The – Battle of Sedan – in September 1870, was a decisive turning point in the relationship between France and Germany, which still resonates to this day and has influences many subsequent historical developments. When I was researching my 2015 book – Eurozone Dystopia: Groupthink and Denial on a Grand Scale (published May 2015) –…

Options for Europe – Part 26

The title is my current working title for a book I am finalising over the next few months on the Eurozone. If all goes well (and it should) it will be published in both Italian and English by very well-known publishers. The publication date for the Italian edition is tentatively late April to early May 2014.

You can access the entire sequence of blogs in this series through the – Euro book Category.

I cannot guarantee the sequence of daily additions will make sense overall because at times I will go back and fill in bits (that I needed library access or whatever for). But you should be able to pick up the thread over time although the full edited version will only be available in the final book (obviously).

[PRIOR MATERIAL HERE FOR CHAPTER 1]

[NEW MATERIAL TODAY]

The EMS ‘second life’ marked by increasing Franco-German acrimony as they march together towards Maastricht

The Bundesbank effectively forced the devaluations on the French Franc in the early years of the EMS by refusing to support it by reducing its own interest rates to quell the outflow of capital from France. By giving primacy to the Monetarist position on inflation, Germany became the authority in Europe. It is argued that the growing acceptance of the primacy of ‘price stability’ among French politicians on both sides of politics was a reflection of their desire to regain the semblance of French leadership in Europe (Baun, 1996). de Boissieu and Pisani-Ferry (1995: 23) note that “only a low-inflation, stable-currency France could pretend to some form of leadership in Europe” and “maintaining France’s status within the EC and within the so-called French-German couple” required them to fall into line. So the ambitions of the French political class for their reward for “rigueur: power” (de Boissieu and Pisani-Ferry (1995: 23) became an objective in itself and the costs to the citizens in the form of suppressed real wages and rising unemployment was subsidiary, at best. Mitterand “made the choice of giving priority to France’s European commitments over his own initial economic program in 1983” (de Boissieu and Pisani-Ferry, 1995: 23). This divergence in motivations of the political class and the well-being of the citizenry is now the norm in modern Europe.

In effect, the decision by the EMS Member States to peg against the Deutsche Mark, meant that the Bundesbank became the central bank for the EEC (Hetzel, 2002: 50). The other nations subjugated their own policy independence. For all of France’s historical concerns for maintaining sovereignty and rejecting supra-national European institutions, it took the socialists in 1983 to give up that freedom and then not to Brussels but to Germany – of all nations. As we will see, once the Germans had won that ‘war’, the French were became increasingly motivated to support a separate European Central Bank to wrest some control back from Germany.

After France began to toe the ‘correct’ ideological line, the longed for ‘convergence’ in economic policies and outcomes began to emerge and the currency instability reduced. While some of these developments are clearly the result of the growing uniformity of economic policies among the Member States, there were external developments that helped reduce the pressure on the Deutsche Mark and, hence, the other European currencies. The election of Ronald Reagan to the US Presidency in 1981 warmed the cockles of the neo-liberal ideologues, the reality was that his Administration introduced an old-fashioned ‘Keynesian stimulus’, which promoted strong economic growth following the severe recession in 1982. The ideologues were seemingly blind to the fact that what was working for the US was exactly what they loathed. The smoke and mirrors was a reversal of the old adage ‘do as I say not as I do’.

The US dollar strengthened through the first years of the 1980s and there was large capital inflows to the US in response to the favourable investment climate, supported by an “expanding ‘structural’ component of the US budget deficit” (BIS, 1985: 8). While there were some adverse effects in Europe as their imports became more expensive they were “more than offset by the benefits bestowed on the rest of the world by the locomotive rôle of the US economy, without which there would have been no recovery in world trade” (BIS, 1985: 9). Given the restrictive policies in Europe, the rise in unemployment rates would have been much worse had not the US provided such a large fiscal stimulus.

The promoters of the EMS, however, declared it a success. In the ‘Resolution of the European Council of 5 December 1978 on the Establishment of the European Monetary System (EMS) and Related matters’ (European Communities Monetary Committee, 1979: 40) it is noted that the the EMS would be a “scheme for the creation of closer monetary cooperation leading to a zone of monetary stability in Europe”. In that sense, one might concede that the objectives were attained.

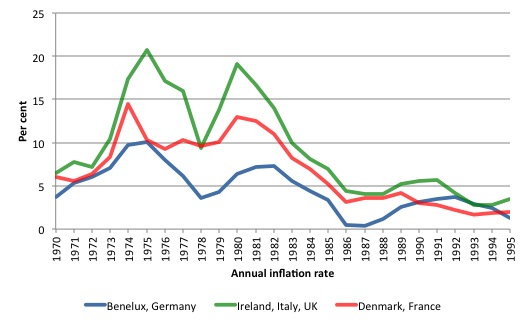

Figure 1.4 shows the evolution of annual inflation rates in the EMS member nations between 1970 and 1995. The nations are divided into the high-inflation (Ireland, Italy and the UK), medium-inflation (Denmark and France), and low-inflation (Benelux and Germany) at the inception of the EMS in March 1979. The spike in the early 1980s corresponded with the second oil price hike in 1979, which coincided with the demise of the Shah of Iran and which more than doubled. It is clear that inflation rates fell during the 1980s in all nations and convergence was nearly absolute by the mid-1980s.

Figure 1.4 Annual inflation rates, EMS member nations, 1970-1995, per cent

Source: AMECO (2014) Annual macro-economic database. Note the UK joined the EMS late in 1980 and left soon afterwards (1982).

But equating the convergence of inflation rate with economic success is only possible if the economic goals are narrowly specified. The December 5, 1978 Council Resolution also stated that the EMS should be seen “within the context of a broadly-based strategy aimed at improving the prospects of economic development” (European Communities Monetary Committee, 1979: 42) and expressed a desire to “to strengthen the economic potential of the less prosperous countries of the Community” (p.42).

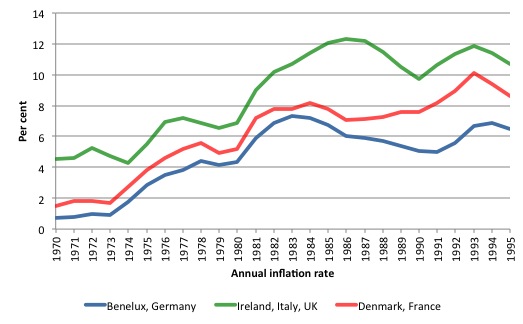

It is hard to reconcile these grand ambitions with the self-congratulatory, backslapping among the political classes that declared the EMS a success and motivated them to pave the way to Maastricht. Figure 1.5 gives a glimpse to what happened to people in Europe. Unemployment rates rose sharply in the first several years of the Monetarist economic policy onslaught and remained at elevated levels as the politicians were busy putting further nails in the coffin of European prosperity in the form of the Single European Act in February 1986, the Basel/Nyborg Agreement in September 1987, and then the 1989 Delors Report.

Baun (1996: 607) noted that the EMS produced “declining rates of economic growth in Europe throughout the 1980s” as a result of the “built-in deflationary or antigrowth bias of the system … dominated by the conservative monetary priorities of Germany and its independent central bank”. One could argue that even though the monetary union has made things more complicated, nothing fundamentally has changed in Europe today. Further, while Germany’s inflation obsession can be clothed in a philosophical argument about inflation being intrinsically anti-democratic in the sense that it is a ‘non-voted tax’, the ceding of economic sovereignty under the EMS to the Bundesbank was the beginning of the loss of democracy in Europe, which has accelerated over the course of the current crisis under the Euro. We will return to that theme in later Chapters.

So the EMS was achieving convergence – falling inflation and rising unemployment – all the nations in lock-step with Germany. How could that outcome be seen as anything desirable?

Figure 1.5 Annual unemployment rates, EMS member nations, 1970-1990, per cent

Source: see Figure 1.4.

[TO BE CONTINUED]

[WE ARE MOVING THEN TOWARDS THE DELORS REPORT IN THE LATE 1980s AND THE TREATY OF MAASTRICHT – THINGS WILL FLOW MORE QUICKLY AFTER THAT – I HOPE!]

Additional references

This list will be progressively compiled.

Bank of International Settlements (1985) Fifty-Fifth Annual Report, Basel.

Bank of International Settlements (1988) 58th Annual Report, Basel.

Baun M.J. (1996) ‘The Maastricht Treaty As High Politics: Germany, France, and European Integration’, Political Science Quarterly, 100(4), 605-624.

de Boissieu, C. and Pisani-Ferry, J. (1995) ‘The Political Economy of French Economic Policy in the Perspective of EMU’, Centre d’Etudes Prospectives et d’Informations Internationales, Document de travail n°95-09, October.

European Communities Monetary Committee (1979) ‘Resolution of the European Council of 5 December 1978 on the Establishment of the European Monetary System (EMS) and Related matters’, in Compendium of Community Monetary Texts, EEC, Brussels.

http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/emu_history/documentation/compendia/a791231en1771979compendiumcm_a.pdf

the caption in “Figure 1.5 Annual unemployment rates, EMS member nations, 1970-1990, per cent” says “Annual inflation rate”

I’m curious Bill what your thoughts/comments on the latest ruling from the German constitutional court that the EDB’s current bond purchases are illegal, and where that fits into things. It does seem that the Germans certainly see the ECB as an extension of the Bundesbank, and, though they talk piously about independance, do not actually entertain it having actual independance to do what a real central bank needs to do.

I also agree with your points on democracy, and given the way the Germans have behaved and the current ruling it certainly with the German constitution court’s ruling is certainly putting German ‘democracy’ ahead of everyone else may wish democratically, and certainly they don’t envision a central bank that is responsive to Europe as a whole.