It was only a matter of time I suppose but the IMF is now focusing…

European Youth Guarantee audit exposes its (austerity) flaws

On Tuesday (March 24, 2015), the European Court of Auditors, which is the EU’s independent external auditor and aims to improve “EU financial management”, released a major report – EU Youth Guarantee: first steps taken but implementation risks ahead (3 mb). The Report reflects on the experience of the program which was introduced in April 2013. When the European Commission proposed the initiative I wrote that it was underfunded, poorly focused (on supply rather than demand – that is, job creation) and would fail within an overwhelming austerity environment. The Audit Report is more diplomatic as you would expect but comes up with findings that are not inconsistent with my initial assessment in 2012.

As an aside, the European Court of Auditors was not that long ago mired in allegations that it knowingly swept “abuse of EU funds … under the carpet” (Source).

Evidently, the European Groupthink permeated this body and the then head pressured auditors to “tone down findings of abuse”.

Facts

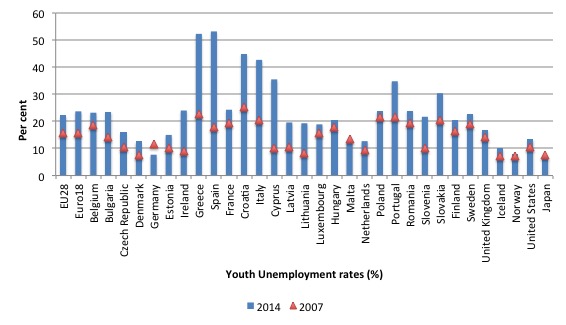

The following graph shows the youth (15-24 years) unemployment rates in 2007 (cerise triangles) and 2014 (blue bars) for the range of nations that Eurostat supplies comparative data for.

In several nations the increase in youth unemployment and the persistence of the high rates has been significant.

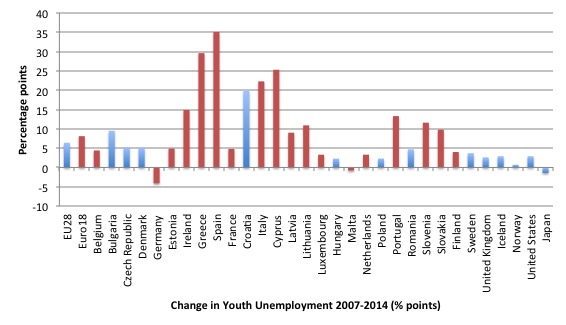

The next graph shows the change in youth unemployment rates between 2007 and 2011. The cerise bars are the Euro nations (minus Austria for which no 2014 data is available from Eurostat).

It is clear that the Eurozone nations have fared worse in this regard relative to the other nations in the Eurostat sample.

The average change in youth unemployment rates between 2007 and 2014 was 11.9 percentage points. For non-Euro nations which Eurostat provides data for by way of comparison (Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Denmark, Croatia, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Sweden, UK, Iceland, Norway, US and Japan), the average change in youth unemployment rates between 2007 and 2014 was 4.6 percentage points.

The reason for that difference lies mainly in the conduct of fiscal policy (deficits kept higher for longer) and earlier and stronger returns to growth (with exceptions).

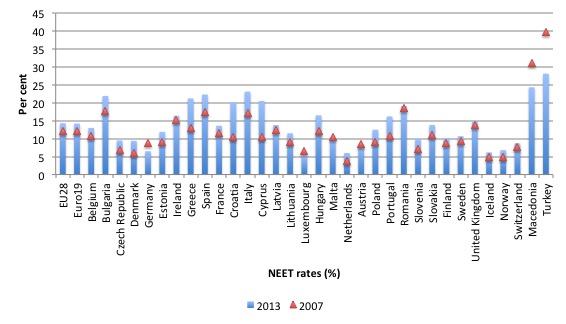

Furthermore, the data for the – NEET – generation (youth who are Not in Education, Employment or Training) is damning.

The following graph shows the NEET rates for 2007 (triangles) and 2013 (bars) for a range of countries that Eurostat publishes this data for.

This data led the former European Commission President Barroso to claim in early 2013 that Europe faced a “genuine social emergency” because the “social situation is very severe. Unemployment, in particular youth unemployment is a huge concern for all of us. In 12 of our 27 member states youth unemployment is higher than 25 percent.” (Source).

It was of course a social emergency that Barroso and his fellow political leaders had created themselves by their insistence on choking economic growth in the name of meeting largely irrelevant fiscal parameters.

When the European Commission announced their intention to introduce a Youth Guarantee scheme, the relevant European Commission Commissioner László Andor we released a press briefing which said:

High youth unemployment has dramatic consequences for our economies, our societies and above all for young people. This is why we have to invest in Europe’s young people now … This Package would help Member States to ensure young people’s successful transition into work. The costs of not doing so would be catastrophic.

The costs “would be catastrophic”, which indicates to me – as a native English speaker – that this is a situation of the highest emergency and requires a response that would be commensurate with such an impending catastrophe.

The European Court of Auditors summarised the resulting Youth Guarantee in this way:

Under the Youth Guarantee Member States should ensure that, within four months of leaving school or losing a job, young people under the age of 25 can either find a “good-quality” job suited to their education, skills and experience or acquire the education, skills and experience required to find a job in the future through an apprenticeship, a traineeship or continued education.

The European group – Eurofound (European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions), which was established in 1975 as “a European Union body … to contribute to the planning and design of better living and working conditions in Europe”, published a report (October 22, 2012) – Young people not in employment, education or training: Characteristics, costs and policy responses in Europe – which, in part, tried to estimate the costs of not integrating the NEETs (youth that are not in employment, education or training).

In summary, the Eurofound Report concluded that:

Despite being conservative, the estimated loss due to the labour market disengagement of young people is substantial. In 2008, the 26 Member States lost almost €120 billion, corresponding to almost 1% of European GDP. When the recent economic crisis and the increase in the NEET population between 2008 and 2011 is taken into account, it is likely that this loss has been even greater … It was estimated to be €153 billion, corresponding to more than 1.2% of GDP in Europe. While this cost varies a great deal between Member States, a considerable deterioration of the situation was observed in Bulgaria, Cyprus, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia and Poland. In all these countries, the loss in 2011 due to the disengagement of young people from the labour market was equal to 2% or more of each country’s GDP.

For example, for Greece the estimated losses are €7,065,609,793 or 3.28 per cent of GDP in 2011 (1.74 per cent of GDP in 2008).

So a large scale economic as well as a human catastrophe.

My earlier comments on the Youth Guarantee

However, the response that the European Commission made in the form of the Youth Guarantee did not signal that they thought it was that much of a catastrophe.

I wrote an initial appraisal of the EUs Youth Guarantee plan in this blog – Youth Guarantee has to be a Youth Job Guarantee.

More recently, after some new data had come in I wrote a blog – Public employment and other matters of scale.

The initial criticism related to the scope envisaged by the scheme and the funding promises that were made.

The European Commission’s Youth Guarantee is more of an elaborate supply-side activation scheme than a job creation initiative, which makes it part of the problem and cannot be part of the solution.

The “measures” proposed by the European Commission’s Youth Guarantee (and my annotations) are as follows:

- “Outreach strategies and focal points” – promotion of policy initiatives, training, information

- “Provide individual action planning” – training

- “Offer early school leavers and low-skilled young people routes to re-enter education and training or second-chance education programmes, address skills mismatches and improve digital skills” – training.

- “Encourage schools and employment services to promote and provide continued guidance on entrepreneurship and self-employment for young people” – training, entrepreneurship orientation.

- “Use targeted and well-designed wage and recruitment subsidies to encourage employers to provide young people with an apprenticeship or a job placement, and particularly for those furthest from the labour market” – wage subsidies.

- “Promote employment/labour mobility by making young people aware of job offers, traineeships and apprenticeships and available support in different areas and provide adequate support for those who have moved” – training and information.

- “Ensure greater availability of start-up support services” – training, information and self-employment support

- “Enhance mechanisms for supporting young people who drop out from activation schemes and no longer access benefits” – information and mentoring

- “Monitor and evaluate all actions and programmes contributing towards a Youth Guarantee, so that more evidence-based policies and interventions can be developed on the basis of what works, where and why” – evaluation

- “Promote mutual learning activities at national, regional and local level between all parties fighting youth unemployment in order to improve design and delivery of future Youth Guarantee schemes” – talk fests.

- “Strengthen the capacities of all stakeholders, including the relevant employment services, involved in designing, implementing and evaluating Youth Guarantee schemes, in order to eliminate any internal and external obstacles related to policy and to the way these schemes are developed” – training and talk fest

So the Youth Guarantee looked like it was biased towards supply-side measures.

This “activation” emphasis has defined OECD policy since the release of the Jobs Study in 1994. The OECD advocated extensive supply-side reform with a particular focus on the labour market, because supply side rigidities were alleged to inhibit the capacity of economies to adjust, innovate and be creative. The proposed reform agenda was variously adopted by many governments.

It was introduced as monetary authorities increasingly adopted inflation targeting (formal and informal) which their policy on price level targets and used unemployment as the instrument to achieve these targets.

It also was accompanied by growing fiscal conservatism, which in Europe has been expressed in the Maastricht Criteria and the Stability and Growth Pact.

The topic is covered in great detail in our 2008 book – Full Employment abandoned.

The OECD Jobs Study sought to promote the idea that there is a formal link between unemployment persistence, on one hand and so-called “negative dependence duration” and long-term unemployment, on the other hand.

Although negative dependence duration (which suggests that the long-term unemployed exhibit a lower re-employment probability than short-term jobless) is frequently asserted as an explanation for persistently high levels of unemployment, no formal link that is credible has ever been established.

The OECD constantly pressured governments to abandon the hard-won labour protections which provide job security and fair pay and working conditions for citizens.

Their solution? Cut benefits, toughen activity tests, eliminate trade union influence, abandon minimum wages and reduce any subsidies that prolong the search propensity by workers.

The result? Even before the crisis, unemployment remained well above the full employment levels in most nations; real GDP growth was muted relative to the past; real wages growth has been suppressed relative to productivity growth – leading to a massive redistribution of real income to profits; private gross capital formation has been lower than in the past.

The summary of the proposed “Youth Guarantee” measures is:

1. More training which is ineffective if it is outside the paid-work environment.

2. More information to be provided about jobs yet it is hard to provide information about jobs that are not there!

3. Proposals to address poor signalling which amounts to making one’s CV look better for jobs that are not there!).

4. Wage subsidies to address slow job growth barriers: of all the measures proposed this is the only one that seems to focus on the demand-side of the labour market.

That is, directly address the shortage of jobs. Wage subsidies have a long record of failure and operate on the flawed assumption that mass unemployment is the result of excessive wages.

There is no consistent evidence that supports the idea that private firms will provide millions of jobs to the European youth as a result of wage subsidies (100 per cent or otherwise).

If firms cannot sell the extra output they will not hire extra workers. They may hire youth and sack adults and pocket the cost differential if productivity considerations allowed.

The overwhelming problem that I see with the Youth Guarantee proposal is that it seems to skirt around the main issue – a lack of jobs. It seems to be about full employability rather than full employment.

What is needed in Europe is a large-scale job creation program for those who are not in formal education or formal apprenticeship programs. Within that job creation program, various training ladders can be included where appropriate and where the participant desires lie.

But the essential starting point in resolving the catastrophic youth unemployment crisis in Europe is not more “supply-side” activation. The problem is overwhelmingly a demand-side one – a lack of jobs. That is where the bulk of the policy intervention should be focused and now.

More recently, the European Commission (via the Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion Commission) announced that the – Youth Guarantee: Commission reviews 18 pilot projects, which reported on the progress of the scheme in the first 19 months of operation.

The press release was broadly reported, tweeted, and generally propagated through the social media as if it was a major achievement.

The European Commission had only allocated the sum of 6 billion euros to the Youth Guarantee which was a pittance.

Please read my blog – Public employment and other matters of scale – for more discussion on the progress.

The conclusion was that the 18 Youth Guarantee projects so far have produced hardly any jobs at all. Lots of talk but little action.

The Audit Report

The Report from the European Court of Auditors (ECA) is consistent with my concerns. It is not particularly encouraging given the scale of the problem that Europe is facing with its youth.

It frames the problem:

The situation is critical in some Member States where the unemployment rates affect between one in two or one in three young people, raising the prospect of a lost generation with significant socio-economic costs.

The ECA task was to assess:

… whether the Commission has provided appropriate support to Member States in setting up their Youth Guarantee schemes and reviewed possible implementation risks.

The conclusion was that the risks were high:

1. The inadequacy of the funding.

2. The quality of the activities (jobs, traineeships and apprenticeships) is questionable.

3. The monitoring and reporting of the program is at risk.

The ECA found the funding model to be problematic.

Essentially, the program would be funded in three ways: Member State contributions (within the strict Stability and Growth Pact rules), the European Social Fund (ESF) and the European Commission’s Youth Employment Initiative (YEI). The ESF is the largest contributor.

The ECA found that the program would ‘cost’ much more than originally conceived and it was not clear on the final employment outcomes.

The European Commission estimated that the total funding required to run the program between 2014 and 2020 would be 12.7 billion euro.

This would be supplemented with national and private funding of up to 4 billion euros.

The ECA write that:

This total of 16.7 billion euro amounts to around 2.4 billion euro per year.

But these estimates are ridiculous when confronted with the scale of the problem.

The ECA cites a 2012 ILO report (ILO, Global Employment Outlook, “Global spill-overs from advanced to emerging economies worsen the situation for young jobseekers”, September 2012) which:

… reported that the estimated annual cost of effectively implementing the Youth Guarantee in the Eurozone would be 0.2 % of GDP36 or 0.45 % of government spending, which amounts to 21 billion euro

In other words, the European Commission pales into insignificance when one considers the problem.

I considered the ILO Report, in part, in this blog – ILO … ILF … IMF.

Further, the ECA found that despite the requests from the European Commission for Member States “to provide a cost estimate of the planned measures and the related sources of funding” for their Youth Guarantee initiatives, the responses were poor (in scope and quality) and “does not allow early identification by the Commission of possible shortfalls as envisaged”.

Further, the five Member States who formed the focus of the Audit Review failed to provide “information on the estimated implementation cost of the structural reforms required for the de- livery of an effective Youth Guarantee”.

Nine of the 28 Member states provided no cost information at all.

The ECA concluded that:

… it was therefore not possible for the Commission to assess the suitability of the funding source for the measures or to conclude on the overall feasibility and sustainability of the Youth Guaran- tee financial plans.

In terms of quality, the ECA noted that there was a plethora of documentation which outlined “non-binding qualitative minimum standards of good quality for traineeships and apprenticeships to prevent companies exploiting them as cheap sources of labour.”

But, they found that the reality of the implementation was starkly different.

They found that the European Commission had approved a program “submitted by Italy”, for example, which:

… would consider an offer of temporary employment (five to six months) to be “good-quality” even if the salary is below the monthly income poverty threshold in most parts of the country,

The ECA was more broadly critical of the program which I will leave you to catch up on if you are interested.

Conclusion

The lack of participation by the Member States that the ECA clearly found suggests that the program will not solve the youth unemployment problem.

The reasons for this lack of involvement at the Member State level are not disclosed.

Further, the tendency to offer poor quality – exploitive – opportunities in the small number of projects already proposed is deeply disturbing.

The lack of funding that the ECA finds is not surprising given that policy making in Europe is about austerity rather than solving the actual problems the continent faces.

The Audit results are not surprising. The policy making elites in the European Commission are caught up in a destructive austerity Groupthink that precludes them from making any realistic response to the problems at hand.

They could have created millions of inclusive jobs by now. But instead all they have created is entrenched mass unemployment and a lost generation of youth.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2015 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Bill,

Germany has managed (as usual) to officially (at least) reduce youth unemployment as shown in your graph – how have they achieved this?

Dear Bill

We keep hearing how bad the Japanese economic performance since 1990 has been. Funny that they have such a low youth unemployment rate and that it hasn’t increased since 2007. It turns out that a lot of the macroeconomic statistics for Japan can be explained by demographics. Between 1999 and 2014, American GDP grew by 33% and the Japanese one by 14%. However, the American population of working age (15 – 64) increased by 27 million in that period while the Japanese one decreased by 9 million. As a result, the Japanese GDP per person of working age went up 27% in Japan while it went up by 16% in the US.

If you take demographics into account, the Japanese economy has performed better that the American one since 1999. Of course, what matters is not GDP per person of working age but GDP per capita. If people between 15 and 64 become steadily more productive but their share of the population steadily falls, then GDP per capita doesn’t grow as fast as productivity, or may even decline.

Anyway, I got these figures from Pierre Fortin, the economics writer for the French-Canadian magazine L’actualité. Regards. James

Our politicians are telling us about the threat to future generations of having to pay back all our debts. What actually threatens future gnerations is that a huge proportion of them will not be in work and never will have been.

The various governments that won’t implement a jobs gaurantee could save even more money by abandoning the charade of mandatory schooling. Why bother paying for a kid to go all the way through to secondary education if upon leaving he is going to dig ditches (that is if he is lucky enough to get that job!)? Really if there are no jobs for the masses then there doesn’t need to be schooling for the masses. What to do with all these aimless, uneducated, unemployed masses? Well that is what those few lucky idiots digging ditches have a job for!

Willy, what you have said is so far off the mark that it can’t even be said to be wrong. A country of ignoramuses can’t contribute to a democracy. Education isn’t need for work per se, it is necessary for civic participation, among other things.

But perhaps you were being ironic.

James Schipper – Your comment illustrates,at least in part,the large part that increasing population plays in economic matters and it now never plays a positive part.

This is because we have passed the limits to growth.

By the way,GDP is not a satisfactory measure of the welfare and prospects of a nation.

Podargus, you are right about GDP and some economists are finally getting it. Bill talks about this, but also have a look at the following for an alternative approach: Stiglitz et al., A Call for Change: From the Crisis to a New Egalitarian Ideal for Europe, Progressive Economy, April 2014, and Torres et al., World of Work Report 2013: Repairing the Economic and Social Fabric, International Labour Organization, 2013. Both focus on job creation.

How long till the masses rise up and have a revolution?

Sadly I feel it may be a decade or two. More likely there will be war before that to solve the issue so much messier than required (major understatement!).

Humans can be so stupid.

Nigel:

Money, debts etc. are a construct of man and not a real constraint, whereas the earth and its resources which sustain life is. We are electing morons to represent us who arguably mirror the electorate for the most part.

There is no shortage of work to be done and no shortage of money to compensate people for that work.

It is one of the oddest of ironies, however, most of us cannot see it.

Wow, thats great stuff James. I’ll bring that into my argument portfolio going forward!

“We are electing morons to represent us who arguably mirror the electorate for the most part.”

Daniel D.

“Multivariate analysis indicates that economic elites and organized groups representing business interests have substantial independent impacts on U.S. government policy, while average citizens and mass-based interest groups have little or no independent influence. The results provide substantial support for theories of Economic-Elite Domination and for theories of Biased Pluralism, but not for theories of Majoritarian Electoral Democracy or Majoritarian Pluralism.”

from http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayAbstract?fromPage=online&aid=9354310

Gilens and Benjamin

The western electorates have had little influence on policy direction in the last 40 years.

Class war against democracy by western economic elites has led to worsening economic outcomes and declining productivity. This conclusion is supported by research conducted by the US government into the effectiveness of public sector spending. This topic is now a growing area of research but the damaging effects of a declining public sector have been understood empirically since the early 1980s.

http://marianamazzucato.com/the-entrepreneurial-state/

http://www.press.umich.edu/335760/beyond_sputnik