I have received several E-mails over the last few weeks that suggest that the economics…

Declining wage shares undermine growth

There was an interesting Working Paper issued by the ILO – Is aggregate demand wage-led or profit-led? – last year, which finally received some coverage in the mainstream economics press this week. The Financial Times article (October 13, 2013) – Capital gobbles labour’s share, but victory is empty – considered the ILO research in some detail. That lag is interesting in itself given that it was obvious many years ago that the trends reported in the ILO paper and the FT article were part of the larger story – that is, the preconditions – for the global financial crisis. If you look back through the Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) literature, dating back to the 1990s, you will see regular reference to the dangers in allowing real wages to lag behind productivity growth. It seems that the mainstream financial press is only now starting to understand the implications of one of the characteristic neo-liberal trends, which was engendered by a ruthless attack on trade unions by co-opted governments, persistent mass unemployment and underemployment, and increased opportunities by firms to off-shore production to low-wage nations. Better late than never I guess.

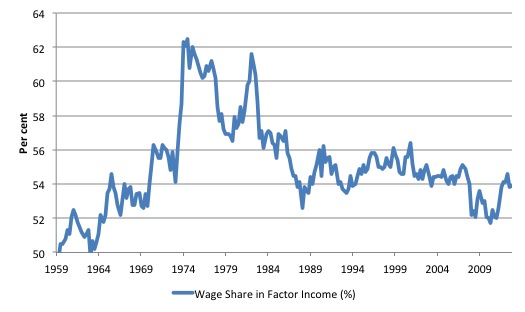

Here is the labour share in factor income for Australia from the September-quarter 1959 to the June-quarter 2013. The downward trend since the 1980s is representative of similar trends in many advanced nations.

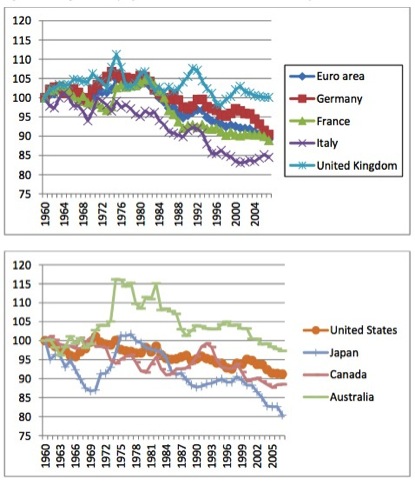

The ILO presented the following graphs (first two panels of Figure 1, Page 5), which I reproduce to put the Australian data in context. As an aside, for an official document, the formatting inconsistencies of the ILO graphs is somewhat poor. At least the vertical scales are comparable.

Their graphs are indexed at 100 at 1960 to make them comparable across jurisdictions.

The authors note that:

There has been a significant decline in the wage share in both the developed and developing world along with neoliberal policy reforms following the 1980s. The promise of these reforms was to stimulate private investment and exports, which in turn was expected to generate higher growth, more jobs and trickle down effects.

The question is whether these growth dividends have been sufficient to repay the workers for the sacrifice they have made in terms of wage share.

I have considered this topic in these blogs – There is a class warfare and the workers are not winning and Massive real wage cuts will not improve growth prospects and The origins of the economic crisis.

Another recent ILO Report written by Englebert Stockhammer – Why have wage shares fallen? A panel analysis of the determinants of functional income distribution – is also worth reading for its analysis of trends in the advanced OECD nations.

[Reference: Stockhammer, E. (2013) Why have wage shares fallen? A panel analysis of the determinants of functional income distribution, International Labour Office, Geneva]

There are two broad facts that are agreed by most analysts in this area/ First, up until the early 1980s, real wages and labour productivity typically moved together. As the attacks on the capacity of workers to secure wage increases intensified, a gap between the two opened and widened.

The widening gap between real wages and productivity growth manifested as the rising profit share and the wage share in national income has fallen significantly over the last 35 years in most nations.

Second, in the Anglo nations, “a sharp polarisation of personal income distribution has occurred” (Stockhammer, 2013: 2), with the top percentile and decile of the personal income distribution substantially increasing their total shares. The munificence gained at the expense of lower-income workers manifested, in part, as the excessive executive pay that emerged in this period.

To fix ideas some revision is necessary. Regular readers will know all this so you can skip to somewhere below.

The real wage is the purchasing power equivalent on the nominal wage that workers get paid each period. To compute the real wage we need to consider two variables: (a) the nominal wage (W) and the aggregate price level (P).

The nominal wage (W) – that is paid by employers to workers is determined in the labour market – by the contract of employment between the worker and the employer. The price level (P) is determined in the goods market – by the interaction of total supply of output and aggregate demand for that output although there are complex models of firm price setting that use cost-plus mark-up formulas with demand just determining volume sold.

The real wage (w) tells us what volume of real goods and services the nominal wage (W) will be able to command. For a given W, the lower is P the greater the purchasing power of the nominal wage and so the higher is the real wage (w).

We write the real wage (w) as W/P. So if W = 10 and P = 1, then the real wage (w) = 10 meaning that the current wage will buy 10 units of real output. If P rose to 2 then w = 5, meaning the real wage was now cut by one-half.

The relationship between the real wage and labour productivity relates to movements in the unit costs, real unit labour costs and the wage and profit shares in national income.

The wage share in nominal GDP is expressed as the total wage bill as a percentage of nominal GDP. Economists differentiate between nominal GDP ($GDP), which is total output produced at market prices and real GDP (GDP), which is the actual physical equivalent of the nominal GDP.

To compute the wage share we need to consider total labour costs in production and the flow of production ($GDP) each period.

Employment (L) is a stock and is measured in persons (averaged over some period like a month or a quarter or a year.

The wage bill is a flow and is the product of total employment (L) and the average wage (w) prevailing at any point in time. Stocks (L) become flows if it is multiplied by a flow variable (W). So the wage bill is the total labour costs in production per period – that is W.L

The wage share is just the total labour costs expressed as a proportion of $GDP, that is:

(W.L)/$GDP

This is usually expressed as a percentage (as in the graph above although note the graph is about GDP at factor cost – a complication we will ignore here).

We can break this down further, by noting that labour productivity (LP) equals the units of real GDP per person employed per period. Using the symbols already defined this can be written as:

LP = GDP/L

Nominal GDP ($GDP) – that is, at market value or current prices can be written as P.GDP, where the P values the real physical output. This is different to real GDP which nets out the effects of price level changes on our measure of economic activity.

By substituting the expression for Nominal GDP into the wage share measure we get:

Wage share = (W.L)/P.GDP

We can write this in equivalent terms as:

Wage share – (W/P).(L/GDP)

Now if you note that (L/GDP) is the inverse (reciprocal) of the labour productivity term (GDP/L).

So an equivalent but more convenient measure of the wage share is:

Wage share = (W/P)/(GDP/L) – that is, the real wage (W/P) divided by labour productivity (GDP/L).

The point of all this torture is that it produces a very easy to understand formula for the wage share.

It becomes obvious that if the nominal wage (W) and the price level (P) are growing at the pace the real wage is constant. And if the real wage is growing at the same rate as labour productivity, then both terms in the wage share ratio are equal and so the wage share is constant.

The wage share was constant for a long time during the Post Second World period and this constancy was so marked that Kaldor (the Cambridge economist) termed it one of the great “stylised” facts. So real wages grew in line with productivity growth which was the source of increasing living standards for workers.

The productivity growth provided the “room” in the distribution system for workers to enjoy a greater command over real production and thus higher living standards without threatening inflation.

Since the mid-1980s, the neo-liberal assault on workers’ rights (trade union attacks; deregulation; privatisation; persistently high unemployment) has seen this nexus between real wages and labour productivity growth broken. So while real wages have been stagnant or growing modestly, this growth has been dwarfed by labour productivity growth.

As a result, the wage shares in most nations have been falling. Where has the real income gone? To the profit share, silly!

The ILO Working Paper noted in the introduction adds to this sort of analysis because it “estimates the effects of a change in the wage share on growth in the G20 countries using a post-Keynesian/post-Kaleckian model” and attempts to calculate “the global multiplier effects of a simultaneous decline in the wage share”.

So what that does mean?

The ILO paper notes that there are two competing views about what drives economic growth:

Mainstream macroeconomic models emphasize the supply side rather than the demand side of the economy; and assume that demand will follow supply. Most importantly for the purpose of this paper, they treat wages merely as a component of cost, and neglect their role as a source of demand. On the contrary, post-Keynesian/post- Kaleckian models … reflect the dual role of wages affecting both costs and demand, and while they accept the direct positive effects of higher profits on investment and net exports emphasized in mainstream models, they contrast these positive effects with the negative effects on consumption.

This sort of division among economists goes back to the debates in the C19th between Marx, who understood that if you cut wages you would not only cut costs but also income and the likely effect would be to undermine total spending, and the conservatives of the day (Ricardo, Mill, Say etc) who considered that wage cuts would increase supply and demand would follow.

The debates saw a more modern form during the 1930s when Keynes attacked the conservative Treasury view by emphasising the duality of wages – a cost and an income. The Treasury View dominated in the early days of the Great Depression and inspired wage cuts, which only made the unemployment higher.

The ILO Paper notes that if the wage share falls then we would expect to see a decline in total consumption because “the marginal propensity to consume out of capital income is lower than that out of wage income”.

Interestingly, the FT article begins with an amusing anecdote. It says:

In 1958, Walter Reuther, a powerful US union leader was taken on a tour of a newly automated Ford Motor plant. “Aren’t you worried about how you’re going to collect union dues from all these machines?” he was asked by a (no doubt smug) company manager.

“The thought that occurred to me,” Mr Reuther replied, “was how are you going to sell cars to these machines?”

So where will growth come from in this context? The ILO paper says that a lower wage share may stimulate investment because profitability is higher and firms typically use internal fans to finance investment expenditure.

It is also possible that a lower wage share will be associated with increased external competitiveness which may stimulate net exports.

In other words:

… the total effect of the decrease in the wage share on aggregate demand depends on the relative size of the reactions of consumption, investment and net exports to changes in income distribution. If the total effect is negative, the demand regime is called wage-led; otherwise the regime is profit-led. Whether the negative effect of lower wages on consumption or the positive effect on investment and net exports is larger in absolute value essentially becomes an empirical question.

So that is an interesting research programme.

I won’t go into the statistical techniques that the ILO paper uses but clearly you can read about them yourselves if you are interested. Their work focuses “on the sixteen major developed and developing countries, which are members of G20: European Union, Germany, France, Italy, UK, US, Japan, Canada, Australia, Turkey, Mexico, South Korea (henceforth Korea), Argentina, China, India, and South Africa.”

The principal findings are:

1. “a rise in the profit share leads to a decline in consumption” because larger “consumption propensities” out of wage income are “confirmed in all countries”.

2. “The US is the only developed country where the profit share has no significant effect on investment”.

3. “In most developing countries the profit share has no statistically significant effect on private investments”.

4. “The effect of the profit share on private investment in China is also insignificant …”

5. “Even in the East Asian countries like Korea and China that have high investment rates, private investment is not driven by high profits but the business environment created by industrial policy and public investment, which explains the lack of statistically significant correlation between private investment and profits.”

6. “In all countries, GDP has a strong and significant effect on private investment, providing evidence for the significance of an investment-growth nexus” – in other words, economies that are growing strongly provide a fertile environment for private investment. Austerity-ridden economies undermine private investment. Economies where consumption is falling due to real wage suppression also do not provide a buoyant investment climate.

7. “… in three developing countries (Korea, India, and China) public investment has a significant positive effect on private investment”.

8. “The negative effect of the increase in the profit share on private consumption is substantially larger than the positive effect on investment in absolute value in all countries. Thus demand in the domestic sector of the economies is clearly wage led; however, the foreign sector then has a crucial role in determining whether the economy is profit-led”.

9. “Overall demand in the Euro area (12 countries) is significantly wage-led … +Germany, France, and Italy as individual large members of the Euro area are also wage led … The UK, US, and Japan are also wage-led … Canada and Australia are profit-led; as small open economies the net export effects are high; the investment effects are also among the highest in the developed world in these two countries, and the differences in the marginal propensity to consume out of profits and wages are among the lowest.’

These results (Point 9) would suggest that there are no growth implications in Australia for the redistribution of income away from wages towards profits.

However, every study has its weakness and in this case there are severe limitations of the analysis as far as Australia is concerned. The same limitations apply for all nations but I’ll just briefly discuss Australia in this case.

The sample period chosen for the study includes the atypical period where household debt skyrocketed from X percent 2X percent of disposable income in a matter of 10 or 12 years.

Data from the RBA statistics archive – Household Finances – Selected Ratios – B21 shows that in March 1977 the Household Debt to Disposable Income ratio was 33.5 per cent.

As the financial system opened (floating of AUD, deregulation of mortgage interest rates, and relaxing capital controls), the ratio rose to 42.9 per cent 10 years later (March 1987).

Then the gap between real wages and productivity started to rise as the wage share was suppressed.

By March 1997, the household debt ratio was 73 per cent and the financial planners were coming out to play exploiting the slack rules about product disclosure and the fact that the capacity of households to maintain consumption growth out of real wages growth was declining.

The credit boom that followed saw the Household debt ratio peak at 153.3 per cent in September 2006 as the warning bells of the impending financial crisis were starting to toll. By then the interest payments out of disposable income had risen from 5.3 per cent to 11.1 per cent, squeezing the capacity of the households to purchase other goods and services.

The limitation of the ILO analysis in this regard is that the observed results they gain for the so-called “profit-led” economies ignore the fact that consumption was being propped up beyond what it might otherwise be because of the rapid and unsustainable credit growth.

So not only was the differences in the consumption propensities (how much out of each extra dollar is consumed) between wage income and profit income not as magnified in Australia as elsewhere but the real rate of GDP growth was stronger than otherwise, which also led to a more favourable investment response.

But as is clear now, the credit binge produced unsustainable household balance sheets and is now over. the household saving ratio is now back around 10% and rising after being negative in the years leading up to the financial crisis.

Whether it gets back to its prior’s steady average of around 16 per cent remains to be seen and the continued suppression of real wages growth and the mass labour underutilisation rates may prevent that.

But the point is that the growth environment is significantly different now than it was when households were piling up the debt. I suspect that the ILO results will be different if the researchers revisit the project in a few years time when the post-credit binge data sample is longer.

Further, in the case of Australia we had a massive depreciation in the exchange rate in the latter part of the 1990s, which provided for a favourable net export environment.

The FT article quotes a financial market economist as musing:

… whether Marx was right all along, and that capitalism ultimately sows the seeds of its own destruction, “when there is no consumer demand and it all falls over”.

Conclusion

The declining wage share and the resulting credit binge in many nations were clearly causal in creating the global financial crisis. The mainstream economists believed that the markets were efficient and that there would be no problems with placing an increasing proportion of real income into the hands of the Casino economy.

They were wrong but then just this week we have learned that one of the leading contributors to the “efficient markets” literature, who is also one of the most vocal proponents of the free market myth, was just awarded a Nobel Prize in Economics (Fama).

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

The exchange with Walter Reuther reminded me of Proudhon in System of Economic Contradictions:

Also, that book contains one of my favourite quotes:

Which, of course, sums up mainstream economics very well — nothing much has changed since 1846!

Iain

An Anarchist FAQ

The ILO’s claim that a decling share for labour reduces demand because labour’s propensity to consume is larger that capital’s is dodgy. It’s true for a GIVEN DEFICIT. But as every MMTer knows, government can expand or contract a deficit to any extent it likes (or implement other stimulatory measures, like interest rate cuts or QE – not that I’m saying QE too clever). So if labour’s share declines (and I’m not arguing that is desirable), any intelligent government ought to be able to compensate for the reduced demand by raising the deficit.

Likewise it could well be that public sector workers have a different propensity to consume as compared to private sector workers. But that’s not an argument for expanding or contracting the public sector.

Dear Bill

One negative consequence of a falling share of labor’s income is that producers will try to find buyers abroad. That’s what the Germans and Chinese have done. Despite depressed domestic consumer demand, they can employ most of their people because they import demand. Actually, in the case of China, most demand comes from investment rather than from exports. The Germans could be successful only because of a common currency with most of the other EU countries. The problem with using exports as a source of demand is of course that it is a return to a mercantilistic world in which every country tries to create jobs at the expense of everybody else. Wage moderation and mercantilism go hand in hand.

Regards. James

“any intelligent government ought to be able to compensate for the reduced demand by raising the deficit.”

… but they can’t necessarily make private companies hire, in much the same way lower interest rates don’t necessarily persuade individuals to borrow. This is what happened in the US post-stimulus, with corporations happy to pocket the added demand as profits (as a free ride), without taking the baton and doing their part by increasing job creation.

apj, persuading individuals to borrow is usually just a side effect of low interest rates. Their main purpose is to persuade businesses to borrow.

Any sufficiently large stimulus will result in private companies hiring people.

Isn’t this just a discussion about realisation crises? It’s obvious that if wage share decreases globally then there will be more goods (in $) than there is money to buy them, unless capitalists suddenly decide they want to buy up all the surplus stock that they made. Increasing inventories and debt levels is not sustainable and ultimately government needs to fill the gap.

Mike –

If there are more goods available than money to buy them, doesn’t that mean the profit margin’s too high? And that those capitalists can cut their prices to sell more stock?

The nice thing about economics is that most problems are eventually self correcting.

The nasty thing about economics is the damage caused while waiting for the problems to correct themselves. But these are usually easy for governments to overcome.

I’d argue a falling wage share is a good thing overall. It enables governments to increase spending and/or cut interest rates, and it is good for competition because it ensures prices can be cut to sell more goods.

Bill –

Do you actually know this? Or is it just an assumption?

It would be interestinng to know exactly where it has gone, as there’s quite a lot of places it could go. Apart from going to the owners it could go to:

Finance

Land rent

Tax

Intellectual property

…and of course there are a lot of B2B transactions for products and services, many of which now come from overseas.

So why are you treating it as profit v labour? Is it just because you’re a fan of Marx?

“I’d argue a falling wage share is a good thing overall. It enables governments to increase spending and/or cut interest rates, and it is good for competition because it ensures prices can be cut to sell more goods.”

The government / Central bank can cut interest rates and / or increase spending regardless of the wages share of income.

You really have no idea.

Bill said: “As a result, the wage shares in most nations have been falling. Where has the real income gone? To the profit share, silly!”

This has been backed up many, many times by Bill using graphs and real data.

Aidan’s reply: “Do you actually know this? Or is it just an assumption?”

%&$$ yourself.

[Bill edited the first of the last two words maintaining string-length and coding integrity]

https://billmitchell.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2010/10/Australia_real_wages_productivity_1978_2010.jpg

It looks simple enough to understand but Aidan keeps demonstrating otherwise.

Aidan,

Finance is profit for Banks / Investors.

Land rent is profit for Landowners.

Tax has not increased for businesses (how can you even ENTERTAIN that notion?)

Intellectual property (Grasping at straws, aren’t we?)

Point is, ACTUAL WORK-ers are getting screwed (and just so we’re not bombarded with the typical bullsh!t, many, MANY very small business owners can be classed as workers for the purpose of this exercise due to the time, effort and miniscule take-home they often end up with, I’m just so sick of hearing about them as if they are in any way the class of people we are all complaining about, if anything they are proof that hard work rarely equals big dollars in the so-called “free market).

And if it wasn’t bad enough that labourers in the primary and tertiary industries in Australia are getting screwed in favour of huge profits, the slave-class of impoverished “free trade” nations like China/Bangladesh/India etc. are copping it in a way that nearly warrants the death penalty for some of the a$$holes who deliberately set up these arrangements (there are those who are coerced into doing this as a job and shame on them too but it is their masters need to be punished).

No one with 2 or more brain cells can feel good about where we are as a species right now.

Alan Dunn –

Not without increasing inflation.

Even in the current economic circumstances they wouldn’t be able to increase spending as much without increasing inflation significantly.

As for the graph I understand perfectly, but I draw different conclusions about its implications. Wage share has fallen substantially, but was unsustainably high to begin with, and the changing nature of business (with prices becoming less proportional to the labour inputs) meant that the ratio had to keep falling. Whether it had to fall as much as it did I don’t know (hence I’d be interested in a detailed breakdown of the non wage share) but the only reason the macroeconomic effects aren’t entirlely positive is that governments have failed to take the opportunity to spend more (and in Australia’s case, interest rates have been set too high).

Jeff,

No, it’s income for banks/investors, but banks have costs too. Finance costs depend substantially on where the central bank has set the interest rate.

I conced that point, but I’d still like to See it treated separately because it adds nothing to the productive economy.

I live in Australia where nearly every new governemt imposes new taxes on business. They do remove taxes as well, but while there’s a widespread assumption that the tax burden for business is falling, I’ve not seen any actual proof.

On the contrary, its total value has grown substantially and that trend is likely to continue.

You seem to be conflating two separate issues here. There is a big problem in these countries: there are many instances of the law of the land not being properly enforced, and because of that some workers are being treated appallingly. But even if those abuses are entirely prevented from occurring, it will not change the fact that stuff manufactured in those countries is very cheap. And that is because wages are low there. But they’d probably be substantially lower if they werent selling so much of that stuff to us. Free trade is a good thing. Concentrating on genuine high value activities is much better than distorting the domestic market so that we pay more for low value things.

Aidan,

You asked

\”So why are you [i.e. Prof. Mitchell] treating it as profit v labour? Is it just because you’re a fan of Marx?\”

It\’s my understanding that GDP is divided into wages and profits: every dollar going to one of them, cannot go to the other. In other words, it\’s a matter of distribution.

=======

While I don\’t speak on anybody\’s behalf, in my opinion, this explains at least partially Prof. Mitchell\’s views.

In any case, you have every right to ask that question, let\’s be clear. But then, it is also fair, for me, to ask why are seem to believe profit is not opposed to labour? Do you have any reason to believe otherwise?

To return to the “MMT issue” of deficit-spending when a decline in the wage share leads to weak aggregate demand: of course it can be done (except in the euro zone given today’s rules). There must nevertheless be a distinction between the distribution of the cake (profits/wages) and the size of the cake (GDP). So, an increase in government spending “cures” an aggregate demand problem, but does not necessarily change the distribution shares. Government money might finance projects build by private firms, not changing profit and wage shares. This might happen to a country that is a net exporter, so that your second-best policy intervention (deficit spending because you cannot control real wages directly) ends up prolonging export-induced beggar-thy-neighbour problems elsewhere (Japan). Higher real wages, as has been pointed out above, has been an inducement to invest in machinery, and this has led to higher productivity and higher GDP. That cannot be emulated by deficit spending. Just because it is sustainable doesn’t mean it’s optimal.

Magpie – if GDP doesn’t include anything other than profits and wages (can Bill confirm or deny this) then that’s a severe limit on its usefulness.

Could you please rephrase your question? I’m not sure what you mean.

Dirk – changing distribution shares shoudn’t be the objecive nor the way to get there, although it could be a side effect of either of those.

Japan’s problems are caused by things like avoiding awkward questions and by its sales tax, not its high net exports.

Deficit spending doesn’t induce investment in machinery, but lower interest rates do.

“Deficit spending doesn’t induce investment in machinery, but lower interest rates do”

And for that comment I sentence you to serving five years in a real business until the blinkers drop off.

Aidan

“Magpie – if GDP doesn’t include anything other than profits and wages (can Bill confirm or deny this) then that’s a severe limit on its usefulness.

Below are the main categories, which added up together, form GDP (according to the ABS, 5206. Table 7. Income from GDP. current prices):

Total compensation of employees +

All sectors Gross operating surplus +

Gross mixed income +

Total factor income +

Taxes less subsidies on production and imports +

Statistical discrepancy (I) +

—————————–

= GROSS DOMESTIC PRODUCT ;

Quick notes:

(1) Gross mixed income is profit + wages for the self-employed and non-incorporated business (they don’t need to declare profits and wages separately, so they provide a single figure).

(2) All sectors gross operating surplus = Total corporations GOS + General government GOS + Dwellings owned by persons GOS

“Could you please rephrase your question? I’m not sure what you mean.”

A rephrase: The sum above gives a quick and dirty explanation why profits and wages exhaust each other: given a constant GDP, one extra dollar going to profits means one less dollar going to wages and, vice versa, an extra dollar spent in wages means one less dollar left for profits.

What reason, if any, you have to believe this is not so?

“Deficit spending doesn’t induce investment in machinery, but lower interest rates do”

And for that comment I sentence you to serving five years in a real business until the blinkers drop off.

A just and proportionate sentence. As Professor L.W.Wray has said, if there is no demand,and therefore market, lower interest rates are irrelevant.

Back here( in the uk lucky country that dodged the euroexstacy suicide pill ) we have had low base interest rates for about 5 years.

I like this one from the ONS

The only asset or sector which showed positive growth in Q2 2013 when compared with Q2 2012 was intangible assets (0.3%).

The funny thing is retail rates have exploded for the poor, desperate and potentially productive.

The wholesale rates for the global megafauna/rentier/extractive class have diminished to opportunity level, smash and grab level.

Ladies and gentlemen, I give you the royal mail privatisation

paul –

If there were no demand then higher wages wouldn’t help either – they’d just result in more people out of work.

I am not claiming lower interest rates are a universal substitute for government deficit spending. Bill’s already shown conclusively that they’re not.

Neil seems to think that all businesses operate the same way. I do not. I’m well aware that there are plenty of businesses that wouldn’t invest in more equipment if it were cheaper to do so. But there are also many business which woudn’t invest more in equipment if labour costs were higher. But in each case many will.

Magpie –

In terms of GDP they exhaust each other. But to draw meaningful conclusions about the effect, you have to look at where the money us actually going. That includes separating out things that are lumped together in GDP, and it also includes things that ar excluded from GDP.

Aidan,

“But to draw meaningful conclusions about the effect, you have to look at where the money us actually going. That includes separating out things that are lumped together in GDP, and it also includes things that ar excluded from GDP.”

The way presented by ABS is where the money is actually going: money basically goes to wages and profits (that is, total factor income).

So, what are the things that need to be separated out or that are excluded from GDP but should be taken into account?

“Deficit spending doesn’t induce investment in machinery, but lower interest rates do.”

…and he’s never read Keynes’ General theory either. Awesome.

Alan Dunn –

I thhought I had. Have I missed a bit? Where exactly does it contradict that statement?

Or are you mistakenly assuming that I’m claiming lower interest rates are better for restoring demand? If so, let me clarify: lower interest rates are not generally better at restoring demand than deficit spending. Though there are some specific instances where they’re better for restoring demand (including, I believe, Australia since 2010) their scope is far more limited.

When I said lower interest rates induce investment in machinery, it was in response to Dirk’s claim that higher wages boost productivity more than deficit spending because the latter doesn’t induce investment in machinery. It is implicit in these statements that sufficient action is taken to prevent demand remaining depressed.

And as Keynes pointed out in GT ch11, the decisions are taken on the basis of prospective interest rates rather than actual interest rates. But I consider that to be only a minor difference in the context of this discussion.

Magpie –

So, what are the things that need to be separated out or that are excluded from GDP but should be taken into account?

Things that need to be separated out:

Land rent (because it adds nothing to the productive economy)

Intellectual property (because f its replicability and the rapid growth in its value)

Things not in GDP that should be taken into account

Imports

Tax

Wholesale cost of finance

And the ratio of profits:wages:other costs needs to be investigated for all businesses, not jjust the average

“Neil seems to think that all businesses operate the same way. I do not.”

The difference is that Neil knows, because Neil earns a living looking at businesses.

One of the advantages of being freelance in my trade is that you get to go around lots and lots of businesses and understand how they actually operate.

In all cases what determines investment expansion is one thing and one thing only.

Sales.

Dear Magpie and others

Re: Distribution of Income

There are more claimants on real income than labour and capital. Government also clearly makes a claim, so you cannot immediately assume that if the labour share is falling, it must mean the profit share is rising. It could be the government share is rising.

You also have to be careful about the measures you use. Some exclude the government share while others include it.

The fact is that in Australia, almost all of the fall in the labour share has been taken up by a rise in the profit share over the last 20 years or so.

best wishes

bill

If there were no demand then higher wages wouldn’t help either – they’d just result in more people out of work.

I cannot envisage any situation where ther is no demand, so i don’t see your point.

The problem lies in the decreasing ability of a large section of the population to express that demand through spending. As wages are the main mechanism to enable this, higher wages would indeed allow this.

Hi Aidan,

I know too well the unpleasant feeling of holding the minority opinion in a discussion such as this, so let me make clear that I write this with good, constructive intent.

Please read some Minsky. Please. I would argue from a reading of Minsky that a rising profit share is more inflationary.

Much of the spending of the modern firm has distributed to sources of greater inflationary potential. Think of how much the typical large corporation now spends on marketing, corporate legal teams (think IP) and lobbyists. Note that this results in a shift of distribution away from material inputs and productive labour. This spending does not result in increased productive output and is either passed on to the consumer through increased prices or through a reduction of labour costs in other areas (i.e. wage cuts/stagnation for those workers who cant really do anything about it). These practices are increasingly becoming the norm, given the need for corporations to maintain their market power in the 21st century. This spending also generates demand without an associated product to be bought by consumers, which reduces the inflationary threshold of an economy.

And of course the same applies for rent/profit. Profit is income generated through ownership, not productive output and comes with the all same drawbacks. (I would also argue the same case against an increase large, expensive capital good investments, but that’s a whole other story.)

With that in mind, a falling wage share and rising profit share is really quite insidious. Not only does it reduce the real wage, relying on private debt to paper over the demand gap, but it reduces the level of demand required to outstrip output. Mainstream economists then come in wielding concepts like the NAIRU and use them to deal further blows to labour.

Neil Wilson –

I’d expect different businesses to behave in different ways, and for that method of operation to be very common in small businesses but rare in big businesses (and almost nonexistent in well run big businesses.)

What proportion of those businesses that wouldn’t invest more in equipment if interest rates were lower do you think would do so if wages were higher?

Andrew –

A rising profit share may be more inflationary in the short term, but businesses have a lot more control over their prices than they do over their wages. If demand drops (not necessarily because of a widespread drop in demand; it could just as easily be from increased competition) then businesses can cut their margins until it increases again, instantly reversing the past inflationary effects. Whereas once wages rise, it’s very difficult to get them to fall again.

Is there any particular bit of Minsky’s work you’re referring to?

A falling wage share doesn’t necessarily reduce the real wage, and rising land rent is likely to be a bigger threat to real wages.

paul –

Well if you can’t see my point, could you see the point of your quoting of Professor L.W.Wray’s claim that

?

I didn’t think it was meant to be taken quite so literally, so my point was if demand collapses then higher wages wouldn’t help either – they’d just result in more people out of work. Increasing wages wouldn’t erode demand because businesses would be laying off workers so in the absence of government intervention, aggregate wages would fall.

Under normal circumstances, higher wages do support demand. But the important thing is that the demand is there, not where it comes from.

“I’d expect different businesses to behave in different ways”

Perhaps it is time for you to stop expecting and start finding out what really happens by getting in there and finding out.

What happens in *all* businesses – large and small – is that they talk about sales – a lot. That is all that matters because without sales the business closes.

Any theory of the firm that fails to start with sales is not how it works in the real world and therefore largely irrelevant IMV.

When I go into any business – large or small – I can identify inefficiencies and potential cost savings almost instantly.

What that tells you is

(i) businesses collect organisational entropy over time, and the bigger and older the business generally the more the entropy and the more cost saving and streamlining opportunities there are. Big businesses are stunningly inefficient – because politics quickly overtakes survival as the primary goal.

(ii) businesses don’t really worry about costs in absolute terms. They worry about whether the volume of their sales is sufficient, and hopefully whether each sale is generating a contribution. In very many growth stage businesses they won’t even worry about whether the margin is sufficient – convinced that they can do something about that once they have ‘economies of scale’. Hence you get businesses like Twitter.

(iii) cash cow businesses invest as required on replacement capital to retain the existing customer base. As the business is solid and profitable, again there is little focus on cost control and efficiency. In general it is party time and the business just enjoys being relatively successful. These businesses get sold a lot, and that usually generates short term cost control and staff freeze measures – which disappear as soon as there is a sniff that it is affecting sales.

(iv) dog businesses invest rarely and ‘make do and mend’ – utilising obsolete capital for as long as humanly possible. Long after their amortization value on the accounts has expired. Here it is about survival and cost cutting measures are rife. But there is rarely any debt left on the books at this point, unless you are propping up a business that is inevitably going to fail.

Now this is all micro, but I have yet to see any rational aggregation argument that makes what productive businesses actually do that sensitive to interest rates in any direct fashion.

Only hyper leveraged operations can have their cost structures so altered by interest rate changes that it makes a noticeable difference. And that means that the effective channels have to be property speculation and leveraged buyout asset strippers.

Neither of which should be encouraged, nor relied upon.

yes wages declining share of national wealth is the heart of our economic difficulties

the long macroeconomic failure of our times

very interesting Japan’s graph being the weakest

a country with a relatively high government sector deficit

and a relatively low unemployment rate

although I understand a job guarentee could only make things better

it is surely not inconceivable that this trend could continue with the guarentee

in place so successful has the very wealthy’s battle for surplus value been

I think the state sector has to exercise its monetary power in many ways

and regulate meaningful minimum wage with some kind of top up income

and limit the free flow of labour and invest in well payed jobs for the public

purpose

Japan may show that relatively high deficits and low unemployment levels

are not enough to organise an economy for the benefit of all