I have received several E-mails over the last few weeks that suggest that the economics…

Why did unemployment and inflation fall in the 1990s?

I am writing several formal academic papers at present with various presentations coming up as the target and so blogs in the near future might reflect that sort of mission. Today I present some results of some work I am doing with my co-author Joan Muysken, which stems in part from theoretical work we outlined in our 2008 book – Full Employment abandoned. The current work formalises the influence of unemployment duration and underemployment on the inflation process. Initially, we are focusing on Australia (for a December presentation) but the scope of the work will generalise to a broader OECD dataset. A motivation is that underemployment has became an increasingly significant component of labour underutilisation in many nations over the last two decades. In some nations, such as Australia, the rise in underemployment outstripped the fall in official unemployment in the period leading up to the financial crisis. Underemployment is now higher than unemployment in Australia. There is now excellent data available for underemployment from national statistical agencies, which makes it easier to examine its macroeconomic impacts.

After the major recession that beset many nations in the early 1990s, unemployment fell as growth gathered pace. At the same time, inflation also moderated and this led economists to increasingly question the practical utility of the mainstream concept of the natural rate of unemployment for policy purposes, quite apart from the conceptual disagreements.

This skepticism was reinforced because various agencies produced estimates of the natural rate of unemployment (now referred to in common parlance as the Non-Accelerating-Rate-of-Unemployment – or the NAIRU) that declined steadily throughout the 1990s as the unemployment rate fell.

As the unemployment rate went below an existing natural rate estimate (and inflation continued to fall) new estimates of the natural rate were produced, which showed it had fallen.

This led to the obvious conclusion that the concept had no predictive capacity in relation to the relationship between movements in the unemployment rate and the inflation rate.

The early concept of the NAIRU argued that there was a constant and cyclically-invariant rate of unemployment which acted as a constraint against aggregate demand expansion.

Once spending pushed the level of activity (that is, reduced the unemployment rate) beyond that fixed level, inflation would result.

This claim led to major deflationary exercises in policy (in the 1970s and 1980s) now more popularly known as austerity which only pushed the unemployment rate up further. The mainstream proponents of this policy argued that the increases were temporary although Milton Friedman at one point was forced to admit it might take 15 years for the economy to adjust.

Of-course, the adjustment was mythical given the problem was demand- rather than supply-sourced.

Formal econometric work at the time (including my own work – that formed the basis of my PhD thesis) tested the “constancy” hypothesis and found that no evidence could be found to support the existence of a NAIRU independent of the actual unemployment rate.

Faced with mounting criticism, the NAIRU theorists progressively moved to a position where time variation in the steady-state was allowed but this variation is seemingly not driven by the state of demand – the so-called TV-NAIRUs.

This was an ad hoc response to the evidence against the NAIRU concept and as usual anything went.

This intermediate phase has spawned a frenetic period of estimation using a range of technical methodologies. Like the original concept, the attempts to model the time variation were based on shaky theoretical grounds.

The theory that generated the NAIRU in the first place provides no guidance about its evolution. Presumably, the evolution of unspecified structural factors have played a role, if we are to be faithful to the original (flawed) idea.

In this theoretical void, mainstream econometricians assumed that a smooth evolution was plausible but these slowly evolving NAIRUs bear little relation to actual economic factors.

That is, no structural variables (that were implicated such as welfare payments, minimum wages, etc) were moving in any way that would justify the estimates of rising NAIRUs.

The rising estimated NAIRUs were used by the mainstream to justify their claims that even as the official unemployment rate rose from 2 per cent to 8 per cent in a matter of years, there was still no role for aggregate demand policy (that is, fiscal stimulus) because all the increase in unemployment was structural or voluntary.

It was sheer nonsense but such was the iron grip on the policy debate held by the mainstream that policy makers went along with it and economies operated well below the true potential. The revised NAIRUs had the effect of deliberately deflating what the true potential capacity was.

Most of the research output confidently asserted that the NAIRU had changed over time but very few authors dared to publish the confidence intervals around their point estimates.

There was one noted exception (mainstream econometricians Staiger, Stock and Watson in 1997) and their so-called “state-of-the-art” estimation of NAIRU models led them to conclude that:

… these estimates are imprecise; the tightest of the 95 percent confidence intervals for 1994 is 4.8 to 6.6 percentage points. If one acknowledges that additional uncertainty surrounds model selection and that no one model is necessarily ‘right’, the sampling uncertainty is prudently considered greater than suggest by the best-fitting of these models.

What they came up with (Page 39) was 95 percent confidence intervals of 2.9 percent to 8.3 percent. In other words, they were claiming that they were equally confident that the NAIRU was 2.9 per cent or 8.3 per cent.

This range of uncertainty about the location of the NAIRU is clearly too large to be at all useful. Say the unemployment rate was currently 6 per cent. Then at the lower confidence interval bound (2.9 per cent) this would allow for a major fiscal expansion without inflationary consequences (using the flawed NAIRU logic).

But if the NAIRU was actually at the upper confidence interval bound (8.3 per cent), then according to the same (flawed) logic such a fiscal expansion would be highly inflationary.

The econometricians were unable to discriminate between the two possibilities – they were equally confident that both were true.

Undaunted by these ridiculous results, the policy makers ignored the imprecision of the estimates and just focused on point estimates (that is, ignoring the confidence bands), which invariably supported their ideological preference against any government fiscal intervention.

A further problem is that the modern studies include a host of other variables, which can influence the inflation rate independently of the unemployment gap. In this case, the NAIRU hypothesis, if valid at all, loses policy relevance.

But, unfortunately, the losses from a deflationary strategy are higher under these conditions and this reinforces the points made earlier. If the monetary authority responds to shifts in the Phillips curve (the relationship between unemployment and inflation) independent of the unemployment rate with higher interest rates, the eventual losses from rising unemployment will be larger.

One might conjecture that the authorities should only react to endogenous factors (the unemployment gap). But then if it cannot measure that accurately and cannot decompose the different sources of inflation impulse, then this strategy will also fail. The safest strategy is to avoid the use of monetary policy in this way.

By the 1990s, the estimates of the NAIRU were starting to come down again. But new problems emerged. Nations in that growth period consistently observed their actual unemployment rates being below the estimated NAIRUs but also inflation was falling.

The NAIRU theory says that if the actual unemployment rate is above the NAIRU, inflation falls and vice versa.

These anomalies were easily explainable by those who rejected the entire NAIRU approach (for example, yours truly) but they were largely ignored by the mainstream – because like a lot of their predictive content, their theories were violated by the facts.

While there are various explanations that have been offered to rationalise the way the estimated natural rates of unemployment fell over the 1990s (for example, demographic changes in the labour market with youth falling in proportion), one plausible explanation is that there is no separate informational content in these estimates and they just reflect in some lagged fashion the dynamics of the unemployment rate – that is, the hysteresis hypothesis.

That is certainly the most plausible hypothesis that is consistently supported by the data. In other words, the NAIRU concept is a dud and is basically part of the ideological weaponry that the mainstream use to argue against national government use of fiscal expansion to reduce unemployment and pursue true full employment.

Please read my blog – The dreaded NAIRU is still about! – for more discussion on this point.

A revised way of thinking about the Phillips curve

The question then arises as to why the unemployment rate and the inflation rate both fell in many nations during the 1990s. What does this mean for the Phillips curve (the relationship between unemployment and inflation)?

To understand this more fully, economists like me started to focus on the concept of the excess supply of labour, which is a key variable constraining wage and price changes in the Phillips curve framework. Unemployment has typically been the preferred measure of excess supply in the labour market (or negative excess demand).

The standard Phillips curve approach predicts a statistically significant, negative coefficient on the official unemployment rate (a proxy for excess demand). That is, when the unemployment rate falls, the labour market is said to tighten and workers are more able to demand money wage increases, which are passed on by firms with price-setting power (via their mark-ups) in the form of accelerating prices.

The “quality” of the unemployment pool is also considered. It is argued that “quality” (in terms of the disciplining capacity of unemployment to restrain worker wage demands) is related to unemployment duration and at some point the long-term unemployed cease to exert any threat to those currently employed.

Consequently, they do not discipline the wage demands of those in work and do not influence inflation. The hidden unemployed are even more distant from the wage setting process. So we might expect that the short-term unemployment is a better excess demand proxy in the inflation adjustment function.

While the short-term unemployed may be proximate enough to the wage setting process to influence price movements, there is another significant and even more proximate source of surplus labour available to employees to condition wage bargaining – the underemployed.

The underemployed represent an untapped pool of potential working hours that can be clearly redistributed among a smaller pool of persons in a relatively costless fashion if employers wish.

It is thus reasonable to hypothesise that the underemployed pose a viable threat to those in full-time work who might be better placed to set the wage norms in the economy.

This argument is consistent with research in the institutionalist literature that shows that wage determination is dominated by insiders (the employed) who set up barriers to isolate themselves from the threat of unemployment. Phillips curve studies have found that within-firm excess demand for labour variables (like the rate of capacity utilisation or rate of overtime) to be more significant in disciplining the wage determination process than external excess demand proxies such as the unemployment rate.

It is plausible that while the short-term unemployed may still pose a more latent threat than the long-term unemployed, the underemployed are also likely to be considered an effective surplus labour pool. In that case we might expect downward pressure on price inflation to emerge from both sources of excess labour.

Looking at the Evidence

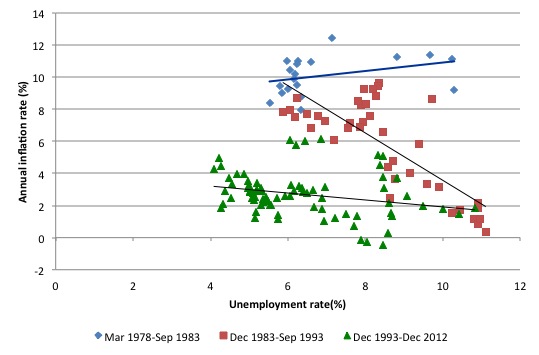

The first graph shows the relationship between the unemployment rate and inflation in Australia between 1978 and 2012. The sample is split into three sub-samples. The first from March 1978 to September 1983 is defined by the starting point of the most recent consistent Labour Force data (February 1978) and the peak unemployment rate from the 1982 recession (September 1983).

The second period December 1983 to September 1993 depicts the recovery phase in the 1980s and then the period to the unemployment peak that followed the 1991 recession. The final period goes from December 1993 to December 2012.

The solid lines are simple linear trend regressions.

The relationship between the annual inflation rate and the unemployment rate clearly shifted after the 1991 recession. The graph shows three particular points (September 1995, September 1996, and September 1997) as the Phillips curve was flattening and moving inwards. So over these years, the unemployment rate was stuck due to a lack of aggregate demand growth but the inflation rate was falling.

This has been explained, in part, by the fall in inflationary expectations. The 1991 recession was particularly severe and led to a sharp drop in the annual inflation rate and with it a decline in survey-based inflationary expectations.

The other major labour market development that arose during the 1991 recession was the sharp increase and then persistence of high underemployment as firms shed full-time jobs, and, as the recovery got underway, began to replace the full-time jobs that were shed with part-time opportunities.

Even though employment growth gathered pace in the late 1990s, a majority of those jobs in Australia were part-time. Further, the part-time jobs were increasingly of a casual nature.

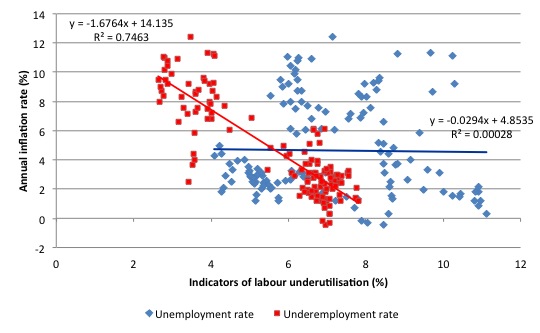

The next graph shows the relationship between unemployment and inflation from 1978 to 2012. It also shows the relationship between the underemployment estimates provided by the Australian Bureau of Statistics and annual inflation for the same period.

The equations shown are the simple regressions depicted graphically by the solid lines. The graph suggests the negative relationship between inflation and underemployment is stronger than the relationship between inflation and unemployment. More detailed econometric analysis (see later) confirms this to be the case.

The inclusion of underemployment in the Phillips curve specification helps explain why low rates of unemployment have not been inflationary in the period leading up to the Global Financial Crisis.

It suggests that shifts in the way the labour market operates – with more casualised work and underemployment – have been significant in explaining the impact of the labour market on wage inflation and general price level inflation.

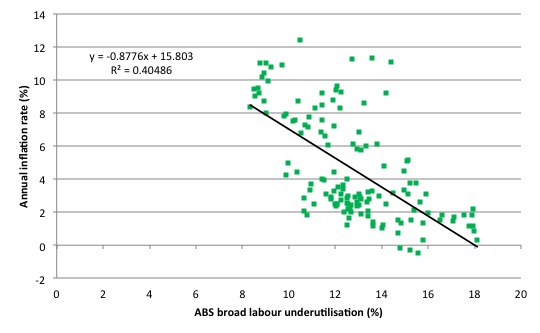

Finally, the next graph shows the relationship between annual inflation and the broad labour underutilistation rate (defined by the ABS as the sum of the unemployment rate and the underemployment rate) between 1978 and 2013.

There is now a very defined negative relationship between the two variables (which reinforces the notion that underemployment is now an important disciplining factor in the inflation process).

Econometric work

For those who are interested, the following results are based on more formal econometric estimation that I have been doing. I won’t have time to explain to those who are unfamiliar with this sort of modelling all the background concepts etc but I hope you will be able to read the text and glean its meaning.

In the formal paper there will be a section testing for the NAIRU dynamics. This is highly technical and I will spare you from that here. When the paper is ready for publication I will provide a link to the working paper form for those who are interested.

The results for the period 1978 to 2013 using quarterly data show there is no evidence of a constant NAIRU for Australia. The evidence supports the notion of a non-vertical long-run Phillips curve, which means that there is a trade-off between inflation and unemployment in both the short-run and the long-run (which are statistical concepts I will not explain here).

In other words, there is no evidence to refute the effectiveness of fiscal policy in reducing the unemployment rate down to very low levels. Some inflation is predicted but the trade-offs estimates are very flat (meaning that the resulting inflation increase as a result of such a stimulus is very small and finite.

From the discussion above two major hypotheses can be formed:

- That the short-term unemployment rate (STUR) constrains the annual inflation rate more than the overall unemployment rate (UR)? By implication we expect the long-term unemployment rate (LTUR) to be a statistically insignificant influence on the annual inflation rate.

- That the rate of underemployment (UE) exerts a separate negative impact on the inflation process.

The first of these hypotheses might require further elaboration.

The argument that wage determination is dominated by ‘insiders’ (the employed) who set up barriers to isolate themselves from the threat of unemployment is echoed in earlier Australian work that found ‘within-firm’ excess demand variables (like the rate of capacity utilisation or rate of overtime) to be more significant in disciplining the wage determination process (see Watts and Mitchell, 1990).

I published an article in 1990 with Martin Watts about this – see Abstract.

It is plausible that while the short-term unemployed may still pose a more latent threat than the long-term unemployed, the underemployed are also likely to be considered an effective surplus labour pool. In that case we might expect downward pressure on price inflation to emerge from both sources of excess labour.

This raises an interesting parallel to another aspect of the hysteresis hypothesis. In my earlier work (which is consistent with other international studies) I have found that structural imbalances that rise during a downturn are reversible. That is, a demand expansion reduces the estimated NAIRU because firms, when faced with a pool of workers who have lost skills in the downturn (as old capital equipment is scrapped etc) prefer to offer jobs with embedded on-the-job training than leave the jobs unfilled.

Thus, in a high pressure economy (one that is growing), firms lower hiring standards and address the skill deficiencies of the long-term unemployment by offering on-the-job training. Joan Muysken and I have shown before that employers access both the short-term and long-term unemployed pools in an expansion but that the long-term unemployed do not exert much influence on the inflation process.

How can those two observations be rationalised?

We argued that the labour market is structured in a way that increasingly, low-skill, low-pay fractional (part-time) jobs are being created which overcome the re-employment barriers facing the long-term unemployed. These secondary labour market jobs allow the long-term unemployed to enjoy upward mobility (limited) in an expansion.

The ‘primary’ and ‘secondary’ jobs are functionally related (the secondary jobs allow firms to make adjustments to demand fluctuations, for example, without disturbing the employment structure of the primary labour market.

Thus when employment growth is strong enough both pools of unemployed (short- and long-run) find employment opportunities. So while the long-term unemployed do have employment opportunities in an expansion they are in jobs that do not set the wage norms for the economy.

It is the wage norms that condition the overall rate of growth of money wages and also the flow-on from wage inflation to price inflation. The normal measure of inflation (some derivation of the Consumer Price Index) reflects price inflation.

However, once the long-term unemployed become re-attached to the employed labour force, they may influence wage setting via underemployment, given that they will often only have part-time jobs available to them.

As part-timers with some in-house training they become an entirely different proposition than when they were facing skill atrophy and motivation loss after more than 12 months without work.

While all the formal results will appear in the final paper, here is a glimpse.

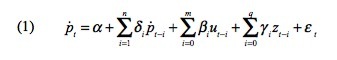

The following general autoregressive-distributed lag Phillips curve representation was used in the first stage of the work:

Here pdot is the annual rate of inflation, u is the unemployment rate, z is a vector of other cost shock variables (like import price inflation, capital costs), and the ε is a white-noise error term.

The dynamic equation (the big sigma signs indicate that n lags are available for estimation) also assumes that all the excess demand variables that we consider are stationary. I won’t explain that here because it would take a whole blog and most would still not get it.

Basically, it just means that the equation can be estimated in its current form. Later we have what are called error correction forms of the model but that is not for today.

The various excess demand proxies that we try (in order to advance the testing of the above hypotheses) are:

1. The official unemployment rate (UR).

2. The short-term unemployment rate (STUR) defined by ABS as those unemployment for less 52 weeks as a percentage of the total labour force.

3. The rate of the underemployment (UE).

4. The difference between the levels and the filtered trend derived using a Hodrick-Prescott filter of each of the unemployment rate variables. The variables created are UR Gap and STUR Gap. This construct is now commonly used and has been referred to in papers by the OECD and others as a test of the TV-NAIRU hypothesis.

The point here is that the concept of “excess demand” (or the related excess supply) is conceptual only and is not observed. The ABS does not publish a figure for “Excess Demand”.

So we have to proxy the concept with actual data available from the ABS. The four types of variables noted above are such proxies and we then have to combine theory (as above) with the statistical results to ascertain which is the “best” measure of the concept.

There is then a lot of technical discussion about so-called cointegration, unit root tests, and testing-down methodologies which I will leave out. You can read it in the final paper when it is completed if you care for that sort of thing.

Basically, it means that we start with a very general specification with lots of lags (because we are unsure whether, for example, unemployment exerts an immediate impact on inflation or whether, say, last quarter’s unemployment or even the quarter before that, is important).

Economic theory tells us which variables might be influential but the dynamic representation of that theory (that is, the actual statistical relationships) is derived from econometric modelling and sequential “testing down” from a very general equation using different measures of the underutilisation variable with lots of lags (in other words, all possibilities for temporal influence are allowed).

Testing down just means we test hypotheses about which variables and lags have “explanatory power” using well-known hypothesis testing methods and we finally arrive at a simplified equation with only statistically significant variables (and their lags) being present.

We also force each step of the “testing down” process to face a battery of so-called diagnostic tests – which just ensure the estimated results confirm with the basic assumptions of regression analysis. This means that the underlying distributional properties that are necessary for valid hypothesis testing are present.

D4LP is the annual inflation rate and (D4LP(-1)) is the inflation rate last quarter (which captures inertia). The annual increase in import prices is D4LPM). A binary dummy variable, DGST (defined as 1 in 2000:3 and zero otherwise) was included to take into account the introduction of the Goods and Services Tax system in Australia in July 2000 which created an outlier in the series.

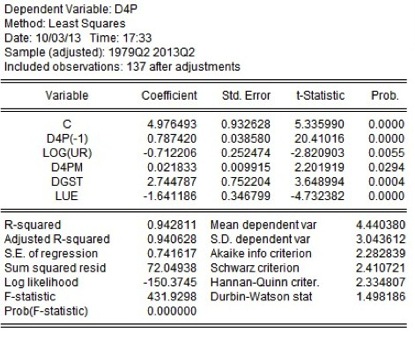

The first graphic is the results of one of the final (tested-down) estimated models that we arrived at. This one uses the unemployment rate (log(UR)) and the underemployment rate (LUE) as the excess demand variables.

The results show that both exert a statistically constraining influence on inflation with underemployment having a much stronger negative impact (larger negative coefficient).

So that is interesting in itself.

Import price inflation has the predicted positive effect. For those who know, the Wald test on the hypothesis that the coefficient on D4P(-1) which is a test of the constant NAIRU hypothesis failed (as did the same test for more general lag representations).

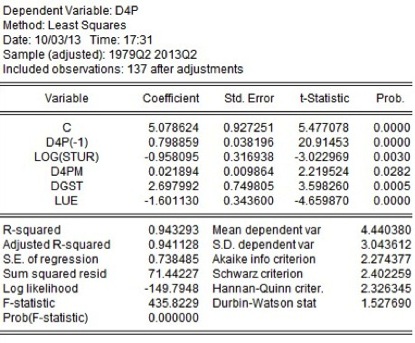

The next graphic shows what happens when we replace the official unemployment rate with the short-term unemployment rate (log(STUR)).

The results now suggest that:

1. Underemployment still plays a significant constraining influence on inflation independent of the which measure of unemployment is used.

2. The short-term unemployment rate is highly significant and provides a negative constraining impact on inflation. Importantly, its coefficient (measuring the degree of negative influence on inflation) is larger (in absolute value) than the coefficient on the aggregate unemployment rate (which of-course is the sum of the short- and long-term unemployment rates). This suggests that duration of unemployment does matter and the long-term unemployed have less influence on the inflation process as hypothesised.

The different values of the coefficients on the STUR and UR variables suggest the following dynamics are plausible. A downturn increases short-term unemployment sharply, which reduces inflation because the inflow into short-term unemployment is comprised of those currently employed and active in wage bargaining processes.

In a prolonged downturn, average duration of unemployment rises and the pressure exerted on the wage setting system by unemployment overall falls.

This requires higher levels of short-term unemployment being created to reach low inflation targets with the consequence of increasing proportions of long-term unemployment being created.

In addition, as real GDP growth moderates and falls, underemployment also increases placing further constraint on price inflation. The results taken together provide support for the hypotheses (1) to (2) outlined above.

Conclusion

I realise some of the technical details will evade some readers but the narrative should not. This sort of work helps to further undermine the NAIRU supremacy and also allows us to better understand why unemployment and inflation fell at the same time (even when the actual unemployment rate was falling well below the official estimates of the NAIRU (by central banks, organisations like the US Congressional Budget Office etc).

The NAIRU is meant to be an inflation constraint. The work shows that the NAIRU is a very slippery concept and of zero policy use. The reason that unemployment and inflation was falling together in the 1990s and later is because underemployment was rising.

Firms had devised a new way of creating labour slack, which allowed them to restrain the growth in wages and pursue higher margins.

More on this work another day.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Bill, you seem to have the regression equations and the variances reversed on the next to last graph. The blue diamonds show virtually no relationship at all between the variables.

There is a lot of scatter in the data, which is not unexceptional. Some of the data points look like outliers to me. What about an outlier analysis for some of the data?

Great article, thanks.

Bill,

I would like to see the intermediate step of showing how the different unemployment / underutilisation measures correlate to growth in wages. Then see how the other factors that affect prices change that further.

Kind Regards

This reveals the invisible ball and chain many people have felt holding them back these many years. What a terrible and unrecoverable loss of potential.

I will definitely keep this bookmarked. Brilliant!

Bill,

Very nice study. An R^2 of 0.94 is amazingly high for the ‘soft’ sciences.

I don’t understand your reasoning about the UR and STUR. Presumably STUR is only a component of the UR, so a higher coefficient could simply reflect the fact that the value of the factor entering the regression is smaller?

Also, a quick question, if I may. Why do you use ‘inflation rate last quarter’ if changes in unemployment are supposed to cause changes in inflation, and not the other way around? Where does the inertia come into it? If there were inertia in the inflation, you would have to look at future data points to see the coincidence of the series.

“The “quality” of the unemployment pool is also considered. It is argued that “quality” (in terms of the disciplining capacity of unemployment to restrain worker wage demands) is related to unemployment duration and at some point the long-term unemployed cease to exert any threat to those currently employed.

Consequently, they do not discipline the wage demands of those in work and do not influence inflation. The hidden unemployed are even more distant from the wage setting process. So we might expect that the short-term unemployment is a better excess demand proxy in the inflation adjustment function.”

But if they cant demand higher wages they will contribute to inflation through being less productive it seems.

Hi Bill,

Bank of England documents are candid on the different effectiveness of long & short-term unemployment in pushing wages down. Here`s an extract from the Bank`s August 2013 Inflation Report:

“The longer that people are out of work, the more their skills will deteriorate and as a result, the probability of them finding a job decreases – those who have been unemployed for over a year are, on average, around a third as likely to find work as the short-term unemployed. That is likely to mean that they will exert less downward pressure on wages and so the equilibrium unemployment rate in the medium term will remain elevated.”

Link: http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Documents/inflationreport/2013/ir13aug.pdf

And from the Annex of the December 1997 meeting of the Monetary Policy Committee:

“A41

The relationship between unemployment and earnings was then considered: in

particular, did short-term unemployment exert more downward pressure on earnings

than long-term unemployment?

A42

According to the British Household Panel Survey, the short-term unemployed

were more than twice as likely as the long-term unemployed to be employed a year

later. There were two possible reasons why the probability of employment declined

with unemployment duration. First, from any pool of unemployed workers, employers

would tend to select those with the strongest skills and most relevant experience first.

The long-term unemployed were thus less likely to have the most appropriate

qualifications and skills and were less likely to find a job. Second, the length of the

unemployment spell reduced the chances of becoming employed, because search effort

fell; or because skills, morale and motivation deteriorated; or because employers used

duration as a screening device to discriminate unfairly against the long-term

unemployed.

A43

Whatever the reason, the implications for the effect of long-term unemployment

on wage pressure were the same: when the proportion of long-term jobless was high,

for a given level of total unemployment, workers would probably realise that they

could not be replaced so easily, and hence that their bargaining strength was higher.

A44

The empirical evidence in general supported a more powerful role for short-term

unemployment in putting downward pressure on wages. Some studies suggested that

only short-term unemployment mattered. But recent Bank research had suggested

that, although short-term unemployment was more important, the potential downward

effect of long-term unemployment on wages should not be disregarded.”

http://web.archive.org/web/20130603031409/http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/minutes/Documents/mpc/pdf/1997/mpc9712.pdf

The Liberal Democrat politician and economist Chris Huhne, writing in the Independent in 1993 (“How to put the nation back to work” – 21 February 1993) outlined the particular problem of long-term unemployment as he saw it:

“A new initiative will be necessary now that long-term unemployment is rising again. Employers are more reluctant to hire people who have been out of work for a long time, and they in turn become demoralised. Like unsold flowers, they are moved further back in the florist’s shop, each time reducing their chances of sale. They fail to compete with those in work, so that there is a rise in the amount of unemployment needed to contain wages.”

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/business/economics-how-to-put-the-nation-back-to-work-1474387.html