I have received several E-mails over the last few weeks that suggest that the economics…

Employment guarantees enter the social inclusion debate

The Social Inclusion Research Paper series are slowly emerging. Professor Tony Vinson (Sydney University) was commissioned to write six papers on the topic and they are available HERE. In the paper on Jobless Families in Australia, he considers a range of strategies which have been advanced to reduce chronic joblessness which has wrecked families across Australia since the neo-liberal attack on full employment began in the mid-1970s. I was pleased to see him mention the Job Guarantee. This is what he said.

On Pages 5-6, Vinson writes:

Another strategy that has been discussed for some time is the creation of ‘public good’ jobs to provide work for the unemployed. A variant of that proposal has been presented by Mitchell (1998) who argues that if the private sector does not provide sufficient job opportunities to achieve full employment, then the government should guarantee a full-time or part-time job to everyone who desires one at the living wage level. There are many unfulfilled needs that could be met by Job Guarantee workers including environmental restoration, community services to the aged, youth, and the disabled, and other similarly useful activities. Watts and Mitchell (2000) believe such a program will generate a high rate of social return on public expenditure and reduce the unemployment rate to 2%. If it is assumed that these jobs are distributed pro-rata between the official unemployed and the hidden unemployed and a full-time salary level set at two-thirds of the average private sector rate, then Watts and Mitchell believe a multiplier effect will see an increase in consumption and work opportunities in the private sector … What Watts and Mitchell call ‘the arithmetic of the job guarantee’ is an impressive attempt to quantify pertinent variables. However, Argy believes that a cultural attitudinal change would not now see Australians supporting expenditures on a mix of supply-side and targeted demand-side measures without the requirement of reciprocal obligations from the jobless (for example, by searching very actively for work, retraining, relocating where possible and necessary, and with some penalties for non-compliance). This is a reminder that, in the final analysis, social values play a vital part in policy choices and that the question of the type of society we want to develop (or preserve) claims equal priority with the outcome of the policy sums.

More recent costings and analysis including a full operational plan for the implementation of a Job Guarantee can be found in our Creating effective local labour markets Report which we released last December.

So it might seem obvious that a focus on getting people back into work in the most direct way possible – that is, giving them a job – would be the best way of resolving social alienation. But, unfortunately, so far, not too many people of influence are focusing on that solution. Instead we are being arraigned with supply-side – blame the victim approaches. If someone is unemployed then they must not have enough skill or a positive enough attitude.

This can never be the reason for mass unemployment when there are too few jobs. Supply characteristics merely determine an individual’s position in the labour queue.

Policies that alter the distribution of skills and attitudes in the face of an economy that overall doesn’t produce enough work merely shuffle the queue of disadvantage. It is a fallacy to think that without enough jobs effective outcomes will result from relentless training schemes. In times when the macroeconomics job ration is binding, these expenditures are largely a waste of time and money.

So far, the social inclusion debate has been focused on the supply side. I hope it shifts to where it should be – employment creation – soon.

References

Mitchell, W.F. (1998) ‘The Buffer Stock Employment Model: Full Employment without a NAIRU’, Journal of Economic Issues, 32(2), 547-55.

Watts, M. and Mitchell, W.F. (2000) ‘The Costs of Unemployment in Australia’, mimeo, Centre for Full Employment and Equity, University of Newcastle.

Digression: Credit growth slowing

The RBA released the monthly financial aggregates today and of interest is the rapid restructuring of non-government balance sheets that is apparent.

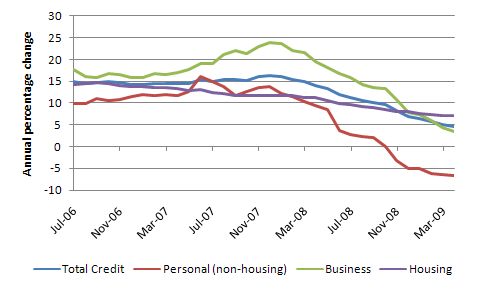

Credit growth has slowed significantly over the last 12 months. The following graph shows the annual percentage change in Total Credit, Housing, Other personal credit (excluding housing) and Business credit for the period July 2006 to April 2009. All components of credit growth have dropped significantly as the economy has weakened but personal credit is now falling in absolute terms (negative growth).

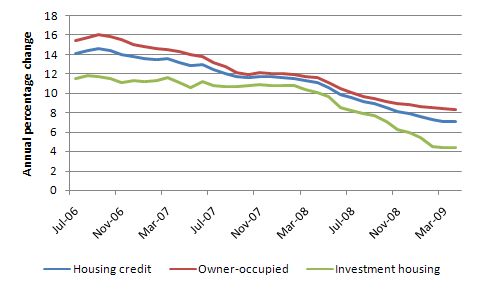

The next graph decomposes housing credit into owner-occupied and investment housing. Housing credit growth was 7.1 per cent in the year to April 2009 (but was 14.6 per cent per annum in September 2006). The chart shows that owner-occupier credit growth dominates the investment housing demand for funds.

Overall, this fits with the last National Accounts data which showed that households sharply increased their saving rates. When next week’s National Accounts data comes out I expect that trend to be even stronger as households try to reduce their exposure to credit and job loss.

What this also tells us is that the budget deficits are now starting to underpin a much healthier non-government financial situation where net saving can occur. It is also has ended the reliance that we have had on piling up ever increasing levels of debt onto households to ensure that the spending gap (derived from the budget surpluses) is filled.

Saturday Quiz

The Saturday Quiz will be once again available sometime tomorrow.

That must be heartening for you Bill. Let’s hope the time is at hand when the government at least gives it a try.

I am currently reading (skimming through) “Milton Friedman: a guide to his economic thought”. I notice he does agree with a few things such as floating exchange rates. Unlike so many economic commentators today, he recognises the existence of a central monetary authority that creates currency through spending. But his social outlook is appalling and despicable. And he rejects the notion of trying to create full employment, arguing that this always fails in the longer term, though he does not touch on anything like the job gaurantee idea. I take it that this bloke’s theories are the origin of the idea of a NAIRU?

Dear Lefty,

The natural rate of unemployment and the NAIRU are not the same thing.

The NAIRU is part of a Keynesian model (by Franco Modigliani)l and the natural rate theories are more in line with a Walrasian General Equilibrium model (Friedman and Phelps).

Hope that helps.

cheers, Alan