Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

Saturday Quiz – March 29, 2014 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for yesterday’s quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of modern monetary theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

strong>Question 1:

Tax revenue provides a national government with non-inflationary spending capacity.

The answer is True.

You might consider this a trick in the sense that taxation is not required by a currency-issuing government to “fund” its spending. That is true. But that observation just raises the question as to what the purpose of taxation is in a fiat monetary system. Then you have to think a bit more deeply than the obvious … and a bit more deeply again.

In a fiat monetary system the currency has no intrinsic worth. Further the government has no intrinsic financial constraint. Once we realise that government spending is not revenue-constrained then we have to analyse the functions of taxation in a different light. The starting point of this new understanding is that taxation functions to promote offers from private individuals to government of goods and services in return for the necessary funds to extinguish the tax liabilities.

In this way, it is clear that the imposition of taxes creates unemployment (people seeking paid work) in the non-government sector and allows a transfer of real goods and services from the non-government to the government sector, which in turn, facilitates the government’s economic and social program.

The crucial point is that the funds necessary to pay the tax liabilities are provided to the non-government sector by government spending. Accordingly, government spending provides the paid work which eliminates the unemployment created by the taxes.

It is the introduction of State Money (government taxing and spending) into a non-monetary economics that raises the spectre of involuntary unemployment. Involuntary unemployment is idle labour offered for sale with no buyers at current prices (wages).

Unemployment occurs when the private sector, in aggregate, desires to earn the monetary unit of account, but doesn’t desire to spend all it earns, other things equal. As a result, involuntary inventory accumulation among sellers of goods and services translates into decreased output and employment. In this situation, nominal (or real) wage cuts per se do not clear the labour market, unless those cuts somehow eliminate the private sector desire to net save, and thereby increase spending.

The purpose of State Money is for the government to move real resources from private to public domain. It does so by first levying a tax, which creates a notional demand for its currency of issue. To obtain funds needed to pay taxes and net save, non-government agents offer real goods and services for sale in exchange for the needed units of the currency. This includes, of-course, the offer of labour by the unemployed. The obvious conclusion is that unemployment occurs when net government spending is too low to accommodate the need to pay taxes and the desire to net save.

So the point is that for a fiat currency to be used in an economy, people in the non-government sector have to have a motive to get hold of it. The imposition of a tax obligation that can only be extinguished in the fiat unit of account provides that motive.

However, the government could impose any obligation, which could only be met by people in the non-government sector by acquiring the fiat currency and returning it to the government. This is the reason

Imposing a fine for people every time they walked down the street would be one alternative to taxation to accomplish a “demand” for the particular fiat currency. Once people have to get hold of that currency they will willingly exchange goods and services in return for public spending.

The reference to non-inflationary is also important. The government could spend whenever it wanted to without the tax revenue creating the real resource space. But then, if the economy was already at full capacity such increases in nominal aggregate demand would be inflationary.

Clearly, when there is mass unemployment, taxes are already “too high” relative to the current spending. But that doesn’t negate the truth of the answer.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- A modern monetary theory lullaby

- Deficit spending 101 – Part 1

- Deficit spending 101 – Part 2

- Deficit spending 101 – Part 3

- Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 1

- Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 2

- Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 3

Question 2:

When there is an external deficit, the private sector can save overall (spend less overall than it earns) as long as the government supports saving by running a deficit.

The answer is False.

This question relies on your understanding of the sectoral balances that are derived from the national accounts and must hold by defintion. The statement of sectoral balances doesn’t tell us anything about how the economy might get into the situation depicted. Whatever behavioural forces were at play, the sectoral balances all have to sum to zero. Once you understand that, then deduction leads to the correct answer.

To refresh your memory the balances are derived as follows. The basic income-expenditure model in macroeconomics can be viewed in (at least) two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of spending; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the income produced. Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances.

From the sources perspective we write:

GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

From the uses perspective, national income (GDP) can be used for:

GDP = C + S + T

which says that GDP (income) ultimately comes back to households who consume (C), save (S) or pay taxes (T) with it once all the distributions are made.

Equating these two perspectives we get:

C + S + T = GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

So after simplification (but obeying the equation) we get the sectoral balances view of the national accounts.

(I – S) + (G – T) + (X – M) = 0

That is the three balances have to sum to zero. The sectoral balances derived are:

- The private domestic balance (I – S) – positive if in deficit, negative if in surplus.

- The fiscal Deficit (G – T) – negative if in surplus, positive if in deficit.

- The Current Account balance (X – M) – positive if in surplus, negative if in deficit.

These balances are usually expressed as a per cent of GDP but that doesn’t alter the accounting rules that they sum to zero, it just means the balance to GDP ratios sum to zero.

A simplification is to add (I – S) + (X – M) and call it the non-government sector. Then you get the basic result that the government balance equals exactly $-for-$ (absolutely or as a per cent of GDP) the non-government balance (the sum of the private domestic and external balances).

This is also a basic rule derived from the national accounts and has to apply at all times.

To help us answer the specific question posed, we can identify three states all involving public and external deficits:

- Case A: Fiscal Deficit (G – T) < Current Account balance (X - M) deficit.

- Case B: fiscal Deficit (G – T) = Current Account balance (X – M) deficit.

- Case C: fiscal Deficit (G – T) > Current Account balance (X – M) deficit.

For the private sector reduce it overall indebtedness (that is a net result) it must spend less than it earns – that is, run a surplus. So we understand the question to be examining the conditions under which the private domestic sector can run a surplus when the external sector is in deficit.

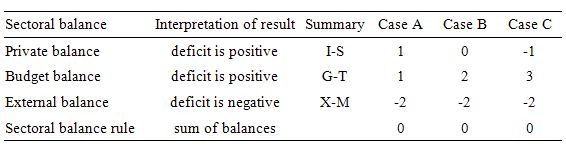

The following Table shows three cases expressing the sectoral balances as percentages of GDP in each case there is an external deficit. So the constant external deficit then allows you to understand the relationship between the other two balances – government and private domestic.

In Cases A and B, the private balance is in deficit or balanced which means that no net debt repayments could occur even though the government sector is in deficit.

In Case C, we see that the deficit has risen to 3 per cent of GDP and larger than the external deficit as a percent of GDP (2 per cent). At that point, the private sector balance goes into surplus which facilitates reductions in debt levels overall.

So the coexistence of a fiscal deficit (adding to aggregate demand) and an external deficit (draining aggregate demand) does not necessarily lead to the private domestic sector being in surplus.

It is only when the fiscal deficit is large enough (3 per cent of GDP) and able to offset the demand-draining external deficit (2 per cent of GDP) that the private domestic sector can save overall (Case C).

The economics lying behind the accounting statements (which are true by definition) is that the fiscal deficits underpin spending and allow income growth to be sufficient to generate savings greater than investment in the private domestic sector.

But they can only do that as long as they can offset the demand-draining impacts of the external deficits and thus provide sufficient income growth for the private domestic sector to save.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Stock-flow consistent macro models

- Norway and sectoral balances

- The OECD is at it again!

- Saturday Quiz – May 22, 2010 – answers and discussion

Question 3:

When a sovereign government issues debt to match its fiscal deficit, the financial wealth of the non-government increases.

The answer is False.

The fundamental principles that arise in a fiat monetary system are as follows.

- The central bank sets the short-term interest rate based on its policy aspirations.

- Government spending is independent of borrowing and the latter best thought of as coming after spending.

- Government spending provides the net financial assets (bank reserves) which ultimately represent the funds used by the non-government agents to purchase the debt.

- fiscal deficits that are not accompanied by corresponding monetary operations (debt-issuance) put downward pressure on interest rates contrary to the myths that appear in macroeconomic textbooks about ‘crowding out’.

- The “penalty for not borrowing” is that the interest rate will fall to the bottom of the “corridor” prevailing in the country which may be zero if the central bank does not offer a return on reserves.

- Government debt-issuance is a “monetary policy” operation rather than being intrinsic to fiscal policy, although in a modern monetary paradigm the distinctions between monetary and fiscal policy as traditionally defined are moot.

National governments have cash operating accounts with their central bank. The specific arrangements vary by country but the principle remains the same. When the government spends it debits these accounts and credits various bank accounts within the commercial banking system. Deposits thus show up in a number of commercial banks as a reflection of the spending. It may issue a cheque and post it to someone in the private sector whereupon that person will deposit the cheque at their bank. It is the same effect as if it had have all been done electronically.

All federal spending happens like this. You will note that:

- Governments do not spend by “printing money”. They spend by creating deposits in the private banking system. Clearly, some currency is in circulation which is “printed” but that is a separate process from the daily spending and taxing flows.

- There has been no mention of where they get the credits and debits come from! The short answer is that the spending comes from no-where but we will have to wait for another blog soon to fully understand that. Suffice to say that the Federal government, as the monopoly issuer of its own currency is not revenue-constrained. This means it does not have to “finance” its spending unlike a household, which uses the fiat currency.

- Any coincident issuing of government debt (bonds) has nothing to do with “financing” the government spending.

All the commercial banks maintain reserve accounts with the central bank within their system. These accounts permit reserves to be managed and allows the clearing system to operate smoothly. The rules that operate on these accounts in different countries vary (that is, some nations have minimum reserves others do not etc). For financial stability, these reserve accounts always have to have positive balances at the end of each day, although during the day a particular bank might be in surplus or deficit, depending on the pattern of the cash inflows and outflows. There is no reason to assume that these flows will exactly offset themselves for any particular bank at any particular time.

The central bank conducts “operations” to manage the liquidity in the banking system such that short-term interest rates match the official target – which defines the current monetary policy stance. The central bank may: (a) Intervene into the interbank (overnight) money market to manage the daily supply of and demand for reserve funds; (b) buy certain financial assets at discounted rates from commercial banks; and (c) impose penal lending rates on banks who require urgent funds, In practice, most of the liquidity management is achieved through (a). That being said, central bank operations function to offset operating factors in the system by altering the composition of reserves, cash, and securities, and do not alter net financial assets of the non-government sectors.

Fiscal policy impacts on bank reserves – government spending (G) adds to reserves and taxes (T) drains them. So on any particular day, if G > T (a fiscal deficit) then reserves are rising overall. Any particular bank might be short of reserves but overall the sum of the bank reserves are in excess. It is in the commercial banks interests to try to eliminate any unneeded reserves each night given they usually earn a non-competitive return. Surplus banks will try to loan their excess reserves on the Interbank market. Some deficit banks will clearly be interested in these loans to shore up their position and avoid going to the discount window that the central bank offeres and which is more expensive.

The upshot, however, is that the competition between the surplus banks to shed their excess reserves drives the short-term interest rate down. These transactions net to zero (a equal liability and asset are created each time) and so non-government banking system cannot by itself (conducting horizontal transactions between commercial banks – that is, borrowing and lending on the interbank market) eliminate a system-wide excess of reserves that the fiscal deficit created.

What is needed is a vertical transaction – that is, an interaction between the government and non-government sector. So bond sales can drain reserves by offering the banks an attractive interest-bearing security (government debt) which it can purchase to eliminate its excess reserves.

However, the vertical transaction just offers portfolio choice for the non-government sector rather than changing the holding of financial assets.

So debt-issuance does not increase the assets that are held by the non-government sector $-for-$” nor does it reduce the capacity of the private sector to borrow from banks because they use their deposits to buy the bonds (crowding out).

The latter crowding out myth is based on the erroneous belief that the banks need deposits and reserves before they can lend. Mainstream macroeconomics wrongly asserts that banks only lend if they have prior reserves. The illusion is that a bank is an institution that accepts deposits to build up reserves and then on-lends them at a margin to make money. The conceptualisation suggests that if it doesn’t have adequate reserves then it cannot lend. So the presupposition is that by adding to bank reserves, quantitative easing will help lending.

But this is an incorrect depiction of how banks operate. Bank lending is not “reserve constrained”. Banks lend to any credit worthy customer they can find and then worry about their reserve positions afterwards. If they are short of reserves (their reserve accounts have to be in positive balance each day and in some countries central banks require certain ratios to be maintained) then they borrow from each other in the interbank market or, ultimately, they will borrow from the central bank through the so-called discount window. They are reluctant to use the latter facility because it carries a penalty (higher interest cost).

The point is that building bank reserves will not increase the bank’s capacity to lend. Loans create deposits which generate reserves.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Quantitative easing 101

- Building bank reserves will not expand credit

- Building bank reserves is not inflationary

- Money multiplier and other myths

- Will we really pay higher interest rates?

- A modern monetary theory lullaby

That is enough for today!

This Post Has 0 Comments