Today (March 6, 2024), the Australian Bureau of Statistics released the latest - Australian National…

Australian national accounts – weak and getting weaker

When the first-quarter National Accounts data came out for Australia I noted that despite the relatively strong growth recorded in that period, the Australian economy was in a fragile state and the contemporary indicators (given that the real GDP data is 3 months old by the time it is published) were indicating that the economy would slow significantly in the June-quarter. Today’s Australian Bureau of Statistics – Australian National Accounts – for the June-quarter 2014, confirms that prediction. Real GDP growth grew by 0.5 per cent down from 1.1 per cent in the June-quarter 2013. The annualised growth rate of 3.1 per cent is being held up by the strong June-quarter growth but something around 2 per cent per annum looking forward is a more realistic assessment of where the economy is at present. The external sector is now a negative influence on growth as is the government sector. In this quarter, there was a large inventory adjustment (up) which was the difference between positive and negative growth overall. That short of inventory swing will not continue. With export prices plummetting due to a glut in iron ore shipments to China, the external sector will continue to be a drag. Fiscal austerity is set to worse, which means that the data paints a fairly gloomy picture for the Australian economy for the rest of this year at least.

The main features of the National Accounts release for the June-quarter 2014 were (seasonally adjusted):

- Real GDP increased by 0.5 per cent after recording a 1.1 per cent increase in the March-quarter.

- The main positive contributors to expenditure were Changes in inventories (0.9 percentage points), Final consumption expenditure (0.3 percentage points) and Private gross fixed capital formation (0.3 percentage points).

- The main negative factors were Net exports (-0.9 percentage points) and Public gross fixed capital formation (-0.2 percentage points).

- Our Terms of Trade (seasonally adjusted) fell dramatically by 4.1 per cent in the quarter and over the last 12 months they have fallen by a substantial 7.9 per cent. So, the hoped for second-phase of the Mining boom after the initial building of infrastructure is not happening – export volumes are up but prices are well down.

- Real net national disposable income, which is a broader measure of change in national economic well-being fell by 0.2 per cent for the quarter but rose by 1 per cent for the 12 months to the June-quarter 2014, which means that Australians are better off (on average than in 2013) but that well-being is now being eroded.

Overall growth picture – tepid and cooling

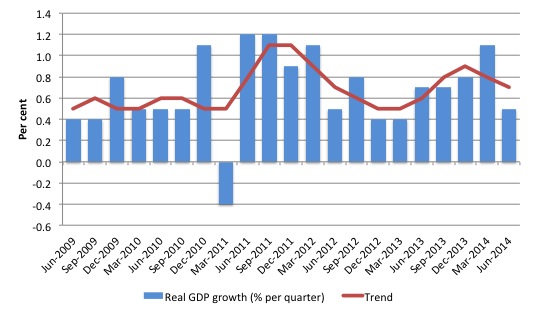

The following graph shows the quarterly percentage growth in real GDP over the last five years to the June-quarter 2014 (blue columns) and the ABS trend series (red line) superimposed. After the decline in trend growth was arrested by the fiscal stimulus in 2008-09 the decline in government support saw the dip in trend growth in 2010.

Initially, the growth in private investment associated with the record terms of trade and the resulting mining boom helped drive the new rise in trend growth and that appears to have ended towards the end of 2013, notwithstanding the strong net exports in the March-quarter 2014.

The mining boom was thought to be in two stages. First, the investment boom as new productive infrastructure was being constructed (railways, ports, loaders, new sites etc). Second, the export boom that would result from the enlarged productive capacity. TIf the net exports continue to be strong then the trend will likely rise again but that is a big if at this stage. The second stage relies on continued growth in China to boost volumes and the prices remaining stable (at elevated levels).

The problem is that China is likely to slow a little but more troubling for the economy as a whole is that there is now a serious glut of mineral exports in China (iron ore etc) and the excess supply is driving prices down fast.

Further, while the fiscal austerity built into the May 2014 Budget Statement is not going to impact heavily this financial year, there is still some drag coming from the public cutbacks as evidenced by the negative contribution of for public capital formation.

Consumer confidence is also weak as a result of the announcements by the government of cutbacks and that will contain any growth in household consumption.

Of importance is the fact that without the big bounce back in inventory growth in the June-quarter, Australia would have been heading for recession. That contribution (see below) is not likely to sustain itself next quarter and so the future outlook is weak.

The fragility of the growth path arises because there is no real signs of growth in any sector other than mining, and clearly net exports are now dragging on economic growth.

Contributions to growth

What components of expenditure added to and subtracted from real GDP growth in the June-quarter 2014?

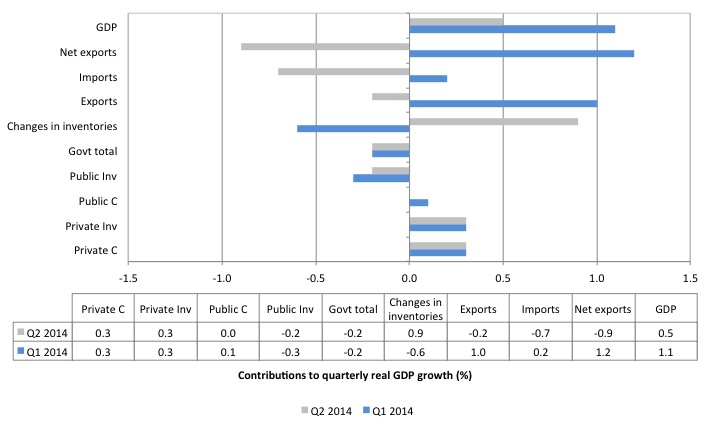

The following bar graph shows the contributions to real GDP growth (in percentage points) for the main expenditure categories. It compares the June-quarter 2014 contributions (grey bars) with the March-quarter 2014 (blue bars).

The staggering result is that the massive swing in the net exports contribution to growth as the terms of trade have fallen sharply.

The overall contribution of private investment was a modest 0.2 percentage points and confirms that the investment cycle associated with the mining boom is over.

There was a further sharp contraction in public investment, which continues to drag growth down (-0.2 percentage points). There is no contribution coming from public consumption spending. Thus the overall contribution of the government to growth is negative (-0.2 percentage points). Fiscal austerity is thus damaging growth and helping to drive up unemployment.

The contribution of Private consumption is moderate and flat.

As noted above, the only reason the economy exhibited positve (though modest) growth was due to the positive inventory contribution, which will not be sustained.

The overall assessment is that the Australian economy is now growing well below trend and with terms of trade expected to fall further and the fiscal position expected to become tighter, the outlook is for weaker growth still.

This is especially so given the contributions from private domestic expenditure are very modest indeed as households maintain their cautious approach and the relatively high saving ratio and investment flattens out and the increasing fiscal drag coming from the public sector.

Last quarter I wrote “I predict that the contributions from net exports will be much lower in the June-quarter data” – which turned out to be true – although the extent to which the external sector is now dragging on growth is greater than anyone thought.

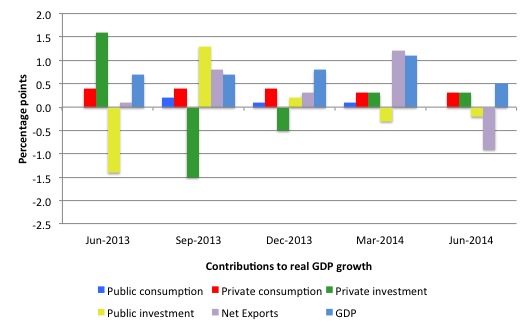

The next graph shows the contributions to real GDP growth of the major expenditure aggregates since June-quarter 2013 (in percentage points). The total real GDP growth (in per cent) is also included as a reference.

The stand-out result is the dominance of net exports and the subdued behaviour of the other expenditure components. As noted above, real GDP growth in Australia is now delicately poised.

Wage share rises a little

The wage share in national income rose in the June-quarter to 53.5 per cent, up by 0.5 percentage points. It has fallen by 0.5 percentage points in the last year.

The following graph shows the movement in GDP per hour worked and the Average Real Wage per worker in index number form from June-quarter 1980 to the current quarter.

Productivity growth was 2.8 per cent over the last 12 months, whereas real wages grew by only 1.4 per cent. In the current quarter, real wages growth was zero.

The widening gap indicates that capital (profits) have been gaining an increasing share of real GDP (national income) at the expense of the workers. imilar trends have been reported in other advanced OECD nations.

While neo-liberal commentators claim this is due to globalisation, the reality is that it has been driven by attacks on trade unions, increased casualisation and persistently high unemployment and underemployment. These factors have combined to make it difficult for workers to gain real wages growth. Globalisation is only one part of the story.

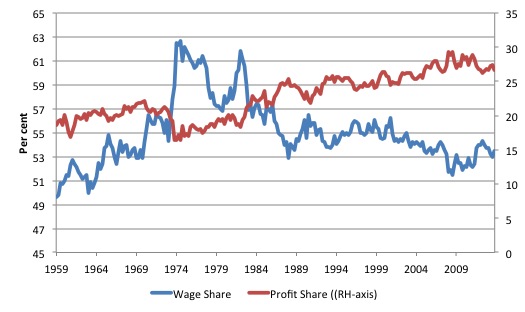

The next graph shows the outcomes in terms of movements in the wage share in national income (%) and the profit share (%) from the September-quarter 1959 to the current quarter.

As I have noted in the past, the deregulation in the labour markets not only increased job instability and created persistently high unemployment, but also led to large shifts in national income from wages to profits. Similar trends have been reported in other advanced OECD nations.

First, in most nations, the wage share in national income has fallen significantly over the past 35 years. Second, in the Anglo nations, ‘a sharp polarisation of personal income distribution has occurred’, with the top percentile and decile of the personal income distribution substantially increasing their total shares. The excessive executive pay deals that emerged in this period were one manifestation of the munificence gained at the expense of lower income workers.

Until the early 1980s, real wages and labour productivity typically moved together. However, as the attacks on the capacity of workers to secure wage increases intensified, a gap between wages and productivity opened and widened. This widening gap manifested as a rising profit share: in 1975, the Australian wage share was around 62.5 per cent of national income to be distributed to the factors of production. In the current-quarter it was around 54 per cent.

Australian governments aided this redistribution in a number of ways, through privatisation, outsourcing, harsh industrial relations legislation aimed at reducing union power, National Competition Policy and so on.

These movements in national income shares are also tied into the financial crisis. Imbued with the now-discredited ‘efficient markets’ hypothesis promoted by the University of Chicago economists, policy makers bowed to pressures from the financial sector.

They introduced widespread financial deregulation and reduced their oversight of the banking sector. This led to a massive expansion of the financial sector, and also set the stage for the transformation of banks from safe deposit havens to global speculators carrying increasing (and ultimately unknown) risks. The massive redistribution of the balance between national income and profits provided the banks and hedge funds with the gambling chips to fuel the rapid expansion of the ‘global financial casino’.

The capitalist dilemma was that real wages typically had to grow in line with productivity, to ensure that the goods produced were sold. So how does economic growth sustain itself when labour productivity growth outstrips the growth in the real wage? This was particularly significant in the context of the increasing fiscal drag coming from public surpluses, which squeezed private purchasing power in many nations during the 1990s and beyond.

The neoliberal period found a new way to solve the dilemma. The ‘solution’ was so-called ‘financial engineering’, which pushed ever-increasing debt onto households and firms. The credit expansion sustained the workers’ purchasing power, but also delivered an interest bonus to capital, while real wages growth continued to be suppressed. Households, in particular, were enticed by lower interest rates and the vehement marketing strategies of the financial engineers. It seemed too good to be true and it was.

The result was that Australian households now hold record levels of debt. The debt to disposable income ratio stood at 69.1 per cent in March 1996; by December 2013, it had risen to a staggering 148.8 per cent.

Governments, their central banks and so-called financial industry experts played down any sense of alarm during the pre-crisis period, claiming that wealth was growing along with the debt. When the debt bubble burst, significant proportions of the ‘wealth’ vanished, leaving many borrowers with massive debts but few assets.

To restore a sustainable growth footing, there has to be a dramatic shift in the distribution of national income – towards workers. Real wages have to grow more or less in line with productivity, which will require legislative changes and higher government spending to reduce unemployment so there is more pressure on firms to pass on the productivity gains.

Household saving ratio rises to 9.4 per cent

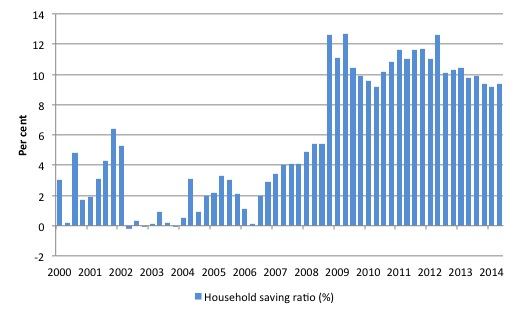

The following graph shows the household saving ratio (% of disposable income) from 2000 to the current period. The household sector is now behaving very differently since the GFC rendered its balance sheet very precarious. Prior to the crisis, households maintained very robust spending (including housing) by accumulating record levels of debt. As the crisis hit, it was only because the central bank reduced interest rates quickly, that there were not mass bankruptcies.

The household saving ratio was 9.4 per cent of disposable household income in the June-quarter 2014 and slightly up on the 9.2 per cent in the previous quarter. There is no apparent move for households to reduce this level of saving and consumption growth remains modest.

For the economy to continue to grow strongly while households are maintaining this higher level of saving (from disposable income), public spending, private investment and/or net exports have to increase.

As noted above, net exports is now providing a drag on growth. Private investment also remains weak given the modest outlook.

The household sector is now carrying record levels of debt as a result of the credit binge leading up to the crisis and we are unlikely to see a return to the low saving ratios that were evident in the period 2000 to 2005.

That means that government surpluses which were associated with the credit binge, and only were made possible by the unsustainable credit binge are untenable in this new (old) climate. The Government needs to learn about these macroeconomic connections. It will learn the hard way once net exports weakens.

Real GDP growth and hours worked

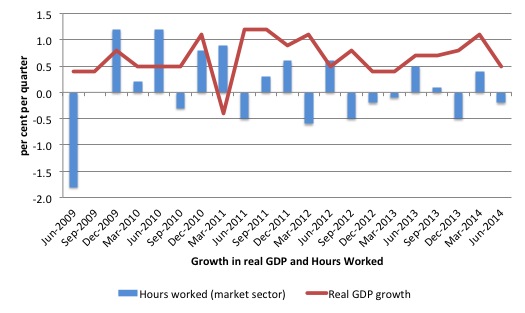

One of the puzzles over the last several years or so has been the sharp dislocation between what is happening in the labour market and what the National Accounts data has been telling us.

Employment growth and hours worked has been virtually flat over the period while annual real GDP growth has been around 2.4 to 2.6 per cent. Today’s data shows that real GDP growth has fallen on the back of sustained higher productivity growth and decreased hours of work.

The rising productivity growth and the mostly below-trend real GDP growth has helped to explain why employment growth has been unusually flat over the last 24 months.

The following graph presents quarterly growth rates in trend GDP and hours worked using the National Accounts data for the last five years to the June-quarter 2014.

You can see the major dislocation between the two measures that appeared in the middle of 2011 persisted throughout 2013. While hours worked increased in the middle two quarters of 2013 and were more in line with what we would expect, the divergence between real output growth and hours worked has once again widened.

Just in case you think the labour force data is suspect, the hours worked computed from that data is very similar to that computed from the National Accounts.

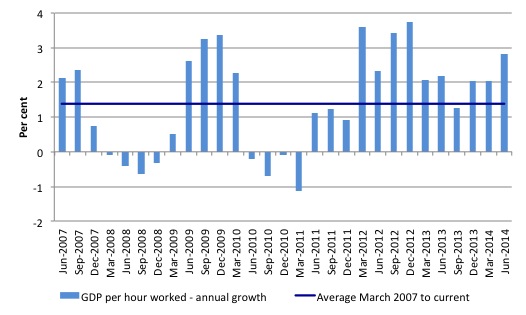

To see the above graph from a different perspective, the next graph shows the annual growth in GDP per hour worked (so a measure of labour productivity) from the March 2007 quarter to the June-quarter 2014. The horizontal blue line is the average annual growth since March 2007.

The relatively strong growth in labour productivity in 2012 and the mostly above average growth in 2013 and 2014 helps explain why employment growth has been lagging given the real GDP growth. Growth in labour productivity means that for each output level less labour is required.

Labour productivity growth has accelerated over the last three quarters, which is why jobs growth is so modest (and zig-zagging around the negative line).

Conclusion

Today’s National Accounts data indicates that economic growth is slowing and well below trend. The extraordinary growth in net exports that had driven growth in previous quarters was never going to last and the external sector is now dragging growth down.

With negative real wages growth and rising productivity, the wage share continues to languish and the record levels of household debt will continue to constrain household consumption.

The government sector is also draining growth now and causing unemployment to rise. Unless there is a dramatic shift in government sentiment, their role in the economy will continue to be negative.

With demand fairly flat there is little incentive for private firms to increase the investment ratio.

Remember that the National Accounts tells us what was happening in 3-6 months ago. The most recent evidence is mixed but we know that export prices continue to fall and China continues to slow. Both of those facts would suggest that today’s data is a reasonable projection of the future.

That is why I deem the situation fairly fragile at present.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2014 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

You know, Bill, reading all your useful summaries of already published data … one can’t help recognizing how droll this all is.

The so-called “Business Cycle” – and bubbles/booms/busts/Bull-Mkts & Depressions too – are simply the result of old/young buffoons failing to network adequately.

When distributed components of a SYSTEM quit sending/receiving/analyzing/test-responding to enough of their own distributed feedback …. well, then their systems break down. The insane return-on-coordination rapidly declines, as an inevitable result.

That core reason WHY cultural systems get too far from unpredictable Cultural Survival Paths is the same old story throughout the history of planet Earth. The real message is that if WE don’t evolve a BETTER WAY – ASAP – to manage our own affairs, then some other system WILL quickly replace us, as sure as the sun rises.

Any combination of young-to-old buffoons can quickly run whole cultures off a cliff, or linger too long in the past, long past when context has changed – IF THE WRONG PEOPLE ARE HANDED THE POLICY REINS!!!

We can talk and argue endlessly about all the details of all the late, expensive repairs to degraded systems (call them various ideologies) … but the approach that will win in the end is to raise citizens who first gain, early on, an appreciation for systems, and then NEVER LOSE IT!

Every other approach is a losing strategy. No organically growing system can keep up with expensive repair alone. Only cheap prevention works. We won’t recover until this message results in very systemic overhaul of K-12 edu. Until then, we’ll keep churning out a majority who are some data late and a context short of national return-on-coordination.

A Group Intelligence is a terrible thing to waste, but we’re trying our best to do it.

Its pretty much the same story in the UK too. The problem is that politicians think they are improving things but a misunderstanding (lets be kind and assume that) prevents them from making any progress.

I’ve been trying unsuccessfully to explain to John Redwod (UK ex government minister on the Right of the Tory party) that, even if the deficit is really as bad as he thinks it is, the government is never going to reduce it simply by raising taxes and reducing spending.

The good things about John Redwood , IMO, are that he’s a Eurosceptic but also he’s never censored my posts even though I’m always disagreeing with him! He’s even sent me a couple of friendly emails.

He does seem to have noticed that tax revenues don’t do quite what he wants. He’s obviously an intelligent person so I’m still optimistic that the penny will drop with him one day!

http://johnredwoodsdiary.com/2014/09/03/higher-rates-less-revenue-the-agony-of-uk-finances/#comment-656126

Being a devotee of Schadenfreude I would love to see Growth Addicts Inc. eat crow.

They have struck a Faustian bargain with the Devil. Guess who wins.

This will not become an issue until the top end of towns slice of the pie starts to decrease.

As long as productivity increases faster than wages – the share of income going to the capitalist will increase and the share going to wages will decline.

Hence, as far as government is concerned – as long as the puppet master is happy there is no problem.

A strangely backhanded comment on this article from Greg Jericho in The Guardian, ” It wouldn’t be a naitonal accounts if Bill Mitchell wasn’t a bit negative about them! But he’s often worth a read. His posts are bit more economic heavy, but if that’s you thing, have read here”

His post are a bit more economic heavy??? But isn’t that what we are discussing. Dismissing Bill’s work as heavy seems to miss the point. How is unemployment going, Greg. How is youth unemployment going?

It is pretty simple unless unemployment is falling even with labour force growth or at the very least staying level (not that I recommend that), the economy is faltering.

With other nations in a similar state and apparent refusal to recognise the abilities they have with actual economic operations to fix it, along with International crises, it wouldn’t be surprising to see another World War or an isolated war in the crisis affected areas that amalgamate into a bigger war in those areas.

Now I’m not saying that will/would happen but if it does, it would not be a surprise.

Sad thing is, most of it can be fixed by pulling the economic levers the authorities refuse to pull.

Having read Mr Jericho’s article after this one, I would call it economic heavy as well.