. Who’s right? Actually, they both are. It depends on the time frame.

Any Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) theorist will answer the question “who’s right?” differently. Reducing deficits both damages real growth and damages the growth path of the economy in certain situations and in other situations will have quite the opposite impact. It all depends, which is why hard and fast fiscal rules are usually totally inappropriate.

The differentiation between the short-run and the long-run by Alan Blinder, which is thoroughly mainstream, prompted me to think of the work of the late Polish economist Michał Kalecki, who apparently even Paul Krugman is now even advocating people take notice of.

In his New York Times column last week (August 8, 2013) – Phony Fear Factor – Paul Krugman noted that he had at some earlier point read Kalecki’s work and “thought it was over the top”. Why? “Kalecki was, after all, a declared Marxist (although I don’t see much of Marx in his writings)”.

I thought this admission was interesting. How many so-called academics out there don’t read something that might be important because of some label (Marxist?)? That level of dismissiveness is a worry in itself.

But then the second statement (not “much of Marx” etc) tells me that Paul Krugman better re-read the work of Kalecki a bit more closely. It is full of Marx!

But it is good that he is introducing one of the more insightful economists to his readership.

Regular readers will know that Kalecki is a favourite of mine and the traverse between Marx to Kalecki into modern analysis (and now to Modern Monetary Theory (MMT)) is much stronger for me than any side-stepping into Keynes and his General Theory.

Among the MMT crew though I stand somewhat alone in that regard I have to admit – they all have a much higher regard for the contribution of Keynes than I do.

Kalecki always considered that if we are to understand the behaviour of capitalist monetary economies with their particular ownership relations that determined how production was organised and distributed, then analysing the behaviour of effective demand is not only important for comprehending the cycles (Blinder’s short-run) but also the longer-term dynamics of the system.

Ignoring the effect of effective demand on the long-run is a mainstream proclivity but leaves the narrative largely devoid of meaning and import.

Here is a longish quote from Kalecki’s short 1970 paper (7 pages in total) – “Theories of Growth in Different Social Systems”, published in Scientia (pages 111-12 in the reprint – see below):

But, from the time the discussion of economic dynamics has concentrated on problems of growth the factor of effective demand was generally disregarded. Either it was simply assumed that in the long run the problem of effective demand does not matter because apart from the business cycle it need not be taken into consideration; or more specifically the problem the problem was approached in two alternative fashions: (i) The growth is at an equilibrium (Harrodian) rate, so that the increase in investment is just sufficient to generate effective demand matching the new productive capacities which the level of investment creates. (ii) Whatever the rate of growth the productive resources are fully utilized because of long-run price flexibility: prices are pushed in the long run in relation to wages up to the point where the real income of labour (and thus its consumption) is enough to cause the absorption of the full employment national product. I do not believe, however, in justifying the neglect of the problem of finding markets for the nation product at full utilization of resources with in fashion (i) or (ii). It is generally known that the tend represented by case (1) is unstable: any small fortuitous decline in the rate of growth involves a reduction in investment and in consequence of the national income, in relation to the stock of equipment, which affects investment adversely and induces a further fall in the rate of growth … Nor do I subscribe to the long-run price flexibility underlying the theories of type (ii). The monopolistic and semi-monopolistic factors involved in fixing prices – deeply rooted in the capitalist system of all times – cannot be characterized as temporary short-period price rigidities but affect the relation of prices and wages costs in both the course of the business cycle and in the long run. To my mind the problem of the long-run growth in laisser-faire capitalist economy should be approached in precisely the same fashion as that of the business cycle.

[Full Reference: Kalecki, M. (1970) ‘Theories of Growth in Different Social Systems’, Scientia, 5-6, 311-316

reprinted in Osiatynski, J. (ed) (1993) Collected Works of Michał Kalecki: Volume IV: Socialism, Economic Growth and Efficiency of Investment, Clarendon Press: Oxford, 109-117]

Any discussion of the long-run in Kalecki’s work, unlike the mainstream (Say’s law) conception, contains no notion that the long-run is a steady-state attractor (that is, a (natural) point that the macroeconomy gravitates to when imperfections are eliminated).

Kalecki’s notion of the long-run bore no insinuation of “equilibrium” (competitive equalisation of rates of profit; realised expectations; full employment).

In effect, while his position shifted (in nuances) throughout his life, Kalecki rejected the mainstream view that there was a state we might call the long-run, which was separable from the economic cycle.

Kalecki said:

In fact, the long run trend is but a slowly changing component of a chain of short run situations; it has no independent entity …

That is the long-run is just a sequence of short-runs. And that these short-runs are all linked by path-determinancy – so you are today where you have come from. Effective demand (with investment as a major variable component) drives output and employment, but, in turn, influences investment (through expectations and profit realisation), which determines the path of potential output.

Investment today – by expanding productive capacity – requires a growth in effective demand tomorrow to absorb the output forthcoming from that extra productive capacity. This was a problem well understood by the likes of Roy Harrod and E.V. Domar (and Marx) – all who were largely ignored by the mainstream growth theory that underpins Alan Blinder’s short-run and long-run division.

In considering the long-run as a sequence of short-run situations he considered long-run influences to be manifest and developed within the short-run.

What are these long-run forces? Answer: factors that have an enduring influence on the path the economy takes. So these factors are evident by the sequence of short-run situations and so analytically it is impossible to decompose the long-run from the short-run.

He argued that factors such as the institutional characteristics of the nation, market concentration, technological change and the class struggle between workers and capital were such long-run factors.

Note the Marxian elements in his argument (apparently missed by Paul Krugman).

For example, Kalecki’s income distribution analysis was unique for his day because he eschewed the perfect competitive model as a starting point in analysing firm behaviour and price setting. He considered oligopoly (imperfect market competition) to be the norm (that is, concentrated markets where firms had price-setting power). He then wanted to know what determined the firm’s price setting power. In the mainstream, firms are initially cast as having no price-setting discretion as they are perfectly competitive.

Kalecki also began with the observation that full employment was an exception not the rule so firms typically had spare capacity and thus could expand output as demand increased at more or less constant unit costs. In the competitive model firms are always assumed to be oprating at full capacity and face increasing unit costs and so prices rise when demand rises. The real world fits the Kalecki starting point.

In considering the determinants of the “mark-up” that these empowered firms placed on their unit costs, Kalecki interwove his long-run factors with the short-run factors. It is a great example of the way in which he considered it impossible to really differentiate a separate analytical long-term temporal plane.

He said that the degree of industrial concentration (how many firms in a market etc) was inversely related to price-setting power. This is a “long-run” influence because changes in concentration move slowly.

However, the business cycle is interposed on these underlying factors and are considered “short-run” factors. So when the economy turns downwards, the capacity of firms to pass on price rises is strained and so the mark-up may be squeezed.

Further, while the class struggle underlies the determination of the output distribution, this is, in itself, mediated by the state of the business cycle – so when times a good, unions are stronger than when times are bad.

So you get a good picture of the way he eschewed the mainstream (neo-classical) long-run from these examples.

Some mainstream economists assert that while price rigidities can render the real economy susceptible to changes in the money supply (positive effect) in the long-run, when all these rigidities are eliminated the classical dichotomy asserts itself.

This, presumably is Blinder’s position.

Clearly, Kalecki didn’t agree with that. The concept of a separable “long-run” in highly dubious.

I particularly like this construction:

In sum, in neoclassical economics the “long run” cannot be a temporal concept. It does not refer to any real world process of evolution or change. Even notional processes are shown to be difficult to conceive. “Long run,” by definition, refers to a situation in which no mistakes are made and all the (theoretically expected) adjustments are achieved. It is not in time, it is not even a secular trend. It is just an aprioristic statement of what the world would look like should the theory be correct (emphasis in the original).

The source is Fernando Carvalho (1984-85) ‘Alternative Analyses of Short and Long Run in Post Keynesian Economics’, Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 7(2), 214-234. For those who have access to JSTOR the link is HERE.

However, why does Alan Blinder think it is important to maintain the temporal fiction between the short-run and the long-run?

He writes:

In the short run, deficit reduction slows growth by cutting the economy’s total spending. After all, to reduce its deficit, the government must spend less itself or tax people more. This year, the tax hikes and government spending cuts agreed to in January and before are probably reducing GDP growth by about 1.5-2 percentage points. Think about that. The U.S. economy is struggling to achieve 2% growth this year. Without the fiscal self-punishment, we might be humming along at closer to 4%.

I totally agree with this statement as would Marx, Kalecki, Keynes and many others.

Effective demand (total spending) occurs where firms are producing and selling at a level consistent with their current expectations of return. If that level is below the full employment level then demand has to rise to stimulate the expectations of higher returns and to induce firms to produce more output and to employ more people.

He then deals with the “long-run” claim:

Yet you hear every day that large budget deficits threaten growth. How can that be? The answer is that, in the long run, a larger accumulated public debt probably spells higher interest rates, which deter some private investment spending. Economies that invest less grow less.

So a combination of loanable funds theory leading to crowding out is invoked. It is clear that economies that invest less grow less over time.

I provided a detailed critique of the loanable funds doctrine in the blogs linked above. But while I am writing about Kalecki he provided some very pithy refutations of it.

In the article that Paul Krugman refers to – Political Aspects of Full Employment (published in 1943 in the Political Quarterly) – Kalecki wrote (Page 348):

It may be asked where the public will get the money to lend to the government if they do not curtail their investment and consumption. To understand this process it is best, I think, to imagine for a moment that the government pays its suppliers in government securities. The suppliers will, in general, not retain these securities but put them into circulation while buying other goods and services, and so on, until finally these securities will reach persons or firms which retain them as interest-yielding assets. In any period of time the total increase in government securities in the possession (transitory or final) of persons and firms will be equal to the goods and services sold to the government. Thus what the economy lends to the government are goods and services whose production is ‘financed’ by government securities. In reality the government pays for the services, not in securities, but in cash, but it simultaneously issues securities and so drains the cash off; and this is equivalent to the imaginary process described above.

As I have noted previously – the government just borrows what it has spend in the past. Kalecki said that a “budget deficit always finances itself”, which is a specific version of the notion that spending brings forth its own saving via income changes.

The loanable funds doctrine considered saving to be finite at any point in time and various users of these funds would compete against each other for access. The interest rate mediated this access and determined who got the funds. In this static environment it is easy to see why they would claim private investment lost out if government attracted the finite saving by offering debt instruments.

However, Keynes formally broke with this view by noting that saving is a function of national income (non-consumption). As income grows so does the pool of saving.

So spending, which Blinder acknowledges drives income growth, also produces the leakages (savings) from the expenditure stream that provide the room for investment spending, for example.

That was the important break from the classics and led to Keynes demolishing the classical dichotomy. But Kalecki also clearly developed these insights (in my view independently from Keynes) and knew that deficits did not have the “long-run” issues that Blinder is worried about.

Kalecki offered some great insights into why budget deficits do not cause investment to decline (1990, Page 360):

Is it not wrong, however, to assume that private investment will remain unimpaired when the budget deficit increases? Will not the rise in the budget deficit force up the rate of interest so much that investment will be reduced by just as much as the budget deficit is increased, thus offsetting the stimulating effect of government expenditure on employment? The answer is that the rate of interest may be maintained at a stable level however large the budget deficit, given proper banking policy.

This quote is from the 1944 paper Three Ways to Full Employment, which was subsequently reprinted in Osiatynski, J. (ed) (1990) Collected Works of Michal Kalecki: Volume I. Capitalism: Business Cycles and Full Employment, Clarendon Press: Oxford]

He detailed how central banks could ensure stable interest rates. He also understood that investment was determined by expected returns, themselves a function of the state of aggregate demand – the links between time periods are thus evident.

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) explains how loans are not constrained by reserves and banks will create deposits as they originate loans for any credit-worthy customer.

Taken together, this is why crowding out should be rejected as a viable explanation of what happens when budget deficits occur.

Finally, today (running out of time), Blinder expresses his short-run/long-run dichotomy in this way:

Long-run growth is supply-determined; it depends on an economy’s ability to produce more goods and services from one year to the next. To accomplish that, you need four basic ingredients: more labor, more capital, better technology, and-if you can manage it-a better-functioning economy that utilizes inputs more efficiently. These four ingredients constitute the essential core of supply-side economics, and deficit reduction helps boost growth via the second: more capital.

In the short run, however, output is demand-determined. The big question is how much of the economy’s productive capacity is used. And that depends on the strength of demand-the willingness of businesses, consumers, foreign customers and governments to buy what American businesses are able to produce. When demand falls short of supply, deficit reduction hampers economic growth by reducing demand even further.

But the development of that productive capacity ekes every day according to the state of demand. The long-run just tells us where all the short-runs have been.

Blinder thinks that his distinction would mean that the US should not “reduce the deficit too aggressively right now, while the economy is still weak and needs all the spending it can get.”

But he thinks that the US should:

Instead, enact laws today that will reduce the deficit substantially, but several years down the road, when the economy will presumably be stronger. Sensible as this prescription is, recent budget policy in the U.S. has been nearly the opposite. We have slashed the current budget deficit while doing next to nothing about our serious long-run fiscal imbalance. Not very smart.

So invoke a fiscal rule and delay its introduction.

Please read my blog – Fiscal rules going mad … – for more discussion on this point.

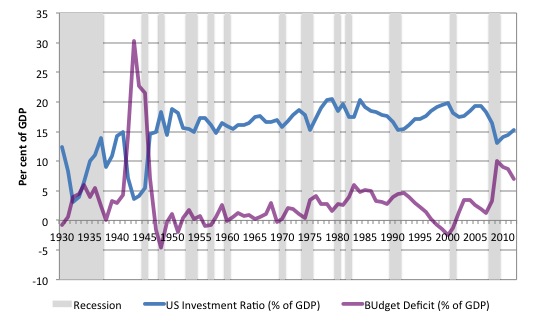

And just to dig a little into data, the following graph shows the US Investment ratio (Gross Private Investment as a percent of GDP) and the Federal Budget Deficit as a percent of GDP from 1930 to 2012. The annual GDP data is from the US Bureau of Economic Analysis and the Budget data is from the US Congressional Budget Office. The shaded vertical bars are the – NBER recession dates.

The recession dates are provided for quarters so I have taken some liberties in distributing the quarters across the annual observations. But the shade will at least occur in the year in which most of the particular cyclical event occurred.

The data shows as you would expect that the investment ratio plunges during recessions and the budget deficit rises courtesy of the automatic stabilisers, in the first instance, and then any discretionary fiscal stimulus on top of that.

It is difficult using formal econometric techniques to net out the causal relationship between the investment ratio and the budget deficit. There is not clear evidence that investment falls in any “long-run” period when budget deficits persist.

Clearly, the US government has run a budget deficit almost always during the period shown and the investment ratio has fluctuated between around 15-20 per cent in that period.

The higher investment ratio sub-periods were actually associated with higher than average budget deficits.

Conclusion

The deficit should be whatever is required in each period to ensure that effective demand is at a level that is consistent with achieving potential output – that is, full employment.

That might require a continuous sequence of deficits forever. Most likely given the historical behaviour of the external sector and private domestic sector’s in most nations.

That is enough for today!

I have a question on reserve operations.

I think I understand the MMT position

as again stated in this blog

banks cannot lend money out from reserves held at the central bank

there is no determistic ratio from reserves to broad money

loans build bank assets/ liabilities

but sometimes it is added that these assets can be used to meet

reserve requirements ” if necessary”

how does that work?

money transers from customers accounts to the banks’ reserves held at the central bank

presumably the same money cannot be in both the customers account

and at the central bank simultaneously ?

what is the mechanism by which loans once agreed by a bank and deposited in

customers accounts can end up meeting the banks reserve requirement with

the central bank?

Always impressed with quotes from Kalecki

whether its concerning income distribution or restrictive competitive practices

the myth of the “efficient capitalist long term “of classical and neo classical models laid bare

“The deficit should be whatever is required in each period to ensure that effective demand is at a level that is consistent with achieving potential output – that is, full employment.”

I think that is because of the effect of increased money entering the economy as a result of the deficit. The new money supply is increasing demand towards potential output. But that is just using the government to conduct monetary policy isn’t it? Shouldn’t the monetary arm of government be conducting monetary policy through more effective monetary distribution mechanism than what we already have in order to achieve the same goal but more efficiently?

Why do banks borrow overseas if there are no reserves requirement by their Central Bank? Is that a requirement of those Basel laws?

Kevin,

“there is no determistic ratio from reserves to broad money”. That statement isn’t quite right. I’d re-phrase it thus, “assuming the central bank decides to forgo control of interest rates, it can have considerable influence on commercial bank lending by imposing reserve requirements and then controlling those reserves”.

Central banks are monopoly suppliers of central bank money, and like all monopolists, they can control volume or price of loans, but not both.

But in the final analysis, or when push comes to shove, commercial banks just don’t need central banks at all: they can always use assets other than central bank money to settle up between themselves. In fact they already do the latter to a limited extent via inter-bank loans.

“loans build bank assets/ liabilities

but sometimes it is added that these assets can be used to meet

reserve requirements ” if necessary”

how does that work?”

There is nothing created by commercial bank lending that will serve as reserves, far as I know.

Bill,

This is a bit off topic. Re your criticisms of Cochrane (I assume that’s John Cochrane), he did have a good article in the Wall Street Journal recently. He made the point that if bank creditors who want their bank to lend on their money so as to earn interest all have to bear the loss if those loans go bad, then banks as such cannot suddenly fail, plus bank subsidies disappear, including the TBTF subsidy.

The authors of Dodd-Frank, Basel III, etc have churned out thousands of pages and regulations, but have failed to dispose of bank subsidies. Cochrane’s point is beautifully simple by comparison. See:

http://www.hoover.org/news/daily-report/150171

Dear Bill

Suppose that I have a nephew with irregular employment income. Whenever his employment income falls below a certain level, I supply him with cash to insure that his total income doesn’t fall below that level. That will work as long as his employment income remains totally independent of my cash contributions. That is highly unlikely. Because he knows that I will make up for any shortfall in his employment income, he can choose to change his working behavior so that his employment income will be lower than it would be if he couldn’t count on my financial assistance.

Similarly, if government deficits will always be used to compensate a fall in total private demand, what guarantee is there that total private demand will remain completely independent of deficits. In other words, isn’t it possible that aggregate demand becomes permanently dependent on government deficits?

Regards. James

Ralph

“they can always use assets other than central bank money to settle up between themselves. In fact they already do the latter to a limited extent via inter-bank loans”

Interbank loans means they lend reserves to each other as far as I’m aware.

Since I’m finding a lot of upcoming current mainstream economists that briefly engage with MMT say MMT doesn’t say anything different to what they’ve been saying for years (poppycock, if they do it is as clear as mud) but I think this bit from Blinder clears up some agreement I have seen from some known mainstream economists in recent times. The distinction they make is the short run which has been outlined above (consistent I think with MMT) and the long run (inconsistent with MMT).

My immediate thought is cognitive dissonance as common sense dictates long run is a series of short runs.

So in the short run we all tend to be in agreement – just see Krugman’s attempted engagements with MMT. We do more or less agree on policy recommendations currently but we disagree on what framework to use.

Bill,

I don’t think I quite understand your antipathy to Keynes’ General Theory and that it is a substantial side-step. I think we might both agree that the GT is 1) published in an unfinished state, 2) wrong in places, and 3) not well written as a whole. An example of 2) is Kalecki’s correction of Keynes’ theory of investment.

Kalecki thought it was close enough to the book he was himself thinking of writing that on receiving it, he was ill for three days, saying that Keynes had written what he was going to write. You and I might then further agree that their theories, while not identical, were possibly close enough to produce this strong emotional reaction in Kalecki, taking into account his personality, so different from that of Keynes’.

If we interpret Kalecki’s reaction to the GT as due to him thinking that Keynes’ and his theory exhibited considerable overlap and that this was reasonable, then I do not understand the basis for your antipathy to the GT.

On a different note, I would re-conceptualize Kalecki’s view of the relationship between the short run and the long run from a Fourier-like perspective, which would support Kalecki’s contention that the long run had no independent ontological status of its own. It would go thus: the long run is not a ‘component’ of a set of sequences of short runs but, rather, simply a consequence of them, analogous to the way that a Fourier analysis of a complex sound shows how it is made up of a number of overlapping simpler sounds. While the analogy isn’t exact, it does support his conclusion, which could be interpreted as supporting a view of the long run as a kind of artifact, dependent on other, more real shorter-run, processes.

Senexx,

While I really enjoyed your cognitive dissonance example, I don’t think by itself it will do the work you want, which is to bring us all to agreement “in the long run”. We might have to invoke other processes like those studied by Solomon Asch in his Minority of One. It might be a bit of a stretch, but could be worth the effort in the long run.

I always thought when an economist says the “long-run”‘ they mean “after I retire.”

You shouldn’t eat in the short run because in the long run you are fully fed, so eating in the short run will only make you overweight.

It is likely that you are familiar with Godwin’s Law, invoking Hitler, ends most online interaction. I believe there is a similar law regarding Marx. Both have been heroes of totalitarian regimes.

Bill,

Your short version of the classical dichotomy is a really handy summary for us laypeople. And it’s great to seem more quotes from Kalecki. I have added this blog to my favourites.

Kind Regards

lxdr1f7,

Good point. I didn’t explain what I meant at all clearly. What I was trying to say was that in the absence of a central bank which offers a settling up facility for commercial banks, the latter would find some other way of settling up. And one way of doing that would be to let inter bank debts remain for longer than is currently the norm. And only if some bank appeared to be permanently in debt to others would the latter demand something of real value from the former (e.g. property, shares or whatever).

So if there was no central bank, inter bank lending would help commercial banks do without reserves or the central bank settling up facility. But you’re right: under the EXISTING SYSTEM, commercial banks actually lend reserves to each other.

A bit complicated, and I fell arse over tit on that one.

Incidentally, the blogger Lord Keynes recently claimed that prior to the first world war, commercial banks actually did do some settling up with assets other than central bank money, but I haven’t checked his sources.

I understand that a bank’s reserves are held within the system, but I have read that a bank can hypothecate its reserves to another entity and then use the money that it gets from the hypothecation to spend as it wants – gamble in the stocks, bond and commodities markets. And, that is the reason that banks are so concerned about tapering. Is there any truth to that?

James Schipper

If you treat the overall economy the way you suggest in the example of your “nephew” it would just create inflation without any positive effect on real gdp. Inflating the money supply doesn’t mean that the recipients will always do less though it just depends on how money is administered into the system. I don’t think inflating the money supply will result in people doing progressively less but I don’t think it is the ideal way of supply the economy with money and also subject to cronyism and corruption.

James Schpper

“Similarly, if government deficits will always be used to compensate a fall in total private demand, what guarantee is there that total private demand will remain completely independent of deficits.”

Private demand is NEVER independant of the government’s budget deficit. A lack of aggregate demend is always and everywhere due to a lack of government net spending.

It is a pretence to believe that private sector spending or investment can sustain itself without the appropriate level net government spending.

Kind Regards

Charlesj

Why can the private sector not sustain itself without the appropriate level of net government spending?

Without government net spending, money in the economy is bank money, meaning that assets and liabilities net to zero and interest expense is a constant and growing demand leakage. Except for those economies with a net is a foreign account surplus. However, at the global level,this also nets to zero. This is therefore unsustainable.

Hence, supporting reduced government net spending is equivalent to supporting continual monetary crises, which I think is the playbook.

“Without government net spending, money in the economy is bank money, meaning that assets and liabilities net to zero and interest expense is a constant and growing demand leakage.”

Thats a problem because we allow banks to issue the inside money supply as debt. If bank deposits arent lent into creation then the private sector is in balance because the interest expense is interest income to another entity.

what is the mechanism by which loans once agreed by a bank and deposited in customers accounts can end up meeting the banks reserve requirement with the central bank?

They can’t, Kevin, if I understand the question correctly. There is no operation by which balances move from a depositor’s commercial bank account to that bank’s reserve account. A bank’s reserve account balance can only increase if (i) reserves move into it from another bank’s reserve account due to an interbank payment or interbank loan, (ii) the treasury makes a direct payment to that bank, or (iii) the bank engages in some transaction with the central bank that increases the balance. Such transactions include selling or repoing a security to the central bank, borrowing the reserves from the central bank, and being the recipient of an interest payment from the central bank.

lxdr1lf7

How did those depositors get the money to deposit in the first place? From firms, who got their money from whom, etc. If there is no government spending, then a bank has to loan it out.

thanks for your expertise

it was what I expected

but have seen the comment even from those who except that banks do not need

reserves to lend but have suggested if necessary reserves could be topped up from

loans

on the debate on reliance on government sector deficit for overall growth

has leakage from the increasing inequality of income ( the savings of the rich)

alongside the general increase in foreign sector deficits in the developed world

mean that historically large government sector deficits are required for full

voluntary employment .( for the foreseeable short term)

pebird

“How did those depositors get the money to deposit in the first place? From firms, who got their money from whom, etc. If there is no government spending, then a bank has to loan it out.”

Yes gov. money has to be issued by the gov, I understand. But the gov doesn’t need to issue the money supply as debt. If the money supply needs to be expanded it can be expanded and recognized as equity on the balance sheet of the issuer. Equity could be considered a liab that doesn’t have to be paid back and wont mislead conservative types to require balanced budgets. Therefore it is more accurate to consider gov money as equity than as a straight liab.

Bill –

How likely it is depends on here interest rates are set. Historically interest rates have been set high to force the private sector to net save so that governments can afford to run continuous deficits – but that is a very undesirable situation, as the benefits of low interest rates exceed the benefits of government deficits.